What Are Drugs For?

A conversation with P.E. Moskowitz about the chemical imbalance theory of depression, the false schism between prescription and recreational drugs, and collective psychic pain.

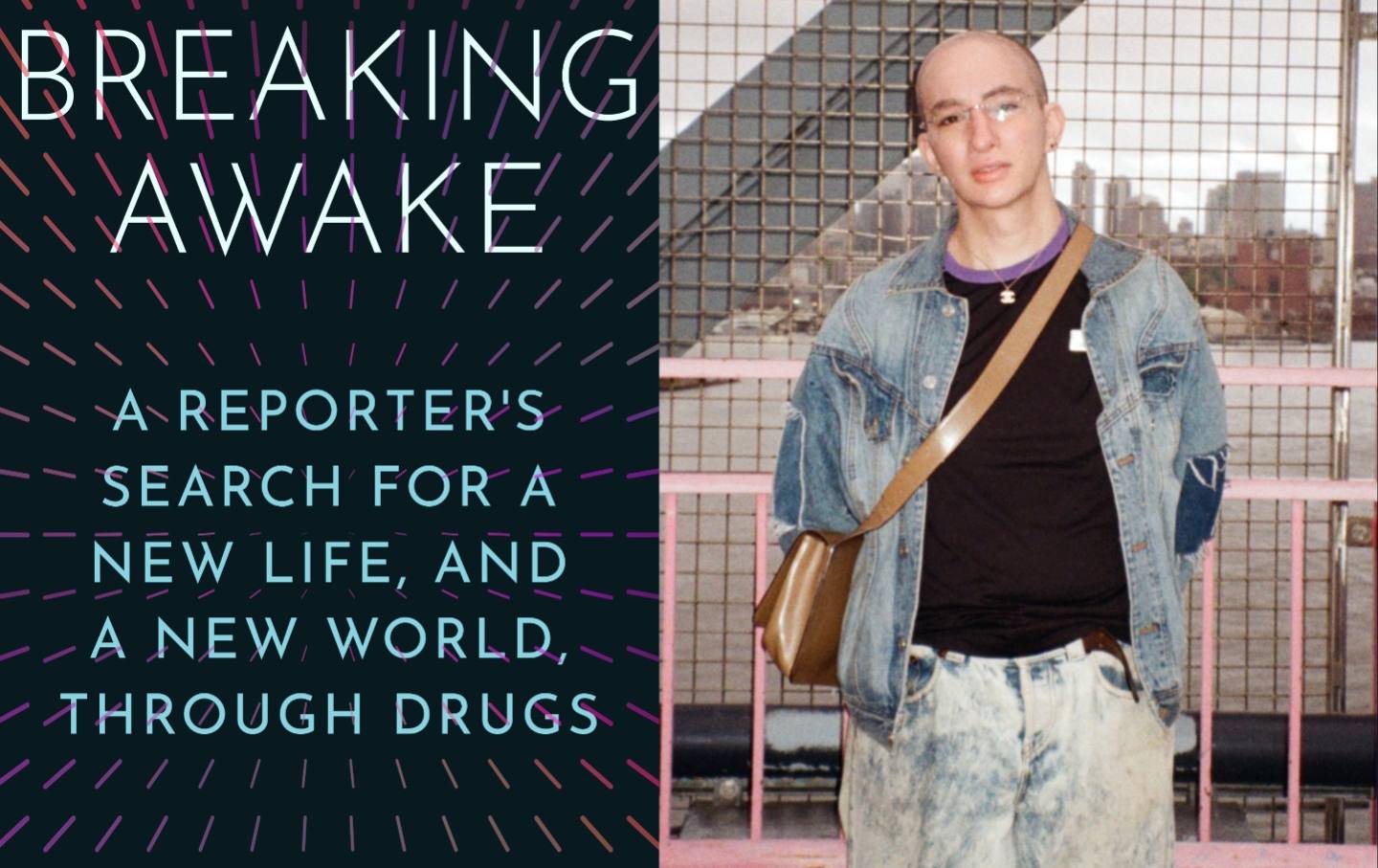

P.E. Moskowitz

(Kacper Koleda)Awoman gnaws at her nails: one hand in her mouth, the other clutching the shaft of a mop, which serves as one bar of a prison cell composed of cleaning products. It’s an apt metaphor. In mid-century America, housewives were expected to polish their own gilded cages without considering how their feelings of entrapment might be related to their imprisonment in suburban homes. But by the late 1960s, even advertisers recognized that women might find such lives a little upsetting after reading The Feminine Mystique.

The aforementioned woman is a model in a 1967 ad for a tranquilizer called Miltown. The ad acknowledged that the drug “cannot change her environment…but it can help relieve the anxiety” caused by her conditions. Ten years prior, Miltown had swept the market, selling over a billion units in the decade after Wallace Laboratories debuted it. In ads for Miltown, pharmaceutical copy suggested an incompatibility between liberatory social movements and surviving the suburbs might be to blame for a woman’s anxious distress. Nonetheless, they had a solution: A pill would go down more smoothly than a revolution.

P.E. Moskowitz deftly deconstructs this ad in a scathing examination of today’s psychopharmaceutical industrial complex in their third and newest book, Breaking Awake: A Reporter’s Search for a New Life, and a New World, Through Drugs. A memoir of their own breakdown and attempted recovery via psychopharmaceuticals, recreational drugs, and political education, the book is a compendium of psychiatric historiography and field reporting that explores issues they frequently cover in their popular substack newsletter, Mental Hellth. From tranquilizing women out of attempting to transcend their social position to demonizing Black men fighting for civil liberties by diagnosing them with schizophrenia, to the racist divide erected between notions of the “addict” and the “patient,” Moskowitz’s reporting captures the geography of a revolution in storytelling that we were sold as a scientific breakthrough.

These re-narrativizations of politicized rage and leftist striving were early steps in a grand reframing of mental health that Moskowitz traces to the monotonous, inert landscape that is today’s conception of psychic pain, where the “chemical imbalance” theory of depression reigns, and antidepressants are the assumed solution to a vast range of complaints, often as political as they are emotional. Moskowitz wields their analyses of scientific studies, marketing campaigns, harm reduction techniques, and their own experiences to dissect the story the psychopharmaceutical industry has sold to us: less a “medical innovation” than a “narrative” one. With stories from raves in warehouses and reporting from experimental harm reduction spaces, Breaking Awake is part polemic, part personal history, and part archeological dig.

Ahead of their book’s publication, The Nation spoke with Moskowitz about the constructed, politicized rift between the medication-dependent patient and the addict, psychic distress, and responses to it from the left and the right. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

—Emmeline Clein

Emmeline Clein: Breaking Awake breaks away, if you will, from most deconstructions of the American drug crisis by considering prescription psychopharmaceuticals like stimulants and SSRIS alongside criminalized drugs like heroin and fentanyl. In doing so, you argue that over-categorization of these substances separates individuals suffering from similar psychic afflictions. Can you elaborate on this?

P.E. Moskowitz: At the top level, I think every drug is used for the exact same reason. That is an oversimplification, but I do believe that the reason over 20 percent of Americans are on antidepressants is the same reason a growing number of people are taking heroin or fentanyl illegally or abusing alcohol or dying from “deaths of despair.” It is also the same reason I see my friends obliterating their brains with GHB and all those “fun” chemicals. It is because we’re all despondent, anxious, and have internalized the violence of capitalism within our own psyches. Obviously, the valences of each drug are different because they each come with different [stereotyped] cultures and class backgrounds. Some people are criminalized for them, some people aren’t. But when we separate [illegal and legal drugs] into “drug” versus “medicine” or “safe drug” versus “not safe drug,” we’re ignoring the fact that we’re all in the same boat. That’s a huge threat to building any form of solidarity; to recognizing that I’m using drugs for the same reason that someone on the streets of Vancouver is.

EC: The story “on the street” so to speak, and the story in the clinic run parallel to each other, yet the medical field has constructed a rhetorical gulf between them. This book crisscrosses the country and the last century, excavating the “narrative innovations” in your words, that have been marketed to us as medical innovations. Can you talk about that distinction and why it is so central to your project?

P.E.M: The narrative around “drugs” versus “medicines” was essentially based on racism. Suddenly, [at the end of the 19th century], competing narratives emerged around the “evil Chinese immigrant abusing illegal opium,” who was cast as a dangerous drug user, versus the white patient understood to be using medically necessary morphine [in the hospital]. Opium and morphine are essentially the same drug. There’s a lot of evidence I cite in the book that white people were using opiates more than immigrants at that time period. But that rhetorical divide still exists to this day. I take Adderall, which is very chemically similar to methamphetamine, but I’m understood by society to be taking medicine, not abusing drugs—and [Adderall] is regulated and given to me at a known dose. It is not contaminated, and I have a doctor monitoring my intake. Meanwhile, people are on the streets using methamphetamine to deal with the same [struggle] I am, but they don’t receive the same treatment.

The most jarring moment in my reporting occurred on a night when I returned to [New York City] from Philadelphia, [where I saw] drug users on the street suffering from lesions, completely abandoned. That night, I went to a friend’s birthday [party] and everyone there was using drugs. Not only was it not criminalized; it was glorified in a way. The people using drugs that night were the kind of people being written up in the Styles section of The New York Times. No one has a problem with them getting high because they’re rich, they’re often white, and they come from a certain cultural background. Meanwhile, the same paper is writing stories about how desperately sad it is that people use drugs on the streets of Philadelphia. The long history of this false divide between medicine users versus illicit drug users is still present today, and is never really questioned. Through my book, through telling my own story about drug use, the connection I wanted to make was, again, no matter where we are or who we are, the modus operandi of society is to force psychic violence into all of us.

EC: Speaking of narrative innovations, your book is deeply personal, but it’s also about something so much bigger than yourself, invested in revealing the way we are all cogs in a capitalist machine. You explain that you see journalism as a communal endeavor, which seems related to your larger solidaristic commitments—how did you come to see your reporting that way, in a field that is often rife with individualistic narratives and in a book that necessarily required your own perspective?

P.E.M: In the kind of journalism I write, especially with this book, I am asking people to tell their stories when they have no reason to beyond wanting to help people. We all have the same goal, and that’s why it feels collaborative. One of my subjects in this book, Melissa, has, in a way, the most normal story in the world. She has a husband and a baby. She is on SSRIs and other medications to keep her functioning, even though she knows something is deeply wrong in the world and her psyche. She wanted to tell her story because she knew that so many people were in the same place as her. Her brother was in the exact same place as her but wouldn’t talk about it. She couldn’t talk about it with friends. She had felt so lonely, not having heard these kinds of stories before. One of the most insidious parts of the individualization of mental health, of thinking of it solely as a chemical imbalance in your specific brain, is not just that it prevents us from understanding the systemic factors that go into mental health. It’s that it prevents us from realizing that we all have similar stories, that we’re in this together, essentially. Everyone I talked to had the same story, just maybe in different fonts.

EC: If mental health is generally thought of as an individual problem, it’s one that seems all parties have gone to great lengths to avoid blaming any one person for creating. There’s almost been a horseshoe effect to avoid victim-blaming: Some embrace a biomedical model of mental health that destigmatizes the problem, while pharmaceutical companies tell the same story to obscure the economic explanations for psychic distress. Either way, an absolved victim is a perfect candidate for an individualistic hero’s journey. What stories do you see instead, in the hollow of the horseshoe?

P.E.M: I love that phrase. I think we’ve actually gone even further, and done a complete 180: The right is more willing to recognize that the issue is systemic, that everyone’s feeling bad because our food system is poisoning us—that’s much of what MAHA is. Robert F Kennedy Jr. points out the most obvious thing in the world: Everyone is unhealthy and sick all the time in America, and something is deeply wrong with that. The things he wants to do about it are extremely stupid.

The left used to do that with mental health—understand it as a response to capitalist society. But neoliberalization trapped liberals and even some leftists in this modality of thinking: “We’ve destigmatized it and that’s all we can do.” It’s all up to you as an individual to address it. Now, no one [liberal] wants to acknowledge this systemic problem anymore because it’s become almost right-wing-coded, which is really sad.

EC: In your book you have a section on the way we’ve been sold “stability” as a goal state. You write about the importance of truly knowing ourselves, in all our complexity, so we can know our enemies—can you talk about the blinders the single-minded pursuit of stability might put on our ability to do so?

P.E.M: The closest approximation I’ve seen in a drug context is at the rave, which is not to glorify the rave scene. As I write in the book, I have many problems with it. But the idea that we can collectively be together and, as Erich Fromm says, “become but one drop on the crest of a wave”—it’s really hard to do any of this individually. When you’re just a body among bodies in a room and probably high on something, that experience enables a realization: a different future is indeed possible. You can be together in this mass and become de-individualized in the best way and realize that your collective power exceeds your individual power by orders of magnitude. But those glimpses are so brief in our society. Whether you’re in a club and the sun comes up and you go back to your normal life, or you’re at a protest that either ends or you get your head bashed in by a cop, we’re very directly punished and indirectly dissuaded from experiencing that feeling because it is very powerful.

My conclusion at the end of the book is: We need to keep searching for those kinds of experiences because it’s not only a matter of starting the revolution, but it’s a matter of life or death survival in this fascistic era. The drugs are not working: The amount of people on prescription drugs has quintupled in the last few decades, and the suicide rate is higher than it’s ever been. If they were working, that wouldn’t be true.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →I almost died in Charlottesville, because a neo-Nazi rammed his car into the crowd. It felt like my two options were, one: try to become stable, which would involve not releasing any of the anger, the fear, the despondency, and distress I felt in the face of the world’s violence and fascism, or two: to reverse the psychic flow of what was put into me outwards. In many ways, this book is my way of getting all of that out. On a societal level, I use the example of prescription drug ads in the 1950s: They were sexist and racist, but in many ways they were also acknowledging systemic realities.

EC: At the raves you discuss, you describe people using psychedelic drugs, which you also write about using yourself to reach revelations, to reframe narratives around mental health. You use Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò’s Elite Capture paradigm, which argues that radical ideas invented by marginalized groups are often co-opted and corrupted by elites who artificially embrace them in order to wield them in service of their own interests, to illuminate the ways Big Pharma attempts to de-radicalize this potentially revolutionary tool by rebranding it as another layer of mental hygiene—which is being done by companies with names like “Woke Pharmaceuticals,” no less.

P.E.M: Drugs are tools. Like any tool, they can be used in a variety of ways. What seems to make our society most comfortable is to take these tools and use them in ways that enable our society to continue as it is. When you look at what’s happening to psychedelics right now, people have realized that they do have an immense power to change people’s brains. So they’re trying to medicalize and professionalize them, so that the way they change people’s brains is very specific: It allows them to keep going to work; it allows them to be more productive; it allows them to feel better about their lives without changing anything about their lives. I think that’s very different than getting really high, say tripping at a rave, because there the point is not to fit yourself back into a society; it’s to realize that the society as it’s been envisioned for you is not necessarily the best form of society. Drugs become a tool to recognize what you actually need in life, that you need more connection to people, sex, bodily movement, whatever it may be. Communal, traditional ways of using drugs have existed for not just centuries but thousands of years. Using drugs to come to some form of revelation or healing has existed in almost every culture.

EC: Your book considers all kinds of drugs as potentially useful tools, but patients and experts you quote predict that the mass prescription of psychopharmaceuticals will be understood by future generations as akin to bloodletting or lobotomies: physically and psychically violent treatments not rooted in scientific evidence. How did you manage the tension between those paradigms?

P.E.M: It’s hard for me to discount the many, many people who have told me that pharmaceuticals help them. I have been helped by Adderall. I have been on [other] prescription drugs that have helped me, and I’ve been on more that have left me in a worse place, but I can’t discount that they sometimes work. What they work for, I think, is the bigger question: Do they help you discover what you need to discover about yourself, your life, or the world to heal? Or do they help you manage the symptoms of your pain so you can get through the day at work? The interesting question is not “Are SSRIs or any other drug good or bad?” I think that’s the wrong question. I think the [better] question is: “How are we using them?”

The problem with SSRI discourse [specifically] is not whether drugs are good or bad, it’s that people see them as cures as opposed to tools, crutches, or salves. At their best, they can ameliorate the pain, but they cannot address the pain. A researcher in the field put it this way: If you have a toothache and you prescribe a pain reliever for the toothache, it helps with the pain, but it doesn’t teach you anything about the infection that caused the toothache. That’s how I see prescription psychiatric drugs now. We’re treating them as if they’re curing the infection that caused the toothache as opposed to treating them as tools to manage the pain of the infection.

More from The Nation

The Endless Hypocrisy of Bari Weiss The Endless Hypocrisy of Bari Weiss

She claims to be a free speech champion. But as her actions at CBS News keep showing, she seems to think free speech should run only in a rightward direction.

What Will Be Left After the University of Texas Destroys Itself? What Will Be Left After the University of Texas Destroys Itself?

UT-Austin has collapsed its race, ethnic, and gender studies into a single program while a new policy asks faculty to avoid “controversial” topics. But the attacks won’t end there...

The Corporate Media Is Head Over Heels for the Iran War The Corporate Media Is Head Over Heels for the Iran War

Donald Trump’s attack may be surreal, unjustified, and illegal. But that’s not stopping the press from turning the propaganda dial way up.

The Disturbing History of ICE’s “Death Cards” The Disturbing History of ICE’s “Death Cards”

The Vietnam-era practice is yet another example of ICE agents thrilling to the brutality they have been encouraged to cultivate.

The American Universities Programming Israel’s Killer Drones The American Universities Programming Israel’s Killer Drones

Industry partnerships in higher education are pushing STEM graduates into the business of weapons manufacturing and genocide profiteering.

The Red State–Blue State Healthcare Divide Is Dangerous for Everyone The Red State–Blue State Healthcare Divide Is Dangerous for Everyone

Whether or not you have access to independent, scientifically sound public health guidance may depend on how your state voted for governor.