Bolsonaro’s Conviction Was Decided by the Only Woman on the Brazilian Supreme Court

Minister Cármen Lúcia Antunes Rocha cast the deciding vote, defying the extreme right’s misogyny and sending a strong message to Bolsonaro ally US President Donald Trump.

Former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro gestures as he speaks to the press at the Federal Senate in Brasília on July 17, 2025.

(Mateus Bonomi / AFP)

In a landmark decision last week, the Brazilian Supreme Court convicted former president Jair Bolsonaro and six of his allies of attempting a coup d’état after losing the 2022 presidential election. The decision strengthens Brazilian democracy and sovereignty during an era of fascist, extreme-right governments unreservedly and unapologetically attacking the rights of marginalized people globally. But perhaps even more notably, it was a woman—the only woman on the Supreme Court—who cast the deciding vote, derailing the extreme right’s continuous campaign to silence women politically in Brazil and beyond.

Originally from the state of Minas Gerais, Supreme Court Justice Cármen Lúcia Antunes Rocha, 70, is only the second woman to join the Supreme Court. She has been at the center of some of the most controversial votes in the court’s history, including the 2018 conviction of the current president, Luiz Lula Inácio da Silva, which infuriated left-wing movements at the time. His imprisonment was later overturned by the same court that found the proceedings had been politically motivated to stop Lula from running for president. Avoidant of fame and glamour—people close to Rocha describe her as a “simple person”—as well as party politics, Rocha has spoken out about the lack of female representation in the legal field and Brazilian women’s lack of full rights.

From the exclusion of full abortion rights from the 1988 Constitution to the impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff in 2016, the extreme right in Brazil has fought tooth and nail to keep women and women’s rights out of politics.

When casting her vote, Rocha said that “a Brazil that hurts pulsates in this case, almost a meeting of Brazil with its past, present, and future,” referencing the 20 years the country was under a dictatorship. This history—and the fear that it would repeat itself—is precisely why Brazilians have been closely watching Bolsonaro’s trial, which began on September 2.

From 1964 to 1985, Brazil was under a military dictatorship, supported by the United States, which sought to win the ideological war against communism on the continent. As soon as President João Goulart was deposed by military conspirators in 1964, the US quickly recognized the newly established antidemocratic government as legitimate, and even planned to send military reinforcements in case a civil war broke out. Even before that, the US government had been injecting money into opposition campaigns, hoping to beat Goulart at the polls. A defining characteristic of the Brazilian dictatorship was its religious conservatism, an ideology that insisted on keeping women out of politics and in the home. This exclusion of women, along with the history of women’s subjugation before it, was briefly cited by Rocha when her colleague Flávio Dino interrupted her speech: “You can speak quickly—because we women were silenced for 2,000 years, we want to have the right to speak,” she said, jokingly. “But I concede the floor, as always.”

In the last few years, the alliance between the extreme-right evangelical movements in the United States and in Brazil has threatened to repeat this history, with Donald Trump and Bolsonaro using very similar playbooks that incite hate, spread fake news, and construct antidemocratic parallel realities. Those parallels overlapped in more recent history as Bolsonaro’s incitement of his Brazilian supporters mirrored the January 6, 2021, insurrection in the US. Like Trump’s supporters who stormed the Capitol, Bolsonaro voters invaded and vandalized government buildings in hopes of overturning a democratically run election because their candidate did not win. Just like Trump, Bolsonaro cast doubt on the highly reliable and auditable Brazilian voting system by calling for paper voting, claiming to have evidence that he won in the first round of elections in 2018, and alleging without producing any evidence that a hacker had tampered with the electronic voting system. When it was definitive that Lula would be sworn in, Bolsonaro called upon the military to stop it. All of these actions are supported by a wealth of evidence Bolsonaro and his allies produced against themselves—including WhatsApp messages, meeting notes, and livestreams where Bolsonaro incited his voters—when plotting to spread misinformation about the electoral process and calling in the military to stop Lula from being democratically sworn in. Bolsonaro’s allies include Gens. Augusto Heleno, Walter Braga Netto, and Paulo Sérgio Nogueira, Brazilian Navy Adm. Almir Garnier, and federal police deputies Alexandre Ramagem and Anderson Torres, who will be the first military members to be jailed for antidemocratic action.

Rocha’s vote to convict Bolsonaro and his allies directly pushes back on the alternate realities right-wing extremists depend on to win elections and provoke attacks on democratic institutions. Bolsonaro and his supporters kept insisting they deserve amnesty—before being convicted of any crime—and that the people who attacked Brazilian Congress on January 8, 2023, were old, vulnerable, and knew not what they did. But in casting her vote, Rocha focused instead on the reality of their antidemocratic actions. “The events of January 8, 2023 were not banal,” Rocha said, describing the events as a year-and-a-half-long effort to “incite, maliciously influence, instigate, and assault individuals and institutions through various crimes leading to acts of vandalism.”

Here, Rocha is referring to Bolsonaro’s continuous efforts to cast doubt on the Brazilian voting system, a process that started in July 2021, when he questioned the electronic system without evidence in a livestream. From that moment on, social media platforms were filled with misinformation about Brazil’s electoral process, preparing the country for a potential coup in case Bolsonaro lost in the 2022 elections. During the election, this disinformation had been flagged and mitigated by the country’s electoral court, which stepped in to delete misinformation about the electoral process that has been deemed to be fake by the same court. While The New York Times might insist that only one judge, Alexandre de Moraes, has regulatory power over social media content, regulating and stopping inflammatory misinformation is essential to defending democracy.

American institutions that purport to safeguard democracy and free speech should try similar mechanisms.

Defending Brazilian democracy and sovereignty also includes pushing back against President Donald Trump’s attempts to intimidate Brazil into submission. Trump has repeatedly threatened sanctions to Brazil and imposed importation tariffs in exchange for Bolsonaro’s full absolution, citing free speech infringement. The sanctions were pathetically requested by Bolsonaro’s son Eduardo, an intervention that is demonstrative of the childish authoritarianism of technofacism, where anything contrary to the desires of the toddler-like leader is considered an infringement of freedom, and where calling for illegal and undemocratic actions online is considered a valid call for help.

The connections between the neofascist movements in Brazil and the USA have been widely reported on. However, unlike the US Supreme Court, which has brazenly unraveled democratic norms and legal precedent, the Brazilian Supreme Court has just thrown a wrench at the right-wing insistence that democracy includes the freedom to oppress and silence millions of voters through misinformation, hate speech, and incitement. To protect democracy itself, antidemocratic action and plotting must be stamped out.

Currently under house arrest, Bolsonaro’s sentence—27 years and three months in prison—will be officially published in 60 days, after which his lawyers have five days to file motions for clarifications. There is no possibility of overturning the sentence, though it is likely Bolsonaro will be kept under house arrest for the duration of his sentence, as he announced a diagnosis of early-stage skin cancer following the conviction. This will disappoint some of his opposition, as many were hoping to see him behind bars. But as long as he isn’t able to run for office, Brazilian democracy has been secured.

Historically and presently, this conviction reasserts Brazilian sovereignty and rejects Trump’s attempt to return to the country’s Cold War policy of US-backed dictatorships in Latin America. In seeking business deals with other countries, President Lula signals that US imperialism is faltering, and that soon, Global South nations will no longer need the neocolonialism of US investments. Within this context, it isn’t surprising to see the Trump administration have a tantrum at the prospect of one of Trump’s biggest allies being jailed for actions almost identical to what Trump has done in the US.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Bolsonaro’s conviction signals that there are ways to reckon with antidemocratic conspiracies—if only US institutions followed Brazil’s lead.

Brazilian democracy is still fragile, as the Chamber of Deputies recently passed a bill that eases the length of time convicted politicians are forbidden from running for office. I continue to question the effectiveness of democracy in capitalism in representing all people, particularly as a person with a uterus who does not have full rights over my body. But Rocha’s vote was the last nail in the coffin of a misogynist’s world-building that forbade women from even being allowed to speak, let alone vote. And for that, I’ll raise a glass.

Time is running out to have your gift matched

In this time of unrelenting, often unprecedented cruelty and lawlessness, I’m grateful for Nation readers like you.

So many of you have taken to the streets, organized in your neighborhood and with your union, and showed up at the ballot box to vote for progressive candidates. You’re proving that it is possible—to paraphrase the legendary Patti Smith—to redeem the work of the fools running our government.

And as we head into 2026, I promise that The Nation will fight like never before for justice, humanity, and dignity in these United States.

At a time when most news organizations are either cutting budgets or cozying up to Trump by bringing in right-wing propagandists, The Nation’s writers, editors, copy editors, fact-checkers, and illustrators confront head-on the administration’s deadly abuses of power, blatant corruption, and deconstruction of both government and civil society.

We couldn’t do this crucial work without you.

Through the end of the year, a generous donor is matching all donations to The Nation’s independent journalism up to $75,000. But the end of the year is now only days away.

Time is running out to have your gift doubled. Don’t wait—donate now to ensure that our newsroom has the full $150,000 to start the new year.

Another world really is possible. Together, we can and will win it!

Love and Solidarity,

John Nichols

Executive Editor, The Nation

More from The Nation

Brace Yourselves for Trump’s New Monroe Doctrine Brace Yourselves for Trump’s New Monroe Doctrine

Trump's latest exploits in Latin America are just the latest expression of a bloody ideological project to entrench US power and protect the profits of Western multinationals.

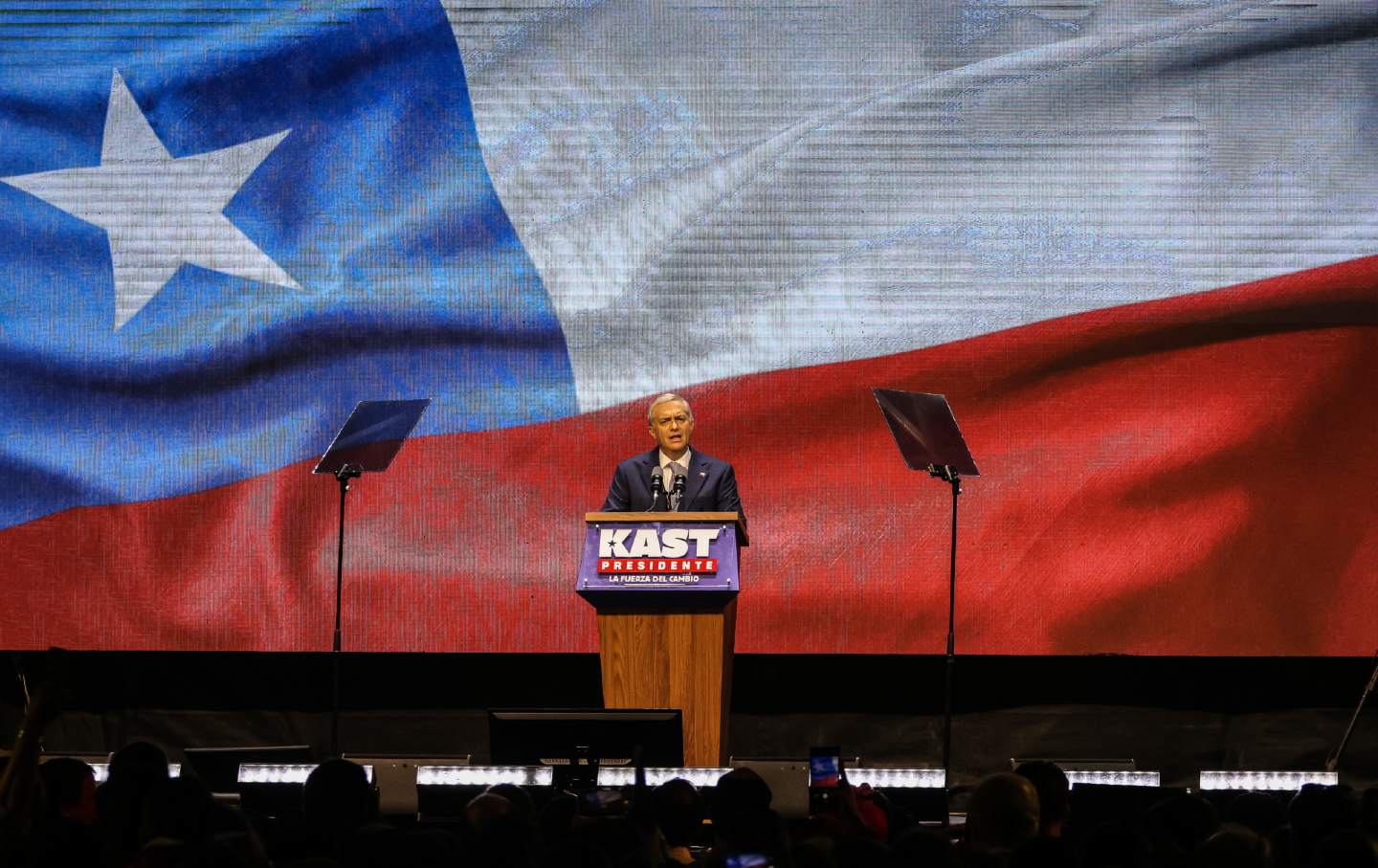

Chile at the Crossroads Chile at the Crossroads

A dramatic shift to the extreme right threatens the future—and past—for human rights and accountability.

The New Europeans, Trump-Style The New Europeans, Trump-Style

Donald Trump is sowing division in the European Union, even as he calls on it to spend more on defense.

The United States’ Hidden History of Regime Change—Revisited The United States’ Hidden History of Regime Change—Revisited

The truculent trio—Trump, Hegseth, and Rubio—do Venezuela.

Mahmood Mamdani’s Uganda Mahmood Mamdani’s Uganda

In his new book Slow Poison, the accomplished anthropologist revisits the Idi Amin and Yoweri Museveni years.

The US Is Looking More Like Putin’s Russia Every Day The US Is Looking More Like Putin’s Russia Every Day

We may already be on a superhighway to the sort of class- and race-stratified autocracy that it took Russia so many years to become after the Soviet Union collapsed.