Why We Keep Reading All Quiet on the Western Front

Why We Keep Reading “All Quiet on the Western Front”

A new translation vividly renders the sadly evergreen influence of the Erich Maria Remarque’s World War I novel.

German soldiers, 1916.

(Hulton Archive / Getty Images)

When Germany declared war on Russia in August 1914, Erich Maria Remarque was 16 years old. Growing up in Osnabrueck, near the Dutch border, he’d harbored literary aspirations. But he was training to become a teacher when he was drafted to serve, in November 1916. Eight months later, a British grenade exploded near Remarque’s position in the Third Battle of Ypres, wounding him seriously. Though he would qualify for active duty again, it was not until November 7, 1918, four days before the Great War ended.

Books in review

All Quiet on the Western Front

Buy this bookIn the years that followed, Remarque moved through a succession of jobs: teacher, salesman, engraver, church organist, magazine editor in Hanover and Berlin. In 1920, he published a novel he’d begun as a teen, The Dream Room. Written in an aestheticist key (an artist character is called, unironically, a “priest of beauty”), the book was brought out by a tiny outfit, Die Schoenheit Verlag (Beauty Press), whose motto was: “Light and Love in Human Existence. Youth Through Nudism.” This wasn’t necessarily a fringe position in Weimar culture, but Remarque soon soured on his debut. He would disavow The Dream Room and even try to buy back the few copies that had been sold. In the mid-1920s, he began another novel, The Station on the Horizon, though it wouldn’t come out in book form until the late 1990s, a quarter-century after his death. So it was as a mostly unproven author that Remarque shopped around All Quiet on the Western Front, which he had written during an intensive six-week stretch in 1928. The first publishing house he approached passed on it. This was the prestigious Fischer Verlag, which published (and still publishes) Thomas Mann’s works. But Remarque’s next try met with success: The Ullstein Verlag initially serialized the novel in a newspaper it owned, Die Vossische Zeitung; the book in full appeared in January 1929.

All Quiet on the Western Front turned out to be a sensation when it was serialized and also once it was published as a book. Over 20 million copies have since been sold worldwide, with translations in more than 50 languages. Long a staple of high school curricula, the novel earned Remarque, who seemed genuinely stunned by its reception, two Nobel Prize nominations in 1931—one for literature and the other for the peace prize. The novel’s three major film adaptations (1931, 1979, and 2022) all won major awards (the 1931 and 2022 films received Oscars, the 1979 adaptation a Golden Globe). And from the moment of its release through the present day, reviewers have celebrated All Quiet on the Western Front for the “unsurpassed…vividness” and “reality” of its depictions of trench warfare. Those are the terms that Louis Kronenberger used in his 1929 appraisal for The New York Times.

Writing in The Saturday Evening Review, Christopher Morley, another early champion, put forth similar claims: “It is, to me, the greatest book about the war that I have seen; greatest by virtue of its blasting simplicity…. The quiet honesty of its tone, its complete human candor, the fine vulgarity of its plain truth (plainly and beautifully translated), make it supreme.” Dissenting voices also made themselves heard: All Quiet on the Western Front was burned and banned in Germany during the Third Reich. What offended Nazi officials was the perception that Remarque’s novel carried an unpatriotic message, one at odds with cherished accounts of German sacrifice and bravery on the battlefield. The outrage led the author to flee to Switzerland in 1931 and, in 1939, to the United States, where he kept writing novels and took advantage of the social opportunities his celebrity afforded him, spending time with Charlie Chaplin, Marlene Dietrich, and F. Scott Fitzgerald, who adapted one of those novels for a screenplay.

If All Quiet on the Western Front has been both praised and attacked as an anti-war book, it has also long been charged with “romanticizing” the war, due in part to how much it dwells on soldierly bonding in the trenches. Moreover, it has been seen as being “anti-war” in a vacuously apolitical way, or without reckoning with the forces that drove German militarism. (With Remarque’s assistance, the Ullstein Verlag removed some parts from the novel that dealt critically with Kaiser Wilhelm II and the outlook of the German officers.) Then there’s the charge that, despite its virtues, the novel fails to rise to the level of a literary masterpiece. For all his enthusiasm, Kronenberg ended his Times review by opining: “It is not a great book; it has not the depth, the spiritual insight, the magnitude of interests which make up a great book. But as a picture, a document, an autobiography of a bewildered young mind, its reality cannot be questioned.” Not surprisingly, some of Remarque’s contemporaries expressed their reservations in less decorous language. The Viennese critic Karl Kraus was a natural antagonist, having written a more innovative, much less widely read account of the war (The Last Days of Mankind, published in 1919). Kraus played that role with gusto, decrying all “the propaganda for Quark and Remarque.” (The German word Quark means “sour cream,” and also “nonsense.”)

In the preface to his new English translation of All Quiet on the Western Front, Kurt Beals makes his own case for the literary value of the text. Proceeding in measured tones, he brings up the claim that Remarque’s book is “the greatest war novel of all time” but doesn’t directly endorse it. Instead, Beals suggests that given the novel’s enormous influence (he notes its impact on Joseph Heller, the author of another widely heralded anti-war novel, Catch-22), it must be doing something right, and he tries to break down what that something is.

Beals puts particular stress on the idea that All Quiet on the Western Front possesses “a powerful sense of immediacy,” which, in his view, derives to a large extent from two features. The first is its “unusually terse,” “almost telegraphic” prose; the second is the correspondingly “blunt” perspective of its narrator, Paul Bäumer. Remarque keeps Bäumer’s reflections and descriptions clipped, even when he’s talking about such horrors as the body of a decapitated man taking a few steps before falling to the ground.

Both features figure prominently in Beals’s discussion of what he hoped to achieve in retranslating the book. According to him, A.W. Wheen’s original English translation (1929), which is still the go-to one, has its merits, starting with its imaginative rendering of the title: “Im Westen Nichts Neues,” a phrase that was broadcast over the radio in Germany no matter how unquiet things got on the Western front. But Beals also argues that the literariness of Wheen’s translation often doesn’t align well with the plainspokenness of the German text, and that it sometimes undermines the plausibility of the narrator’s voice. In the original, Bäumer—though far from an everyman—still sounds like a 19-year-old, or at least what you might expect a well-educated, 19-year-old German soldier-storyteller to have sounded like at the beginning of the 20th century. (Bäumer, we learn, is also something of an aspiring writer.) To cite one of Beals’s examples, Wheen has the young Bäumer use the word “embowered,” already an old-fashioned, purplish locution in 1929, when describing the anti-aircraft artillery concealed in the bushes.

So Beals wanted to produce not a refresh in 21st-century English but rather a translation that matches key facets of the German text better than the de facto standard rendering does. “Where previous translators opted for more elevated diction,” he writes, “I have erred on the side of clarity and concision, using contractions where appropriate and aiming to create sentences, like Remarque’s, that could conceivably be read aloud in a young soldier’s voice.” It’s an eminently sensible plan: If the other Anglophone translators didn’t have among their highest priorities the goal of retaining aspects of the text to which one might reasonably ascribe real importance, why not prioritize those aspects in a retranslation? The next question to ask, of course, is: How effectively does Beals deliver on his approach?

Overall, he gives us an English rendering of the novel that does go farther than Wheen’s in preserving the directness of the original. Consider another example from Beals’s introductory essay: Wheen translates the line “er ist es noch, er ist es nicht mehr” as “he it is still, and yet it is not he any longer.” This version follows the paratactic German syntax quite closely, but it also forfeits much of the German text’s simplicity. In English, holding to the nominative form of the pronoun “he” sounds lofty or hypercorrect when that pronoun plays the role of predicate nominative, something that isn’t at all the case in German. Furthermore, when you put such a predicate nominative at the beginning of a clause, this tends to land as oratorical in English (“he it is”), which also isn’t the case in German. Beals, by contrast, gives us “he’s still here, but then again, he’s not here anymore,” which is about as simple and colloquial as Remarque’s German formulation.

There is, however, a problem, one not driven by a particularly difficult translation challenge. The words in question run through Bäumer’s head as he looks at the body of a friend who’s dying in a hospital. They can be interpreted in different ways, needless to say, and “er ist es” can in fact mean “he is here.” Still, that meaning doesn’t accord with the context at hand, since it goes with the question “who is there?” much more than with the question being raised: “Who (or what) is that?”

The context here strongly suggests that the “it” (“es”) in the phrase “er ist es,” which Beals drops, is a key element. Coming directly after a sentence that begins with “There lies our comrade,” “it” appears to refer in the first place to the friend’s body. For Bäumer reflects precisely on how the body is still the friend, how he can still see in his friend’s face the lines “we know so well because we’ve seen them a hundred times,” lines that thus still help make the friend himself, a unique individual. Yet those lines have “already” become “strange,” because the body has already been transformed by death, which comes across to Bäumer as “working its way out from the inside,” blurring the friend’s “image.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →It’s not inaccurate to render Remarque’s line as Beals does: Part of the point is that the friend is already dead, to a large extent, yet still alive, and in that sense still with us—still “here.” But to say that the man dying in front of you is still here yet no longer here is to bring into play the language of an immaterial essential self leaving a body, whereas Bäumer, with bodies being blown apart all around him, focuses on or posits the very materiality of personhood. So, on the level of association, that “he’s still here” lacks the sensitivity you hope to encounter in a literary translation. Of course, this is just one line out of the thousands the book contains, and even the best literary translations are vulnerable to selective critique, where someone dwells on nonrepresentative moments of lapse with respect to things like association and register. In this case, however, Beals himself did the selecting, singling out “he’s still here, but then again, he’s not here anymore” as a successful translation—a clear improvement over Wheen.

Beals tries to get closer to the German than Wheen in other ways, too, reproducing Remarque’s paragraph breaks and giving direct translations of idiomatic phrases, even when the result isn’t an established figure in English (“skinny as a fish,” and so on). And a dissonance that does noticeably recur in Beals’s otherwise quite readable translation has to do with how these moves can clash with his aim of preserving the colloquial feel of the source text. In consecutive sentences, for example, we get the formulations “it was smelling mighty fatty” (a colloquializing, rather free translation of Bäumer’s description) and “who thinks the clearest of us all” (a very direct, non-colloquial rendering), when here the register of the German text doesn’t change.

Shifting translation priorities from sentence to sentence isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but in this case, it makes the novel seem, at least to me, less well-crafted than it is—and as Beals himself stresses, All Quiet on the Western Front is a very well-crafted novel. Aside from the much-praised vividness of its battle scenes, it features a pacing that prevents the reader from becoming numb to the carnage, as well as a subtle psychological movement on Bäumer’s part that’s quite difficult to describe: a creeping disillusionment and resignation, except that it’s not quite that either, since Bäumer didn’t enter the war with high ideals, and his fight for survival ends only with his death.

Perhaps the centenary of All Quiet on the Western Front will bring further English translations; let us hope so. In the meantime, Remarque’s classic World War I novel will continue to speak to Anglophone readers, both those who are encountering it for the first time and those who are returning to it again. The rendering that Beals has provided will allow these readers to appreciate more fully important features of the novel—features that, as Beals points out, go far in explaining what has made this literary evocation of life on the Western front so extraordinarily influential and, sadly, evergreen.

More from The Nation

The Exposure Therapy of “A Private Life” The Exposure Therapy of “A Private Life”

In her new film, Jodie Foster transforms into a therapist-detective.

How to Build a Moon Garden When the News Is All Horror How to Build a Moon Garden When the News Is All Horror

The Riotous Worlds of Thomas Pynchon The Riotous Worlds of Thomas Pynchon

From “The Crying Lot of 49” to his latest noirs, the American novelist has always proceeded along a track strangely parallel to our own.

Letters From the March 2026 Issue Letters From the March 2026 Issue

Basement books… Kate Wagner replies… Reading Pirandello (online only)… Gus O’Connor replies…

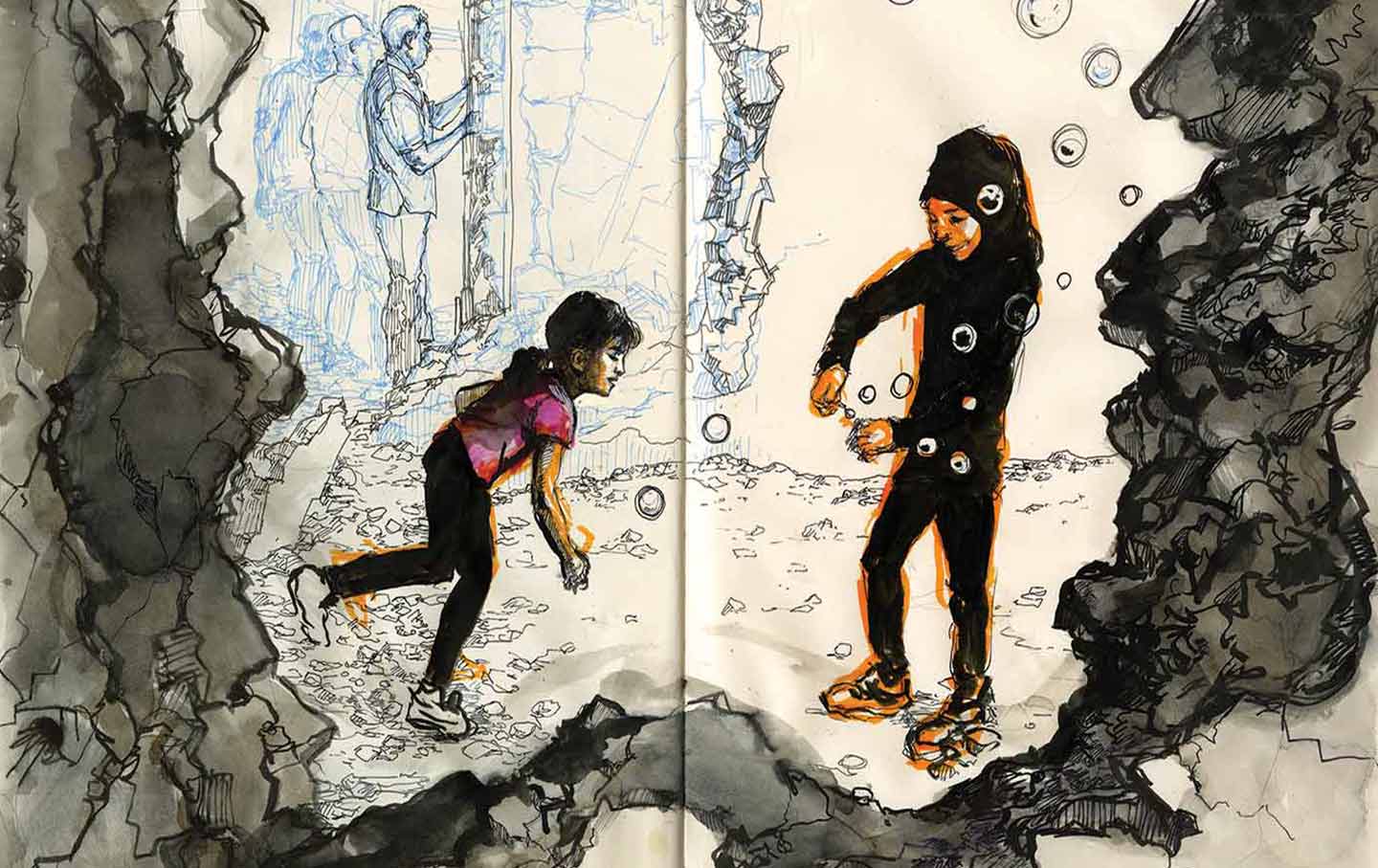

Molly Crabapple's Time Capsule of Resistance Molly Crabapple's Time Capsule of Resistance

A new set of note cards by the artist and writer documents scenes of protest in the 21st century.