These Would-Be Teachers Graduated Into the Pandemic. Will They Stick With Teaching?

We tracked down nearly 90 members of the University of Maryland College of Education’s 2020 class. Their experiences suggest that the field isn’t doing enough to help new educators.

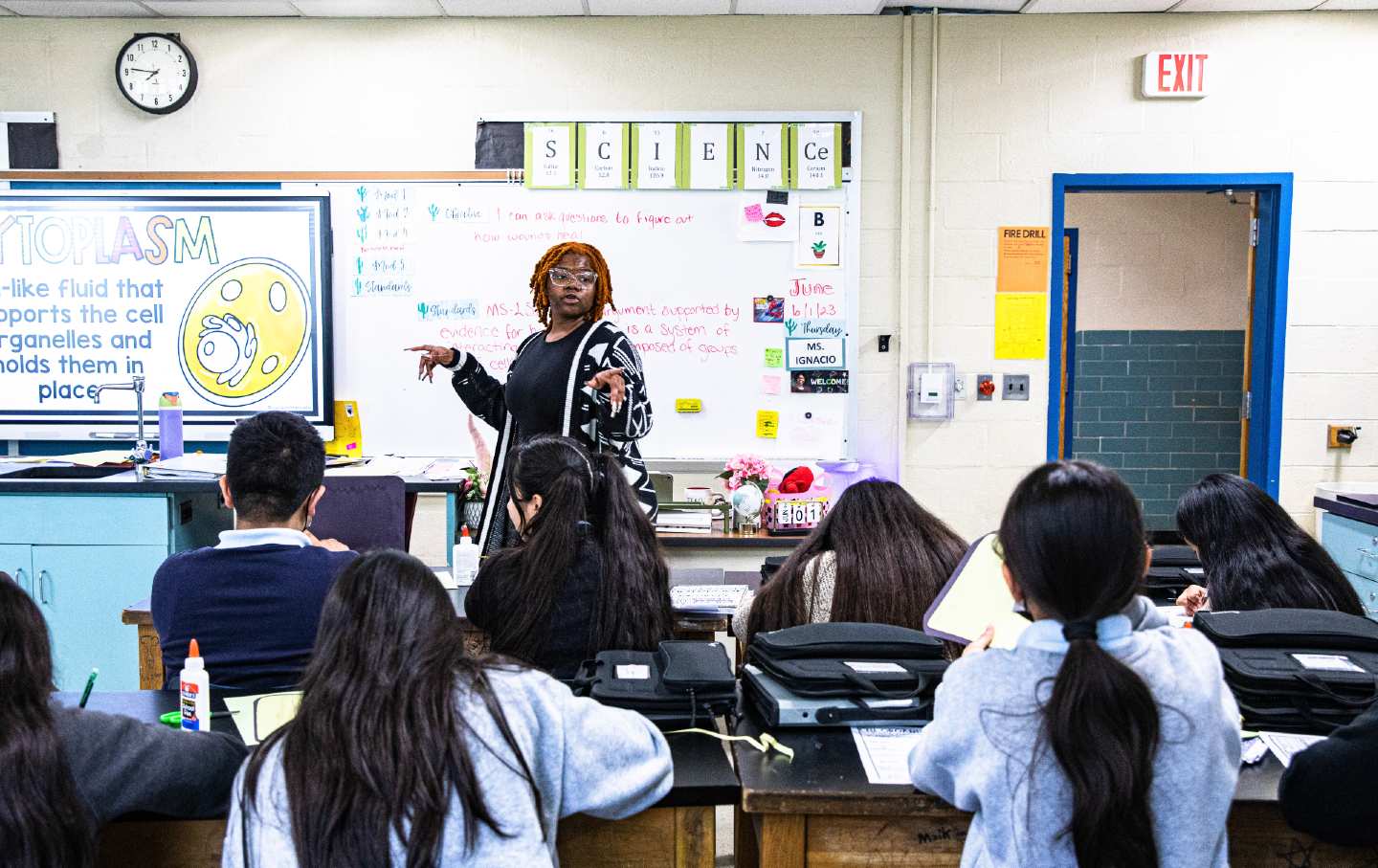

Sydonne Ignacio goes over some of the parts of a cell with her sixth grade science students at Buck Lodge Middle School in Adelphi, Md.

(Valerie Plesch for The Hechinger Report)At the end of her first day as a full-time teacher, Caitlin Mercado logged out of Zoom and turned off her computer in her parents’ basement.

Then she cried.

Mercado had wanted to be a teacher ever since she’d spent time in high school working with preschool kids.

But the remote lessons she was teaching to second graders at a Silver Spring, Md., elementary school didn’t resemble the in-person classes where she learned her craft in college as a student teacher. Preparing for each day required creating an elaborate set of slides that would encompass more than six straight hours of lessons she’d never taught before, with contingencies for any moment a child struggled with technology or school supplies.

“I’d stay up late, wake back up, keep going,” Mercado said, telling herself, “‘I’m just going to push through and do what I have to do for these kids.’”

Still, her second graders would sometimes fall asleep in the middle of the day, tired of staring at the screen or, she guessed, from having stayed up at night playing games or watching videos on their new, school-provided Chromebooks.

On social media, Mercado glimpsed videos of other teachers who were quitting their jobs, including educators with far more experience than she had. A deluge of similar clips ended up in her feed.

She found herself, at moments, wondering whether she had made the right career choice. “This is really not what I thought it would be,” she remembers thinking.

The number of people studying for careers in education has been declining for years. At the same time, schools have struggled to hold on to new teachers: Studies indicate that about 44 percent of teachers leave the profession within their first five years.

Then the pandemic came along, hammering teachers and the profession as a whole. Surveys from the National Education Association and the nonprofit research organization the RAND Corporation found teachers, both new and experienced, contemplating quitting in greater numbers than in the past. Research from Chalkbeat found that, in eight states, more teachers than usual made good on those feelings and left their jobs during the pandemic. Federal Bureau of Labor Statistics data show a higher rate of people working in education quitting as of February this year than in the same month in 2020. And results from a study released late last year found that teachers were 40 percent more likely to report anxiety during the pandemic than health and other workers.

“The first three years of teaching are really, really hard even in a perfect school system,” said Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers. So for teachers who entered the teaching profession at any point during the pandemic, “this has been a helluva ride.”

To learn more about the difficulties facing new teachers in the aftermath of the pandemic, and what’s needed to retain them, The Hechinger Report contacted a half-dozen schools of education to access lists of or data about graduates to see how many remain in the field. Most declined to share the information or said they didn’t keep those records, but Hechinger identified a list of 2020 graduates from the University of Maryland College of Education and attempted to track them all down. Of the 120 teachers who earned bachelor’s degrees in education that year, The Hechinger Report was able to verify that at least 77, or roughly two-thirds, are teaching now.

Hechinger spent the past year following four of those graduates: Mercado, 25; Miriam Marks, 26; Sydonne Ignacio, 26; and Tia Ouyang, 25. The reporting revealed how unprepared they felt at times, showed their feelings of anxiety and depression, and explored their thoughts about quitting as well as the moments of joy they experienced—and whether they see themselves teaching for the long term.

Yet, even with teachers, new and veteran, so rattled by pandemic teaching and concurrent culture wars, districts may not be adapting. The effort put into supporting and retaining newly hired teachers rarely matches the lengths districts go with hiring in the first place, experts say. The constant churn in the teaching workforce can be destructive for students—leading to bigger class sizes, fewer class offerings, and less-qualified, less-experienced candidates filling vacancies.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Yet teachers are considered the most important factor in students’ success at school.

“That new teacher is in front of our students. That person has the most power to change the trajectory,” said Sharif el-Mekki, the CEO of the nonprofit Center for Black Educator Development. These teachers require a lot of support: additional training, a sense of belonging, and the right mentoring.

Many don’t get even some of that.

“If we’re too busy to do that,” el-Mekki said, “we’re too busy with the wrong things.”

Some Sunday afternoons, fifth grade math and science teacher Miriam Marks scours Amazon looking for goodies—squishy animals, sticky toys, slime—to put in her classroom prize box at Weller Road Elementary in Silver Spring. All week long, kids who participate and complete their assignments might snag a popsicle stick from Marks. She tallies them up at the end of the week, and those who have shown the right amount of effort can rake through the box of trinkets.

This is all part of a new routine for Marks.

Because Covid hijacked her final months of college, she missed key experiences before starting a full-time job. After a few months of working closely with another teacher during her senior year, Marks was supposed to take over the class for the final weeks of the semester.

“We never got to that end point,” she said. “I went from teaching the occasional lesson or two a day to Covid to, ‘Here: You’re hired.’”

After the end of the term, and a virtual graduation ceremony, she moved into her own apartment, too afraid of harming her asthmatic father’s health if she moved home. It would mean spending a lot of time alone, with occasional visits with her sister and outdoor walks with a friend before the remote teaching of the 2020–21 school year would kick off.

Once it did, she found herself laboring to make math exciting via Zoom to a group of fifth graders at a high-poverty school, some of whom sometimes failed to log on at all.

Alone in her apartment, she couldn’t pop into the classroom next door for quick advice. While she did meet regularly with a supportive mentor teacher assigned to her by the school, Marks struggled to gauge if she was floundering or facing hurdles similar to fellow teachers’.

The experience stirred up anxiety and depression that she suspects she’d long had. She started to have suicidal thoughts.

“I had to start therapy,” Marks said. “If I’m not mentally healthy, how can I be a good teacher?”

In addition to regular visits with a counselor, once in-person teaching resumed Marks was able to build a connection with another, more experienced coworker who was also new to the school. His support, she said, along with near-daily kickboxing sessions, have been integral to her persistence.

On a Tuesday in April, in her Weller Road classroom, Marks launches into a lesson on the parts of a plant and photosynthesis, gliding through the classroom in black slip-on sneakers, her hair woven into a side braid that nearly reaches her waist. When students chatter or stop paying attention, Marks quickly steers them back on course.

“You just need to listen,” she tells Re’Niyah James, 11, who is looking down and scribbling. “If you’re too busy writing, you can’t listen.”

Then it’s time for students to label a diagram of a plant and explain how its parts work.

Dozens of clear plastic cups cover the top of bookshelves under the windows in her room. Each is stuffed with seeds nestled in damp paper towels. They are labeled—bush bean, peas, popcorn—along with students’ names.

Ivana Miranda, 10, hands in her assignment, then peers at the cups.

“Ms. Marks,” she exclaims, “the bean sprouted.”

Next it’s time for a math lesson on quadrilaterals. It’s where Marks wants to be especially sure the kids follow along, given how difficult she once found math to be.

In high school, she despised the subject. But one year, after being placed in a class for lower-performing students led by a teacher who wasn’t particularly engaged, Marks surprised herself by discovering that she had enough of a grasp on the material to assist her classmates.

That experience catalyzed her interest in teaching. Marks said she summons her recollections of distaste for school when she teaches.

“How can I prevent that from happening?” she said later. “I relate so much more to my kids who struggle than my A+ students. I understand, and can, on a more personal level, be more real with those kids.”

Since Covid, teaching has become more challenging, in part because the troubles students bring to school have grown more intense. Misbehavior in class is on the rise, according to surveys of teachers. Tens of thousands of school-age children lost parents or other family members to Covid. National test scores show that students have backslid in many subjects. Classroom teachers at all levels of experience are under enormous pressure to make up that ground.

Despite those difficulties, and the challenges many districts have faced in filling open teaching positions, there’s been little investment in hanging on to the teachers already on staff, said el-Mekki, a veteran principal and teacher himself.

“Speaking to school and district leaders around the country who recruit, recruit, recruit, when we ask about their retention plans,” el-Mekki said, “we get blank stares.”

He said that, too often, new teachers spend little or no time with their principals, lack effective mentors, or have no feeling of community at their jobs.

They may also need help with practical skills—organization, managing students’ behavior, and communicating with parents. “It’s one thing to have it from a theoretical perspective” in college, el-Mekki said. It’s another to suddenly contend with the grading and family interaction for say, more than 100 students.

While the teachers in the program at Maryland noted that they started spending time in classrooms as college sophomores, “most people don’t have a whole lot of student teaching,” Weingarten said.

The quality of those experiences vary widely, but when student teaching is done right, research shows, it can give a novice teacher the same kind of effectiveness as someone with far more experience.

Most new teachers, however, even those whose degrees required a lot of in-person teaching experience, which is usually unpaid, haven’t communicated with families while in training. That’s left to the teacher supervising them.

And despite federal laws ensuring that employers treat mental health conditions just as they do physical health concerns, many state and local government workers, including teachers, have health plans that limit treatment or have strict preauthorization policies. A bill passed by the US House last year was intended to bolster access to mental health care for educators and students, but it wasn’t taken up in the Senate.

Nothing, however, will keep all teachers, or graduates with teaching degrees, in the classroom.

Maryland graduate Tia Ouyang loved her early experiences with a program aimed at recruiting more science and math teachers by drawing in students majoring in those fields.

Ouyang was a sophomore chemistry major when she added education as a second degree to ensure that she would get a job after graduation. After working with middle school students, she felt that high school would be a better fit.

In the classroom, she enjoyed talking about science and answering students’ questions—even planning her lessons. But Ouyang felt that the high school students were reluctant to trust her, an Asian woman with an accent. Her science instinct kicked in as she recalled this, though, and she noted that she had no real evidence that this was the case.

When public schools switched to remote instruction, and there were no more of those engaging conversations about science with students, she lost motivation.

With online instruction, “All you are doing is talking,” Ouyang said.

At home, disconnected from her own schooling and the high school students, she ended up applying as her final semester ended to a program at the University of Delaware Lewes in chemical oceanography.

Ouyang, now enjoying her doctoral program, said she never let go of the idea of being a teacher. She wants to encourage young people to study chemistry and nurture future scientists and environmental leaders—but as a college professor.

“I feel happy about my life.”

Ouyang’s choice is especially painful for the profession: Losing science and math teachers to other work is a long-standing problem for districts across the country, making these some of the hardest roles to fill. And just 2 percent of the US teaching workforce is Asian.

Other Maryland College of Education grads The Hechinger Report tracked down left science and math teaching jobs too, in one case to work for an international science and medical equipment company. Another member of the class of 2020 works as a customer service specialist for a Miami-based financial services company. One chose to work at her family’s bakery. Yet another owns a dance studio. One calls herself a former educator who left teaching after two years in search of “a remote position to pursue a more healthy work-life balance.”

Sydonne Ignacio, like Ouyang, never intended to be a teacher. When she enrolled at the University of Maryland, she was an aerospace engineering major embracing her love of science and math. But by the end of sophomore year, she was limping along.

“I was completely miserable,” said Ignacio, who also worked two jobs for much of college.

Although her advisers tried to persuade her to stick it out, Ignacio said she wasn’t sure it was worth sacrificing her mental health for her major. She chose education instead, with many of her credits neatly aligning with a middle school math and science degree.

Ignacio said she chose middle school in part because it’s such a pivotal time in children’s lives. And because she loathes the refrain “I hate math.”

“I love math. I love science. I love learning,” said Ignacio, who eventually wants to return to school and complete her engineering degree. “I want to instill that passion in my students—so maybe math sucks a little bit less.”

Ignacio, who’d wanted to teach math after graduation, ended up with an offer to teach science at the school where she student taught, Buck Lodge Middle in Adelphi, Md. She considered working elsewhere but said she valued the familiarity, given how much the pandemic upended everything else in her life.

Nevertheless, remote teaching that in her district dragged on for essentially all 10 months of the school year drained her. Her classes included two sessions that were a mix of students with disabilities and lower-performing students, a group with more average skills, and an honors science course. Each class required a distinct set of lesson plans.

Even though she was familiar with Buck Lodge staff, Ignacio’s mentor taught math, not science, so she couldn’t go to her for lesson planning help. In addition, Buck Lodge is a Title I school, meaning many students are from low-income families. With that in mind, Ignacio tried to devise experiments that involved items almost any family would already have at home.

“I didn’t want them to have to go out and buy anything,” she said, but crafting those lessons took a lot of time-consuming research. And as a new teacher, she had no old lesson plans to fall back on or adapt from.

Most of the week, she was exhausted, and at times it was hard for her simply to get out of bed. “Sometimes I would teach from my bed,” Ignacio said. “I would have my camera off, just going through the motions.”

Ignacio also experienced the kind of heartbreak that often comes with teaching, pandemic or not. She powered through teaching the day her grandmother was admitted to the hospital; her grandmother died a few months later. (“I don’t want my students to ever see me in a moment of weakness.”) And when one of her former students discovered that his father had died by suicide, his attendance plunged, despite Ignacio and other teachers pressing him to come to school and checking on him as much as possible. He wound up being arrested along with his older brother on an armed robbery charge. The student rarely attended after that.

“Sometimes I would feel so helpless. I can’t follow him after school and make sure he’s doing the right thing,” she said. Other students have chaotic home lives, she said. One is homeless. “If I could buy them a house, I would.”

“That’s one of the downsides. You want to do everything for the kids, but you can’t.”

Ignacio herself still lives with family, unable to afford to move out.

Still, she finds room in her budget to stock her room with Takis, granola bars, and Cup Noodles, rewards for attending school all week.

In addition to traveling and practicing yoga, one of the ways she copes is blasting R&B, dancehall reggae, or as she described it, “really vulgar rap music” on the drive home.

Ignacio said she’s unsure teaching is what she will do forever. “The mental wear and tear is a little bit too much for me,” she said. “I don’t know if I can do this for 20 years.”

But for now, she’s tried to turn her difficult experiences into a positive: This fall, she’s set to be the Buck Lodge science department chair. And she still gets a thrill when her teaching results in a concept clicking in her students’ minds.

One lesson this spring for her sixth graders during a unit on states of matter—solids, liquids, and gases—dealt with condensation. At first, they didn’t understand.

When they finally did, they regaled Ignacio with their discoveries.

“When I come in from outside, my glasses get foggy,” one of them told her. “This is the water vapor in the air that is cooling into liquid.”

Exactly.

For Mercado, there have likewise been small moments as a teacher when she thought, “This is really not what I thought it would be.” But she said she now believes she’s found what she’s meant to do.

She too turned to therapy, in the fall of 2021, to help manage her stress. The therapist offered concrete ways to keep from getting overwhelmed. For instance, if five students swarm her desk, she asks them to take a seat and tells them she will come to their desks to answer questions instead. She started taking lunch breaks instead of working right through them. A diffuser pipes the scent of lavender into her room. Bright fabric that mimics the clouds and sky covers the fluorescent rectangles of light on her classroom ceiling.

During her second year of teaching, Mercado also recognized that she needed to take another dramatic step to survive: work at a different school with fewer low-income students. She requested a transfer and got her wish for the upcoming school year. Mercado said it is a prime reason she has stuck with teaching.

Historically, new teachers are more likely to get jobs in high-poverty schools than in low-poverty ones, which also tend to have more turnover.

At her old school, “the students need a lot of support. I didn’t feel like I had enough experience to do that,” she said.

Now, she is in her element in a second-grade classroom at Ritchie Park Elementary in Rockville, Md., but she also makes time for her boyfriend and dance—Mercado was on the college dance team—in addition to preparing her lessons each day.

For a recent assignment, her students—preschoolers when the pandemic hit—had to reflect on each year of their schooling so far. They take turns sharing their experiences about trying to learn online as kindergartners and getting to be together, sort of, as socially distant first graders.

Chris DiFrancesco, 8, stands up to share how things are going this school year.

“I feel like Covid is gone,” he says.

“Maybe put an emotion in there,” Mercado replies. “Do you feel hopeful?”

“I feel hopeful.” Mercado does too.