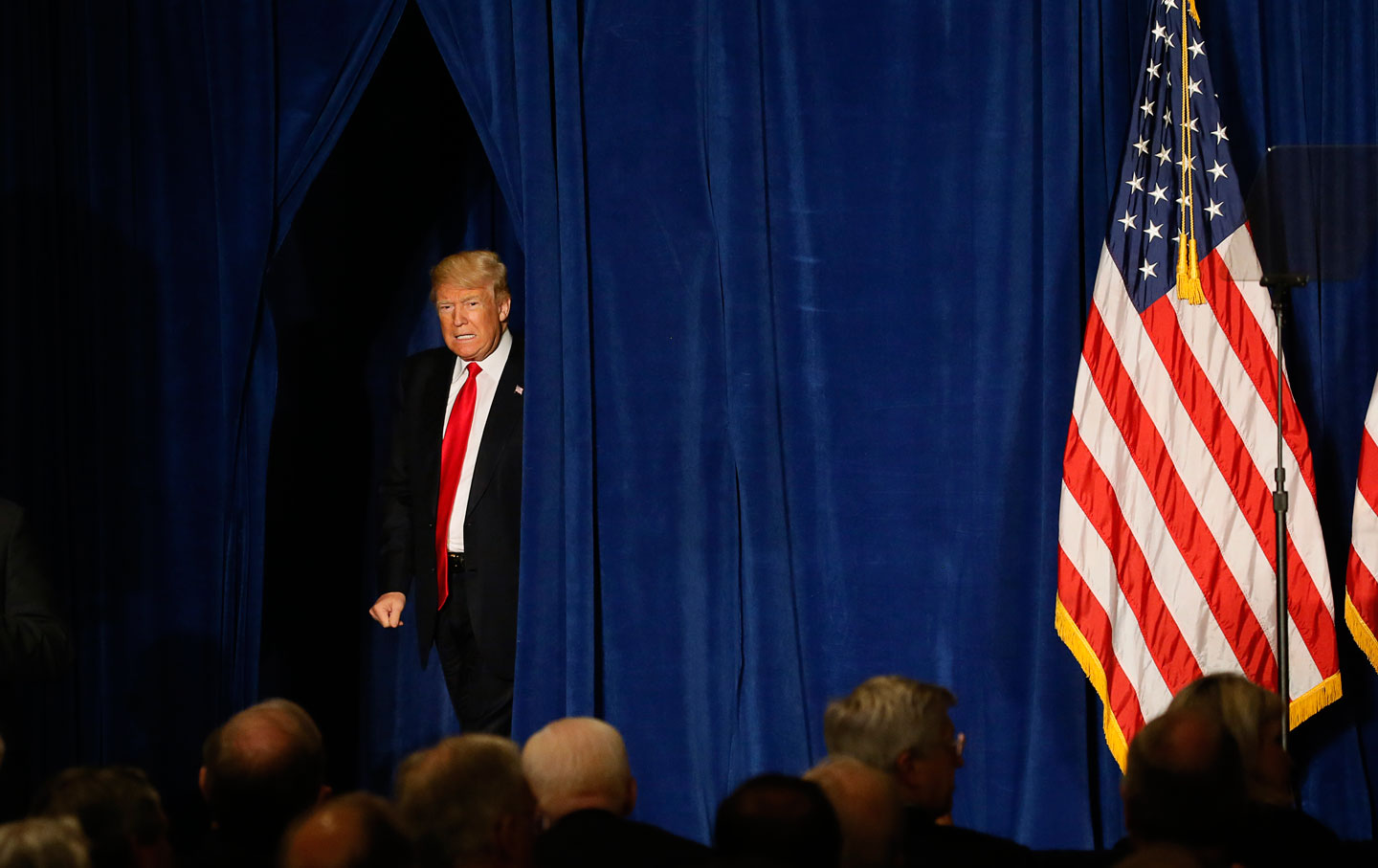

Donald Trump: The View From the Rust Belt Donald Trump: The View From the Rust Belt

Gary Younge on Indiana’s Trump supporters, Katha Pollitt on women voters, Tom Frank on e-mail leaks, and Adam Shatz on Obama, race, and racism

Nov 3, 2016 / Podcast / Start Making Sense and Jon Wiener

The Progressive Candidates Who Are Shaking Up This Election The Progressive Candidates Who Are Shaking Up This Election

John Nichols on the best candidates, plus Katrina vanden Heuvel on Tom Hayden, and the environmental journalist arrested for doing her job.

Oct 27, 2016 / Podcast / Start Making Sense and Jon Wiener

Donald Trump’s ‘Horrifying’ Refusal to Accept the Election Results Donald Trump’s ‘Horrifying’ Refusal to Accept the Election Results

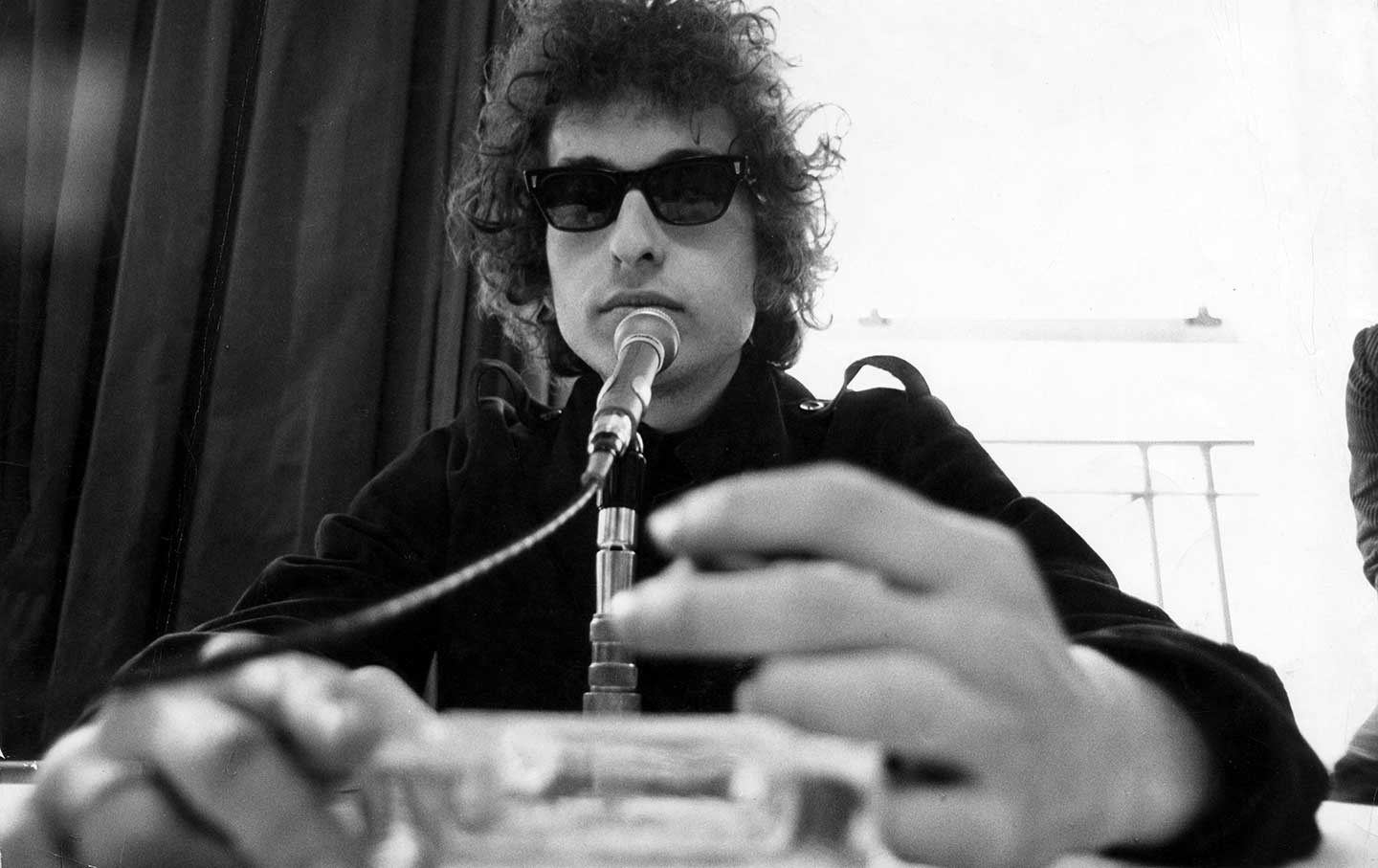

Joan Walsh on the debate, Kai Wright on right-wing media, and Greil Marcus on Bob Dylan.

Oct 20, 2016 / Podcast / Start Making Sense and Jon Wiener

Greil Marcus: Maybe Bob Dylan Isn’t a Poet, but He Is One of America’s Greatest Artists Greil Marcus: Maybe Bob Dylan Isn’t a Poet, but He Is One of America’s Greatest Artists

The music writer on how Dylan has changed his songs over the decades.

Oct 19, 2016 / Podcast / Start Making Sense and Jon Wiener

Donald Trump’s ‘Great Respect for Women’ Donald Trump’s ‘Great Respect for Women’

Katha Pollitt on Trump, D.D. Guttenplan on the campaigns in Ohio, and Gary Younge on children killed by guns.

Oct 13, 2016 / Podcast / Start Making Sense and Jon Wiener

Trump’s Economic Advisory Team Includes Just 1 Economics Professor Trump’s Economic Advisory Team Includes Just 1 Economics Professor

Who is Peter Navarro, and why don’t more academics support Trump?

Oct 11, 2016 / Jon Wiener

The First Republicans to Break With Trump Over His Groping Tape Were Mormons The First Republicans to Break With Trump Over His Groping Tape Were Mormons

Does this give Clinton a chance in Utah?

Oct 10, 2016 / Jon Wiener

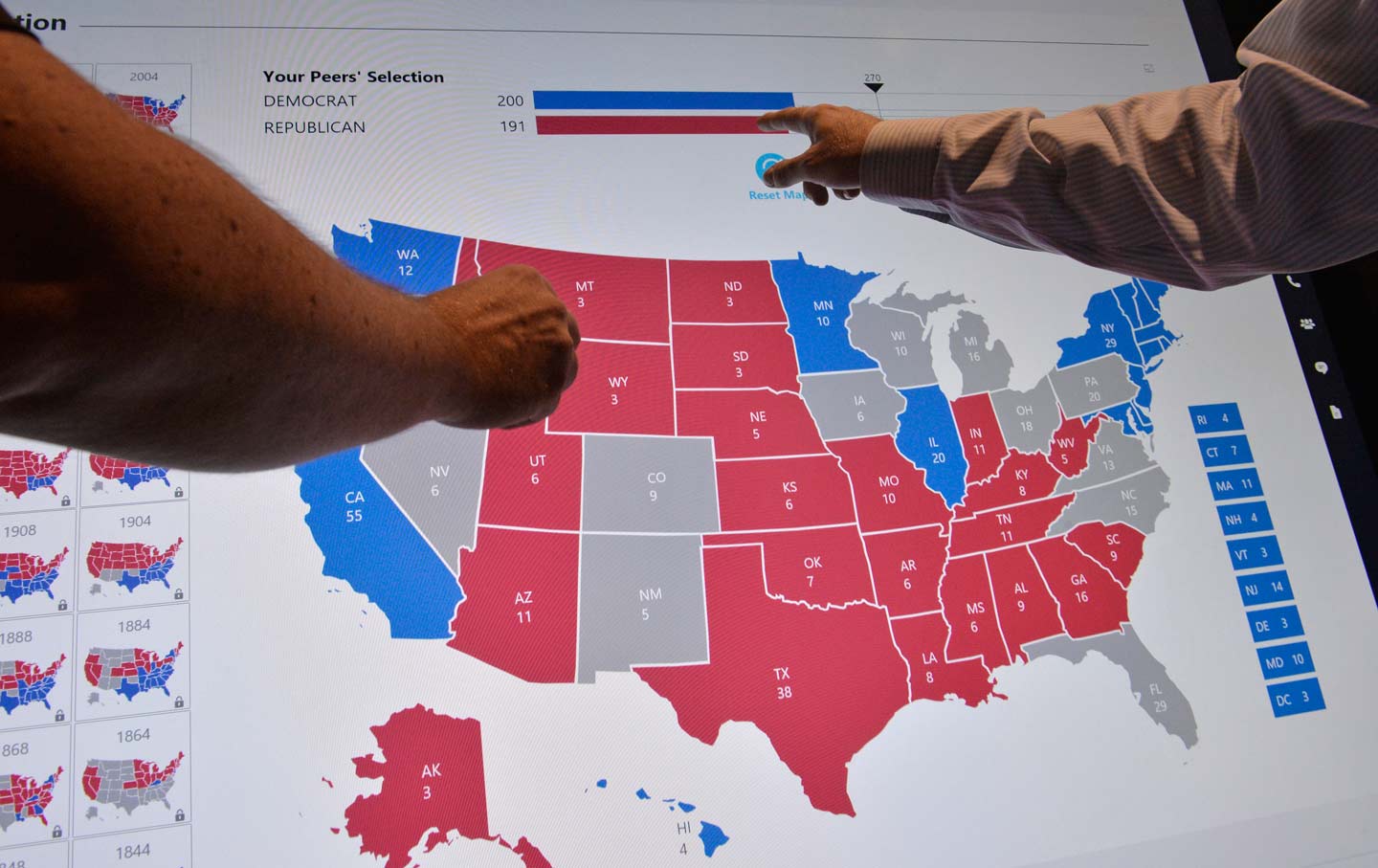

The Clinton-Trump Electoral Map Looks Almost Exactly Like the Obama-Romney Map. How Is That Possible? The Clinton-Trump Electoral Map Looks Almost Exactly Like the Obama-Romney Map. How Is That Possible?

We’ve never seen a presidential candidate like Trump before. Why does the electoral math seems so familiar?

Oct 7, 2016 / Jon Wiener

A Journey Into the Heart of Trump Country A Journey Into the Heart of Trump Country

Arlie Hochschild on her new book, plus Amy Wilentz on Trump’s high road and Robert Kenner and Eric Schlosser on Command and Control.

Oct 6, 2016 / Podcast / Start Making Sense and Jon Wiener

Katha Pollitt: It’s Time to Get Active for Hillary Katha Pollitt: It’s Time to Get Active for Hillary

Plus, Kai Wright on Trump’s supporters and D.D. Guttenplan on the British left.

Sep 29, 2016 / Start Making Sense and Jon Wiener