Home Truths

Sally Rooney’s family drama.

Sally Rooney’s Open Question

In Intermezzo, we get characters acting out their political commitments instead of just talking about them. But is their vision of domestic cooperation enough?

Sally Rooney has become known as a novelist of love, youth, and the combination thereof. Her characters come together as they come of age, in novels that combine romance with heady conversations on the disappointments and injustices of contemporary life. Rooney herself has jokingly implied that her primary subject could be reduced to “attractive young people in their twenties and thirties hanging around Dublin, doing no work, and thinking about sex.” But over the past five years, she has also quietly turned her attention to several themes that are less remarked on in discussions of her work: bereavement and brotherhood, and sometimes both.

Books in review

Intermezzo

Buy this bookFirst there were the Kearneys in her 2019 New Yorker story “Color and Light”: Aidan, a hotel worker, and Declan, his older brother by a year and seemingly well-connected, are mourning the loss of their mother after a long illness. Aidan imagines his grief as a sore throat, which “may get worse when you swallow, may be almost unbearably painful when you swallow, but that doesn’t mean that the pain is gone when you’re not swallowing.” Declan remains absent for much of the story, serving primarily as a link between Aidan and a screenwriter named Pauline, who refers to Declan as her “car friend,” since he can always be relied on for a lift. Ultimately, the brothers’ relationship appears to be something of a red herring; they share only two brief scenes in which their limited interactions revolve around the presence of Pauline.

A similar dynamic appears in Rooney’s 2021 novel Beautiful World, Where Are You. In it, Aidan becomes Felix, a taciturn warehouse worker; Pauline becomes Alice, a novelist whose meteoric rise mirrors Rooney’s own; and Declan becomes Damian, whose phone calls Felix assiduously avoids answering. As with the Kearneys, Felix and Damian’s mother has died and left behind a house that they have agreed to sell, although Felix doesn’t seem to want to, even though he needs the money, because “that’s me, can’t do things the easy way.” And, like Declan, Damian barely appears in the novel—just once, at a house party. The siblings’ relationship is a minor feature in a narrative that is primarily about the shifting relations among a group of friends and lovers.

Rooney also populates her latest novel, Intermezzo, with plenty of friends and lovers. But for the first time, her wounded and grieving brothers have escaped the margins of her narrative. Intermezzo’s action centers not just on a set of introspective, good-looking young people talking, flirting, and sleeping with each other, but on two siblings: Peter and Ivan Koubek, 32 and 22, whose father—a reserved Slovakian immigrant—has died just weeks before the novel’s opening after five years of cancer treatment. He, too, has left behind a house, this time in Kildare, 30 miles west of Dublin, where both of his sons now live. Having become “somehow suddenly head of a family which has at the same time ceased to exist,” Peter is acutely aware of the familial duties he has inherited. Yet holding what remains of the Koubeks together will be no easy feat. Part of the difficulty is that while he and his brother are linked by blood and the weight of their shared loss, the two have very little in common in terms of temperament, interests, or communication styles; they aren’t even technically members of the same generation. Figuring out how to coexist, perhaps even how to love each other, will be the primary challenge they face in Intermezzo. Their relationship is a microcosm of the novel’s interest in learning to live with difference—not just the kind that exists between individuals but also the warring factions that exist within each of them. And, of course, the most fundamental difference of all: that of life versus death.

The Koubek brothers’ basic incongruity is suggested from Intermezzo’s very first page, when Peter, remembering the ill-fitting suit Ivan wore to their father’s funeral, recalls the words of one of their aunts: “Brains and beauty.” Her observation was “about them both,” he thinks at first, before immediately correcting himself: “Or was it Ivan brains and Peter beauty.”

This is, crudely put, the cardinal difference between them. Ivan, a former child prodigy in chess, is cerebral, rational to a fault, and ill at ease in social situations. Peter, a debate champion turned human rights lawyer, is intelligent and cultured but at heart a sensualist. Guided by his appetites, he moves through the world with an instinctive kind of grace.

The brothers’ polarity is expressed formally, too. The sections devoted to Ivan’s perspective are narrated in a conventional close third-person, while those following Peter are composed of Joyce-inflected fragments, which gives them a feeling of immediacy. They are also more preoccupied with sensory detail, such as the feeling of sweat on skin: “Letting him touch with his fingertips her damp underarm. Chalky scent of deodorant only masking the lower savoury smell of perspiration.”

Inevitably, the friction generated by the brothers’ conflicting dispositions ignites an explosive argument. For much of Intermezzo’s nearly 500 pages, Ivan has Peter’s number blocked. Any hope of healing the breach between them rests on their capacity to find something productive in their tension—to become, if not exactly different, then less immovable.

In 2022, Rooney delivered the annual T.S. Eliot Lecture at the National Theatre of Ireland, in which she argued that since the interventions of Jane Austen, character in the Anglophone novel has been “staged purely in relationship to other characters,” as opposed to between an individual and the external challenges that they must overcome. Whether this analysis holds true across such a broad swath of literary history is open to debate, but it certainly applies to her own fiction. Rooney has long structured her novels around relationships and their capacity to remake us for the better. Conversation and sex are not just pastimes but engines of epiphany, and her characters are most pliable in these intimate moments. Indeed, Marianne’s conclusion at the end of Normal People could stand as a thesis statement for Rooney’s entire body of work: “People can really change one another.”

In Intermezzo, these agents of change are women, without whom the brothers would remain mostly static. The first of these is Margaret, whom Ivan meets while visiting a town in the countryside for a chess exhibition match in which he is paid to play 10 games simultaneously. Fourteen years older than him and recently separated from her husband, who has become a serious alcoholic, Margaret is convinced almost from the outset of their meeting that she and Ivan belong “somehow to the same camp.” Neither the age gap nor Ivan’s braces can counteract her elemental attraction. Despite the potential repercussions for Margaret, both personal and professional, she almost immediately sleeps with him, and this presumed one-night stand soon blossoms into a relationship.

In addition to his increased happiness and erotic gratification, Ivan’s relationship with Margaret produces other salutary effects. He has a newfound compassion for women, toward whom his primary feelings had once been confusion and resentment. More significantly, he senses a wholeness within himself that had previously eluded him. “It has always been Ivan’s philosophy…that the body is merely a sack of flesh and the brain an animating consciousness,” Rooney writes. But now, “on his walks around the city lately—after long arduous chess games in which his brain has played a role he has not entirely understood—it has occurred to him that perhaps the mind and body are after all one, together, a single being.”

Peter proves a tougher nut to crack. Though ostensibly more secure than Ivan—he’s the beauty, after all, and professionally successful by any standard—beneath his pleasing surface, he is emotionally disorganized and depressed, a state that Rooney conveys through muddled syntax that mirrors his troubled psyche: “Thoughts rattling and noisy almost always and then when quiet frighteningly unhappy. Mentally not right maybe. Never maybe was.”

One of the things for which Peter most often upbraids himself is his simultaneous attachment to two women, who between them replicate a version of the dynamic that exists between himself and Ivan. There is Sylvia, a brilliant professor of literature and former girlfriend of many years, who has been estranged from her body in a very literal fashion: She developed a severe chronic-pain condition after a car crash that makes it impossible for her to endure penetrative sex. Then there is Naomi, a 23-year-old college student, funny and streetwise, a creature of pleasure who has, when necessary, traded her desirability for cash by selling nude photos. Sylvia broke up with Peter after her accident, but they maintain a charged friendship. His relationship with Naomi, meanwhile, started as casual and at least partly transactional: Peter sometimes covers the costs of her prescriptions or buys her clothes. But lately it has taken on a more earnest dimension, “like a stage fight where it turns out the knives are real.”

Peter, who like many a Rooney character before him places a premium on the concept of normality, prefers to be in love with one person at a time. He also sees the two women in his life as representing mutually exclusive paths: “Maturity against youth. Yes, sobriety against decadence, intellect against appetite, he could go on.” This state of affairs is intolerable to him not because he is betraying either woman—they know about each other, even if Naomi doesn’t grasp the depth of his feeling for Sylvia—but because it’s symptomatic of his own internal inconsistencies: “the false true lover, the cynical idealist, the atheist at his prayers.” He is not interested in finding equilibrium through these two relationships; rather, he wants to achieve a purity that will allow him to make a final choice between them. He wants to feel once again “like a good person, even halfway good.”

It’s an attitude for which Peter is excoriated by Naomi, who calls out his fear of complication and disorder for the cowardice that it is. “You’re so fucking sick in the head you don’t even see what you’re doing to yourself,” she tells him. “Trying to put everyone in their little box. And if we would all just stay there, then there wouldn’t be any problems.” It will take Peter’s arriving at the point of a more serious emotional crisis for him to accept that the “conceptual collapse of one thing into another, all things into one,” is not something to fear but the only possible way for him to live.

The opposing forces animating Intermezzo are not only embodied through competing personalities. The Koubek brothers must also come to grips with how to carry on in the wake of everyone and everything they have already lost, knowing that they too will someday cease to exist.

From Ivan’s perspective, the death of his father has given him a certain freedom—from the days and weeks spent in the hospital, from the anxiety of waiting—which has allowed him to make “impulsive decisions” such as falling in love: “His life has been transformed, in an uncontrolled rush of energy and feeling.” On the other hand, he recognizes that while the event of his father’s death has definitively passed, “the loss remains, which can never be recuperated.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →For Peter, the grief becomes entwined with the quagmire that is his romantic life. “Disorder of sentiment,” he thinks at one point of his feelings for Naomi and Sylvia, a moment of self-censure that suddenly and inexplicably gives way to a memory of his father, who “would write out on lined paper the doctor’s instructions, spidery handwriting, names of medications.” This methodical image, with its air of resigned dignity, seems like a rebuke to his own disintegration.

Ivan’s growing affection for Margaret also becomes mixed up with his frustrated love for his father, which can no longer reach its intended object. But in his case, the conflation is less distressing than bittersweet. The night after he first tells Margaret that he loves her, and she returns the sentiment, Ivan is moved to tears while replaying the moment. The feeling it gives him is

Not even a feeling of unmixed happiness, but of happiness that was strongly and confusingly mixed with many other feelings. Sadness, missing his father, and a kind of shame somehow, because each passing day seemed to bring Ivan further away from him and the life they used to have together, a life that was increasingly receding into the past, into the realm of childhood and adolescence. The realisation that his adulthood, into which he was entering now so definitively, and which would last all the rest of his life, would have to be lived without his father. That he was becoming a person his father would never know.

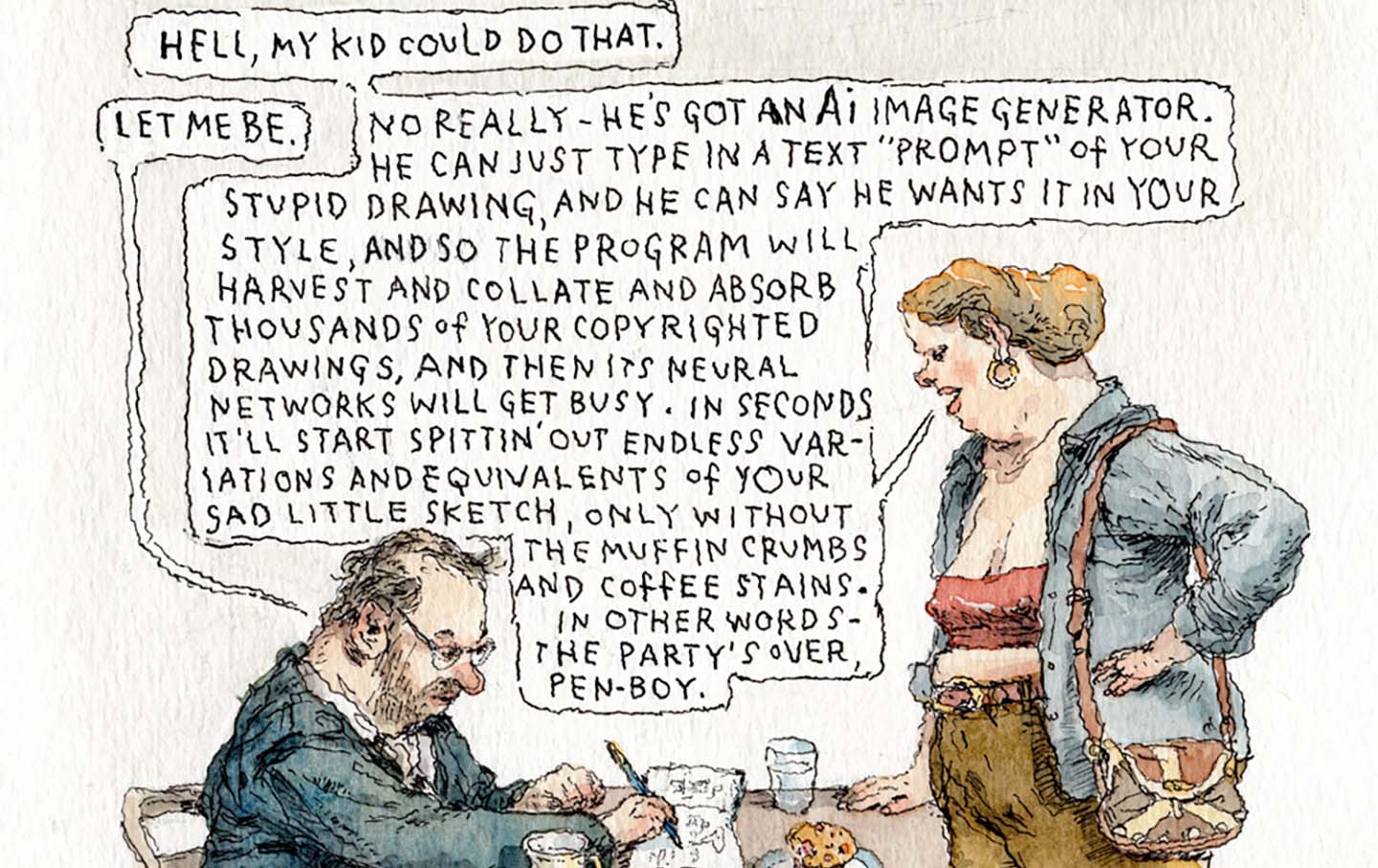

Love, grief, shame: These are not just Intermezzo’s thematic preoccupations but the substance of most of its talk. And as in any Rooney novel, there is a lot of talk. While in her previous work much of this talk was explicitly political—discussions about empire and feminism, the exploitation that undergirds Western convenience, and whether or not beauty died with the demise of the Soviet Union—in Intermezzo her characters are focused more narrowly on their own moral and emotional quandaries. Mostly, what everyone talks about is themselves and sometimes also each other. This is not to say that politics is not present in the novel, but that whatever political ideals these characters hold tend to be acted out rather than debated: Peter’s legal work consists mostly of advocating for workers’ rights; he and Sylvia belong to a tenants’ union; Margaret channels her belief in bringing avant-garde art to rural audiences through her job at the arts center; and Ivan has given up flying for environmental reasons.

This tendency toward action is in some ways refreshing: Rooney’s previous novels were often criticized for the way her characters spent almost all of their time hand-wringing over the gap between their passion for equality, justice, and redistributive economic policies and their comfortable bourgeois lives. In Intermezzo, this dilemma is mostly put to the side, and instead we get characters acting out their political commitments while struggling to make sense of their personal lives. Yet at the level of conversation, the inward turn of Rooney’s protagonists can at times feel claustrophobic, their intense focus on themselves and their lovers excessively recursive. Instead of spinning out into the world, Rooney’s characters end up trapped even more inside their own heads.

The politics that they do ruminate about are no longer tied to questions of world-historical matters, but instead to one’s intimate and familial relationships: What kind of families could we choose to make when our imaginations are not limited by convention? For Margaret, the connection she feels to Ivan prompts her to think that they are creating “a new relation…a way of being.” Falling in love with someone so outwardly unsuitable allows her to imagine “another kind of life, free of all the remorse and unhappiness she had accumulated before,” when her priorities were shaped by the perceptions of her mother and her small town. Does this new kind of life require the creation of a new world, too? Perhaps not. While it stretches Margaret’s understanding of the possible, the change exists mostly on the level of worldview.

Meanwhile, Peter’s affection for Sylvia and Naomi transforms him as well and opens him up to a new way of living. He accepts the shallowness of his hang-ups about non-monogamy and realizes that he can’t disavow his feelings for either woman without betraying a part of himself. Remarkably, Sylvia and Naomi agree, and the three of them resolve, as Peter euphemistically puts it, to remain in each other’s lives. While the arrangement could be interpreted as a crass division of emotional and sexual labor designed chiefly around Peter’s happiness, Rooney presents it as something more hopeful, too: a way of defining relationships to “meet the needs of the moment.” Peter even fantasizes that the relationships he has created might contain within them “the possibility, the ideal of another way of life”: one in which love isn’t finite or proprietary but endlessly renewable, capable of eroding social categories that help maintain an unjust status quo.

Peter’s utopia may be impossible to scale—a fantasy of bloodless revolution that begins from the inside out—but it does manage to resolve the contradictions of his own life. Yanked back from the abyss by the combined efforts of Sylvia and Naomi, he makes amends with Ivan and takes an immediate liking to Margaret, whom he had previously viewed from afar with skepticism and even derision, and Intermezzo closes with the more modest revolution that takes place in these five people’s lives. The final lines of the novel prompt us to picture them spending the holidays at the former Koubek house, ensconced in cozy domesticity: “clatter of saucepans, steam from the kettle.”

Intermezzo’s denouement, while focused more on interpersonal and private realms of change than on public ones, recalls a moment in Conversations With Friends when Frances and Bobbi wonder whether love could ever be anti-capitalist, insofar as it “challenges the axiom of selfishness which dictates the whole logic of inequality.” They resist coming to any determinations on the matter, as does the novel itself. But Intermezzo, jettisoning Frances and Bobbi’s more stringent Marxism, seems to find its own answer: Whether love can materially challenge the capitalist order is still an open question, but whether it can create a more equal society among friends and family is, at least in the novel, optimistically confirmed. Realizing this vision, paradoxically, clarifies its smallness: Peter, Ivan, Margaret, Naomi, and Sylvia may be rehearsing for a better world, but it is one that primarily exists at home. Embracing new forms of cooperative living is hardly a bad thing, yet in Intermezzo, the effect is ultimately quaint. After all, the image of this quintuple exchanging gifts by the fire wouldn’t look out of place on a Christmas card.