ADRIAN BELLESGUARD

ADRIAN BELLESGUARD

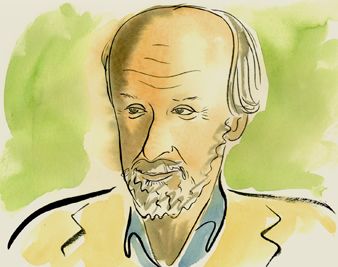

E.L. Doctorow’s new novel, Homer and Langley (Random House; $26), imagines the lives of New York’s famous Collyer brothers, prosperous eccentrics who dropped out of society and filled their town house with collections of obsolete, strange or otherwise broken-down objects. Doctorow’s narrative extends into the late twentieth century, but the real-life Collyers were found dead in 1947, Langley felled by the traps he had laid for intruders and Homer, who is blind, a victim of starvation. –Christine Smallwood

What was your research process like?

I didn’t do any research. I just used what I knew. I was a boy when they died: the whole house was discovered to be what it was, and it became instant folklore. Instant. And when my room was sloppy my mother would say, It’s the Collyer brothers! I did look at photographs. I took the position that they were folklore, they were mythology, and that not research but interpretation was the proper response.

The Collyer brothers remind me a bit of Grey Gardens.

I never made that connection. I would make a distinction–the meaning I find is quite different. I just regard those women as kind of pathetic, dysfunctional messes. But I always had a feeling that these guys, there was a secret to them. Because they’d come from a well-to-do background and opted out. That was the essential idea in my mind. Go in the house, close the door, pull down the shutters, isolate yourself from the surrounding world. It was a kind of emigration. They were leaving the country. I regarded the book as a form of breaking and entering. They lived in their imaginations.

It’s also a novel about stuff.

Accounts have called them pack rats. I think that’s a demeaning, inadequate phrase. What they are is aggregators. The things they bring into the house–there’s a history there of the things we’ve thought we needed over time. At this point I think the book becomes imponderable. You can say it’s about inevitable human isolation. You can say it’s about entropy. You can say it’s about the end of an empire. I tend to agree with any reasonable interpretation. Anyway, all of us feel we need an awful lot. And the technology keeps changing, but the minute any technology appears it becomes indispensable.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →Do you have any thoughts about the Kindle or e-readers?

I don’t use one. I can understand why if you’re on an airplane going around the world, you’d want a Kindle. But I think books are great technology. Once they’re produced they don’t use any energy. If their materials are decent and sound, and you take care of them, they’ll last forever. I like the feel of a book, I like to turn pages, I like to see print on paper. The pleasure of going into a bookshop, finding things you didn’t even know you were looking for, discovering things–that’s what we’re losing now. Everyone knows in advance what they want, and they order it online or download it.

Homer and Langley seem particularly "New York."

Yes. You can see a lot of them on the street, even today. That’s why it wasn’t the fact that they collected things that got me going but who they were, the metaphors they created in my mind. They’re people who opted out. One of my friends found a comparison with Melville’s story "Bartleby, the Scrivener." That withdrawal. Yes, it’s New York, but it’s also American. The Beats, that was a form of withdrawal. I wrote a story years ago about a fellow, an eccentric up in Westchester County called the Leather Man. He was all dressed in animal skins and plates of leather and a big leather hat, like a Viking. He carried a staff, and he lived wandering through the woods. People would give him food. He was totally benign but shy. He lived as a wandering hermit.

Yet Homer and Langley don’t travel light. What kind of opting-out is it to take the world into your home like a museum?

Making another world, pulling the world in after you. But it’s a different world: a symbolic world, a doomed world. They are premature archaeologists. The novel is really anything but a psychological study of dysfunction. They’re engaged in trying to create meaning for themselves and a life that makes sense to them. They have convictions. There are two images that I like from the book. One is when they’re tied to the chair back-to-back in the kitchen, and Langley delivers a speech about this ideal community. The other is when they’re riding a bicycle built for two down the street. The price of writing things is, you’re the instant reader, and you make these discoveries–they’re coming through your fingers as you’re typing; you don’t think of them as mental operations. Then you read what you’ve written, and you laugh.

What are you reading now?

I’ve been rereading Chekhov, some new translations of the great novellas.

>What are you learning from Chekhov?

I don’t know if I can learn anything from Chekhov. He’s such a surpassing genius. You can figure out how a book works, break it down into its parts. But it’s almost impossible with Chekhov. He splashes the words out on the page, in a seemingly artless fashion, with no particular aesthetic principle or interest in the craft. How does he write paragraphs? You don’t get any sense of aesthetic organization. Time passes, people complain, nothing happens, something happens–it just sort of spreads out. Of course, there’s great art in that seeming artlessness–this could happen then or five pages later; it doesn’t really matter. So you can’t learn from that. You just are in awe.