The Supreme Court v. My Mother

After my mother escaped the Holocaust, she broke the law to save her family. Her immigration story is more pertinent today than ever before.

Regina and Ben Treitler.

(Leo Treitler)In 1952, my mother, her brother, and her nephew stood before the US Supreme Court, accused of violating the 1945 War Brides Act. They had already been found guilty in the trial court, and that verdict had been upheld in the court of appeals. Now they faced their final confrontation. If their conviction was upheld at the Supreme Court, they would be fined and sentenced to prison.

The War Brides Act was enacted at the end of WWII as a way to permit the foreign spouses and children of US Armed Forces personnel to immigrate to the United States outside of the normal processes and restrictions imposed by immigration quotas at the time. More than 100,000 people entered the country this way, before the act expired in 1948.

My mother, Regina Treitler, had in fact violated the War Brides Act, but she justified her actions as the only way she could reunite her family after the Holocaust. My parents had fled Germany in 1938, right before Kristallnacht. They had saved themselves, but my mother had been tormented by the fact that her two brothers and her sister-in-law had not escaped. They were trapped in Europe for the duration of the Holocaust, their fates unknown. Other family members, such as my mother’s dear sister, had been killed by the Germans.

Immigration quotas the US government set, which at the time affected displaced European Jews, prevented my mother’s surviving family from immigrating easily—but the War Brides Act was a loophole: Foreigners who met and married American service members abroad were given swift and seamless entry and citizenship. So all they needed to do was get married. My mother, the savvy and indignant woman that she was, recruited two female veterans—a WAVE (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service) and a WAAC (Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps)—to marry her brothers in Paris, and persuaded her own nephew, my cousin Marcel, a US veteran, to marry his uncle’s wife (who claimed a past divorce) so that these three spouses could join her in Chicago.

Why tell this story now? The events happened almost 75 years ago, after all. Yet the issues that arose from the legal dilemma my family endured have recently come to my mind in light of our country’s current events: fears about a surge in antisemitism, questions regarding the prejudices of Supreme Court justices, and, most importantly, a new antagonism toward immigrants. As I read the front-page news, I find myself reflecting on this personal history, which thrust my mother, uncles, and cousin into the legal spotlight where, in the law texts, they forever remain. It is a cliché—but well-earned as clichés often are—that “those who forget the past are doomed to repeat it.” I hope that the history of my family drama serves as a significant cautionary tale for those now doing all they can to bring their families to America.

The question I keep asking myself is: Was my mother justified? Most of those years she spent in Chicago while her family was back in Europe, she had feared that her brothers had died; so you can imagine her relief when she had word they had somehow survived, hiding somewhere in Vichy France. She was ecstatic and eager to reunite her family by bringing them over to America and would do anything to make it happen.

The three arranged marriages took place in Paris, and had escaped scrutiny at the time, until a relative, a cousin on my father’s side who knew the truth, blackmailed my mother and threatened to report her to US Immigration if she did not invest in his fur business. When she refused, the cousin reported her; his wife wrote the betrayal letter, and my mother, her brothers, and her nephew were indicted. I learned of this fact only after reading it in a newspaper I picked up on my college campus.

To attend their argument before the US Supreme Court, my family, free on bail, traveled by train from Chicago to Washington, DC. The Chicago weather was uncharacteristically mild, not the usual blustery frigid conditions, only a chilly 34 degrees, but the dampness of the December day caused fog to press against the windows of the Liberty Limited and cloud over the skyline. Despite the terms under which she was traveling, my mother was excited to board this gleaming train, to hear the start whistle, to feel the wheels’ thrust as it pulled out of the station. It could almost feel like a holiday. And my mother, steadfast in her conviction that her family had the right to escape the postwar chaos, hoped a great legal triumph might lay before her.

Outside the train’s window, landscapes were obscured. This non-view matched the outcome of the appeal, which at this time, was still in limbo. The stakes were high—if the conviction of violating the War Brides Act were upheld, my mother, her brother Munio, and her nephew Marcel would have to serve time, probably years, in federal prison.

On this trip, the family were reduced to this trio—her second brother, Leopold’s case had been dismissed, as it appeared his marriage had possibly progressed from artificial to genuine, and the female veterans my mother paid off were not put on trial.

Knowing they would travel for 16 hours, my mother packed several meals and carried them in shopping bags. As ever, she had assumed there would be no kosher or even Jewish deli-style food beyond the radius of her own world in Chicago, so she had carefully wrapped bagels and lox with cream cheese, and a long, fragrant kosher salami. They all nibbled, more nervous than hungry. By the time they approached Washington, the bags were empty and their stomachs rumbled. But my mother pulled out a surprise pound cake, the price sticker still on the box. There was something about my mother: She always had to up the ante.

My family was in deep for their legal defense, a heavy roll of the financial dice. My mother and her other relatives had somehow managed to raise the ever-higher legal fees. She knew, better than anyone, it was now or never—acquittal or prison.

They had fought to get the hearing before the US Supreme Court, and, in a way, this in itself was a victory. Their case could have been denied and they would have been stymied ever more, with the guilty verdicts finalized.

But my mother, always able to squeeze out a little extra, would stop at nothing to keep her family in the United States. She paid their way through the trial and first appeal with money she had raised from her husband’s business and extended family members, and when those were over, she hired the best lawyers she could find to win her chance before the Supreme Court. My mother was an unusually forceful person, often to a near-comic fault. She approached her son-in-law who was a lawyer and demanded that he represent the family. When he refused, she threatened to jump out the window of his office. He obliged her by opening the window and providing a chair for her to stand upon to make her exit. She did leave, furious—but through the door.

Of course, she had been bluffing, and now she sat in the two-way train seat, jouncing along the rattling rail to the nation’s capital, headed, she hoped, for the ultimate victory. Aboard the train, the relatives had no view other than of each other.

My mother arrived in DC in her heaviest winter coat, the black Persian lamb with a silver fox stole, and even so, she felt nipped by the cold, her nose pink, and the wind drawing tears to her eyes.

Their case was scheduled to last for two days—December 8, and 9, 1952. Marcel had reserved two rooms at a hotel most convenient to the courthouse. The novelty of staying in the Hotel Washington, with its crisped bed linens, temporarily lifted everyone’s spirits.

“I know we will win,” Marcel said, as he carried their bags down the hotel hall. “It’s an all-Democrat court, and the justices were first appointed by President Roosevelt.”

But the justice they all looked forward to seeing most was Felix Frankfurter—often dubbed the “hot dog liberal” on the court. If anyone would clear them, it would be Frankfurter, they assumed; there was so much in his background that would lead him to take their side and vote to acquit. For starters, Frankfurter was not only a Jewish immigrant but he was also descended from a long line of rabbis.

My mother shared so many of his beliefs. “He’s going to understand us,” she predicted. (Though under her breath she muttered: “But he married a shiksa!”)

In 1919, Frankfurter married Marion Denman, a Smith College graduate and the daughter of a Congregational minister. They wed after a long and difficult courtship, and against the wishes of his mother, who was disturbed by the prospect of her son marrying outside the Jewish faith. Frankfurter was a non-practicing Jew and regarded religion as “an accident of birth.”

While judges are meant to be impartial, his background did suggest he might be most sympathetic to my family’s case. J. Edgar Hoover referred to him as “the most dangerous man in the United States” and a “disseminator of Bolshevik propaganda.” That seemed promising, from my mother’s point of view. But there were nine justices.

My relatives couldn’t sleep the night before their court date; too much was at stake. In the morning, they taxied to First Street Northeast, in Cleveland Park, to the impressive area of public buildings, where the Supreme Court Building loomed beautiful and dominant: the white marble edifice with its long rows of steps to ascend its portals. They paused on the steps and Marcel read aloud the engraved inscription: “Equal Justice Under Law.” We can imagine what this meant, almost promised, to the immigrant defendants.

Midway up the long flights of wide steps, my mother stopped to catch her breath. Inside, she was struck silent by the majesty of the courtroom, the long bench where the nine justices sat. She could hardly believe she had arrived here.

My family members almost tiptoed into the sacred Great Hall and then the actual courtroom, my cousin told me. The attorneys arguing cases before the court occupied the tables in front of the bench. When it was their turn to argue, they addressed the bench from the lectern in the center. A bronze railing divided the public section from that reserved for the Supreme Court bar.

The press was seated in the red benches along the left side of the courtroom. The red benches on the right were reserved for guests of the justices. The black chairs in front of those benches were for the officers of the court and visiting dignitaries.

My family’s case was publicized and notorious enough: Reporters filled the press section. This too raised my mother’s hopes. Injustice seemed more likely to occur in a vacuum. There was a podium for counsel to address the bench, and yes, there they were—the Supreme Court Justices. This was the Earl Warren Court: Along with Earl Warren, it was Hugo L. Black, Stanley Reed, Felix Frankfurter, William O. Douglas, Robert H. Jackson, Harold Burton, Tom C. Clark and Sherman Minton.

“Judge Frankfurter will help us,” my mother whispered to her brother and nephew. “He’s a mensch.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →While my family did not, in the end, win their case, Jackson wrote an eloquent dissent, with Frankfurter and Black joining in:

Whenever a court has a case where behavior that obviously is sordid can be proved to be criminal only with great difficulty, the effort to bridge the gap is apt to produce bad law. We are concerned about the effect of this decision in three respects.

1. We are not convinced that any crime has been proved, even on the assumption that all evidence in the record was admissible. These marriages were formally contracted in France, and there is no contention that they were forbidden or illegal there for any reason. It is admitted that some judicial procedure is necessary if the parties wish to be relieved of their obligations. Whether, by reason of the reservations with which the parties entered into the marriages, they could be annulled may be a nice question of French law, in view of the fact that no one of them deceived the other. We should expect it to be an even nicer question whether a third party, such as the state in a criminal process, could simply ignore the ceremony and its consequences, as the Government does here. We start with marriages that either are valid or at least have not been proved to be invalid in their inception. The Court brushes this question aside as immaterial, but we think it goes to the very existence of an offense. If the parties are validly married, even though the marriage is a sordid one, we should suppose that would end the case…

The effect of any reservations of the parties in contracting the marriages would seem to be governed by the law of France. It does not seem justifiable to assume what we all know is not true—that French law and our law are the same. Such a view ignores some of the most elementary facts of legal history—the French reception of Roman law, the consequences of the Revolution, and the Napoleonic codifications. If the Government contends that these marriages were ineffectual from the beginning, it would seem to require proof of particular rules of the French law of domestic relations.

2. “The federal courts have held that one spouse cannot testify against the other unless the defendant spouse waives the privilege. . . .” Griffin v. United States, 336 U. S. 704, 336 U. S. 714, and cases cited. The Court condones a departure from this rule here because, it says, the relationship was not genuine. We need not decide what effect it would have on the privilege if independent testimony established that the matrimonial relationship was only nominal. Even then, we would think the formal relationship would be respected unless the trial court, on the question of privilege, wanted to try a collateral issue…

3. We agree with the Court that the crime, if any, was complete when the alien parties obtained entry into the United States on December 5. We think this was the necessary result of the holding in Krulewitch v. United States, 336 U. S. 440. This requires rejection of the Government’s contention that every conspiracy includes an implied secondary conspiracy to conceal the facts. This revival of the long discredited doctrine of constructive conspiracy would postpone operation of the statute of limitations indefinitely and make all manner of subsequent acts and statements by each conspirator admissible in evidence against all. But, while the Court accepts the view or Krulewitch, we think its ruling on subsequent acts and declarations largely nullifies the effect of that decision, and exemplifies the dangers pointed out therein…

Despite these eloquent arguments to acquit, my family members were convicted, each sentenced to two years in prison and fined $10,000. When my mother received the decision, she is said to have slammed her fist onto the table and cried out “Antisemitism!” She had lost 6-to-3.

While many people today are still shouting about antisemitism, in the intervening years, public opinion has shifted in many ways. Quotas on Jewish immigrants do not exist, and the rules on the immigration of US veterans’ families have similarly relaxed. Nevertheless, as I read or watch the news, I feel a reflexive shiver. Nazi sympathizers are entertained by our present government, while the Israel-Gaza conflict has inflamed old hatreds. And while Jews are not today’s most disdained immigrants, Trump’s “America First” policies, the divisive Supreme Court, and ICE seizures targeting South and Central Americans, Africans, and Palestinians are painfully reminiscent of the isolationist era that forced my mother to commit a crime. While in our position we might reject our country, the American Dream still looms so large for some.

If you google “Regina Treitler” and “Marcel Lutwak,” the War Brides Act comes right up. My family became synonymous with the law they broke. And now I, the age my mother was when she died, feel that I am witnessing a painfully familiar rerun of history.

More from The Nation

ICE’s Terror Campaign Is Part of a Long American Tradition ICE’s Terror Campaign Is Part of a Long American Tradition

As a Black man, I know firsthand how often state violence is used to perpetuate white supremacy in this country.

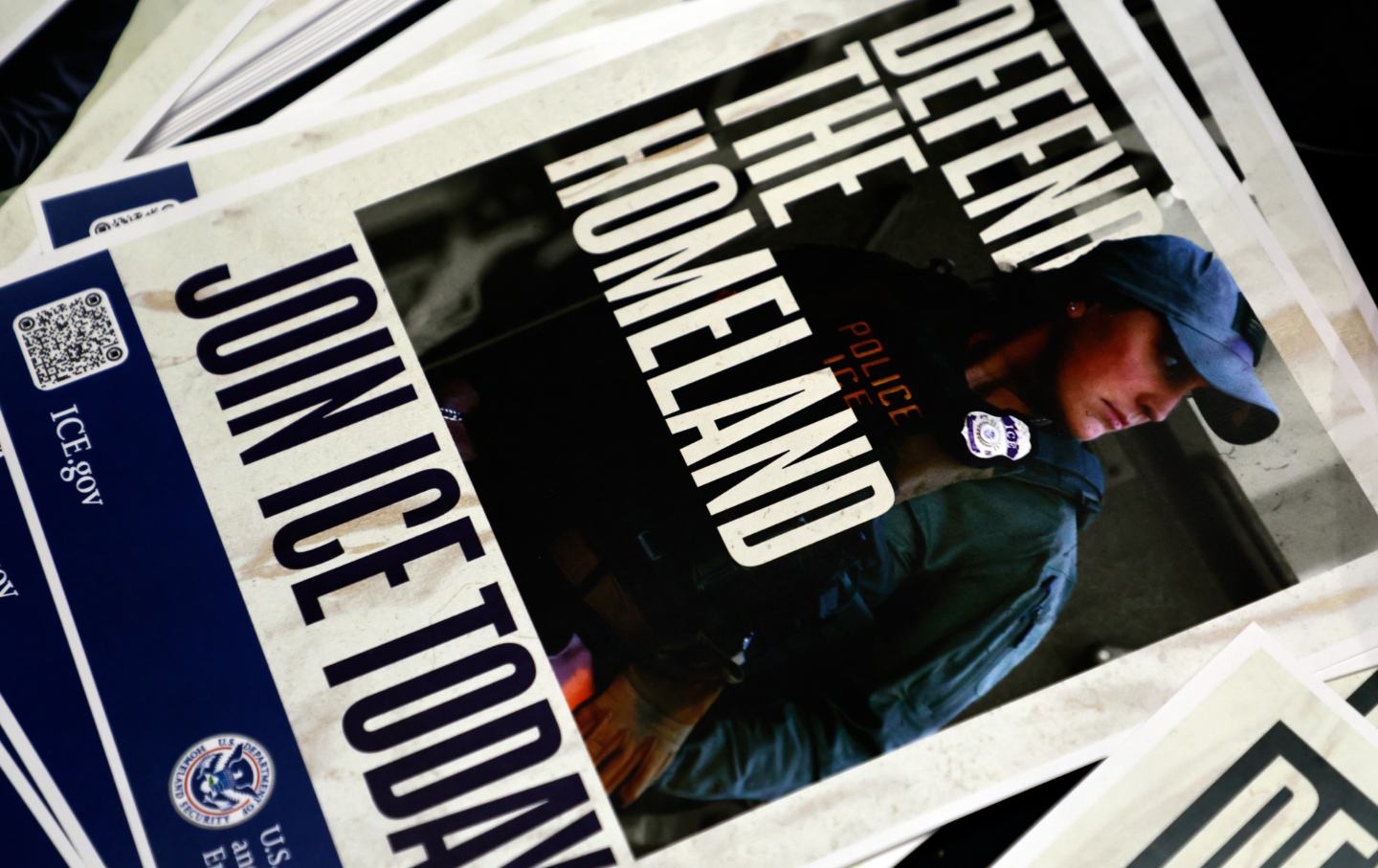

Whom Is ICE Actually Recruiting? Whom Is ICE Actually Recruiting?

ICE has lowered standards to facilitate a massive hiring spree. Many of the new recruits are plainly unqualified. Are some also white supremacists or domestic terrorists?

A Call Is Rising for Nations to Boycott the Trump World Cup A Call Is Rising for Nations to Boycott the Trump World Cup

As marauding state agents fill US streets, a leading German soccer official says countries should consider what was once unthinkable: skipping the 2026 World Cup.

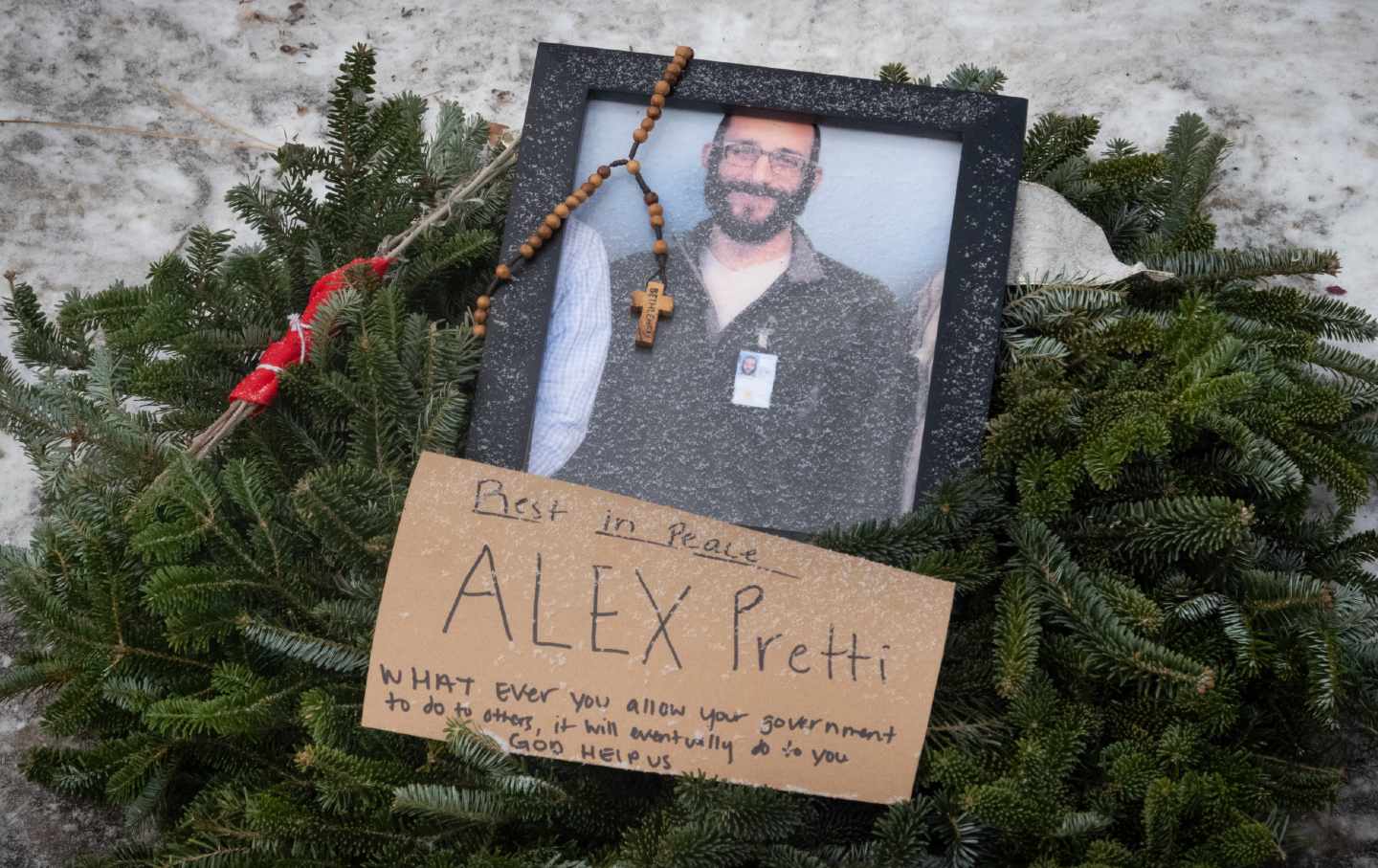

Alex Pretti Was a Good Man at a Time of Great Evil Alex Pretti Was a Good Man at a Time of Great Evil

The 37-year-old ICU nurse was killed helping another ICE victim. We must honor his sacrifice.

Minneapolis Is an “Insurrection” of Trump’s Own Making Minneapolis Is an “Insurrection” of Trump’s Own Making

The city has become ground zero for the Trump administration’s war on immigrants and the growing resistance to it.

Why I Didn’t Report My Rape Why I Didn’t Report My Rape

In 2021, six men sexually assaulted me in a Las Vegas hotel room. Something more than abolitionism prevented me from reporting the crime.