Report From the Progressive International’s Nuestra Summit

Colombia holds its breath as President Gustavo Petro heads to DC.

Bogotá— “Don’t go!” more than one voice could be heard shouting in the packed Teatro Colón on January 24. The plea was in response to Colombian senator María José Pizarro Rodríguez’s declaration that Colombia’s President Gustavo Petro would be traveling to the White House on February 3 “in an act of courage.” While the popular Pacto Histórico senator was mostly met with cheers and chants of the Chilean protest song, “El pueblo unido jamás será vencido,” the mixed response captures the overwhelming uneasiness in Colombia as their leader prepares to visit a country that mere weeks ago kidnapped Nicolás Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores, from the presidential palace in neighboring Venezuela.

“The bombing of Caracas made the threat of military intervention in Colombia feel more materially possible than we’d ever imagined,” Esteban Romero, a 27-year-old political scientist and local activist, told The Nation.

Pizarro spoke as part of the Progressive International’s “Nuestra América” summit during which 90 delegates from 20 countries discussed the Trump administration’s increasingly belligerent threats to a region treated as the United States’ “backyard” since the original Monroe Doctrine was issued. A slew of other high-ranking Colombian government officials, including Foreign Minister Rosa Villavicencio, hosted Progressive International delegates at the San Carlos Palace, sending the clear message that the Colombian left is taking a leading role in responding to the “Donroe Doctrine” or “Trump corollary” to the 1823 text that has justified two centuries of US interventionism. The summit was a rare show of international left solidarity and a resounding condemnation of Trump’s violations of international law at a time in which American politicians and media have been reluctant, at best, to censure the president’s imperialist machinations.

“Latin America has decades of individuals and organizations that have directly confronted US imperialism,” PI delegate and former US Green Party vice presidential Candidate Ajamu Baraka, who now lives in the Colombian city of Cali, told The Nation. “People here are prepared to resist and to struggle.”

The summit was notably well-attended by a number of progressives from both the Global North and South, despite being organized at short notice after the attack on Venezuelan soil. Other Nuestra América delegates included former mayor of New York City Bill de Blasio, Vice President of the French National Assembly Clémence Guetté, Uruguayan Senator Bettiana Díaz, Cuban Ambassador Carlos de Céspedes, Venezuelan Ambassador Carlos Eduardo Martinez Mendoza, and British Member of Parliament Zarah Sultana, several of whom drew parallels between Venezuela and the ongoing genocide in Gaza. Petro himself had presaged this connection in his United Nations General Assembly speech last year, declaring, “What is being done in Gaza is an experiment to tell all the peoples of the world…they will be treated like this.” Although the Colombian president did not attend public events during the two-day summit, he met with a group of PI delegates before they issued their January 25 San Carlos Declaration pledging to “advance solidarity and affirm sovereignty across the hemisphere.” The Summit also featured discussions for a Caribbean solidarity flotilla based on the Sumud Flotilla that has sent several boats filled with activists and supplies to Palestine. Underlying the summit, there seemed to be a growing sentiment that Trump’s threats are reinvigorating the global left as his most egregious actions highlight the urgent need for a strong alternative that many liberals seem incapable of providing.

Though tensions had come to head between the Colombian and US presidents in the new year, the conflict between the two had been mounting long before the US attack on Latin American soil that inspired the summit. A year earlier, in January 2025, Trump threatened to impose a 25 percent tariff on Colombian goods when Petro initially refused to accept military planes carrying deported Colombian citizens. In September, the US government “decertified” Colombia, directly blaming the “incompetence of Gustavo Petro and his inner circle” for a rise in coca-growing operations in the South American country, but issued a waiver for the country to continue receiving US aid.

That same month, after Petro addressed pro-Palestine protesters during the UN general assembly, and told US soldiers “not to point their guns at people. Disobey the orders of Trump. Obey the orders of humanity,” the State Department revoked his visa. Then, in a further escalation, the US Treasury slapped sanctions on the Colombian president, his wife and eldest son, as well as Colombian Interior Minister Armando Benedetti, over unsubstantiated claims about their “involvement in the global illicit drug trade” shortly after Petro accused Trump of “murder” over the Caribbean boat bombings that killed at least one Colombian citizen.

When the United States bombed Caracas, killing 100 people, according to Venezuela’s interior minister, and imprisoned the Venezuelan president in New York, it seemed as if Colombia and the US suddenly could be headed toward their own bloody confrontation. Petro took to X on January 4 to harshly condemn his American counterpart’s actions, writing, “Without a legal basis for taking action against Venezuela’s sovereignty, the detention becomes kidnapping.” He then went so far as to add, “I know perfectly well that what Donald Trump has done is abhorrent. They have destroyed the rule of law worldwide. They have bloodily urinated on the sacred sovereignty of all of Latin America and the Caribbean.”

The very same day, Trump told reporters, “Colombia is very sick too, run by a sick man who likes making cocaine and selling it to the United States. And he’s not going to be doing it very long, let me tell you.” He added that military action against Colombia “sounds good to me,” and that Petro should “watch his ass.” As Petro sent troops to the 1,379-mile border Colombia shares with Venezuela, the Colombian president, a former M-19 guerrilla who’d once helped steal Simon Bolivar’s sword from the Quinta de Bolívar museum in Bogotá, called on his supporters to take to the streets to protest the US, and announced on X that, although “I swore not to touch a weapon again…for the homeland I will take up arms again.”

“Petro had a realistic and not unfounded fear he could be ‘next,’” Cynthia Arnson, adjunct professor at Johns Hopkins University and an expert on Colombia-US relations, told The Nation. “He had been sanctioned by the Office of Foreign Assets Control as a narco trafficker—which I think is an erroneous designation of Petro himself—but it was entirely conceivable that the Trump administration would stage an operation to capture him as he had Maduro.”

On January 7, 20,000 of the left-wing president’s followers answered his call, filling the capital’s Plaza de Bolívar to show their support for his imperiled leadership along with thousands more in cities and towns across the country. But much to everyone’s surprise, something of a Hail Mary bore fruit: The two leaders got on the phone to speak with each other for the very first time. The phone call, initiated by the Colombian government and facilitated by the US embassy and Kentucky Senator Rand Paul, lasted an hour, after which Petro finally came out to address his followers in Colombia’s capital amid rain, anticipation, and more than a little confusion. Petro explained that, although he’d previously written a fiery speech, he’d had to tone it down to sound less “harsh” after his call with Trump. Even so, he gave a promise: “To the mothers of Colombia, I say that the country clearly stands up for the defense of national sovereignty.… If they touch Petro, they touch Colombia. And if they touch Colombia, Colombia responds as its history has taught it—plain and simple.”

Soon after Petro’s televised speech, Trump wrote on Truth Social, “It was a great Honor to speak with the President of Colombia, Gustavo Petro, who called to explain the situation of drugs and other disagreements that we had. I appreciated his call and tone, and look forward to meeting him in the near future. Arrangements are being made between Secretary of State Marco Rubio and the Foreign Minister of Colombia. This meeting will take place in the White House in Washington, D.C.”

Romero, who had taken to the streets of Medellín that Wednesday night with thousands of his compatriots, expressed his hope that the White House meeting would “de-tense” a country that has been on edge for months.

In a number of international media interviews held after the call, Petro explained that he spoke for 45 minutes on a number of issues he found relevant to the relationship between the two countries, while Trump responded for 15 minutes, saying that he had been considering doing “something bad” in Colombia but understood that “a lot of lies” had been said about both of them. In the days and weeks that have followed, everything seems to indicate that the meeting between the two leaders will take place on February 3 at the White House, with Secretary of State Marco Rubio and Foreign Minister Villavicencio making arrangements for the visit, including obtaining temporary five-day visas to the US for President Petro and Villavicencio.

The meeting that has many Colombians feeling uneasy is being held during a clear boiling point between the two social media–obsessed presidents and, by extension, between the two countries.

“I’m anxious about the president’s safety,” says Yara Ruiz, a 29-year-old audiovisual producer from Bogotá, “but, it’s also a relief that they’ll have dialogue. Petro clearly wants Colombia to feel calmer about a looming US threat.”

Despite the rhetorical clashes that characterized the past year, both governments have been striking a notably conciliatory tone, stating that on February 3 they’ll “pivot from recent tensions toward ‘common priorities,’ including trade, joint economic opportunities, and regional security [as well as] intensifying the fight against transnational organized crime,” according to the Associated Press.

“The issue of drug trafficking will be front and center,” predicts Arnson. “The Trump administration will likely push for a much more robust effort at eradicating coca cultivation. There is also the issue of the National Liberation Army (ELN): its presence in Venezuela and virtual control of the Colombian Venezuelan border.”

According to the United Nations, “potential cocaine production increased by 53 per cent” under Petro’s watch, but both the Colombian national police’s anti-narcotics directorate and the US Drug Enforcement Administration recently told CNN that they continue to work closely together, leading to “record drug seizures and increased pressure on cocaine producers and trafficking organizations” in recent years. Less than a week before the highly anticipated White House meeting, news broke that Colombian security forces killed five members of the Gulf Clan, a top cocaine cartel. As for the ELN, the Latin American guerrilla group’s increased activities are seen as a result of the failure of one of Petro’s key policies, Paz Total or Total Peace, which sought to finally put an end to Colombia’s six decades of war by bringing all remaining guerrillas to the negotiating table.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The tête-à-tête also comes at a critical moment in Colombian politics. The country’s first left-wing leader is entering the final months of his historic presidency and Colombians are heading to the polls to choose his successor beginning in March. With the far right on the heels of Pacto Histórico’s presidential candidate Ivan Cepeda, the party’s difficult nearly four years in power have come under scrutiny. Indeed, Petro’s tenure has been marked by both impressive gains—including a 23 percent increase in the minimum wage, long-sought-after agrarian reforms, and an impressive decrease in poverty rates—as well as troubling setbacks, like the virtual collapse of the Total Peace negotiations amid growing public concern over security issues.

In December, the president’s approval ratings plummeted to 29 percent, but just a month later, a poll showed that Petro had once again reached a high of 48 percent—possibly buoyed by his handling of the Trump administration’s threats. The president and his party still have many staunch supporters throughout the country, especially in the historically deprived coastal areas and large cities like Bogotá and Cali—with one young man even describing him to me as “Petro, my love.” However, in much of central Colombia, like in the notoriously conservative city of Medellín, where he won only 34 percent of the vote in the 2022 presidential election, several people expressed their desire that Petro be “taken” by Trump like Maduro. Though alarming, it’s perhaps not an entirely surprising sentiment in a country where the left has long been vilified, in part because of the bloody, seemingly endless conflict between guerrillas, paramilitary groups, narcotraffickers, and the state—a history that is certain to continue to play out in the upcoming election. Despite the odds, Cepeda has also risen in the polls recently, with surveys showing him beating all of the largely right-wing candidates in the first round—including the far-right Abelardo de la Espriella, who has professed his admiration for Argentina’s “El Loco” Javier Milei.

Beyond whether the left party’s record or Petro and his would-be successor’s popularity will be enough to keep the far right out of the Casa de Nariño, something else is worrying Colombians across the political spectrum.

“I think Trump will try to tip the scales in favor of the right in the upcoming elections like he did in Honduras,” said former director of the Medellín newspaper El Mundo Luz María Tobón. Tobón is referring to Trump’s promise during the Honduran presidential election that if his preferred candidate, Nasry “Tito” Asfura, won, “he would not only support the country economically but would also grant a ‘full and complete’ pardon to former Honduran president Juan Orlando Hernandez,” who was convicted in 2024 by a New York court for drug trafficking offenses.

Petro’s education minister, Daniel Rojas, who also participated in the Nuestra América summit, was more unequivocal about his concerns: “Trump has said his candidate has won in Argentina; his candidate has won in Chile—he appropriates them even—and I don’t think Colombia will be an exception on his Latin American electoral agenda,” he told The Nation. It might just be, however, if the positive polls for Cepeda are anything to go on, that Trump’s threats are actually having the opposite effect on a Colombian public who Pizarro promised would never “kneel” before the US empire. When asked why Trump has Colombia in his sights, the 38-year-old Rojas argued that it’s “not just because of Colombia’s geographic location, but because of its rich natural resources,” adding that the country is also a thorn in the side of the White House’s imperialist plans in the hemisphere.

Petro stepped back into the limelight on Tuesday after a quiet few weeks to show his “thornier” side and call for the United States to release the “kidnapped” Maduro so he can be tried in a Venezuelan court. As for his upcoming meeting with his US counterpart, the Colombian leader declared from the Casa de Nariño that it would be “key,” as it would determine “the life of humanity.” Though it wasn’t clear what he meant by the somewhat hyperbolic proclamation, for many across the country and the continent anxious about the “Donroe Doctrine” and its powerful, erratic author, the stakes likely feel just as high.

More from The Nation

There Is No “After Gaza” There Is No “After Gaza”

Whether intentionally or with callous word choice, too many have begun relegating Palestine to the past tense.

Cuba Rallies Residents, Prepares for War Cuba Rallies Residents, Prepares for War

As Washington escalates regime-change pressure after the Venezuela raid, Cuba braces for confrontation amid economic collapse, oil shortages, and mass mobilization.

Jared Kushner’s “Plan” for Gaza Is an Abomination Jared Kushner’s “Plan” for Gaza Is an Abomination

Kushner is pitching a “new,” gleaming resort hub. But scratch the surface, and you find nothing less than a blueprint for ethnic cleansing.

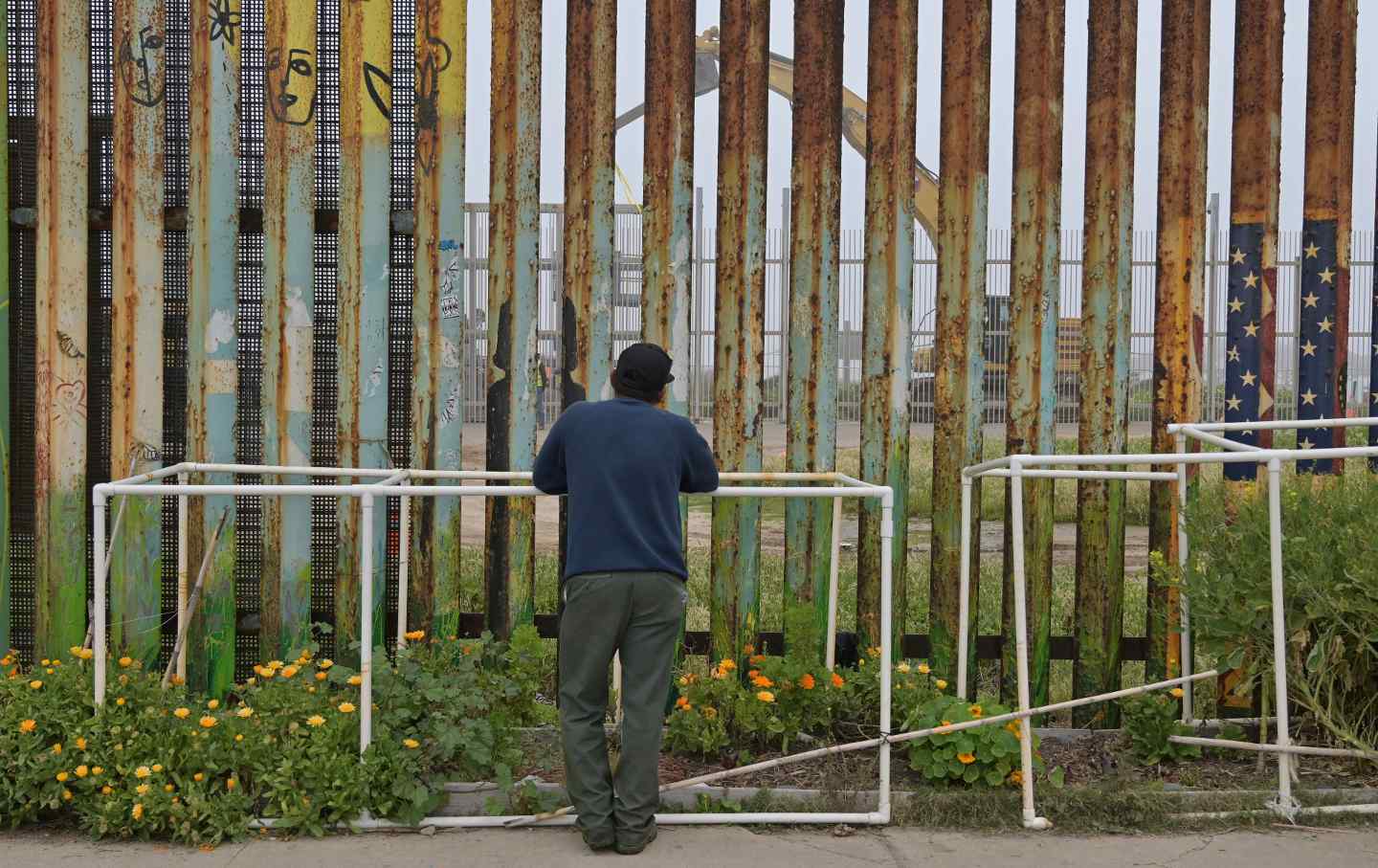

I’ve Covered Migration and Borders for Years. This Is What I’ve Learned. I’ve Covered Migration and Borders for Years. This Is What I’ve Learned.

Borders are both crime scenes and crimes, with nationalism the motive.

Gaza Is a Crime Scene, Not a Real Estate Opportunity Gaza Is a Crime Scene, Not a Real Estate Opportunity

The Trump administration’s plan for a New Gaza has nothing to do with peace and rebuilding, and everything to do with erasure.