In April 1950, three months before Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were arrested as Soviet atomic spies, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover began chasing a bigger fish: the physics wunderkind Theodore Alvin Hall. Hired at 18 as a Harvard junior by the Manhattan Project, Hall arrived at Los Alamos on January 28, 1944, and learned he’d be helping to create an atomic bomb. Although the project was a response to fears that Germany might develop nuclear weapons, by that summer, with the German army in retreat, Hall grew concerned that the bomb’s real target would be the USSR, America’s wartime ally.

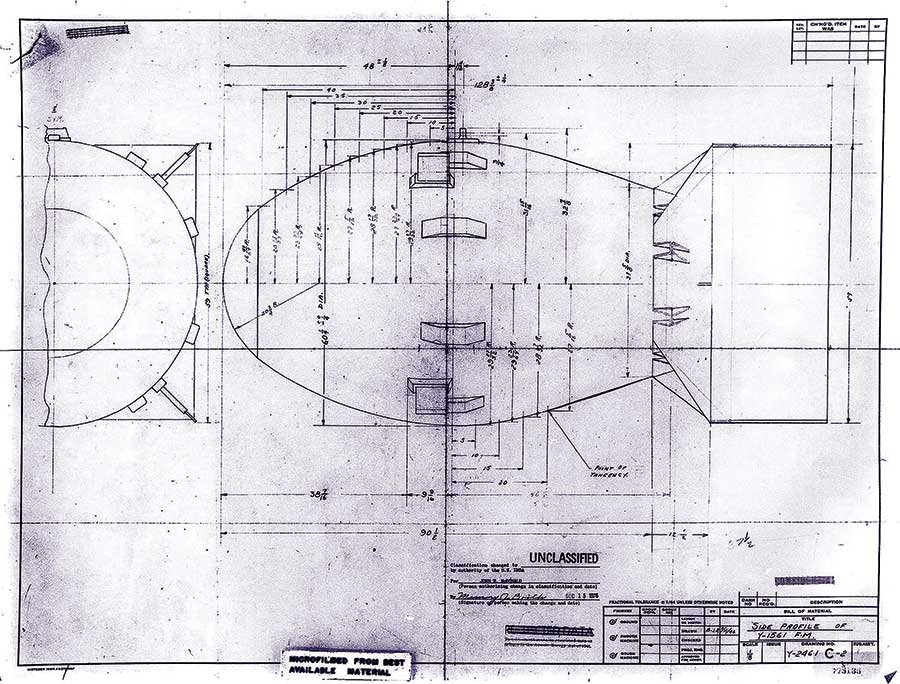

While still at Harvard and unaware what he was being recruited for, Hall and his friend and roommate Saville Sax (the only person he told about his new job) shared their concerns that the Soviet Union was being left out of what was clearly the development of some new weapon. When he learned that he was working on a bomb of unimaginable destructive power, Hall, like some other scientists on the project—notably Niels Bohr, Leo Szilard, and Joseph Rotblat—worried about what might happen if the United States ended up with a postwar monopoly on atomic bombs. Bohr urged President Franklin Roosevelt to share information about the project with the Soviets—and for his efforts had the FBI monitoring him. Rotblat, a Polish exile to Britain, quit the Manhattan Project over the issue of Soviet exclusion. Perhaps thanks to youthful impulsivity, Hall, in his discussions with Sax, arrived at a different and more treacherous solution: He would give the Soviets information about the implosion trigger he was working on, in the hope that the Soviets’ development of their own bomb would deter US use of the weapon.

By late October, on the pretext of joining his family for his 19th birthday, Hall went to New York City and met up with Sax to try and locate a Soviet agent. Each managed to find one, though the agents were skeptical until Hall showed them convincing information about the project. With Sax acting as courier, Hall immediately began providing crucial information.

Code-named Mlad (Russian for “young one”), Hall, the youngest scientist on the Manhattan Project, was the first Los Alamos spy to be identified in 1949 by the US Army’s Signal Intelligence Service in the intercepted and decrypted transmissions—later known as the Venona cables—sent between Soviet agents in the US and Moscow. Sax, code-named Star (Russian for “old one”), was also among the first to be identified.

Assigning FBI agents across the country to the case, Hoover quickly learned that the young spy, a child of Russian Jewish immigrants in New York, had been working since the war’s end on a doctorate in biophysics at the University of Chicago and had married in 1947. He also learned that Hall’s older brother, Air Force Maj. Edward Nathaniel Hall, was designing rocket engines for nuclear-capable missiles at a top secret facility on Wright-Patterson Air Force Base outside Dayton, Ohio.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Most historians of atomic spying have little to say about the incongruous careers of these two brothers—the teenage prodigy physicist/spy who helped create the plutonium bomb for the US and the USSR, and his older brother, a brilliant rocket scientist who developed the intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) that could deliver such bombs to the Soviet Union and other targets. Those who are aware of both men have long wondered how they remained at large during the 1950s Red Scare—a time when merely having relatives or friends in the Communist Party was enough to end a career—but have never found a compelling explanation. Now that story can finally be told, thanks to a 103-page FBI file on Ed Hall recently obtained by The Nation under the Freedom of Information Act.

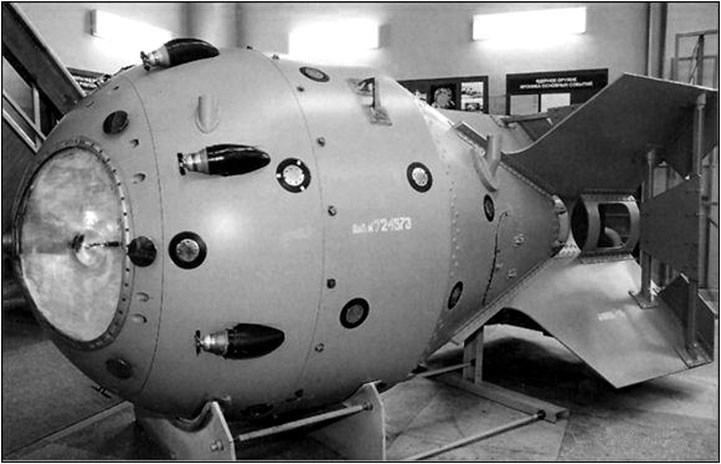

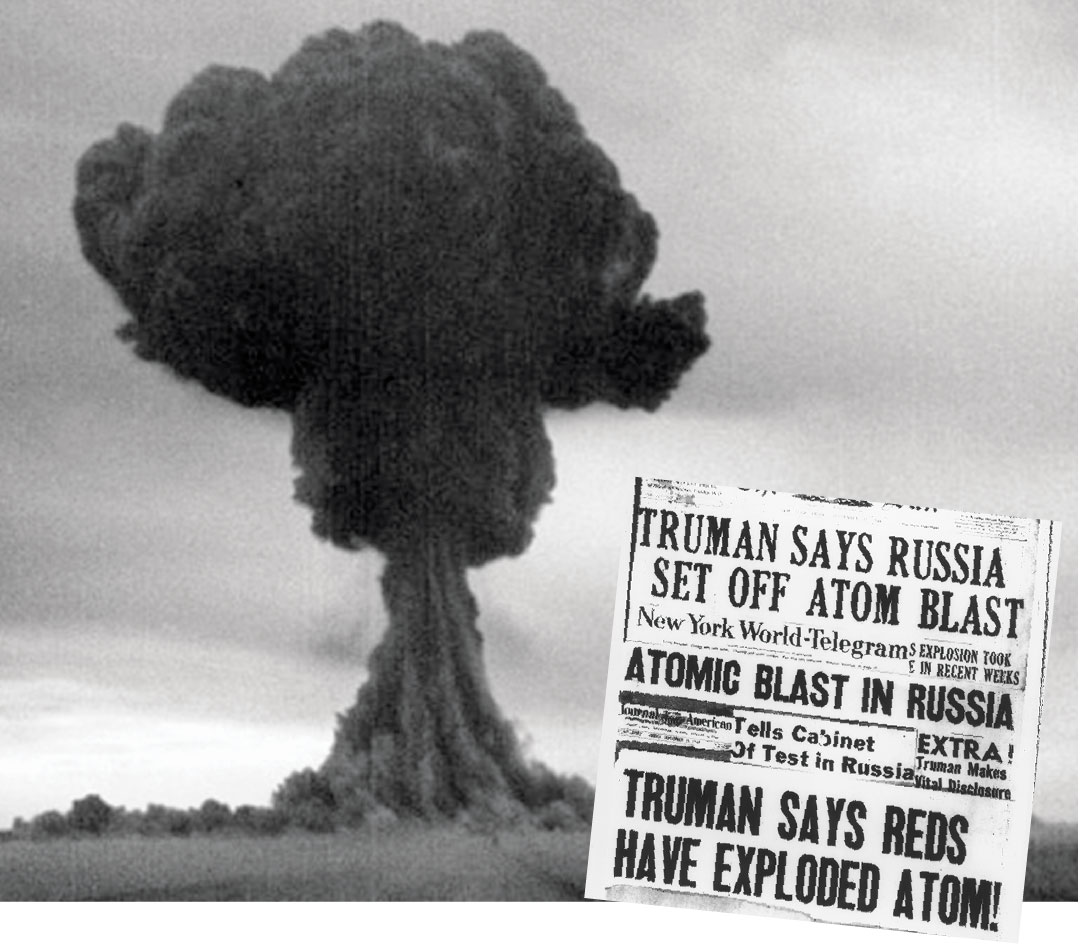

After World War II, paranoia about Soviet espionage became rampant in the US, stoked by government propaganda and later by the USSR’s surprise explosion—years ahead of US predictions—of its own atom bomb on August 29, 1949. With communism seemingly on the march in China, Eastern Europe, Korea, Vietnam, and elsewhere, it’s easy to imagine how badly Hoover, an obsessed anti-communist, must have wanted to nail this case.

By the end of 1950, at least one atomic spy—Klaus Fuchs, a fugitive Communist from Nazi Germany who became a Manhattan Project physicist and a leading Soviet spy—had confessed and been sentenced to 14 years in prison. Fuchs, however, had been captured by Britain’s MI5, not Hoover’s FBI. That summer, Hoover’s G-men had arrested a “ring of spies” headed by Julius Rosenberg, who would soon face trial along with his wife, Ethel, on capital espionage charges, but the doomed couple’s link to atomic secrets was minor. With Ted Hall, however, Hoover was closing in not just on a Los Alamos scientist but one whose brother—a Cal Tech aerospace engineer and officer in the Air Force—was known to be working on the development of top secret nuclear missiles.

After investigating both Hall brothers and Sax for over eight months—while keeping information about the case under tight wraps inside the bureau—Hoover decided it was time to alert the Air Force. After all, the Pentagon would have jurisdiction over investigating and court-martialing Major Hall—unless it decided to pass his case to the FBI.

Hoover sent a letter on January 6, 1951, to Gen. Joseph F. Carroll, commander of the Air Force’s Office of Special Investigations, which handled counterespionage. A working-class Irish Catholic kid from Chicago who’d worked his way through college and law school before joining the FBI in 1940, Carroll first caught Hoover’s attention by helping nab an escaped Chicago mob boss, Roger “Tough” Touhy. Before long he’d become a top Hoover aide. When Air Force Secretary Stuart Symington suggested Carroll for the OSI job, Hoover enthusiastically endorsed him.

In the letter to his former aide, Hoover wrote:

Dear General Carroll:

Transmitted herewith for your information is a memorandum concerning Major Edward Nathaniel Hall, ASN 0-434506…. Inquiry concerning Theodore Alvin Hall, brother of Major Hall…was instituted upon receipt of information from a highly confidential source of known reliability that Hall has been engaged in Soviet espionage activity….

Sincerely yours,

John Edgar Hoover

Director

Attached was an enclosure dated January 4 outlining the bureau’s information on Ted Hall. It concluded:

Investigation has disclosed that Theodore Alvin Hall is a brother of Major Edward Nathaniel Hall, ASN 0-434506. Major Hall, as of September 27, 1950, was assigned to the Power Plant Laboratory, Engineering Division, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Dayton, Ohio, and was reportedly working on a highly secret and confidential project.

The file doesn’t include Carroll’s response to what was surely shocking news from his former boss.

In response to a Freedom of Information Act request by The Nation, the Air Force’s OSI said it had no file on Ed Hall and no record of the correspondence of General Carroll, who in 1961 moved on to head the new Defense Intelligence Agency. (Carroll retired from the Air Force in 1969 and died in 1991.) Such files “may have existed,” I was told, but they “could have been destroyed as part of a routine records purge.”

There is, however, a second letter from Hoover to Carroll in the FBI’s Ed Hall file. In it, the director quotes from a letter of reply he received from Carroll. On March 27, 1951, Hoover (omitting any salutation this time) writes:

Reference is made to my letter dated Jan. 6, 1951…concerning Major Edward Nathaniel Hall…brother of Theodore Alvin Hall…the subject of a current espionage investigation by this Bureau. It is noted that in your letter dated January 18, 1951, concerning captioned individuals, you advised that a limited inquiry would be conducted by your Department to determine whether Major Hall engaged in activities inimical to the best interests of the United States.

Hoover writes that his agents had just interviewed Ted Hall, who “declared that he never furnished unauthorized information to anyone not entitled to receive it, and, furthermore, that he had never been approached by anyone, directly or indirectly, to furnish such information to unauthorized persons.” He also reports that the Chicago FBI office leading the Ted Hall investigation “has requested that Major Hall, a regular Air Force officer on duty at Wright-Patterson AFB, be interviewed re Theodore Hall, his younger brother.”

Hoover adds:

This Bureau’s investigation has now progressed to the point where interview of Major Hall concerning his brother, Theodore, is desirable…. Accordingly, it will be appreciated if you would advise at your earliest convenience whether you have any objection to an interview of Major Hall at this time by Bureau agents.

Hoover’s request to let federal agents interview Ed Hall was eventually granted, although General Carroll appeared in no hurry to accommodate the director. On June 12—11 weeks after Hoover’s urgent request—Cincinnati bureau agents finally got their interview, with an OSI officer observing. The agents’ report on that two-hour session, dated August 10, shows that the questioning, as promised by Hoover to Carroll, was largely limited to asking what Ed Hall knew of his brother’s actions. The report shows that he insisted he knew nothing about any spying by Ted. But that may not have been the whole story.

Asked last April when Ed Hall learned about his younger brother’s spying, Ted’s widow, Joan (now 92 and still living in the family home in Newnham, England, just outside Cambridge), suddenly recalled an incident she’d forgotten to mention in our prior conversations. On March 17, 1951, the Saturday morning after Ted and Sax had been interrogated separately and aggressively for three hours in the FBI’s Chicago office, she said, a man showed up at her and Ted’s Chicago home claiming to be a repairman sent to “fix” the phone (which wasn’t broken). Once he left, there was a second knock at the door; it was Ed, who, without calling ahead, had driven all night from Ohio. Checking the phone and signaling that he believed it was bugged, Ed indicated for Joan and Ted to join him outside. “OK, Ted, what kind of trouble did you get into this time?” he asked.

Joan recalled, “Ted sort of smiled and said he’d been questioned by the FBI about spying, and Ed responded that he’d also been questioned about Ted spying.” She added, “He didn’t ask Ted if it was true he was a Soviet spy. He just told him he’d been questioned and that he knew nothing about any spying.”

Following that brief exchange, the two brothers walked off together. They returned almost an hour later, after which Ed returned to Dayton. Though the two families often visited each other, the brothers supposedly never discussed Ted’s espionage again until 1995—after his role was revealed by the National Security Agency’s declassification of the decrypted Venona cables.

The questioning Ed referred to during his surprise visit was clearly by OSI agents, not the FBI, because Hoover’s letter to Carroll requesting permission to question the older Hall brother was dated March 27—10 days after Ed’s surprise visit. FBI agents didn’t interview Ed until nearly three months later.

The FBI report on that June 12 interview shows that Ed didn’t disclose his March 17 visit, claiming his last visit to Ted had occurred a year earlier, in March 1950.

According to his FBI file, Ed was interviewed four times by the OSI and once by the FBI. In his FBI interview, Ed explained that he hadn’t seen his brother during the war years, as Ed had been stationed in the United Kingdom, and that after the war he’d seen him only a few times. Admitting that he’d been very close to Ted when they were young, Ed said that following his 1939 enlistment in the military he’d been posted far from New York, Boston, and Los Alamos—and that since the war, the two brothers had “not been particularly close.”

That was simply a lie, Joan told me when I showed her the report. “They were always extremely close.”

The FBI report also indicates that the agents, while assuring Ed they were “not associating [him] with any responsibility for Theodore’s actions,” did warn him that, given his plans for an Air Force career, his brother’s refusal to cooperate with FBI investigators was “a matter in which he might have considerable concern.”

Following this veiled threat, the agents refused to offer Ed any specific advice or instruction. “After some study,” the report notes, he promised to make another trip to Chicago on June 22. What he actually advised Ted to do isn’t known, but the agents’ report says that Ed claimed he’d failed to persuade his brother to cooperate, adding that Ted complained that the agents wanted him to reveal the names of Progressive Party and leftist activists, something he wouldn’t do.

That June interview concluded the FBI’s efforts to interrogate not just Ed but Ted and Sax, too. Hoover likely still harbored suspicions about Ed, but General Carroll didn’t. In what must have felt like a thumb in the eye to Carroll’s former boss, the Air Force promptly promoted Ed and made him deputy chief of the rockets and ramjets Power Plant Lab. By August 10, the agents’ report refers to Ed as “Lt. Col. Hall.” By October 25, the OSI had formally concluded its loyalty inquiry. The following February the FBI effectively dropped its investigation of Ted Hall and Sax entirely, moving both from its Special Section Security Index to the Regular Section, meaning that constant monitoring, mail interception, phone taps, etc., ended for both men. A memo in the file from the Chicago office announcing the closure of the active case involving Ted includes the letters “UACB” (for “unless advised to the contrary by the bureau”) after the term “Regular Section.”

In 1954—amid Senator Joseph McCarthy’s controversial televised hearings intended to expose Communist infiltration in the Armed Forces—Ed Hall was named director of the entire US ballistic missile development program, a position he held until his retirement from the Air Force in 1959. In 1957, he was promoted to full colonel. Recognized as the lead developer of engines for the Atlas and Titan ICBMs in his Air Force biography, perhaps more significantly, Ed created the Minuteman solid-fuel instant-launch ICBM concept, as well as the Minuteman I itself. In 1999, the year Ted died and seven years before his own death at 91, Ed Hall was inducted into the Air Force Space and Missile Hall of Fame.

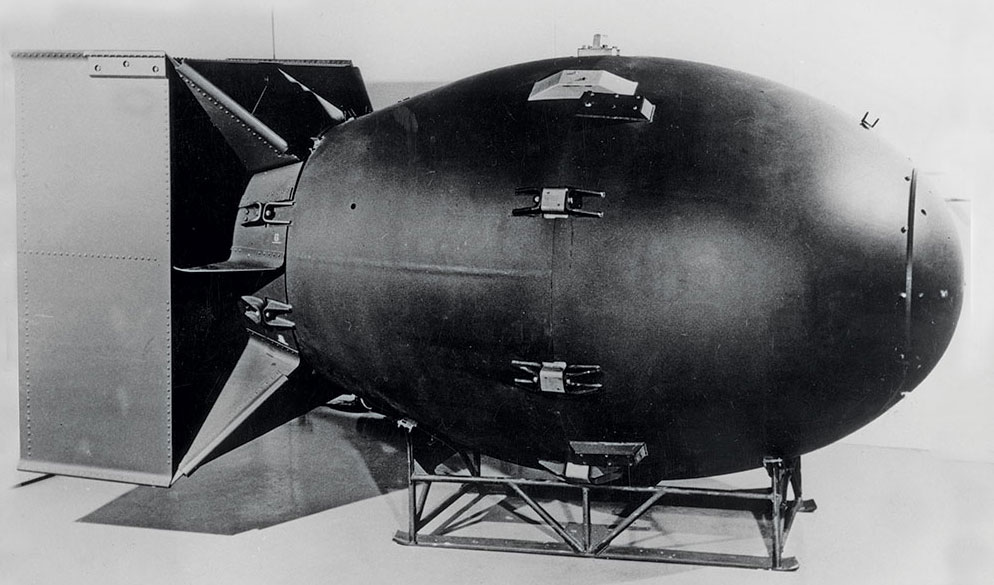

Most historians of atomic spying have paid scant attention to Ted Hall. His Los Alamos ID photo—showing a pimply, stone-faced teenager—is often included in atomic spy lineups, but information about what he actually did is limited to a few lines or a footnote. The one exception is Bombshell, by Joseph Albright and Marcia Kunstel, which focuses on Ted’s story. Published in 1997 (before key FBI files were available), the book details how Ted’s information about the plutonium bomb’s implosion trigger filled critical gaps in the information provided by master spy Fuchs. Though unknown to each other, the two spies provided the Soviets complete (and, coming from two separate sources, more credible) plans for the bombs detonated at Alamogordo in New Mexico and at Nagasaki, advancing the USSR’s acquisition of its own bomb by two to five years, according to Albright and Kunstel.

“I find it baffling that there was no continued surveillance by the FBI of both Ted and Ed Hall through the 1950s,” said Peter Kuznick, a professor of history and the director of the Nuclear Studies Institute at American University. “Certainly the FBI could have continued to keep an eye on them.”

The explanations offered by FBI officials and some Cold War historians for why Ted escaped prosecution—that the FBI didn’t want to reveal that the US had broken the Soviets’ spy code, and that without such evidence or a confession, it would have been unable to convict or even indict him—aren’t convincing.

“Look how they handled that issue with Julius Rosenberg,” said Kuznick, noting that key evidence in the Rosenberg case came from the Venona decrypts—a fact that remained secret for decades after the couple’s execution. “They just indicted Ethel too, to try and get him to confess. It didn’t work in that case, but they could certainly have indicted Ted’s wife as a coconspirator to get a confession from him.” He added that prosecutors could also have piled other charges on Ted and Sax—such as lying to the FBI—avoiding the need to rely on the Venona material.

Besides, the Soviets already knew that their code had been cracked thanks to a spy named William Weisband, who worked as a translator inside Arlington Hall, the Virginia complex where the decryption process was carried out. By 1950, Weisband—who failed to respond to a summons to appear before a grand jury investigating Communist activity—had been convicted of contempt and sentenced to a year in prison.

A more likely explanation for Ted’s escape was the message sent indirectly by the Air Force in the form of the rank and job promotions his brother Ed received so soon after his June 12 Cincinnati FBI interview.

Ed clearly was considered vital to the US ballistic missile program (which at the time was seen as lagging behind the Soviet effort). And as Kuznick noted, “If Ed was viewed as critical to the missile program, certainly the FBI couldn’t have been allowed to arrest his brother as a Soviet spy because, especially in the 1950s, that would have made Ed radioactive no matter how confident the Air Force and the OSI’s General Carroll were [of Ed’s] loyalty.”

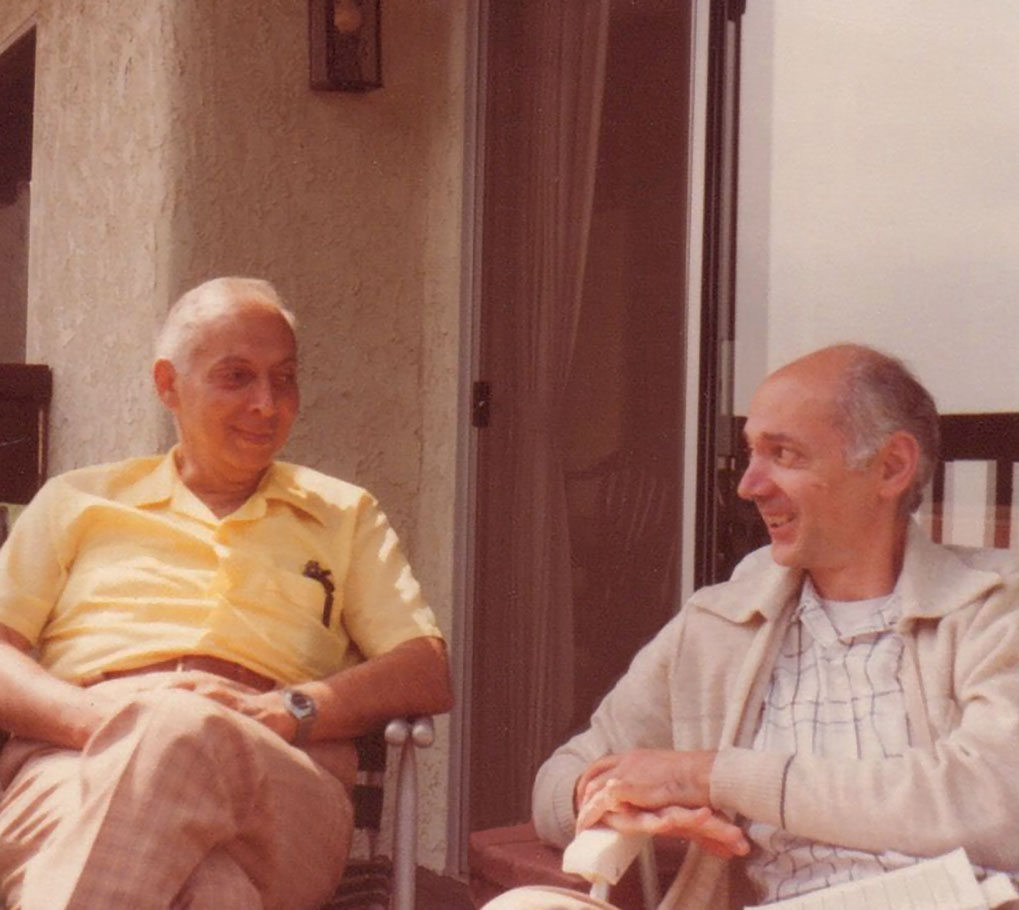

Ed and Ted Hall remain a fascinating pair—both brilliant and fiercely loyal to each other, but with very different personalities. Ed, Ted’s senior by 11 years, told their parents (neither of whom were college-educated) when Ted was 4 that he was “taking over” his brother’s education. And he did, introducing his precocious charge to advanced algebra in grade school and enrolling him in his alma mater, Townsend Harris High School, a New York City public school famed as an “incubator” of geniuses. Ed encouraged Ted to attend Queens College at 14, and later, writing from the UK, suggested that his brother transfer to Harvard (as a junior physics major) at 17 in 1943. Ed had earned a BS in engineering and a professional degree in chemical engineering from the City College of New York and then an MS in aeronautical engineering from the California Institute of Technology. Enlisting in the military in 1939, he spent his war years in the UK repairing damaged bombers. After Germany’s surrender, he joined the Army’s Special Forces as a rocket expert in a program whose mission was to grab whatever could be had of Germany’s V-2 and other advanced weapons.

While Ed may have helped round up Nazi rocket scientists as part of Operation Overcast (later Paperclip), it is documented that on one daring late-1945 foray deep into Soviet-occupied eastern Germany, he oversaw the destruction of a V-2 engine factory at Nordhausen. Throughout his military career Ed received a Bronze Star and at least four Legion of Merit awards.

His younger brother followed a different path. In 1962, both to escape the oppressive anti-communist political environment in the US and to avoid further FBI attention, Ted accepted a position in biophysics at Cambridge University’s Cavendish Lab, where he worked until his retirement in the mid-’80s.

He didn’t entirely escape investigation, though. While renewing his work visa in 1963, Ted was contacted by an agent of MI5, who suggested he “ease his conscience” by confessing to spying. He spurned this “offer,” and MI5 interest evaporated. Unknown to Ted, in 1966 Boston FBI agents quizzed the Harvard physicist Roy Glauber. In 1944, Ted had told Glauber, a former classmate and roommate who was hired with him to work at Los Alamos, that he’d met with a Soviet agent. Protecting his old college friend, Glauber denied any knowledge of Ted’s spying. That ended Hoover’s last effort to nail Ted Hall.

Did the Air Force OSI shut Hoover down for over a decade? General Carroll’s son James, a former columnist at The Boston Globe, thinks that’s quite likely. “My dad revered Hoover,” he told The Nation, “but he was someone who wouldn’t have hesitated to stiff-arm him if he thought he was interfering with the prerogatives of the Air Force or OSI.”

Whatever Hoover’s reason for halting the pursuit, no word concerning the two brothers—or Ted’s spying—leaked to the media until 1995, when the NSA declassified the Venona cables.

At Ted Hall’s Cambridge remembrance service, fellow physicist Mick Brown called him “a living example of selfless courage, and a hero to the present young generation of science students.” That may seem an odd way to describe someone who, whatever his reasons, abetted nuclear proliferation.

However, considering America’s murderous history since the end of World War II, it seems likely that had the Soviet Union not obtained the bomb when it did, the US might well have stopped at nothing—including a nuclear strike—to defend its atomic monopoly. Indeed, recently declassified Pentagon and national security documents show that in the late ’40s there were serious plans for a preemptive blitz on the USSR using the hundreds of nuclear weapons the US would have manufactured by 1951—plans thwarted by the Soviets’ surprisingly early development of the bomb.

Ted’s assumption that an atomic standoff between the United States and the USSR would lead to a ban on nuclear weapons (as occurred with germ and chemical weapons) proved to be mistaken. Instead, the Soviets’ acquisition of the bomb led to a costly arms race, which now appears to be ramping up again. Nightmarish as that reality has been, it has also produced an astonishing 77 years (and counting) of no nuclear weapon being used since Nagasaki.

At least some of the credit for that belongs to the Hall brothers.

Correction: A previous version of this article stated that Townsend Harris High School was located in Brooklyn during the time of the Halls’ attendance. In the 1930s, when they attended, the campus was actually located in Manhattan.