When There’s No One to Attend to the Dead

How one small change to Texas’s Code of Criminal Procedure created a cascade of problems for the state’s capacity to investigate death.

Chief Medical Examiner of Webb County, Dr. Corinne Stern’s autopsy assistant moves the body of an unidentified migrant to the autopsy room in Laredo, Tex., on October 12, 2022.

(Allison Dinner / AFP / Getty Images)On a Tuesday afternoon in December 2021, a police officer in Hidalgo County, Tex., found the body of 47-year-old Yvonne Salas on the kitchen floor of a mobile home. She had bloodshot eyes, blood leaking from her nose and mouth, and bruises on her face with dark marks that authorities suspected had been made by the ring worn by her boyfriend, Adan Roberto Ruiz, who had called 911 while drunk. Salas’s body was transported to the Nueces County Medical Examiner—the nearest available, at 140 miles away in Corpus Christi—and by Saturday, police had charged Ruiz with murder.

But in Salas’s autopsy report, there’s something odd. Though Sandra Lyden, then the deputy medical examiner for Nueces County, examined her body two days after her death, the report was written and signed by another doctor eight months later, using information from the case file. This is because, shortly after Salas’s autopsy, Lyden was arrested: She had no Texas medical license and lied about her history of criminal charges and prescription drug abuse on her application to obtain one. Though Lyden’s malpractice sounds extreme, it’s part of a long history of wrongdoing and poor oversight in Texas’s death-investigation system.

The systems that states use to respond to death vary across the United States, but Texas’s is especially unusual. Just 14 of Texas’s 254 counties have a medical examiner. In most of the state, elected officials called justices of the peace, who have no medical training, determine cause of death and sign death certificates. When justices choose to send bodies to other counties’ medical examiners for autopsies, the examiner keeps a substantial portion of the fee. There’s a high demand for limited services, and the profit motive can incentivize taking on more work than offices can handle.

Hidalgo County, where Salas died, was preparing to create its own medical examiner’s office, but then in 2019, the legislature changed the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure, weakening the state’s death-investigation system and indirectly giving rise to Salas’s insufficient death report. Now, some doctors and lawmakers are trying to change the law back.

More on Texas

Medical examiners play a crucial and often overlooked role in the US justice system. They identify remains after unexpected deaths like homicides, car crashes, and mass shootings, and provide evidence and expert testimony in cases of homicide and death in law enforcement custody.

The profession is relatively new: Most medical examiner offices in the US were founded between the 1950s and 1980s, allowing physicians to replace coroners—elected officials with limited or no medical training. Some states created medical-examiner systems that covered the entire state, but in many places, the transition happened only in cities.

Texas followed this urban model. Starting in 1965, the state required any county with more than 500,000 residents to create a medical examiner’s office, unless they had a medical school. Later, the state increased that threshold to 1 million, where it remained until 2019.

Texas is unique: In counties that have no medical examiner, the justice of the peace acts as the coroner. The justice of the peace position dates to 14th-century England and was brought to the US by colonists—but most states eliminated it during the 20th century as professional lawyers became common. Unlike coroners, who exclusively attend to deaths, justices of the peace have a variety of duties in addition to overseeing death investigations: They preside over small claims court, issue arrest warrants, and perform marriages, among other tasks.

Despite these many responsibilities, there are few requirements to become a justice of the peace. A candidate must be 18 years old, a high school graduate with no felony convictions, and have lived in the county for six months before being elected. They undergo 80 hours of training during their first year, and 20 hours of annual training thereafter, of which learning how to investigate deaths is just a small part.

As a result, justices of the peace are often ill-prepared to weigh in on deaths. Texas publications have covered problems of overlooked and misrepresented murders and suicides, unidentified migrant remains, and undercounted Covid deaths; academic studies have raised concerns about justices’ failure to recognize foul play in health-care-related settings like nursing homes and the skewed state death statistics that result from these oversights. “We hear horror stories where there are suicides that turn out to be homicides, and now they’re buried,” said Dr. Stephen Pustilnik, chief medical examiner of Fort Bend County, Texas. “The quality of death investigation is very variable when it comes to people who are elected death investigators.”

Justices of the peace get blamed for the failures in the death-investigation system, but their limited access to a professional medical examiner sets them up to fail. In cases of foul play or where there are questions surrounding a death, justices of the peace can send remains to another county for autopsy. But there’s a cost to the county, creating a disincentive to probing the cause of death any further.

Meanwhile, medical examiners aren’t obligated to accept out-of-county remains, and many don’t have the capacity to do so. But they also have an incentive to agree to the work: For out-of-county autopsies, the county and the physician split the revenue. In 2005, for instance, two medical examiners in Austin’s Travis County conducted 1,000 autopsies for 45 neighboring counties, accounting for over 80 percent of their office’s $2 million budget. Each examiner took home $300 per body. Dr. Pustilnik called them “masters of the 20-minute autopsy.”

The Rio Grande Valley, where Salas died, has over 1.3 million people. But it’s never had its own medical examiner’s office because no single county within it has ever reached the 1 million threshold. The valley spans four borderlands counties—Cameron, Hidalgo, Willacy, and Starr—and is divided into two metropolitan statistical areas: Hidalgo County’s McAllen-Edinburg-Mission metropolitan statistical area and Cameron County’s Brownsville-Harlingen-Raymondville statistical area.

The region is over 90 percent Latinx and has Texas’s highest rates of poverty; it also has multiple jails and detention centers and dozens of unidentified migrant deaths each year. The landscape shifts jarringly between environments that feel urban, suburban, small-town, and rural. The trailer park in Edinburg where Salas’s body was found, for instance, is on a block with four Mexican restaurants that faces a paper mill and, beyond it, lies a private prison; to the north, sorghum fields alternate with strip malls and housing developments, while just blocks to the south are the University of Texas–Rio Grande Valley, dense residential neighborhoods, and municipal buildings.

Though it didn’t have a medical examiner, for 13 years Hidalgo County did have something similar—it contracted a pathologist, Dr. Norma Jean Farley, to perform autopsies. But as it recognized that its population was nearing 1 million, Hidalgo began preparing to transition to a medical-examiner system. In 2017, the county built a new morgue and planned to hire Farley as chief medical examiner. Had Salas died 14 months sooner, or had things gone according to plan, her remains would have never left the county and ended up with Lyden.

Instead, in 2019, Republican state Representative Tan Parker sponsored a bill to increase the population threshold required for a county medical examiner’s office to 2 million residents. (Only four Texas counties have populations over 2 million.) Parker hoped to help his home county, Denton—the only other county in the state that was approaching 1 million residents and did not yet have its own medical examiner’s office—avoid the requirement to create one.

But Denton was in a special situation: In practice, it already had a medical examiner’s office. The county pays around $600,000 a year to be part of a district with the medical examiner’s office in neighboring Tarrant County. In contrast, according to Denton County Public Health’s public information officer, it would cost at least $11 million to start up their own facility and a minimum of $3 million annually to operate it.

While the change was intended for Denton, it ended up affecting Hidalgo County. No longer legally obligated to create a medical examiner’s office, the county called it off. In October 2020, Farley resigned. (Farley declined multiple interview requests for this article.)

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →County officials began sending remains to the Nueces County Medical Examiner, transporting bodies like Salas’s two hours each way for autopsies. According to invoices, Hidalgo paid the Nueces County Medical Examiner’s office $489,600 between January 2021 and March 2022 for its services; the county also had to cover the cost of transporting the remains.

Nueces County didn’t have the capacity for the additional autopsies, which totaled more than 100 in 15 months. Lyden told the Texas Rangers investigating the case that when she was hired, the chief medical examiner told her that he was in “dire” need of a deputy. (The Nueces County Medical Examiner’s Office did not respond to a request for comment for this article.)

The domino effect set in motion by Denton County—the 2019 change to the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure, Hidalgo’s cancellation of its medical examiner’s office, and the handling of Salas’s autopsy by an unlicensed pathologist—could have been avoided with a simple legislative fix: eliminating the population requirement for counties that were part of medical-examiner districts.

Recognizing this, Dr. Pustilnik reached out to Representative Tom Oliverson, a Republican and a medical doctor. Oliverson cosponsored HB 3895, which was introduced to the Texas state legislature in March 2023 and would have reverted the county population threshold to 1 million while adding the clause eliminating the population requirement for counties in district systems.

In the end, the bill died in committee. It was a late file, but also, said Oliverson, “it was a fairly nuanced issue, and I don’t think most people understood the implications.” Even he, as a doctor, wasn’t familiar with the issue until Pustilnik contacted him. But, Oliverson said, they’re likely to look at the topic again this session.

Though Pustilnik said transitioning the state to a full medical examiner system has always been the “pipe dream of medical examiners,” it’s more likely that the state will keep its justice-of-the-peace system for the foreseeable future. But in working with justices of the peace, he said he often thinks of a study conducted by Randy Hanzlick, a medical examiner in Georgia, who found that with sufficient training, elected coroners’ error rates could drop enough to approach those of medical examiners.

That’s a more feasible goal for Texas—and during the past two years, representatives from the agency that trains justices of the peace have collaborated with Texas State University and Houston’s Harris County Institute of Forensic Sciences to provide death-management training.

“That always stuck with me,” said Pustilnik. “Medical examiners are the best, but if you provide training, you can improve the coroners’ and JP’s outcomes.”

In August, the Nueces County Office of the Medical Examiner announced that it would stop performing out-of-county autopsies. Hidalgo County still has no medical examiner, but Dr. Farley returned to the county in 2022 as a contract pathologist.

More from The Nation

Deportation and the Silence That Follows Deportation and the Silence That Follows

When ICE abducted my father without cause, something strange filled his vacancy.

On Cora Weiss (1934-2025) and Peace On Cora Weiss (1934-2025) and Peace

Cora Weiss died in December at age 91. She never stopped campaigning to save the world from nuclear destruction.

The Media’s Coverage of the Venezuelan Coup Has Been Dreadful The Media’s Coverage of the Venezuelan Coup Has Been Dreadful

War may be the health of state, but it’s death to honest journalism.

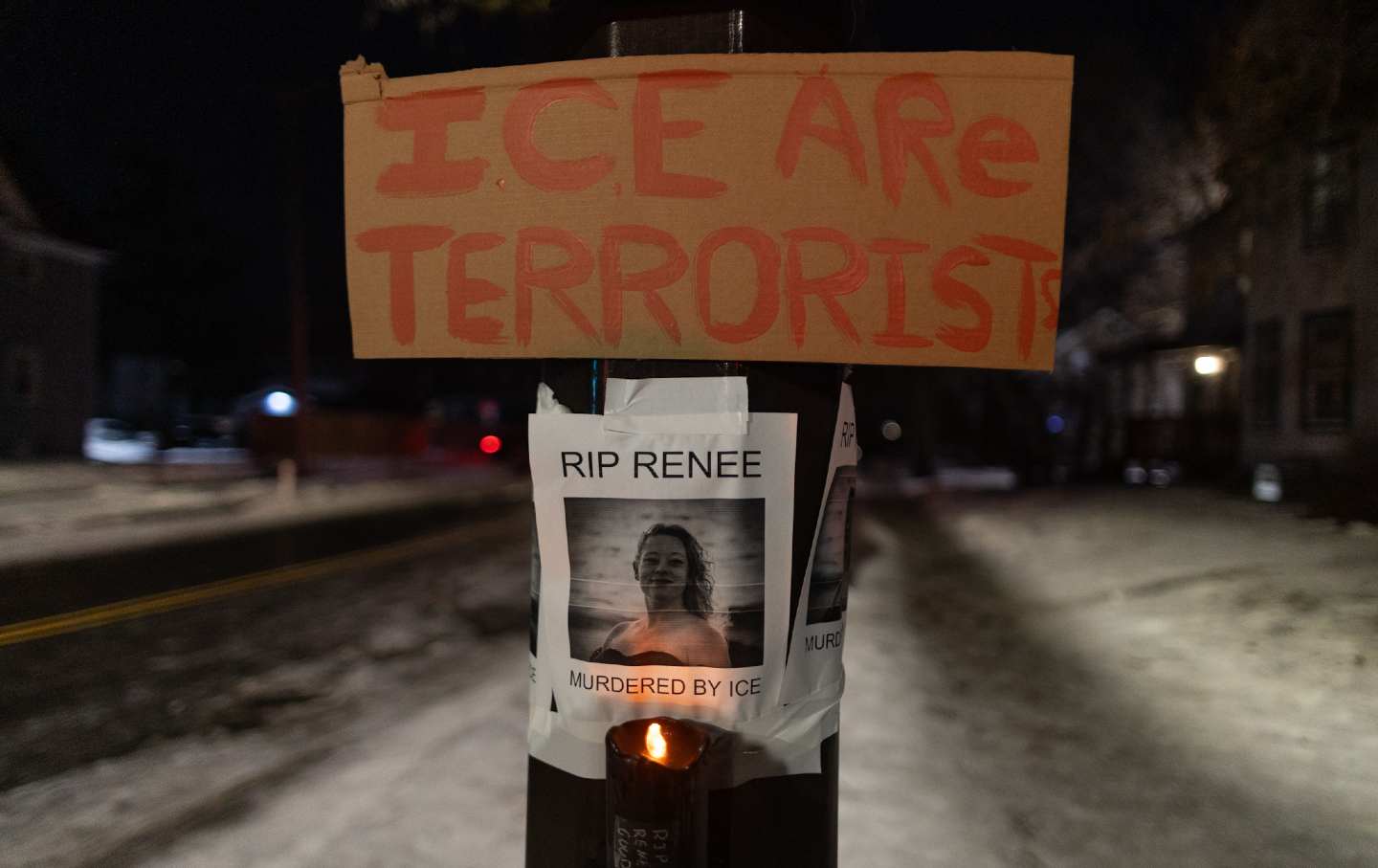

Dismantling the Meme Logic Behind Renee Good’s ICE Execution Dismantling the Meme Logic Behind Renee Good’s ICE Execution

The Trump administration is once more invoking upside-down alibis of state to conjure the bogus specter of imminent threat.

Minneapolis to ICE: Get the Fuck Out! Minneapolis to ICE: Get the Fuck Out!

An ICE agent shot dead Renee Nicole Good. Residents are ready to fight back.

Prosecute Renee Nicole Good’s Murderer Prosecute Renee Nicole Good’s Murderer

The ICE agent who killed Renee Nicole Good not only can be held accountable for murder—he must be.