Jafar Panahi Will Not Be Stopped

Imprisoned and censored by his home country of Iran, the legendary director discusses his furtive filmmaking.

Jafar Panahi at the 2025 Toronto International Film Festival.

(Gareth Cattermole / Getty)It’s just after 1 am in Seattle as director Jafar Panahi and a posse of representatives from the local Iranian diaspora make their way to the next bar, the Space Needle looming nearby. Spirits are high—this bar crawl celebrates a rare opportunity for Panahi to tour with one of his films. In his home country, he is not just banned from showing his movies but barred from filmmaking entirely.

A legend of Iranian cinema, Panahi has been making internationally acclaimed films since the 1990s, but in 2010, his tendency to push sociopolitical buttons earned him a six-year prison sentence and a 20-year ban on making movies, writing screenplays, leaving Iran, or giving interviews. While the imprisonment was conditionally suspended, the various bans were upheld, so he continued to make films illegally. In 2022, he was sent to Iran’s infamous Evin Prison to serve out his original sentence, but was released after seven months after declaring a hunger strike. In 2023 his travel ban was lifted, and he was permitted to leave the country for the first time in 14 years. He’s resided in France ever since, allowing him to tour his latest film in the United States.

It Was Just an Accident—filmed stealthily in Iran—follows a group of former political prisoners who kidnap a man they believe to be their torturer from the state security forces with the intention of exacting revenge. But as events progress, their desire for street justice is complicated by questions of identity and morality. The film received the Palme d’Or at Cannes and is a likely competitor for Best International Feature at the Oscars (though, as a French entry, it has never been shown publicly in Iran).

In Seattle, the second stop along his US tour, Panahi received a warm reception from local fans. As the night pushed on, there were cocktails flavored with saffron, songs sung in Farsi, and a general atmosphere of jouissance that raged until closing time. The following day (and only somewhat worse for wear from the late night out), I spoke with Panahi about the film, the struggles of working under censorship, and the profound impact of Iran’s Woman, Life, Freedom protest movement.

—Nick Hilden

Nick Hilden: You’re banned from making movies in Iran, so many of your movies have been made underground, including your latest. How does that affect your production process?

Jafar Panahi: It certainly has an impact because production doesn’t follow the normal procedure. You have a smaller team and limited equipment. But in the end, you shouldn’t let it affect the quality of the work.

NH: You and your friend Mohammad Rasoulof are considered pioneers in Iran’s underground filmmaking scene. How do you think your work has impacted the younger generation of filmmakers in Iran?

JP: When they sentenced me to a 20-year ban, I had to find a way to work and make films. If we couldn’t find a way, despair would set in everywhere, especially among young people. And when we did, it gave them hope. In fact, many of the good films in Iranian cinema today are made like this. They don’t have any other option. Either they have to bow to censorship, or if they have to circumvent censorship—it’s the only way.

NH: With your latest film you confront the government more directly than with many of your previous movies. Was that intentional?

JP: I don’t know, I just made the film I wanted to make. I remember being told exactly the same things when I wanted to make The Circle [2000]. Even my friends told me not to do it. They’ll hurt you in ways you can’t imagine, they warned me. But I could not listen to that. I had to make my own film. And whatever the cost, I had to pay it.

NH: It Was Just an Accident deals with deadly serious themes but is also very funny. Where did that humor come from?

JP: Some of the humor happens unconsciously, and you don’t know that you’re going to make the audience laugh. And some of it is intentional. In this film, I wanted the audience to follow more comfortably up until the last 20 minutes and then leave them in absolute silence and take their breath away, to make them sit on the edge of their seats, completely glued to the screen. If I had not created this dichotomy, that ending wouldn’t have the meaning it did. Not that it would be meaningless, but it would not have the same impact. This way, when you leave the theater, you’re still thinking about the film.

NH: There has been much discussion about the film’s ambiguous ending. Why do you think that is?

JP: Because it makes the audience ponder the future. Is this circle of violence going to continue, or will things change? And this is the question we follow throughout the film. For instance, the main character, Vahid, has done something impulsive by kidnapping his torturer and is now in a situation where he doesn’t know what to do. He, too, questions his decision. But he knew from the start that this was the wrong path to go down. That’s why he went to Salar’s for help—because Salar could see a few steps ahead. Salar didn’t believe there was any need for revenge because the government had already dug its own grave, and they don’t have to be its gravediggers.

NH: So many directors and artists have been imprisoned in Iran. Why do you think some governments are so threatened by art?

JP: They’re threatened by everything! Anything that is against them or not in line with their agenda, they’re afraid of. So they rush to repress it. Even when you don’t follow their dress code. We still remember the first decade after the Revolution when they’d stop men in the street for wearing short sleeves and paint their arms. They were even threatened by how people dressed.

What matters is how the people react. People always push back. The government’s biggest battle line was compulsory hijab for women, and they lost that battle during the Woman, Life, Freedom movement.

NH: Do you think Woman, Life, Freedom had an impact?

JP: It has had a huge impact. The history of the Islamic Republic is now divided into before and after this movement. Most importantly, it made people make up their minds about the government. We saw this impact in the presidential elections following Women, Life, Freedom. Until then, the official rate of voter participation announced by the regime was never under 60 percent. But this time, they said it was 40 percent. And you can’t even trust that number.

NH: While watching This Is Not a Film [2001], which documents the moment you learn of your prison sentence and ban, I was struck by the art student discussing his struggles to find work. What is the situation for young people in Iran right now?

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →JP: The problems remain the same—the same extreme censorship that they want to increase every day. Perhaps you could ask, what is different now? The difference is that before, people did not have options, and now they do. Efforts were made but they would not get anywhere because things were so difficult. Now, those efforts are so abundant that the government—the regime—has lost control.

NH: Do you think change will come to Iran?

JP: There’s always hope.

NH: Authoritarianism is thriving around the world. What do you think people should learn from your work?

JP: They should learn from history, not from my films. We already had the Middle Ages in Europe, and people should have learned from it. In this day and age, you see that the same thing is happening in my country. If we learned from history, this would not be happening. And looking at all the dangers on the rise today, the world could learn from what happened in Iran 50 years ago. Unfortunately, the same cycle keeps repeating.

NH: Do you have any advice for young artists facing censorship?

JP: Just try to be themselves. That’s how they can find the way.

More from The Nation

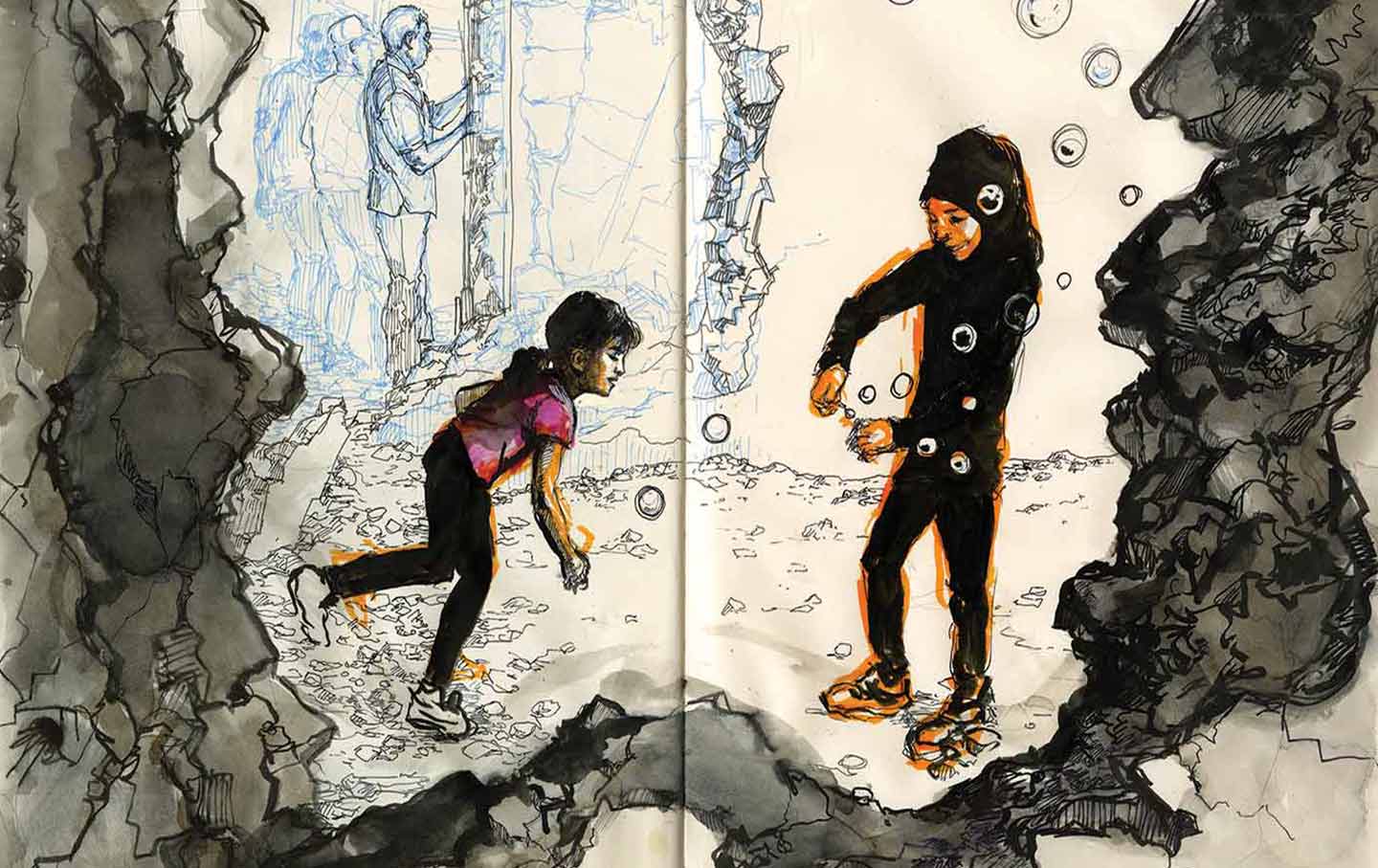

Molly Crabapple's Time Capsule of Resistance Molly Crabapple's Time Capsule of Resistance

A new set of note cards by the artist and writer documents scenes of protest in the 21st century.

The Exposure Therapy of “A Private Life” The Exposure Therapy of “A Private Life”

In her new film, Jodie Foster transforms into a therapist-detective.

Letters From the March 2026 Issue Letters From the March 2026 Issue

Basement books… Kate Wagner replies… Reading Pirandello (online only)… Gus O’Connor replies…

How to Build a Moon Garden When the News Is All Horror How to Build a Moon Garden When the News Is All Horror

The Riotous Worlds of Thomas Pynchon The Riotous Worlds of Thomas Pynchon

From “The Crying Lot of 49” to his latest noirs, the American novelist has always proceeded along a track strangely parallel to our own.