The World Chaim Grade Lost

The Yiddish writer’s lost masterpiece, Sons and Daughters, brought back to life, in all its humor and beauty, the Jewish shtetl of his youth.

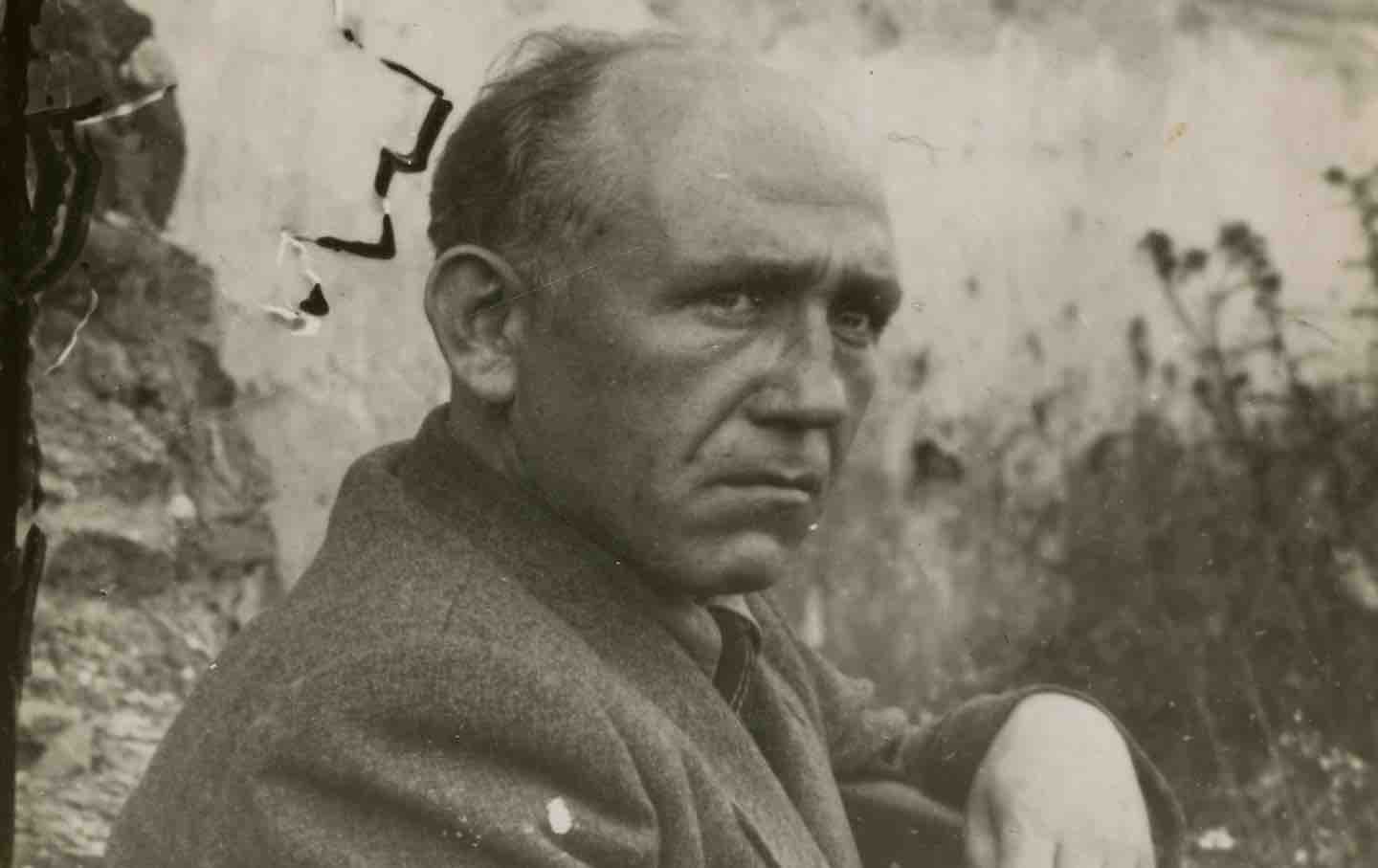

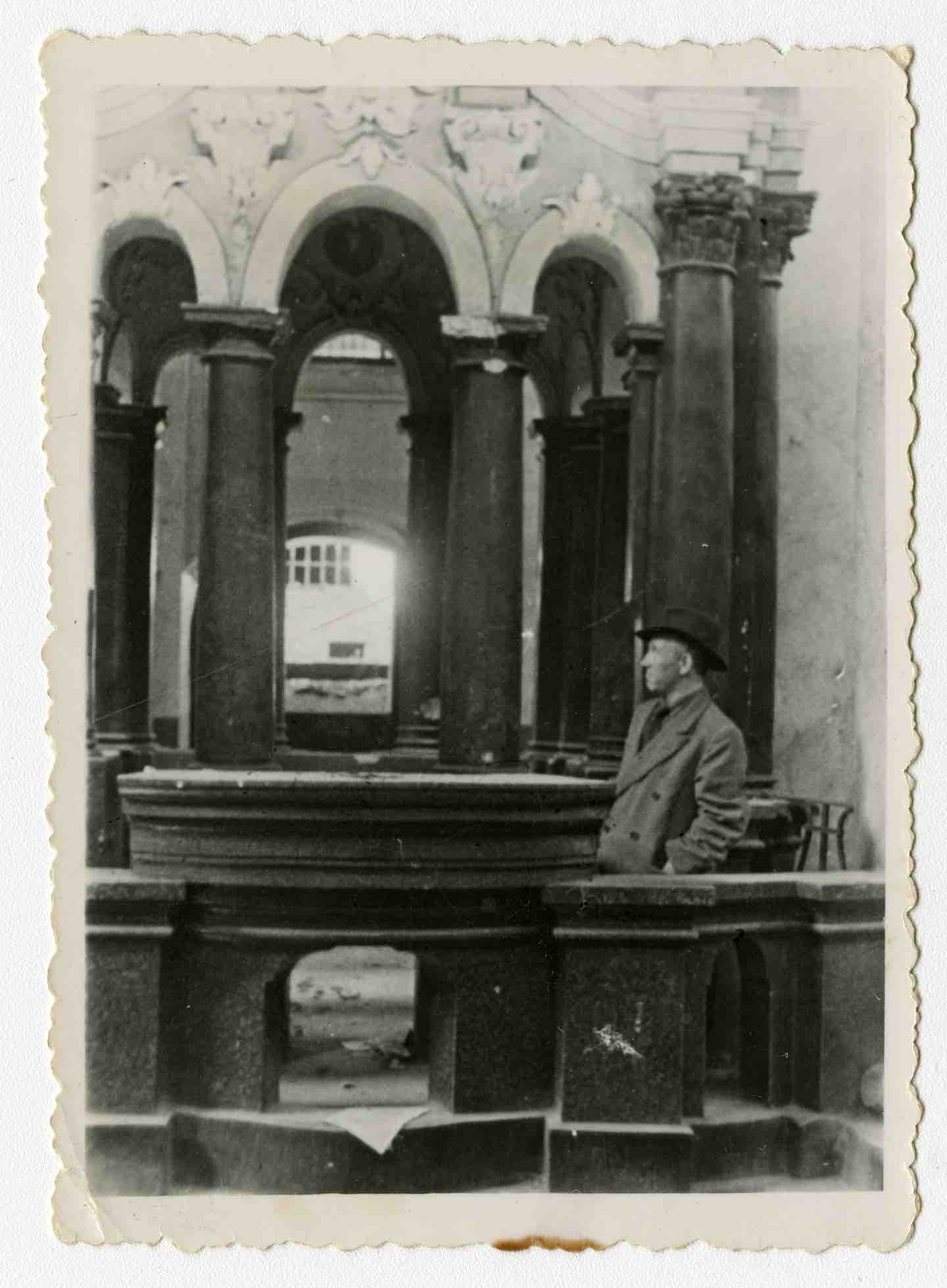

Chaim Grade in Vilne, Lithuania, 1945.

(From the Archives of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York)When the Yiddish-language novelist Chaim Grade was in his 60s and living in the Bronx, he wrote in a letter to a friend, “The writer inside me is a thoroughly ancient Jew, while the man inside me wants to be thoroughly modern. This is my calamity, plain and simple, a struggle I cannot win.” It’s easy to imagine how torturous this inner tug-of-war was for Grade, who grew up highly observant in Lithuania in the early 20th century, then rebelled against yeshiva study and rigorous Orthodoxy to pursue a life in letters. To become a writer—and one who published not in Hebrew but in Yiddish—was a scandalously modern thing for him to have done at the time.

Books in review

Sons and Daughters

Buy this bookAt the start of World War II, Grade went into hiding in the Soviet Union, believing that, as women, his wife and mother would be safer at home; after the war, he found out that both had been casualties of the Holocaust. Grade emigrated first to Paris, where he remarried, and then to the United States, where he lived a life that he could hardly have envisioned during his yeshiva boyhood. Meanwhile, the community and culture in which he’d grown up, among the shtetl Jews of Lithuania, Poland, and the rest of the Pale of Settlement, was no more. The “thoroughly ancient Jew” in Grade had no home to return to—except in his writing.

Grade took seriously his fiction’s ability to re-create this destroyed society. He called himself the “gravestone carver of my vanished world,” though the universe his fiction conjures is hardly gray or grim. Quite the opposite, in fact: His colossal novel Sons and Daughters, which is appearing for the first time in English this year after a long struggle of its own, is a rollicking, vivid delight. In 1983, a year after Grade’s death, his widow, Inna, sold Knopf the English-language rights to Sons and Daughters, which Grade had published in serial form in two American Yiddish newspapers from 1965 to 1976. It was a hit among its Yiddish readers, and English speakers enjoyed Grade’s other work: Inna’s 1982 translation of his story collection Rabbis and Wives with Harold Rabinowitz, a former rabbi from the Boston suburbs who moved to New York to work with the Grades, was a runner-up for the Pulitzer Prize, losing to The Color Purple. (Rabinowitz would later recall that Chaim and Inna “struck [him] as an incongruous couple. [Chaim] was a short, bald, squat chain-smoker, and she looked like a movie star.”) Inna was meant to begin work on an English translation of Sons and Daughters not long after selling it. Instead, she stopped communicating with Knopf and holed up in her apartment with Grade’s papers, neither translating them nor allowing anyone else access. Shortly after her death in 2010, archivists from the YIVO Institute of Jewish Research were given permission to begin searching for the manuscript of Sons and Daughters, which, as a serialized novel, they assumed would have to be reassembled. By 2015, they’d unearthed enough that Knopf was finally able to commission Rose Waldman to translate the book it had bought 22 years earlier. In her afterword, Waldman writes that she’d signed an agreement to produce a text that “would be about 450 pages long [and] was a completely finished novel. None of that turned out to be true.”

Sons and Daughters, in its English incarnation, is well over 600 pages and decidedly lacks an ending. Grade, evidently, disliked the conclusion to which he’d brought the story in 1976 and decided to redo it, then died before he could. From a readerly perspective, Sons and Daughters would be no less enjoyable if it were even longer, and its lack of an ending is unimportant. This is not a novel you read for the plot but for a world to sink into, a sprawling yarn that unspools in hugely entertaining detail, encompassing all the ingredients of life—sex, money, domesticity, religion—that we want in a realist novel. It’s so lifelike, in fact, that it feels appropriate—and, in some ways, maybe even a blessing—that it just ends where it ends.

Sons and Daughters follows the travails of Sholem Shachne Katzenellenbogen, an aging rabbi living in a small Polish town, and his children, relatives, enemies, and friends. Sholem Shachne, a pillar of his highly observant community, is suffering profoundly over his adult children’s unanimous refusal to live in the way the Katzenellenbogens had for generations. One of his daughters, Bluma Rivtcha, wants to be a nurse, and the other, Tilza, can’t stop “look[ing] around her in the midday brightness with dreamy, nocturnal eyes,” even though she’s married to a nice young rabbi and is supposed to be focused on keeping his home. (Unlike her sister, there’s no one thing Tilza would rather pursue; what she wants is simply to dream.) As for Sholem Shachne’s sons, the situation is dire: One is a business student, another ran away from yeshiva to study philosophy in Switzerland, and the third wants to emigrate to Palestine.

Sons and Daughters is set in the 1930s, before the horrors of the Nakba. Refael’ke, Sholem Shachne’s youngest son, is part of a Zionist movement to establish a Jewish state in what was then known as Mandatory Palestine—a notion that Sholem Shachne, like nearly all the religious Jews of his time, rejects completely. He believes that Jews have no business in the Holy Land until the Messiah summons them there. But he’d hardly be happier if Refael’ke wanted to join his brother Naftali Hertz in the Swiss Alps or emigrate to that other country drawing Jews en masse from Eastern Europe: Sholem Shachne considers the United States a “treyf country” (treyf is the opposite of kosher) where the “wagon of Judaism [has] rolled down the hill and tumbled over.” He fears that within his own family, the same process is unfolding.

Grade roams freely from Sholem Shachne’s various child troubles to those of his father-in-law, Eli-Leizer, a rabbi in another small shtetl, and his friend Zalia Ziskind, a famed Torah scholar brought low by depression. The three men’s shared gripes about their modernized children hold together a novel that, without its common themes, would otherwise seem like a giant bag of anecdotes. But while an episodic tale united by parental groaning may not sound appealing, and while Sons and Daughters isn’t exactly propulsive, it’s anything but plodding or glum. Instead, it absolutely crackles with humor, energy, and the animating spirit of community.

Sons and Daughters is a populous novel, and Grade has a remarkable ability to fully conjure a character with a one-line description (often, if the character in question is male, of his beard), and it’s endlessly fun to watch him do it. Grade is not above a little meanness—he describes one unpopular relative as “the wooden noodle, Banet Michelson”—and neither are his characters. For all the rabbis’ great learning and spiritual elevation, they’re petty as hell. One of the book’s most entertaining installments concerns a war of words between Eli-Leizer and a less religious rabbi whose new synagogue competes with his. Eli-Leizer tries to undermine the rogue temple by declaring that its cantor, who is also the local kosher butcher, spends too much time thinking about singing and not enough on his day job—which, in theory, could mean that he’s not providing properly kosher meat to his customers. As far as the novel’s characters are concerned, this is high drama, but Grade doesn’t play it straight: He introduces a jester, Eli-Leizer’s troublemaking son Shabse-Shepsel, to caper through the battle of the cantor-butcher, calling everyone’s behavior into question and provoking cringes and laughter.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Sons and Daughters is a surprisingly sensuous novel as well: Grade’s characters enthuse about “breasts like pumpkins” and “svelte legs with such rounded knees they aroused all men, even a Katzenellenbogen who was no great connoisseur of women’s legs.” Its sensuality spills into the natural world: On a sunset hike in the Alps, Naftali Hertz looks at a peak called the Jungfrau, German for virgin, and imagines “the head of the mountain known as ‘the black Mönch’…suckling from her bare navel” while the surrounding mountains watch “with glowing red faces, as if burning with romantic jealousy.” This moment prefigures Grade’s own marital woes while also demonstrating that, although his novel is set in a community where sex is meant to occur only inside a marriage, the potential for pleasure is everywhere. It’s even in poor Sholem Shachne’s house, where his youngest daughter, Bluma Rivtcha, brings home a poet fiancé—a crisis in and of itself: Sholem Shachne is horrified that she wants to marry “a boy who threw away the Torah and publishes little poems”—and has sneaky out-of-wedlock sex with him.

It’s hard not to feel for the elderly rabbis of Sons and Daughters: Their world is melting away. But Grade never once looks up from his characters’ immediate concerns to the thing that menaces them most: not modernity or secularism; not the communism that seduces Zalia Ziskind’s son Marcus or the Zionist fervor that sweeps Refael’ke away; not even the Christian Poles’ boycott of Jewish businesses in the small towns where Sholem Shachne and Eli-Leizer live, which is the main form of antisemitism visible in the text; but, of course, the Holocaust. Not one character in the book seems aware of the rise of Nazism, and there are no gestures toward it either. Grade never foreshadows the war or the death camps or allows the reader’s awareness of them to take us out of the society he’s describing. Instead, with all his lush, granular, focused detail, he plunges us in.

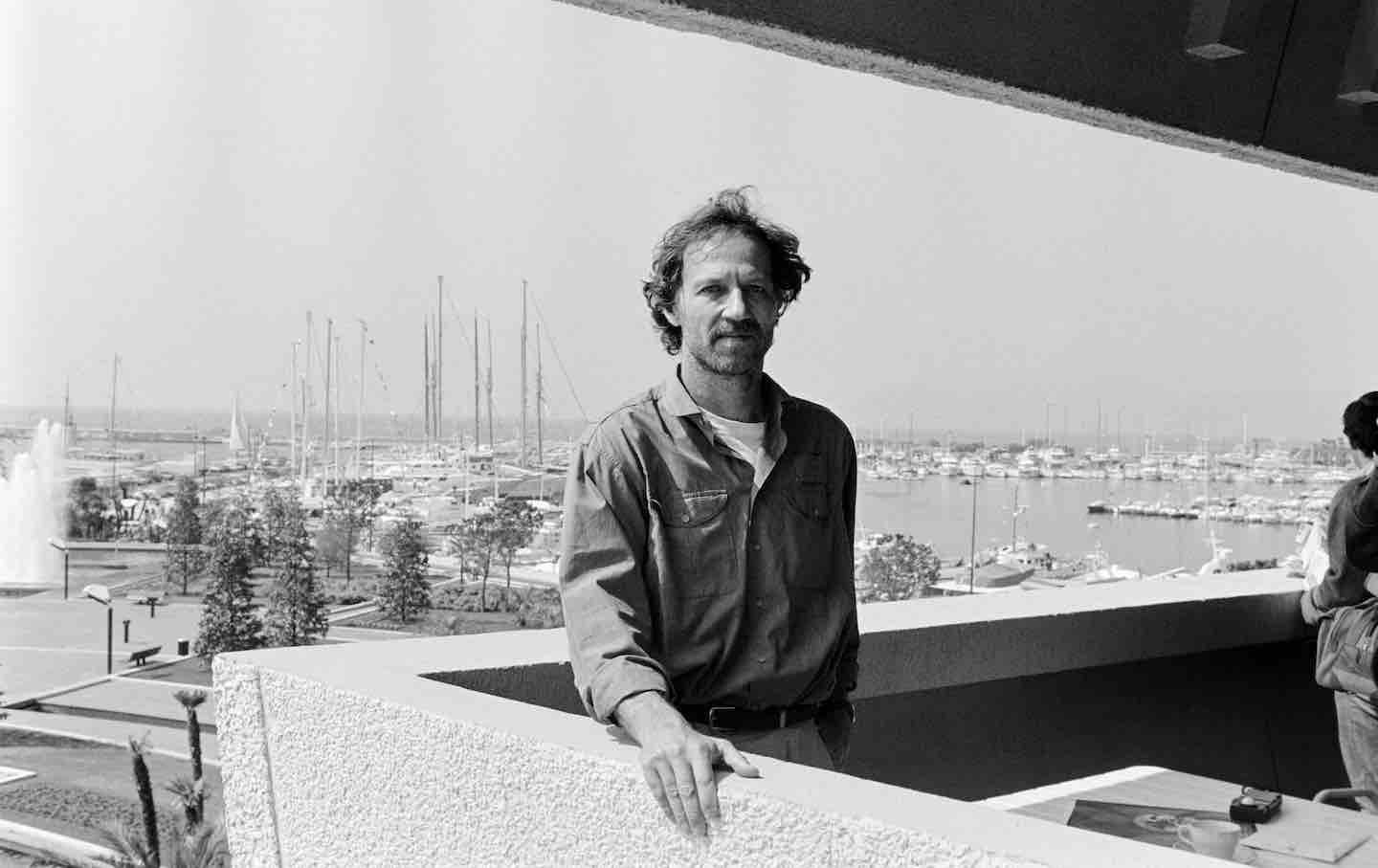

Grade’s refusal to admit his knowledge of the characters’ future into their present is at once an act of reclamation—why should we remember this community only through the lens of what became of it?—and of realism: If the actual equivalents of the families in this book had seen what was coming for them, history would have unfolded quite differently. It may also be one of the reasons Grade’s work never hit it as big in the United States as that of his contemporary Isaac Bashevis Singer, who won the Nobel Prize and is widely considered the United States’ first great Jewish writer. Singer’s English was much better than Grade’s, which let him connect with his American audiences, and of course his wife didn’t sit on his papers for decades after he died—but also, Singer wrote frequently about the legacy of the Holocaust. He did so in a complicated and nuanced way—Enemies, a Love Story, his tale of a morally bankrupt, emotionally troubled survivor, is one of the slipperiest novels I’ve ever read—and yet, as Adam Kirsch writes in his introduction to Sons and Daughters, American readers who knew little about Judaism could “intuitively grasp” Singer’s portraits of Jews as victims of a horrible modernity. Grade’s characters, not fully victimized and not fully modern, presented far more of a challenge.

Sons and Daughters, after all its delays, now emerges into a United States in which Holocaust memory looks quite different than it did in the 1980s, when the English translation was initially meant to appear. Then, it would have been common for readers, depending on their demographics, to remember the war or to know Holocaust survivors, veterans who’d helped free them, or both. Now, this is much less true. High school and college students learn less and less about the Holocaust, and in literature, it has been transformed from the subject of painful spiritual investigation into—horrifyingly—a convenient and well-trod moral lesson trotted out in everything from young-adult novels about Christian children to romances set at Auschwitz. Sons and Daughters is a badly needed counterweight to these phenomena. In a sense, it’s also a balance to the inescapable fact that fewer and fewer of us know anyone who went through the Holocaust—which is also to say, anyone who remembers the society it destroyed. Grade’s loving reanimation of his “vanished world” hinges on his choice to keep the Nazis out of it. He brings it back as it was, and even the most thoroughly modern among us should be grateful for it.