Barbara Pym’s Archaic England

In the novelist’s work, she mocks English culture’s nostalgia, revealing what lies beneath the country’s obsession with its heritage.

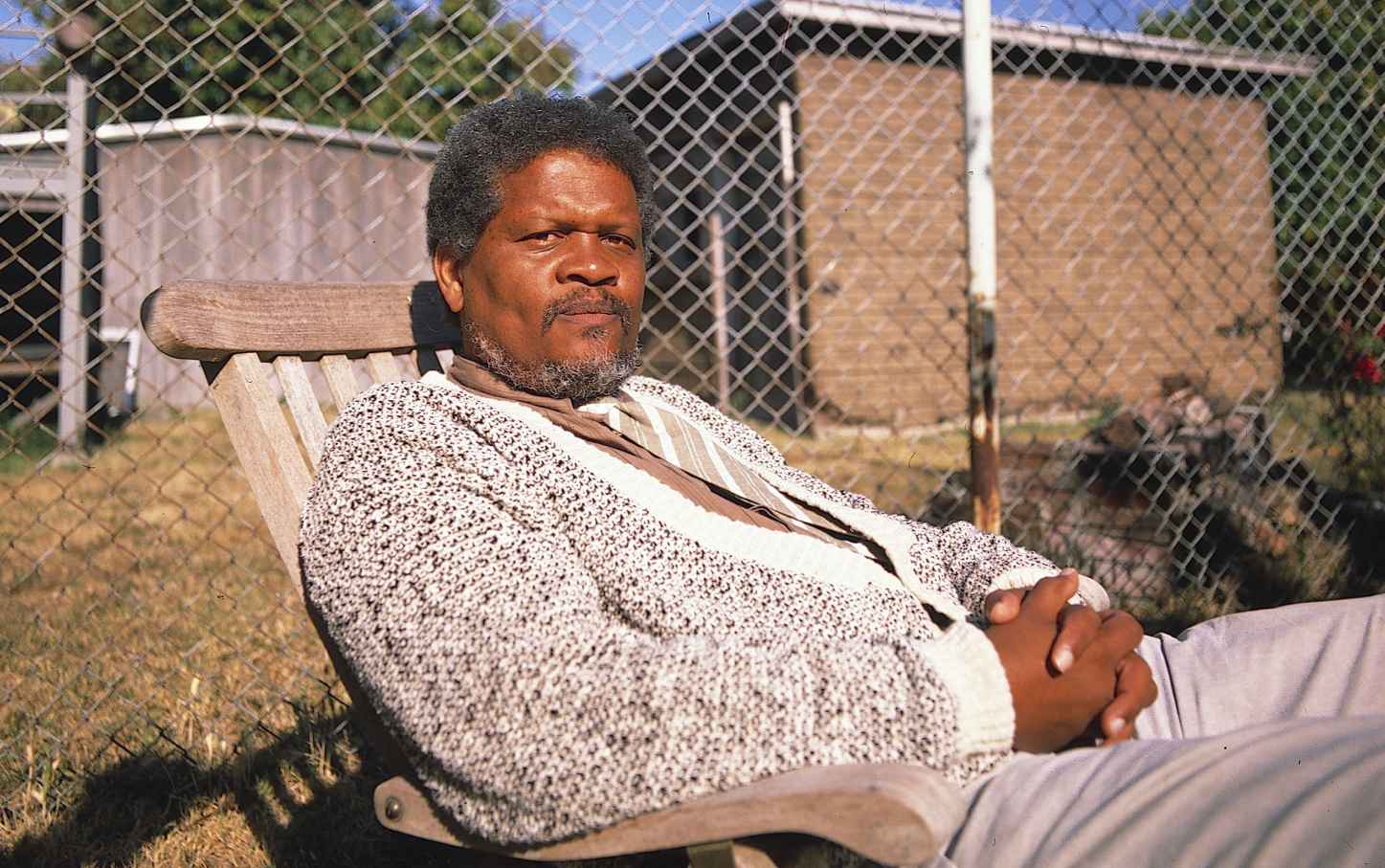

A World War II-themed party held by the residents of Rose Mount, Birkby, 1986.

(Staff / Mirrorpix / Getty Images)Within a year after Barbara Pym published her penultimate novel, The Sweet Dove Died, Margaret Thatcher would assume office as prime minister of the United Kingdom. In retrospect, these two events seem not unrelated. The 1978 novel marks a shift in the British writer’s career; published shortly after her return to print after a 15-year hiatus, The Sweet Dove Died ditches the comic tone of Pym’s earlier work for a set of themes that dominated her final novels: nostalgia, festering traditionalism, the feeling of outmodedness—concerns, in other words, gathered from her measured observation of a society on whose discontents Thatcher would soon capitalize.

Books in review

The Sweet Dove Died

Buy this bookThatcher rose to power on the back of a campaign to Make Britain Great Again—a promise to reverse the previous two decades of austerity, imperial contraction, and stagnating modernization. By 1979, the country was undeniably in decline—not just materially but on a more ineffable level, too. Divested of the unifying effect of global superpower status, the increasingly dis-United Kingdom’s common identity was now an open, and anxious, question. What would ensure the shared future of the nation? For Thatcher and her ilk, the answer (at least rhetorically) lay in conjuring an ideal imperial past and the fantasies of Merrie England that went with it: the Crown, the Empire, green pastures and trout runs, the 12th of August, upstairs and downstairs, overseas plantations, and Gloucester cheese. With one hand, Thatcher’s government rolled out staunchly anti-traditional monetarist policies; with the other, it stoked a reactionary fantasy of once and future greatness. If Thatcher’s neoliberal solutions—privatization, deregulation, reduced public spending—helped spur a modest economic recovery, their more memorable consequence was to gut the social and built landscape of the UK. Slashed pensions, political polarization, and crumbling infrastructure were the hallmarks of an administration whose disastrous attempt at warmongering in the Falkland Islands was rivaled only by its attrition of trade unions at home.

If the economic well-being of the British citizen could not be recovered, at least some distracting totems from days of yore could be. In 1980, months of debate over the preservation of historic properties led to the National Heritage Act, which, as Lords Mawbry and Stourton then explained it to the House of Lords, was “a memorial to everything in the past always”—insofar as those things were landed estates. Heritage was a cottage industry, too: This moment saw the ascendancy of the period drama, substantiated in a spate of Merchant Ivory films and ITV’s hugely successful Brideshead Revisited adaptation. A British Rail promotion advertised a limited run of “historical” train carriages with the slogan, “In the high speed world of today it’s nice to have a quick look back.”

These kinds of sentiments would almost certainly appeal to Leonora Eyre, the nostalgia-clotted heroine of Pym’s The Sweet Dove Died. For Leonora, an inveterate collector of Victorian memorabilia, history and consumption seem to go hand in hand. The sight of an enamel paperweight is enough to send her into raptures about how one wishes “to have lived in those days.”

As with Pym’s other novels, The Sweet Dove Died renders with wry humor the foibles and contradictions of a culture of manners—the art of the polite insult, the ludicrous arbitrariness of custom. Unlike Pym’s early works, however, The Sweet Dove Died raises the suspicion that the mores of British polite society might, after all, be neither charming nor well-meaning.

It is in this novel that Pym’s social comedy bends hardest toward social critique. Leonora acts as an avatar for the incipient politics of heritage: “an archaic figure trapped in Britain’s past successes,” as Perry Anderson once described the country’s postwar society. While it’s never been the most popular of Pym’s works, The Sweet Dove Died is the most searching: It captures Pym’s ambivalent reflections on a cultural landscape that she both profited from and yet clearly saw through.

Between 1950 and 1961, Pym published six novels, all alike in their subject matter; the characteristically quaint Pym novel, as Michael Gorra once wrote, “takes place across a middle-class tea table.” Her subjects were literally parochial: the men and women (but mostly women) of white, High Church Anglican communities in provincial Southern England. Of her 11 published novels, eight feature protagonists we might call spinsters; they are often engaged, or soon to be, by novel’s end, but only three are married when we meet them. Pym’s women are employed in vague, bookish professions that, if not entirely remunerative, allow them ample time to pursue extracurriculars—Jell-O molds, parish luncheons. Tea, of course. They live in humdrum corners of postwar London, or leafy suburban villages just beyond it, where they fall into relationships with curates, vicars, and the occasional civil servant. “Mild, kindly looks and spectacles” are what Pym’s characters expect from love—and what Pym’s readers love to expect in her work.

While Pym’s themes across the first half of her career were remarkably consistent, critical favor proved less so. Her would-be seventh novel, An Unsuitable Attachment, was dismissed by her publisher in 1963 as being insufficiently contemporary—the tea parties now no longer quaint but simply out-of-date—after which she remained unpublished for 14 years. Then both Philip Larkin and Lord David Cecil heralded Pym as the “most underrated writer” of the century in a 1977 article for the Times Literary Supplement, bringing to her works widespread critical and popular acclaim. She earned a nomination for the Booker Prize and published three more novels—The Sweet Dove Died among them—before her death in 1980. Pym, one might argue, was both the beneficiary and the unwitting conscript of the new culture of nostalgia.

If Pym’s early characters are objects of nostalgia, they aren’t necessarily guilty of it—perhaps because they’re so firmly of their time. The same can’t be said of Leonora, whose Victorian fantasies and Edwardian attitudes are increasingly at odds with the present: Now “everyone [is] so young, the girls appallingly badly dressed, all talking too loudly in order to make themselves heard above the background of pop music.” She yearns for a time when her hair still had its color, when “servants were still humble and devoted.”

In the first chapter, Leonora has lunch with Humphrey Boyce, an antiques dealer, and James, his nephew and trainee. The group has only just met, the Boyces having saved Leonora from fainting at a rare books auction. Humphrey is attracted to her; James is too, “in the way that a young man might sometimes be to a woman old enough to be his mother.” Leonora recognizes Humphrey’s attention but has her sights on the more naïve, manipulable James. This meeting sets off a mess of entanglements: Leonora balances Humphrey’s interest in her with her own attempts to keep hold of James as he’s courted first by a graduate student named Phoebe and later by a guileful American, Ned.

Much of the novel takes place within the home. As with her relationships, Leonora’s flat is arranged meticulously—aquamarine paper tissues on the bureau, a Victorian flower book open in the foyer. “Somehow I feel they’re me,” she says. This comparison is more apt than Leonora might like to admit, for Pym wants us to see her as an artifact herself: patinated surfaces disguising a hollow interior. At different moments, Leonora is described as “a piece of Meissen without flaw”; “hardly human, like a sort of fossil”; and “some old fragile object.” Sometimes the comparisons are overwrought, but they drive home the point that Leonora is precious about her age. Her favorite mirror, an antique, makes her look “fascinating and ageless.” There’s a flaw in the glass that creates this effect, but it’s permissible because it massages over her perceived flaws—“the lines where there had been none before.” The analogy here, obvious to everyone but Leonora herself, pertains to the incommensurability of the ideal image and reality, maybe too with the way the ills of the past reproduce themselves in the present. Leonora’s way of seeing the world—or rather, her way of seeing what she wants to and willfully ignoring the rest—is, quite literally, distorted.

Like any good conservative, Leonora defines her life in the negative: as a reaction against. Frozen dinners, corduroy, the “cosiness of women friends,” fluorescent lighting—these are some of the things she condemns. One suspects that the characters who populate Pym’s other works would earn from Leonora the accusation of being “hopelessly middle class.” She finds persons with disabilities “too upsetting,” the elderly both “boring and physically repellent”—though Leonora herself, Pym frequently reminds us, is approaching the autumn of her own life.

The trick of Pym’s deft, multifocal narration is to expose Leonora’s perspective as ridiculous. In one early chapter, she and James go for a predinner stroll. The garden they choose for this occasion evokes for Leonora fantastical visions of “some giardino or jardin—perhaps the Estufa Fria in Lisbon.” James is more clear-eyed on the matter: “He would have preferred to sink into a chair with a drink at his elbow rather than traipse round the depressing park with its formal flowerbeds and evil-faced statue—a sort of debased Peter Pan—at one end and the dusty grass and trees at the other.” The typical attention to detail here and Pym’s strong sense of humor, barely contained, are inseparable.

It’s due to a “streak of perverseness,” Humphrey thinks, that Leonora prefers the attentions of James to his own. But if it’s perversity, it’s not the sexual sort, or not the kind involving actual sex. Reflecting on her romantic past, Leonora wonders, “had there ever really been passion, or even emotion? One or two tearful scenes in bed—for she had never enjoyed that kind of thing—and now it was such a relief that one didn’t have to worry anymore.”

No, Leonora’s real predilection is for control. “All one’s relationships have to be perfect of their kind,” she says. Predictably few are capable of meeting this standard, though Leonora works hard to ensure that those of her circle who aren’t up to snuff are at least in her obeisance. When James begins sleeping with Phoebe, Leonora furtively moves him into her spare apartment in order to better keep an eye on him. The casualty of this arrangement is less Phoebe herself than Leonora’s now-former tenant, the elderly Mrs. Fox, whose senility and “dingy Jacobean curtains” threaten to disrupt the façade of Leonora’s home life. “One will simply have to get rid of her.”

Though Leonora is able to successfully dispense with Phoebe, she finds a worthy rival for James’s affections in Ned, whose glittering personality “mak[es] Leonora seem no more than an aging overdressed woman.” Nonetheless, after Ned moves on, James crawls back to Leonora for comfort. “People do change,” she tells him—“one sees it all the time.” James, ever the font of wisdom, replies: “But not us, Leonora.” This seems precisely the problem.

Heritage discourse promises a frictionless engagement with “the past” without the baggage of history. Yet The Sweet Dove Died dramatizes the ways in which the rosy world of British heritage, with its country houses and social graces, cannot be abstracted from the material relations of exploitation that made this way of life available in the first place. Jed Esty has written that the feeling of decline often involves not only a politics of nostalgic nationalism but a “cultural attachment to obsolete modes of production”—the “golden era” of postwar manufacturing, in the case of the United States, and of imperial expropriation and slavery, in the British context. Pym is not shy about making this connection. Leonora’s fondness for the cultural relics of Victorian England bleeds quickly into a straightforward fantasy of empire, as when she imagines herself “as a beauty of the Deep South being handed from her carriage, or as a white settler.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Historical reality often has little to do with the romantic visions of the past we conjure. This is a distinction built into the architecture of Pym’s fiction. As much as the world she renders is beloved for its rosy quaintness, her novels themselves are scarcely nostalgic for a time gone by. Modernity’s creep reveals itself in the mumblings of characters about austerity, the jeans-wearing readership of The New Statesman, and the increasing popularity of Heinz beans. The world Pym’s characters remember is on its way out, and for the most part they meet the future with ambivalence, observing curiously its loosening class hierarchies and evolving fashions. By her final novel, A Few Green Leaves (1980), the local manor seat has been sold off to an absentee businessman. Of this change, one character remarks, “all that patronage and paternalism or whatever you like to call it has been swept away, and a good thing too.” Doe-eyed traditionalists may run amok, but they’re often the object of Pym’s satire—none more than Leonora.

Still, it’s clear that, for many, the pleasure of reading Pym lies in the fantasy her novels seem to inspire. In 2008, Alida Becker wrote, “If I want literary diversion come September, I guess I’ll have to escape into the fiction of the past. At the moment, I’m leaning toward the acerbic and resolutely small-scale…. If I’m feeling kindlier, a Barbara Pym or two.” Another critic described her fiction as “an escape to a little world of England.” Like the country B&B, Pym’s novels offer the shallow reader a chance to visit the artifacts of the recent past.

These sentiments were just as present in 1979. Philip Larkin championed her fiction for its focus on what he called “ordinary sane people doing ordinary sane things…[in] the tradition of Jane Austen and Trollope.” Larkin qualified this statement later by writing that “not everyone yearns to read about S[outh] Africa or Negro homosexuals.”

Nostalgia, Pym knew, devolves quickly into nativism. This is not to exonerate Pym on the virtue of her awareness of cultural politics—an awareness that did not preclude her close collaboration with Larkin. At the same time, in her writing, her commitment is to the keen observation of social phenomena—at first, the homespun rituals of a fading culture, and later, the reactionary politics taking shape in response to that loss. For all its light-heartedness, The Sweet Dove Died’s greatest effect is less comic than horrific, achieved in the moments when Leonora’s fantasy of Victorian culture gives way to the material relations always underlying it.

It’s not difficult to imagine the reproof that Humphrey levels at Leonora for these reveries being directed at some of Pym’s critics and readers, too. “My dear Leonora,” he cautions, “you’d have found it most disagreeable, you have this romantic view of the past—and of the present too.” Leonora promptly returns to her crème de menthe.

Your support makes stories like this possible

From Minneapolis to Venezuela, from Gaza to Washington, DC, this is a time of staggering chaos, cruelty, and violence.

Unlike other publications that parrot the views of authoritarians, billionaires, and corporations, The Nation publishes stories that hold the powerful to account and center the communities too often denied a voice in the national media—stories like the one you’ve just read.

Each day, our journalism cuts through lies and distortions, contextualizes the developments reshaping politics around the globe, and advances progressive ideas that oxygenate our movements and instigate change in the halls of power.

This independent journalism is only possible with the support of our readers. If you want to see more urgent coverage like this, please donate to The Nation today.

More from The Nation

Why We’re Still Fighting Over Elgin’s Marbles Why We’re Still Fighting Over Elgin’s Marbles

In A.E. Stallings’s Frieze Frame, the poet retells the many conflicts, political and cultural, the ransacked portion of the Parthenon has inspired.

Is it Too Late to Save Hollywood? Is it Too Late to Save Hollywood?

A conversation with A.S. Hamrah about the dispiriting state of the movie business in the post-Covid era.

The Melania in “Melania” Likes Her Gilded Cage Just Fine The Melania in “Melania” Likes Her Gilded Cage Just Fine

The $45 million advertorial abounds in unintended ironies.

Nobody Knows “The Bluest Eye” Nobody Knows “The Bluest Eye”

Toni Morrison’s debut novel might be her most misunderstood.

Melania at the Multiplex Melania at the Multiplex

Packaging a $75 million bribe from Jeff Bezos as a vapid, content-challenged biopic.

Ishmael Reed on His Diverse Inspirations Ishmael Reed on His Diverse Inspirations

The origins of the Before Columbus Foundation.