“Whose Streets? Our Streets!”: Grants Pass v. The People

It’s past time for us to declare as a nation that our people are not disposable.

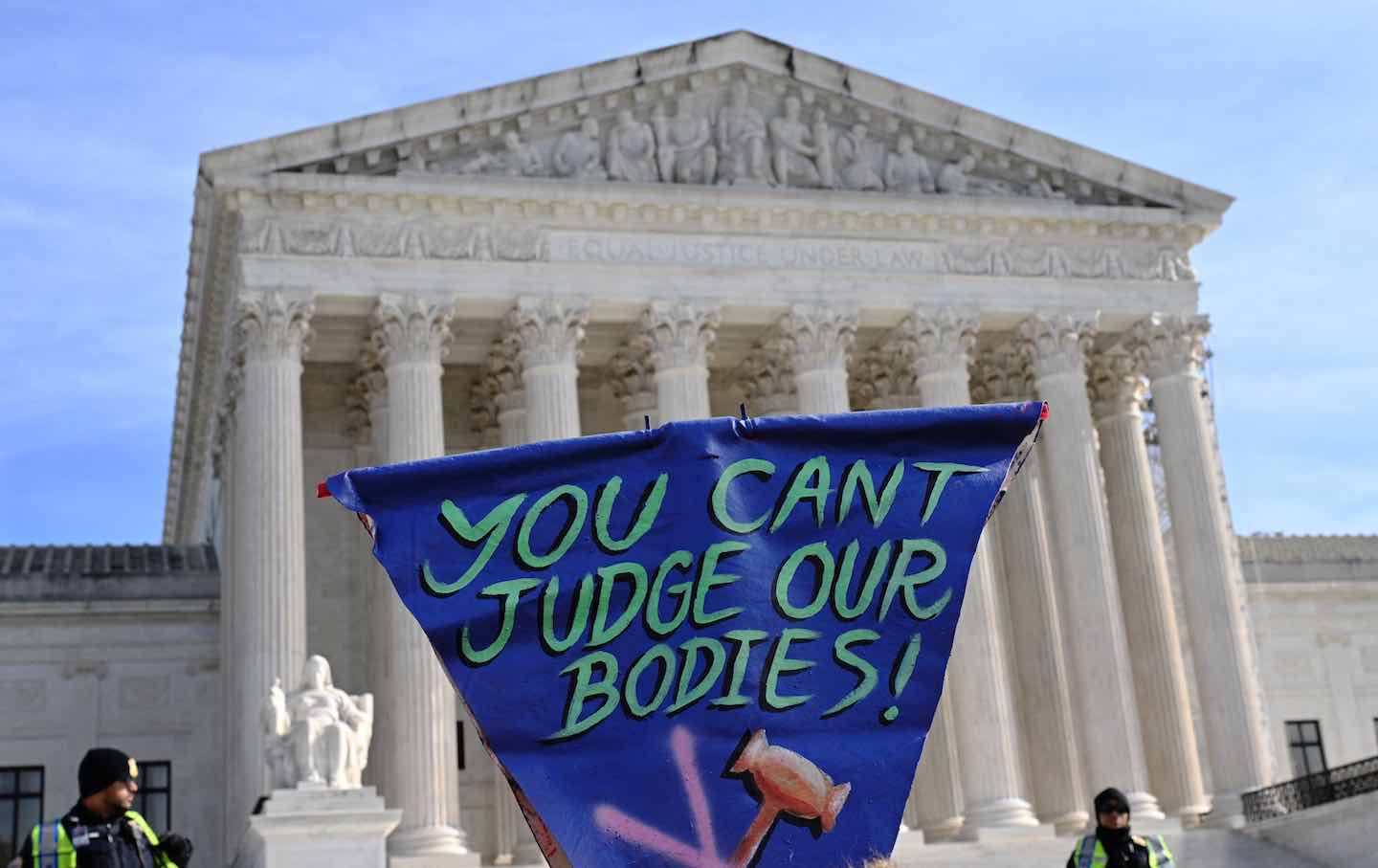

Homeless rights activists hold a rally outside the US Supreme Court Building on April 22, 2024, in Washington, DC. The Supreme Court heard oral arguments in City of Grants Pass, Oregon v. Johnson, a dispute over the constitutionality of ordinances that bar people who are homeless from camping on city streets.

(Photo by Kevin Dietsch / Getty Images)

On April 22, 2024, tens of thousands of people marched on city streets nationwide, rallying for a stop to the unconstitutional criminalization of unhoused people and an investment in real solutions to ending homelessness. Advocates, organizers, and people with lived experience had been planning their marches to coincide with oral arguments in the Supreme Court case Grants Pass v. Johnson, the first case at the high court to address homelessness in over 40 years. Included in the protesters’ chants was the call and answer, “Whose streets? Our streets!” This is a call that we have chanted multiple times.

For decades, this chant has served as a rallying cry for housing justice advocates, among others fighting for civil and human rights. As a formerly unhoused sitting member of Congress and cochair of the Congressional Caucus on Homelessness (Representative Cori Bush), and as a professor, activist, and thought leader in the fight for housing justice (professor Stephanie Sena), we understand both the stakes of this case and seek to defend the rights and lives of our unhoused neighbors nationwide.

The Supreme Court is currently grappling with the question of to whom the streets belong. The Oregon city of Grants Pass has asked the court if it has the right to ban people from sleeping in public, even when no shelter space is available.

The court—and our country—would do well to remember the nation’s long history of displacing communities, particularly marginalized communities, from public places and already vulnerable populations more at risk.

We are a nation that displaced Indigenous people from their ancestral lands and forced them onto underserved and inadequate reservations. We are a nation that passed thousands of Jim Crow laws between 1849 and 1950, banning Black people from “white-only” schools, hospitals, housing, and employment. We are a nation of sundown towns—the jurisdictions that passed laws from 1890 to 1968 that criminalized Black people and other marginalized communities. We are a nation that rounded up people of Japanese descent during World War II and placed them in internment camps.

As ever, history continues to repeat itself, sending the same message to marginalized groups: These are not your streets, and you don’t have the right to be here.

Grants Pass is a small town in southwestern Oregon, and one of hundreds of municipalities throughout the state that banned Black people from living in, or even passing through, the community. From the mid-1800s up until the 1970s, Grants Pass hung signs on roads and bridges directing Black people out of town. Grants Pass was also home to members of the Ku Klux Klan, who marched proudly and publicly each year in downtown “white pride” parades. The signs advertising the town’s ban on Black people have all been removed, but the town’s recent passage of anti-homelessness ordinances point to its continued strategy of disproportionately banning Black people and people of color from inside the township’s limits.

Today, Black folks make up only 1.92 percent of the entire population of Oregon, but they are disproportionately represented as 6 percent of the unhoused population. Black people, and other people of color who have been subject to housing discrimination, are more likely to face housing insecurity nationwide. Nationally, nearly 19 percent of Black households, 17 percent of American Indian or Alaska Native households, 14 percent of Latino households, and 9 percent of Asian households are extremely low-income renters, compared to 6 percent of white non-Latino households.

While the unhoused crisis has worsened in most of our cities since the 1980s, the suburbs that were created and zoned specifically to exclude the housing insecure and homeless are now seeing people sleeping in public spaces. The suburban landscape now includes more people sleeping on the cold, hard streets and in parks. This is the daily, visible reminder that our nation’s social safety net has been shredded by decades of federal, state, and local divestment.

Aside from being the cruelest response to homelessness, and a surefire way of exacerbating the crisis, criminalizing homelessness is a violation of several constitutionally protected civil rights that all US citizens—including those without homes—have. These include their right to due process, as well as their right to be free from cruel and unusual punishment. The criminalization of homelessness strips unhoused people of their right to property when the police take their tents, blankets, vital documents, medications, and all else they own—items that far too often end up in a landfill, rather than being returned to their owner.

Homelessness bans are snowballing throughout the country at a breakneck pace. The Cicero Institute offers homelessness ban templates to legislators and has spearheaded homelessness bans in 12 states. Florida Governor Ron DeSantis recently passed a bill that bans all unhoused people from sleeping outside in the state of Florida. If reelected in November, Donald Trump has promised to pass a homelessness ban nationwide.

Legal aid attorneys throughout the country have used their limited resources to seek justice for the victims of these civil rights abuses. Most notably, attorneys with the National Homelessness Law Center, Idaho Legal Aid Services, and pro bono partners were victorious in Martin v. Boise, a 2018 federal court case in the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. The court ruled that punishing people for life-sustaining behaviors like sleeping or sheltering oneself outdoors when there are no indoor places to do those things is unconstitutional. The legal protections won in that case are unfortunately often unenforced. Nonetheless, attorneys could use the decision to seek justice, and to build a movement dedicated to the realization of housing as a human right. This protection from harm, albeit limited, is at risk of being overturned when the Supreme Court announces its decision in the Grants Pass case.

Data proves just how ineffective punitive measures are because they also perpetuate homelessness by erecting more barriers to escaping the system of poverty. Incarceration disqualifies unhoused people from the support they need, including public housing benefits. A criminal record and credit scores wrecked by civil debt mean fewer employers or landlords are willing to give them an opportunity. A criminal record also severely limits access to healthcare, employment, and education. Once fees and fines accumulate, unhoused people are taken to jail, where they languish indefinitely without access to life-sustaining services. This can cause or exacerbate mental health challenges or substance use disorders. As a result of these practices, a staggering 15 percent of all people formerly incarcerated in the United States are unhoused. Counties throughout the country that are resistant to releasing a person from jail to the street choose instead to warehouse people for the crime of not having a home. Incarceration does not solve the unhoused crisis; it destroys people that are unhoused. People facing the heaviest fees and fines and the longest incarceration are disproportionately people of color.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Why are legislatures and cities choosing to attack their unhoused residents when they could attack the unhoused crisis instead? In 2023, the Housing and Urban Development Point-in-Time count revealed that 21 percent of individuals experiencing homelessness reported having a serious mental illness, and 16 percent reported having a substance use disorder. Legislation like Representative Cori Bush’s Unhoused Bill of Rights and the People’s Response Act are aimed at ending the unhoused crisis and investing in non-carceral responses to mental health crises.

The federal government knows what it would truly look like to solve homelessness because we’ve done it before—most notably after the Great Depression. In response to the economic crisis of the 1930s, the federal government invested in housing programs to end homelessness. From the 1930s to the 1970s, the federal government played a critical role in improving housing security for millions of households. By the 1980s, a precipitous federal disinvestment in affordable housing protections for working individuals and families led to a proliferation of homelessness. From the 1980s through today, the federal government has continued its path of housing program disinvestment, with one notable exception.

In 2020 and 2021, as a response to our Covid-19 crisis, our legislatures once more tested the noble solution to a public health threat posed by homelessness during a pandemic. Congress took bold action to support low-income renters: the Child-Tax Credit, Emergency Rental Assistance, Emergency Housing Vouchers, and a nationwide moratorium on evictions led to a significant decrease in homelessness, despite the pandemic’s negative impact on the economy. The CARES Act and American Rescue Plan Act brought the US poverty rate to a new record low of 7.8 percent in 2021, its lowest level since 1967. These gains might have lasted, with ongoing investment from the government. Instead, Congress allowed these resources and protections to expire, while renters faced a brutal housing market with skyrocketing rents and high inflation. This led to a resurgence in homelessness nationwide over the past two years.

The Supreme Court’s decision on the constitutionality of homelessness bans will tell us who we are as a nation. No matter the outcome of this case, Congress must choose the proven method of investing in housing, in communities, in people, and end the unhoused crisis for good. Regardless of the court’s decision, we must declare as a nation that our people are not disposable. We have a right to be on these streets. Whose streets? Our streets!