No Other Land and the Brutal Truth of Israel’s Occupation

“No Other Land” and the Brutal Truth of Israel’s Occupation

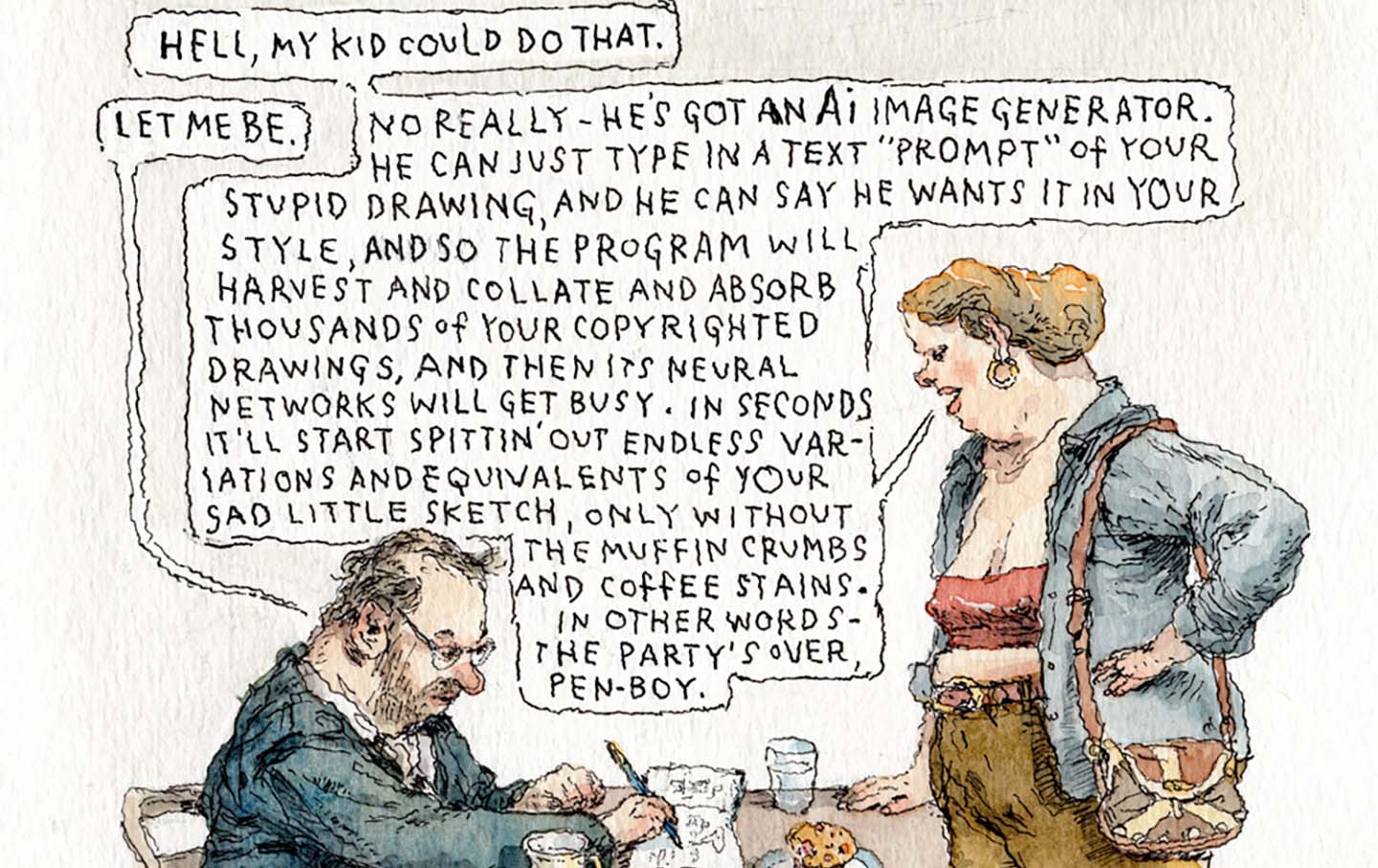

The unsparing documentary—one of the year’s most powerful films—has still not found a distributor in the US.

No Other Land follows Basel Adra, a young Palestinian man from Masafer Yatta, a collection of 20 villages in the West Bank, who began recording Israel’s destruction of homes in his community when he was 15. Adra worked alongside Yuval Abraham, an Israeli journalist, and the directors Hamdan Ballal and Rachel Szor to make the documentary.

The film showcases the banality of “service” in the occupation: The men and women of the Israeli army are shown milling about or growing apoplectic at Palestinian children, even as they commit war crimes in the West Bank. Israel’s script in the region is well-known and well-rehearsed: The army—which governs Palestinian life—declares an area of land closed to Palestinians in order to conduct live training exercises; then, settlers are invited to erect their encampments in the “military zone.” The whole show, which has resulted in the presence of more than 700,000 settlers in colonies across the West Bank, amounts to a countrywide grand larceny. Meanwhile, Israeli courts have been used to launder the proceeds—and the biggest fence is the one draped in legal robes.

In this case, a court took 22 years to whitewash the crime; the ruling, which favored the army, was delivered in 2022. Another fact on the ground—the immutable logic of Zionism. It’s all another reminder—about as subtle as a rusty nail in the brain—that the ethnic cleansing of Palestine never ended. The Nakba continues; No Other Land makes this very clear.

I struggled to watch No Other Land. Melancholy and outrage kept me from sitting still and focusing on the screen. I wanted to jump out of my skin, to be somewhere else and avoid the story altogether. But looking away is a privilege, one that is overwhelmed by the responsibility to bear witness and to share in the grief.

While most of the film’s footage was captured from 2019 to 2023—before the current genocide in Gaza—a handful of important scenes occur perhaps 10 or 15 years earlier. We see Basel’s father as a young man, offering encouragement to children on a field trip against their fear of Israeli soldiers. Basel himself appears as a boy, while his father explains that Palestinians are armed with sumud, or steadfastness, in the face of arch injustice.

At one point, Basel reflects on the fact that he’s now his father’s age in that earlier video. Thus we learn that his family’s struggle is the Palestinian struggle in microcosm: an intergenerational effort to build a life, to imagine a future that defeats or transcends Jewish supremacy in Palestine. For Basel’s family, and for so many others, the effort has been a futile one. The occupation grinds on, remorselessly and endlessly.

One of the most heartbreaking scenes in the film depicts the destruction of a school in Masafer Yatta, one that was built simply because it was needed. No explanation is given for its demolition, but we don’t need one either. The school is treated as an unpermitted structure by the occupation authorities—one of the tricks of the apartheid government. So it’s destroyed and the area is declared a military zone. Rinse and repeat.

In the scene, a phalanx of Israeli soldiers appears at the school, menacing and dangerous, and the small children are forced to evacuate through a window. Their trauma is thick enough to choke on, and you can’t help but contemplate their futures in a system that diminishes the sanctity of their lives.

Basel and his family are joined in their fight to preserve their homes by Yuval Abraham, the Jewish Israeli man who helped create the film. His presence serves as a reminder that there is power in solidarity. It falls to Yuval, fairly or unfairly, to show that some Israelis seek to opt out of the system of Jewish supremacy they were born into. The appearance of Gideon Levy—the longtime Haaretz reporter who has served for decades as a plaintive moral voice in Israel—achieves the same end.

Yet even solidarity is spoiled by occupation. In one moment, poignant for its resonance, a Palestinian villager jokes with Yuval that he may be a spy. Yuval, whose command of Arabic is very good, laughs the moment off. But in the occupation, where the military spies on Palestinian communications to exploit any vulnerability—one’s poverty or marginalized sexual identity, the need for education or medical supplies—it is hard not to look askance at every Israeli and wonder exactly what he’s there for. Where did he learn to speak Arabic so well? Because if Palestinians learn Hebrew as laborers in Israel or in Israeli prisons, Israelis learn Arabic in the Shabak, the domestic spy agency.

There are other asymmetries baked into the frame. On several occasions, Basel asks Yuval if he’s going home—we don’t know exactly where—a question that carries with it an accusation, the possibility of taking a night off. Apartheid means that Yuval can leave: He has a passport and a yellow license plate. He is a free man, standing in stark contrast to the bonded humans on-screen.

For viewers from high-income countries who spend 90 minutes viewing the lives of people at the margins in the West Bank, it’s easy to imagine what isn’t shown on the screen. That Yuval will drive home on well-paved roads, through neighborhoods with neatly arrayed streetlights that subdue the darkness. That when he, or someone like him, needs medical or dental care, he will be able to preserve his health in a sanitary clinic or hospital and find a way to keep the afflicted tooth or to replace it, at least.

Those facts—insidious, itching at the base of the viewer’s mind—are contrasted with the fate of a Palestinian man who appears in the film: Harun, who is shot by an Israeli soldier, becomes paralyzed below the shoulders, and ultimately dies of his wounds in a cave. (The destruction of his home preceded his murder.) The film shows his steady deterioration and his mother’s plea that he die to find peace—his own and, one suspects, hers too. We are reminded thus of the enormous wealth gap and the de-development of Palestine: The per capita GDP in Israel is $53,000; in the West Bank and Gaza, it stands at $3,000, or roughly 6 percent of the Israeli figure.

No Other Land is a documentary in the literal sense of the word: Basel and other activists are documenting their dispossession. I felt, as I watched this young Palestinian man angrily confront Israeli soldiers, that for him the camera is a weapon and a shield. But its inadequacy is naked and blatant. Basel films as Harun is shot by an Israeli soldier. He films as a settler shoots another man in the abdomen. An illustration of the hopelessness of the reality they confront occurs inadvertently when Harun’s mother laments her inability to build a room for her son to die in. She gives no thought, apparently, to bringing his murderer to justice. In Palestine, we learn, justice is both blind and impotent.

The film was shot almost entirely before the genocide in Gaza began, and it carries moments of tender naïveté. In one scene, Basel wonders about rallying support for his community in the US Congress, a statement that elicits bitterness more than anything else. An added irony here is that the film has so far struggled to find a distributor in the United States, leaving it an open question as to when stateside audiences will actually be able to watch it. But the reality of Palestinian dehumanization—the total subaltern status of a people—would in this case be illustrated not in Washington but in Berlin.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →No Other Land won accolades at the Berlin Film Festival in February. A German minister of state for culture—Claudia Roth—clapped when the filmmakers accepted their awards. She was later attacked for doing so and forced to clarify her intent: Her applause “was directed at the Jewish-Israeli journalist and filmmaker Yuval Abraham,” not Basel Adra, the Palestinian who stood alongside him.

Thus, with no apparent irony, a German politician illustrates the reality of apartheid: that it cleaves people from people, and hearts from minds, too.