An Absurdist Novel That Tries to Make Sense of the Ukraine War

Maria Reva’s Endling is at once a postmodern caper and an autobiographical work that explores how ordinary people navigate a catastrophe.

A child on a swing outside a residential building damaged by a missile in Kyiv, Ukraine, 2022.

(Pierre Crom / Getty Images)Ukrainians have lost countless things in the more than three-and-a-half years of brutal war with Russia. But few would claim that their sense of humor is among them. Stand-up comedy marches on in Ukraine, albeit in underground bunkers and with regular interruptions from air raid sirens. The comedians, most of whom now donate their earnings to the war effort, joke that they want payback from Russia for making their jobs harder: “Russia has stolen my absurdism,” said comedian Vasyl Baidak in a performance in Kyiv in October 2022. He urged that “joke reparations” be added to Ukraine’s list of demands when the war finally ends.

Books in review

Endling

Buy this bookWith her riotous debut novel Endling, the Ukrainian Canadian writer Maria Reva steeps her readers in this tragicomic sensibility (and reality). It’s an impressive high-wire act—one that blends the horror of the war with all the bleak and unintended absurdity it has produced in its wake. Much as in the case of the comedians, Russia did its best to steal Reva’s absurdism. Thrillingly for all of us, she did not let it.

Endling’s heroine is Yeva, a woman in her 30s who hails from Kharkiv but has spent the last few years living out of her mobile scientific lab, driving around Ukraine. Yeva is a prominent fixture of the “mail-order bride” industry (or “international dating,” as these companies now prefer to be known), which at one time raked in tens of millions of dollars every year in Ukraine.

Yeva and her cohort are essentially bait for men, typically from North America or Western Europe, who pay thousands of dollars to fly to Ukraine in search of love. Reva does a brilliant job of taking apart and scrutinizing every greasy cog of this industry: the brides “sold off alongside other women like a doorknob,” the matrons who run the show, the obligatory interpreters (“lubricants of courtship”). But she saves her funniest barbs for the men themselves and their bizarre fantasies of idealized femininity: “Behold! The phenomenon of the Ukraine Woman! Well groomed with the legs of an antelope and eyes of a feline.” Yeva is not much of a bride, given that she can barely conceal her boredom with her Western suitors and sometimes turns them off with anecdotes about cannibalistic bees.

That’s because, like most of the women on the tour, Yeva isn’t out to find love. Instead, she finds in these would-be suitors potential donors for her true passion—malacology, or the study of snails. Yeva is on a quest to save her beloved gastropods from extinction, driving around Ukraine in her self-funded lab to conduct one-woman evacuations, rescuing her tiny friends from collapsing ecosystems. Yeva knows her vocation verges on delusion, and she’s particularly gloomy about the state of the world: “None of it mattered anymore. Even Yeva was tired of Yeva.”

Nastia arrives to shake things up. Nastia, who is 18 (“and a half,” as she regularly reminds us), is the daughter of a notorious activist from Komod, a feminist group known for organizing topless protests against the mail-order bridal industry (clearly based on the real-life group Femen). A year earlier, Nastia’s activist mother disappeared for unknown reasons. Nastia is determined to get her back the best way a teenager knows how: by pissing her off.

First she poses as a prospective bride, entering the industry her mother spent her life trying to dismantle. But after a year goes by with no sign of her mother returning home, Nastia decides to up the ante: She will kidnap 100 Western suitors, holding up a mirror to the countless disappeared victims of bride trafficking around the world.

Nastia needs a getaway vehicle for the job, and she thinks Yeva’s mobile snail lab will do the trick. So she approaches Yeva outside a party. At first, Yeva dismisses the younger woman out of hand. She demands that Nastia submit a prospectus, a budget, and a formal proposal for her kidnapping attempt. “Why don’t you write an op-ed?” Yeva asks at one point, in a last-ditch effort to deter her.

But Nastia’s energy is infectious, reminding Yeva of an earlier, less burned-out version of herself. The two arrive at a compromise, as Yeva agrees to a pared-back version of the plan: They will kidnap 12 men.

This is clearly the novel that Reva started out to write before the war: an absurd caper through a much-maligned industry in what was then the relatively peaceful land of her birth. Her earlier book of short stories, also set in Ukraine, features similarly amusing high jinks involving the country’s Soviet-era bureaucracy and the Wild West capitalism that followed its collapse.

In the first 100 pages of Endling, only brief allusions are made to the troops amassing on the other side of Ukraine’s border. Yeva and Nastia’s kidnapping stunt was meant to take place just after Valentine’s Day in February 2022. But inevitably, the Russian invasion, which began on February 24, 2022, comes crashing through the fourth wall and into the text.

Reva pulls us back from her fictional bridal story in Ukraine to take us to Vancouver, the author’s adopted hometown, where she is sitting in her parents’ attic quietly panicking about her relatives left behind in Ukraine, but also (more guiltily) about what the hell to do with her half-written novel now that the country where it takes place has become a war zone.

This frequent intrusion of reality into the novel runs the risk of being taken as a postmodern gimmick, but buoyed by Reva’s ever-present humor, these glimpses of reality add an urgency and poignancy that vibrate throughout the second half of the book. Including the war likely started off as a practical and political choice, given the seismic changes that the conflict has brought to the life of every Ukrainian, including Reva’s own family. It would have been tone-deaf at best to complete such a book while ignoring the real events about to be unleashed on its subjects.

But the intrusion of reality also elevates Reva’s novel, transforming it into a moving exploration of the pain of creating art, particularly art based on the pain of others. What does it mean to write about a war raging thousands of miles away, even if you know and love the people living in that country? Does it matter if you blur the truth about the memories you have of your 86-year-old grandfather, who refuses to leave the frontline city of Kherson? Or is it essential to smooth the sharp edges, to tell those lies for the sake of a “truthier truth,” as Reva puts it—the sake of art?

Reva repeatedly points to the absurdity of being a “Ukrainian writer.” Tragedy, she suggests, can have a flattening effect. When people far away hear about Ukraine, or places like it, it is too easy to put them in a box: that of victimhood. Reva is absolutely alive to the devastation of the war, but she refuses to be flattened. Rather than cover up the messy seams undergirding her novel, Reva exposes them. She wants us to laugh at her and, in doing so, to see her as two things at once: the navel-gazing writer in her attic, fretting about her publishing deal, but also the concerned granddaughter of a man in danger.

Endling has many endings. The first, less than halfway through the novel, is the one Reva wishes for: Her grandfather in Ukraine will agree to evacuate from Kherson. In this version, “An iron sheet will slide across the horizon, will close Ukraine’s sky. Any missile that dares to pierce this formidable shield will boomerang back to its origin, serving as a lesson to all the other little men on thrones: never invade a sovereign country.”

After this decoy ending, Reva dutifully picks up her pen and treads on with her half-finished novel, its characters springing back to life. Yeva and Nastia, having successfully kidnapped the 12 men, now have no idea what to do with them. No reasonable media outlet will pay attention to such a petty heist amid the looming prospect of war.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →While the women are loading up the van, an accidental 13th member joins the group: Pasha, a hapless Ukrainian-born engineer from Canada who provides many of the essential plot twists (and humor) in the novel’s second half. Pasha has returned to his homeland in search of a bride (key qualifications: light enough for him to lift, a simple girl with a simple name). In truth, he has also come back in search of the yuppie dream that he has been denied in Vancouver (a sprawling house with a sundeck and plenty of rooms for guests).

Complicating matters, Yeva, after hearing about a rare sighting of a snail that she thought was almost extinct, has no choice but to drag Nastia and all 13 bachelors to Kherson, in southern Ukraine, where the war is in full swing.

Reva miraculously pulls off this bizarre twist, inflecting the horror of war with slapstick élan. In Kherson, we witness dismembered body parts, a staged humanitarian-aid operation enacted by the Russian “liberators,” and, quite incredibly, some truly poignant scenes of snail intercourse.

This is a novel about trying to rescue the things you love, and the futility, sometimes, of doing so. Yeva loves snails in part because they are so utterly hopeless at saving themselves. When an ecosystem is destroyed, birds can fly away, bears or deer can run. But snails stay in place: “It’s the snails that tell you which ravine to save, which patch of forest lies at the core of their own species alongside many others.”

One can feel the desperation in Reva’s writing, particularly as she repeatedly returns to the fate of her grandfather. He continues to live every day as he did before the war, making soup, drinking exactly one shot of vodka, turning on the computer for his weekly video call with his Canadian family, documenting their lives in countless photo albums and archives. The author fantasizes about mobilizing her characters to lure him out from behind the locked door of his home, but she knows as a writer of fiction that she is only capable of so much.

“If I get the details just right, my grandfather will leave Kherson,” she writes. “If I really focus, I can end the war.”

More from The Nation

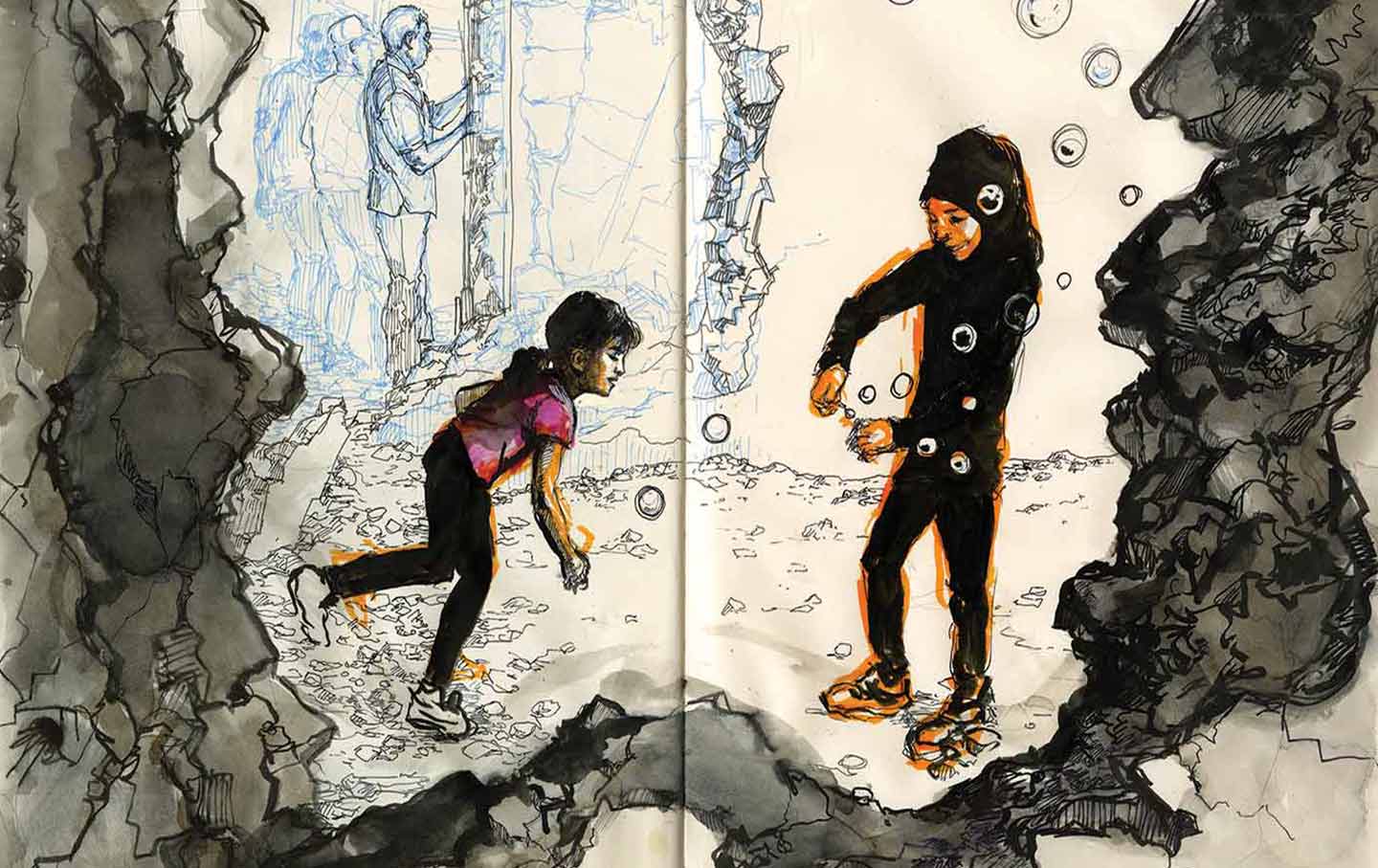

Molly Crabapple's Time Capsule of Resistance Molly Crabapple's Time Capsule of Resistance

A new set of note cards by the artist and writer documents scenes of protest in the 21st century.

The Exposure Therapy of “A Private Life” The Exposure Therapy of “A Private Life”

In her new film, Jodie Foster transforms into a therapist-detective.

Letters From the March 2026 Issue Letters From the March 2026 Issue

Basement books… Kate Wagner replies… Reading Pirandello (online only)… Gus O’Connor replies…

How to Build a Moon Garden When the News Is All Horror How to Build a Moon Garden When the News Is All Horror

The Riotous Worlds of Thomas Pynchon The Riotous Worlds of Thomas Pynchon

From “The Crying Lot of 49” to his latest noirs, the American novelist has always proceeded along a track strangely parallel to our own.