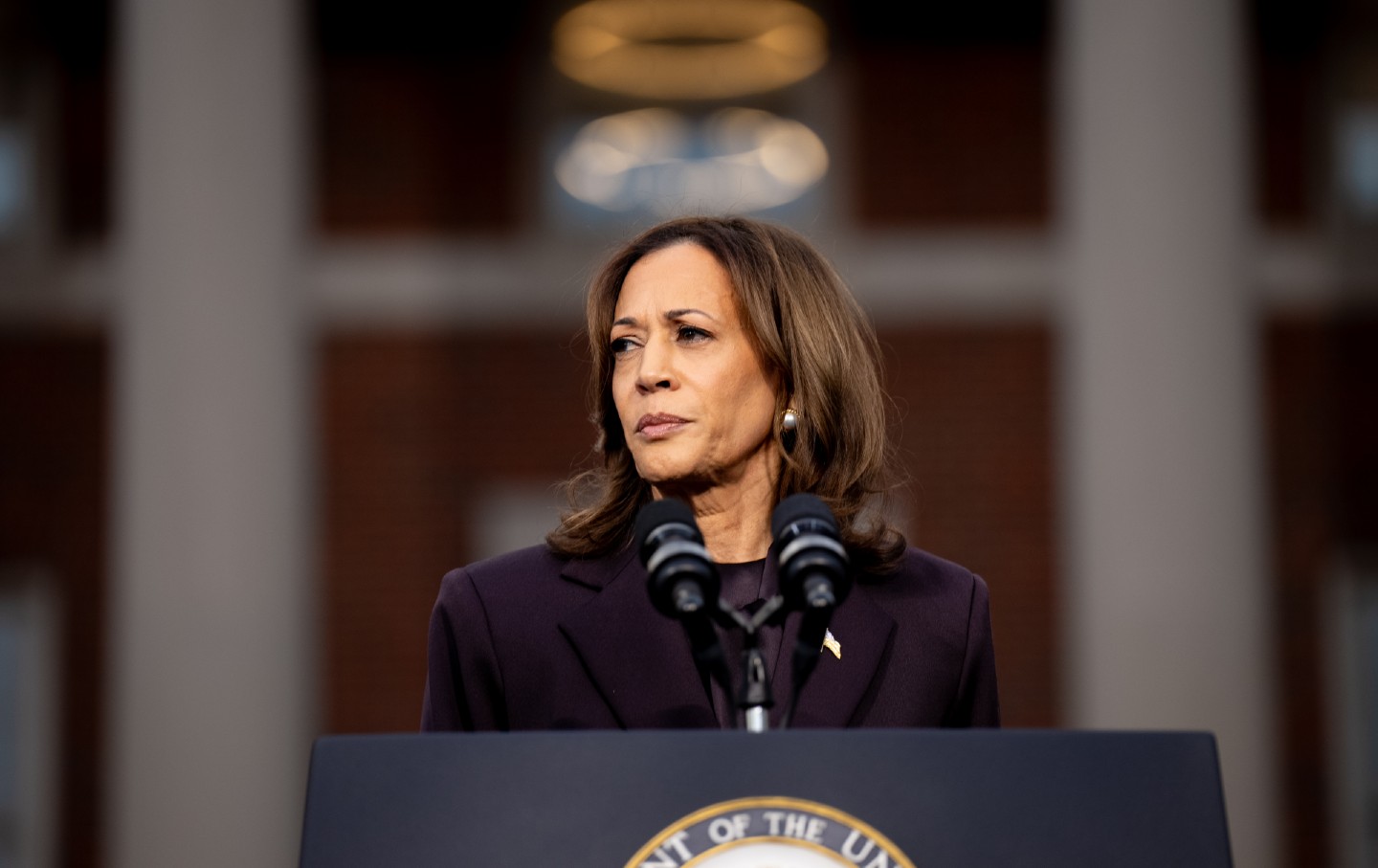

Kamala Harris Steps Up

The future of American democracy now rests on the vice president’s shoulders. That’s why it’s more important than ever to understand who she is.

Illustration by Victor Juhasz.

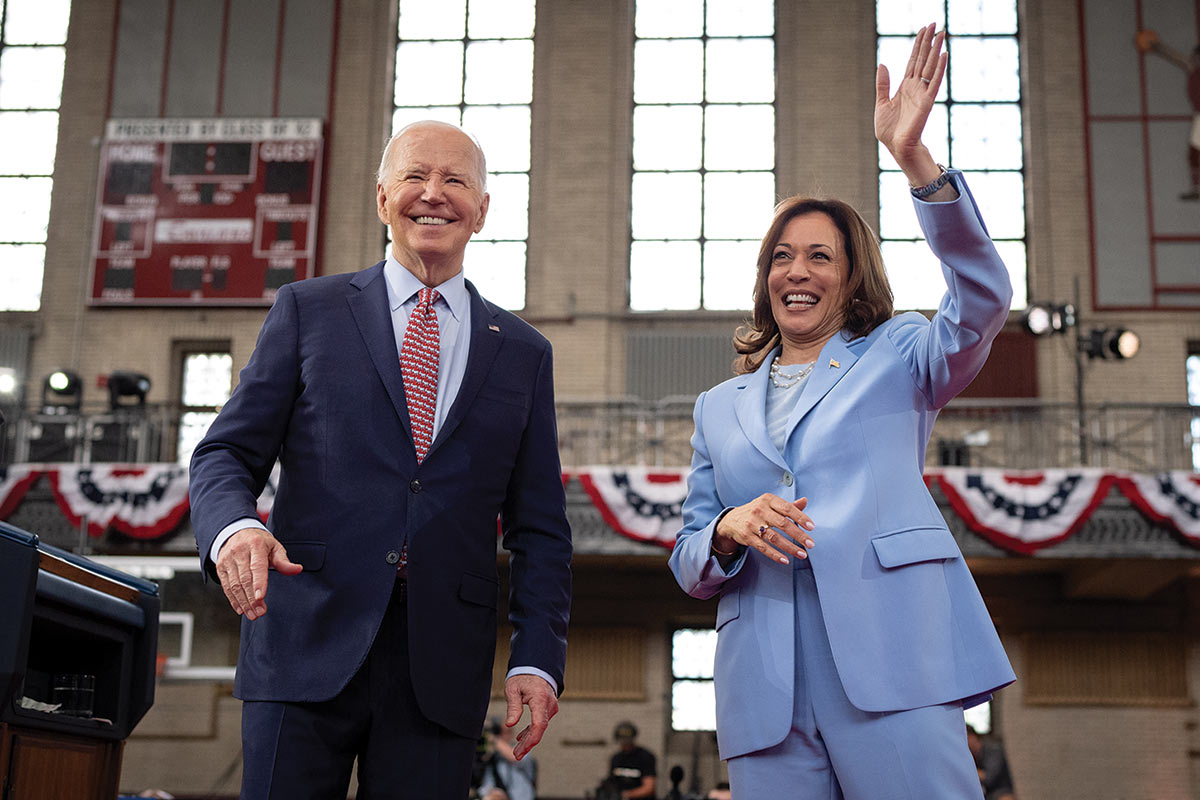

New York City—I sat down with Kamala Harris on a scorching June afternoon, one of a nearly week-long string of 90-degree-plus days. Staffers escorted me to a well-cooled hotel room that had been made over into an interview chamber. I sat at a spare table where a bed would normally be. It was draped in one of those forlorn table skirts and set with two empty glasses, and the window’s thick curtains were closed to the midday sun. It was a little bleak.

I heard the rapid staccato click of high heels. Harris walked in, greeted me warmly, and immediately yanked open the curtains. She was not afraid of the heat. She wanted sunshine in here.

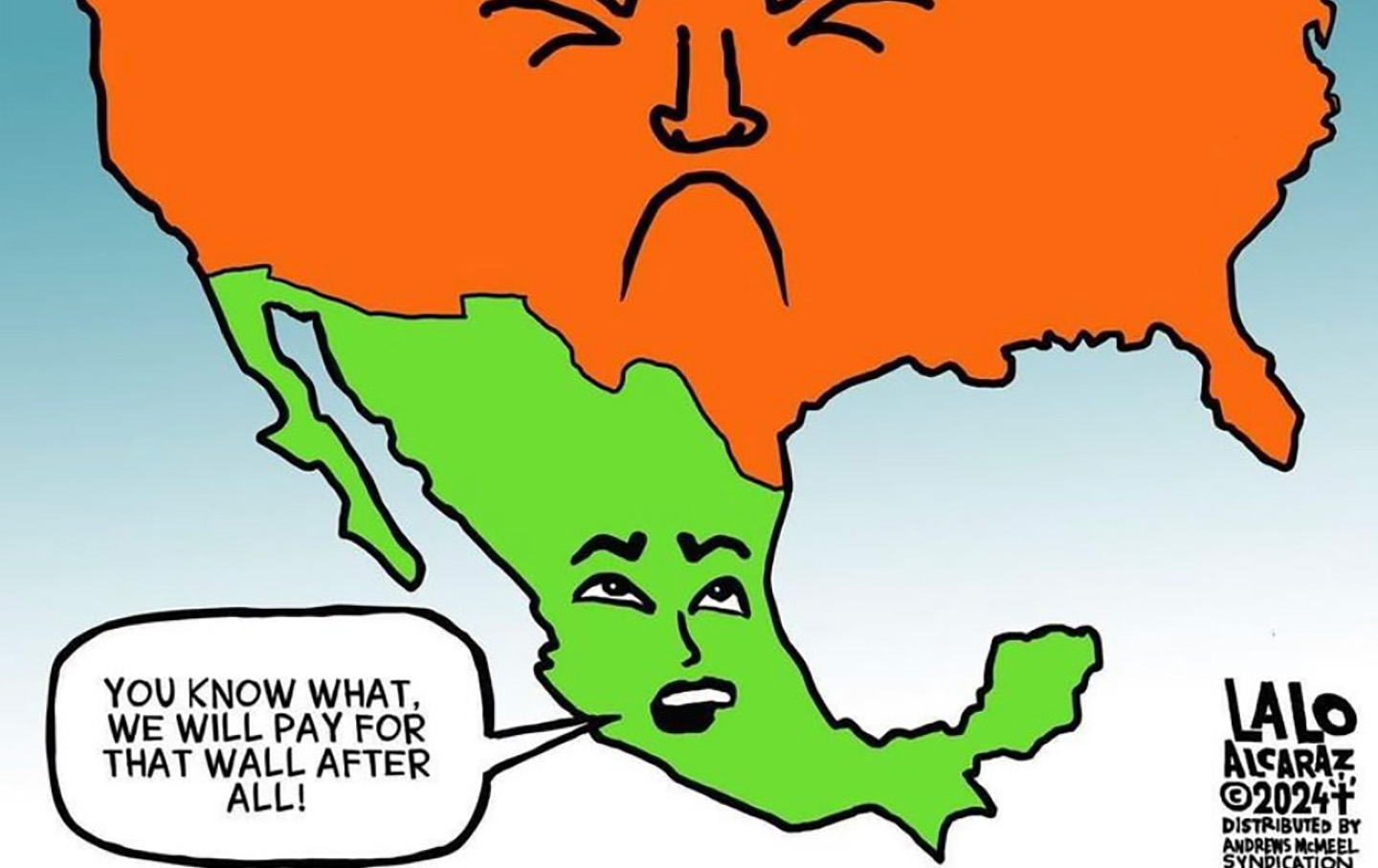

She is about to get much more sunshine—and heat—than she asked for. A few days after our conversation, President Joe Biden had the worst debate performance of his career and sent the Democratic Party into a crisis over his ability to win the 2024 election against Donald Trump. Pundits and more than a few Democratic leaders clamored for Biden to step aside, as polling showed his path to a second term drying up. On July 21, Biden announced that he was suspending his campaign for president and endorsed Harris as nominee soon after. Prominent Democrats quickly lined up behind her as her work wooing Biden’s delegates began.

Harris and I spoke when she was still trying to win a second term for Biden, dispatched to reach voters who were among the most critical to his reelection. In the days before I met with her, I was repeatedly told: Do not suggest that she’s “found her voice” in the two years since the ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, when the Supreme Court robbed American women of rights we’ve enjoyed for half a century—although she kicked off her Dobbs anniversary tour the day we spoke. Do not say that she’s “having a moment” on the 2024 campaign trail. Or ask if there’s any “daylight” between her and the president over Israel’s brutal retaliation against Hamas in the wake of the October 7 massacre. (On policy, there isn’t, though Harris has been more critical in public about the mercilessness of Israel’s response and the toll on Palestinian civilians than Biden has.) Do not ask whether anything “surprises” her after a long career as a district attorney, an attorney general, a senator, and now as the nation’s first Black, first Asian, and first woman vice president. This struck me as a defensive tic, a reaction to the feeling that she has repeatedly been underestimated. (That feeling simmers under the surface of our conversation as well.)

I was warned against going down these paths not just by her staff but by some of the friends who’ve known her for decades. They were not protecting her; they were protecting me—from her impatience with what she thinks are stupid questions she’s heard time and again.

So I struggled with how to phrase a question about whether Dobbs has given her a new mission. I think I maybe even used the dreaded word “moment.”

“I appreciate that perhaps for some who weren’t paying attention, this seems like a ‘moment,’” Harris allowed. “But there have been many moments in my career which have been about my commitment to these kinds of fights, whether they’re on the front pages of newspapers or not.”

The problem, though, is that Harris could use this redemption story. Her 2020 presidential primary bid went poorly. (Full disclosure: My daughter, Nora, was her Iowa political director in that race. I also worked with her sister, Maya Harris, at an Oakland nonprofit 25 years ago.) The first year or so of her vice presidency didn’t shine. The past two years have been different: Since Dobbs, she has been Biden’s top ambassador on issues of reproductive justice—yes, unlike Biden, she’ll say “abortion,” but she also frames the issue around broader themes of maternal health and family support. When we met, Harris had just come from a taping at MSNBC where she sat alongside Hadley Duvall, the brave Kentucky woman who spoke about being raped by her stepfather and becoming pregnant at 12 and railed against Republicans who would force girls to have their rapist’s baby.

Duvall had a miscarriage but remembers she took comfort in knowing she had “options”—options she wouldn’t have now in Kentucky or in many other states. “One of the things I’m utterly in awe of is the number of people who have decided, ‘I’m gonna tell my story, because I don’t want other people to go through this,’” Harris told me. “I said to Hadley, ‘I’ve seen, in moments of crisis, the universe has a way of revealing the heroes.’”

After Biden’s catastrophic debate performance and declining poll numbers, the Democratic Party needs a hero. Can Harris pull it off? Senior Democrats as well as some progressives who had been pushing Biden to stay in the race have lined up behind her, including former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, Senator Elizabeth Warren, Bill and Hillary Clinton, and Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. At press time, former President Barack Obama had not endorsed Harris, yet several of Harris’s strongest presumed rivals for the nomination, including California Governor Gavin Newsom and Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer, had. ActBlue reported raising nearly $50 million in small donations in the seven hours after Biden’s announcement. Now the way in which she navigates this unprecedented situation could mean the difference not only between getting herself or Trump into the White House—but between democracy and autocracy.

Back in New York, Harris resisted the idea that her past two years represent any sort of evolution into a stronger leadership role. So I flipped to what her longtime friend, California Senator Laphonza Butler, told me. Butler didn’t see some post-Dobbs awakening in Harris either, but she mentioned one thing she thought might be new, and I shared it with Harris: “I see a Black woman who got sick and tired of trying to please everybody and just said, ‘Fuck it. I’m not gonna make everybody happy. I just have to be me.’”

Harris responded with the trademark laugh that’s launched a thousand hateful Fox News segments and told me: “I love Laphonza Butler.”

Without anyone fully noticing it, Harris was already leading the outreach to all groups of voters—women voters, Black and other voters of color, young voters, and voters who care about gun reform—who are less than fully in the tank for the Democrats this election cycle.

Her ability to reach these constituencies has been an asset over the course of her career. “All of her strengths were always clear to me,” says Patrick Gaspard, the leader of the Center for American Progress, the ambassador to South Africa under President Barack Obama, and Obama’s political director in 2008, when Harris was a crucial surrogate. “I could send her anywhere,” he adds.

“The universe of likely voters Joe Biden would need: Women. Women in the suburbs. It was clear there would be a challenge with younger voters, which is a natural place for her. And clearly voters of color. Given all that, it was obvious she’d be a really important flag-bearer.

“All of that was absent from her early coverage. There was no sense of history.”

Harris and her team would prefer that I ignore that past coverage and look to the future, but even Gaspard admits that “the arc to a [political] story always has an up and a down.” The early coverage was harsh: For instance, a June 2021 Politico headline blared “Kamala Harris’ office rife with dissent” and claimed that the dysfunction came “from the top.”

Harris’s admirers—not staff—have given me names that I can’t share of who some of the leakers were. A few came from the White House, not the vice president’s office, my sources say. But every person I spoke with said that her detractors did not include Biden, whose appreciation and admiration for her, they say, has continued to grow since assuming office. That was more evident this spring. At a reception in the Rose Garden in May, he quipped, “I work for Kamala Harris. I asked her to be my vice president because I knew I needed someone smarter than me.”

During his commencement speech at Morehouse College later that month, Biden told the graduates: “I have no doubt that a Morehouse man will be president one day—just after an AKA from Howard.” (AKA is, of course, Alpha Kappa Alpha, the first intercollegiate African American sorority; Harris pledged AKA as an undergraduate at Howard University, one of the nation’s largest historically Black colleges and universities.) Harris has solidified a role as an emissary to crucial voting blocs: to women of every race and age—including some Republican women—because of the reproductive health crisis; to Black voters, who polls show were less enthusiastic about Biden than he could afford; and to younger voters, angered by the war in Gaza but also disappointed by what they see as inaction on the climate crisis and gun violence, as well as insufficient student loan relief. (It would be remiss of me not to point out that the latter is partially the fault of the Supreme Court, which ruled Biden’s first sweeping relief plan unconstitutional.)

It’s undeniable that Harris gained a new role—and a renewed sense of direction—when the draft of Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito’s anti-Roe decision was leaked. I was at an EMILYs List gala where Harris gave the keynote the night after the leak, and as I reported at the time, she channeled the rage in the room.

“How dare they?” Harris asked the crowd, with genuine anger. “How dare they tell a woman what she can and cannot do with her own body?”

The reproductive health crisis has also allowed Harris to reframe her career as a prosecutor (which alienated many progressives during her presidential run) in terms of her work defending sexually exploited women and girls. “I created the first child sexual assault unit in the [San Francisco] DA’s office,” she reminded me. “Remember, they used to call [underage sex workers] ‘teenage prostitutes’; I changed the name to ‘sexually exploited youth,’ and I said, ‘Instead of police picking up these kids and arresting them for teenage prostitution, we should treat it as: They’ve been exploited.’ They used to be taken to juvenile hall. Remember, I created a safe house for them.”

Harris also has a personal connection to the issue: Wanda Kagan, her best friend in high school, was physically and sexually abused by her father. Now a hospital administrator, Kagan has been telling her story since 2020, but she’s been more prominent of late. “I think she knew I was being abused at home, physically,” Kagan told me in May. “But when I decided to tell her I was being abused sexually, too, she was like, ‘You have to get out of there. You have to come stay with us.’” Harris called her mother, who immediately insisted that Kagan live with their family.

Harris has traced her desire to be a prosecutor to her early experience with her best friend’s nightmare. “I didn’t think it was my right to tell Wanda’s story,” she said, “and then she started telling it, and encouraged me. It had a profound impact on me. We were young teenagers. Maybe it’s because from the earliest stages of my life, my mother said, ‘Take care of your sister,’” referring to Maya, her only sibling, who is two years younger.

“The passion that you hear from me is: There are so many people suffering because of [sexual assault]. Many are silently suffering. I know enough from prosecuting child sexual assault cases. When we were selecting a jury, when we’d ask prospective jurors, ‘If there’s something that’s too personal that you want to bring up, we can go back to chambers,’ the number of people that raised their hand to say, ‘Can we talk about this in chambers?’” she recalled. “And we’d go back and we’d talk, and they’d never told anybody, but they’d say they cannot sit on this jury because of that issue…. They’d experienced it.”

Michele Goodwin, a professor of reproductive law at Georgetown University, was among a group of scholars Harris consulted after the Dobbs decision. “She listened, even though she clearly knows the issue and has her own ideas,” Goodwin says. Harris “anticipated all of what was at risk: interfering with interstate travel, criminal punishment for women and doctors. She wanted to dig deeper.”

Celinda Lake, a Biden pollster, agrees. “She has been very comfortable talking about the fact that reproductive justice is economics, it’s healthcare, it’s contraception, it’s maternal health, maternal mortality,” Lake says, noting that the maternal mortality rate for Black women was three times higher than for white women.

And Harris’s appeal is starting to show up in the polls. “She does better with young people, she does better with African Americans—even better than the president—and she does better with younger women,” Lake says. A Politico poll in late May showed this strength with Black voters—and reported that she was “way out ahead in a hypothetical 2028 matchup between several other figures in the party,” including Newsom, Whitmer, and Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg, as well as Arizona Senator Mark Kelly and Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro.

Harris’s outreach to African Americans is arguably as important as her role in connecting to women. Part of her strategy is touring American cities with large Black populations—including Milwaukee, Atlanta, Detroit, and Philadelphia—to promote the administration’s “Economic Opportunity Agenda.” When I traveled with her to Milwaukee on May 16, a New York Times/Siena poll had just come out showing Trump getting more than 20 percent of the Black vote nationally, more than any Republican since the 1960s.

Harris brought Deputy Treasury Secretary Wally Adeyemo and Acting Housing and Urban Development Secretary Adrianne Todman to Milwaukee to help her spread the word about the administration’s record on advancing economic opportunities among Black Americans.

Harris shared the stage with the comedian and radio host D.L. Hughley and addressed a crowd of roughly 350 small-business owners, healthcare workers, realtors, and community leaders and activists. There was a lot to discuss. While much of her pitch was aimed at businesspeople and aspiring homeowners, she and Hughley also delved into what the administration had done for those who are still trying to make ends meet. Under Biden, small-business loans can now go to formerly incarcerated people. Student loan debt can be forgiven even for students who didn’t get degrees. The administration has also mandated that medical debt be excluded from credit score calculations.

The most meaningful interaction came when Hughley apologized to Harris for believing the “media narrative” about her as a tough-on-crime prosecutor who locked up too many Black men as the San Francisco district attorney and later the California attorney general (the shorthand: “Kamala is a cop”), which helped doom her presidential bid. A January 2019 New York Times op-ed by the legal advocate Lara Bazelon had blared “Kamala Harris Was Not a ‘Progressive’ Prosecutor,” arguing that as attorney general she had failed to sufficiently support progressive criminal justice reforms and fought the release of several prisoners whose appeals made a convincing case for their innocence. But as Biden prepared to pick Harris as his running mate 18 months later, Bazelon told Politico, “She’s positioned herself in the last couple of years as someone who really is on the right side of these issues, and that carries weight.”

Hughley said onstage that he’d heard only the criticism, not the corrective: “I had let a media narrative co-opt my perspective, and I think that tends to happen with women and people of color. I had to apologize to you.”

“I didn’t want to like the prosecutor,” Hughley tells me later by phone. “It’s not cool to like a prosecutor! California had become such a mean place. I wanted to blame somebody. But then we had dinner. It was a very heated conversation, and I remember how calm she was listening to me. I was very impressed.”

In the audience, Milwaukee County Executive David Crowley was moved by the interaction. “I thought that was so powerful! You don’t get a lot of Black men apologizing publicly to Black women,” he says. (“You don’t see men apologizing publicly to women, period,” Celinda Lake adds later when I recount the story to her.)

“She got in the weeds, and we needed her in the weeds,” says Crowley, who at 38 is the youngest person, as well as the first Black person, elected as county executive. Crowley gave me a list of local initiatives that had been made possible by programs passed under Biden and Harris. “We’re making the largest push to build affordable housing in years. We’re creating opportunities for Black and brown families to become first-time homebuyers. The dollars are coming to Milwaukee: for development, housing, health equity. Black unemployment is down. We’ve broken ground on more Black businesses. More programs for seniors. We’ve also been able to save programs that were jeopardized.” These are not just talking points: Unemployment and poverty among Black Americans are at all-time lows across the country.

The influential Milwaukee radio host Earl Ingram Jr. was equally impressed. “I had never had a chance to hear directly from the vice president,” he says. “The media made her a caricature, just focusing on her giggling. It was clear to me that the first thing I have to do is reassure people who haven’t met her that she’s a bright, accomplished woman, she’s astute, she’s not what you’ve been told. I’ve gotta make sure people who didn’t see her know that.

“I’m proud to see her as my sister.”

I asked Harris what she is hearing from Black men, adding that while I didn’t believe the recent polling that said Trump could get 25 percent of their votes, I was wondering what she thinks is going on.

She asked me frostily, “What’s going on with what?”

I stumbled a bit, noting that men across almost all racial groups are more likely to vote Republican than women, but that there had been a lot of reporting lately about the ways that Trump’s message was seemingly resonating with Black men.

“Well, you’re asking a lot of questions,” Harris replied. “But let me start with this: There is a trope in this election which I take issue with, because the underlying premise suggests that Black men should be in the back pocket of Democrats. And that is absolutely unacceptable. Here’s why: Why would any one demographic of people be different from any other demographic? They all expect you to earn their vote! You’ve gotta make your case.”

“And you’re out there making the case—” I started, but she interrupted.

“You’re assuming they’re a monolith, Joan, and they’re not.”

Ouch. “I don’t think I assume that,” I told her.

“Black men are no different than white women, than Asian teenagers—go across all the demographics you can imagine. They want to talk about the economy, they want to talk about healthcare, they want to talk about small business and access to capital. Gun violence, climate. They’re no different from anyone else. Why not be shocked that white women are voting for Trump?”

I assured her that I am shocked by that.

“You know what I’m saying,” she replied. “But the narrative is for some reason focused on one demographic—honestly, in a way I find a bit insulting.”

Here’s the thing: I know Harris sees the same polls that I do. She sees the uptick in Trump’s support among Black men; that’s partly why I was invited to travel along to the Milwaukee event. She can be defensive with reporters she feels are somehow disrespecting her, but I’m a little surprised to be on the receiving end, since she knows I respect her. On the other hand, when we spoke, I understood her irritation when the most bewildering question was: How could this swindler/grifter/racist/felon arguably be leading Biden both nationally and in swing states?

Even more offensive, she said, is “the assumption from Trump that Black men liked his mug shot and his being found guilty of 34 felonies. That helps him? So you have now decided to package up in your own head the sum total of a whole population of people around some sense of connection to the fact that you’ve been found guilty of 34 felonies? It’s insulting, and he’s wrong.”

That tense exchange with Harris brought back memories of some of our spiky interactions while I was reporting a 2003 profile of her for San Francisco magazine. During her campaign for district attorney, the city’s justice system had been rocked by a series of racial conflicts. She thought I pushed her harder for decisive words on these controversies than I’d push a white candidate—and she probably was right. Nevertheless, we remain on good terms. Part of that is because of the personal connections I mentioned earlier. But most important to Harris, I think, is the fact that I’m one of the few national reporters who had a chance to interview her late mother.

Harris grew up the child of two immigrant scholars, Shyamala Gopalan, from India, and Donald Harris, from Jamaica, who met at the University of California, Berkeley. Both were political radicals (they divorced when she was 7 years old). As a New York Times article recounted, the Afro-American Association where they met was an influential center of Black nationalism; some of its members helped found the Black Panther Party. Harris recalls growing up at civil rights marches, in a home where “Free Huey” and “Free Bobby” were written on the sidewalk outside their house to protest the imprisonment of Panther leaders Huey Newton and Bobby Seale. So how did she wind up as a prosecutor?

When I spoke with her mother in 2003, she admitted that the family was surprised: “People from our background tend to be public defenders.” Even at the time, I sensed that Gopalan Harris, who became an endocrinologist and a renowned breast cancer researcher, was the most important person to talk to about Harris other than Harris herself. But I didn’t entirely get how important.

One of the criticisms Harris faced was that she was the candidate of San Francisco’s moneyed elite, many of whom she counted as friends, and they had handpicked her to challenge the progressive Terence Hallinan, whose office was in disarray. This narrative persisted at least through her presidential campaign. “How San Francisco’s Wealthiest Families Launched Kamala Harris,” announced a 2019 Politico article. “In Pacific Heights parlors and bastions of status and wealth, in trendy hot spots, and in the juicy, dishy missives of the variety of gossip columns that chronicled the city’s elite, Kamala Harris was a boldface name,” it declared breathlessly. It also called her, repeating an insulting joke, one of the “Pretty Thangs” of the political scene. It should also be noted that some of these very same social connections “launched” Gavin Newsom. Those ties dominated the coverage of Newsom’s early career but rarely came up once he became a statewide figure.

The tale all but obliterated her scientist mother, her radical economist father, and her circle of left-leaning Bay Area friends who in fact “launched” the future political leader.

Back in 2003, her mother recounted that Harris was so pigeon-toed that she wore leg braces for a while and ugly orthopedic shoes for years after. The family, she added, were academic nomads, moving from college town to college town before she and Harris’s father divorced. “I assume the divorce was very hard. I’m sure Kamala suffered. We did not have an orderly television-family life. I was always working.”

Gopalan Harris, I realized later, was trying to complicate the caricature of her beloved daughter—to refute the charge that Harris was a socialite to whom everything had come easily.

Watching Harris over two months, I noticed how constantly she mentioned her mother’s influence on her life and career. In our interview, she described how her current campaign on reproductive justice originates with that. “It’s grounded in having a mother who was one of the very few women of color as a research scientist on one of the biggest health issues that women face, which is breast cancer. And how she fought so passionately and brought that fight home, in terms of the importance of fighting for women in the healthcare system and fighting for their dignity.”

And that laugh her critics like to mock? That comes from her mother too. “I have my mother’s laugh,” she told Drew Barrymore during an April appearance on her talk show. “I grew up around a group of women who laughed from their bellies! They’d sit around the kitchen drinking coffee, telling big stories with big laughs. I’m never gonna be one of those people who—” She tittered softly into her hand. “I’m not that person.”

Undeniably, the toughest issue that Harris faces on the campaign trail is the war in Gaza, which took a huge political toll on Biden’s standing with younger voters. She has gotten credit for being a step ahead of the president, most notably in early March, when she addressed a crowd commemorating “Bloody Sunday” in Selma, Alabama. “What we are seeing every day in Gaza is devastating,” Harris said. “We have seen reports of families eating leaves or animal feed. Women giving birth to malnourished babies with little or no medical care, and children dying from malnutrition and dehydration.”

Citing a recent incident when dozens of Palestinians rushing to get food aid were killed by Israeli forces, Harris continued: “People in Gaza are starving. The conditions are inhumane. The Israeli government must do more to significantly increase the flow of aid. No excuses…. There must be an immediate ceasefire for at least the next six weeks, which is what is currently on the table.”

But the eloquent anguish in Harris’s words sits uneasily alongside the administration’s actions. Biden has been essentially unyielding in his military support for Israel, even as the death toll in Gaza climbs ever higher and the global condemnation of the war deepens.

Harris doesn’t set the administration’s foreign policy agenda, and it’s unclear how much she has pushed internally for Biden to shift course on Gaza. In public, though, her team has been eager to play down any notion of daylight between her and the president. “The difference is not in substance but probably in tone,” one of her advisers on the conflict told me.

I asked Harris about that question of tone.

“Listen, I strongly believe that our ability to evaluate a situation is connected to understanding the details of that situation,” she said. “Not speaking of myself versus the president, not at all. From the beginning, I asked questions. OK, the trucks are taking flour into Gaza. But here’s the thing, Joan: I like to cook. So I said to my team, ‘You can’t make shit with flour if you don’t have clean water. So what’s going on with that?’ I ask questions like, ‘What are people actually eating right now? I’m hearing stories about their eating animal feed, grass….’ So that’s how I think about it.

“Similarly, I was asking early on, ‘What are women in Gaza doing about sanitary hygiene? Do they have pads?’ And these are the issues that made people feel uncomfortable—especially sanitary pads.”

The young people who have mobilized against the death and destruction in Gaza are unlikely to be mollified by these answers. What does she say to them, I asked?

“They are showing exactly what the human emotion should be as a response to Gaza,” Harris replied. “There are things some of the protesters are saying that I absolutely reject, so I don’t mean to wholesale endorse their points. But we have to navigate it. I understand the emotion behind it. We want and have called for a ceasefire; the ball is now in Hamas’s court. For all those who want to see a ceasefire: Join us in calling for Hamas to take the deal so we can have a ceasefire, get the hostages out, get aid in, and start working for a two-state solution, which I’ve been advocating for practically since October 8.”

But the day after our conversation, there was reliable reporting that Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, not just Hamas leaders, opposed the terms of the ceasefire deal. The story would flip many times before I finished this piece.

Harris said that her approach to young people is consistent. “There are so many issues impacting Gen Z,” she said. “They’ve only known the climate crisis. I ask in every venue, ‘Raise your hand if at any point between [grades K-12] you had to endure an active shooter drill.’ Almost every hand goes up. We grew up with fire drills. These kids are afraid that somebody’s gonna bust through the classroom door with an assault weapon. They witnessed the killing of George Floyd. During the height of their reproductive years, the highest court of the land took away their right to make decisions about their own bodies. They have endured so much.”

Harris is less afraid that young voters will go for Trump than that they’ll stay home in November. “You’ve got, on the one side, an administration in Joe Biden and me fighting for a woman’s right to make decisions about her own body, your right to love who you love openly with pride; on the other side, someone who took away a fundamental right, his allies who promote ‘Don’t say gay,’ want to take away contraception, IVF,” she said. Trump will also roll back the administration’s moves on climate protection, student loan relief, and gun safety reform, she has pointed out. “Don’t let a situation or circumstance silence your voice,” she tells young voters.

Harris has worn a lot of hats in the administration, most importantly that of president of the Senate, where she has set an all-time record casting tiebreaking votes for Biden’s priorities and appointees. She chairs the White House Office of Gun Violence Prevention, and its executive director, Greg Jackson, talks about the work she’s put in behind 40 executive orders and two new laws on gun safety reform.

At a recent campaign event, Jackson recalls, Harris “took an hour out in advance to talk to elementary and middle school youth impacted by gun violence,” meeting with them privately. “She’s met with hundreds of survivors,” he adds—including, in June, some high school seniors whose graduating class was decimated by the massacre of 20 first-grade classmates in Sandy Hook, Connecticut, in 2012.

Harris also chairs the White House Task Force on Worker Organizing and Empowerment, as well as the National Space Council. “Please don’t forget about that, because I’m really excited about it,” she said to me, proud of her work with global leaders on the Artemis Accords, committing a global coalition to common principles to guide space exploration, including sharing scientific data. The initiative seeks to place a woman, a person of color, and the first international astronaut on the moon this decade.

She has also stepped up her international profile in the past two years. Since her inauguration, Harris has visited 21 countries and met with 150 world leaders, according to her office. She is proud of her historic visit to Africa in 2022, where she was greeted by thousands of ecstatic people in Ghana. But not only the visit, she told me.

“It’s about reframing our relationship with the continent of Africa and beginning the next era in a way that is about a partnership, not about aid,” Harris said. “Recognizing that by 2050, one in four people on Mother Earth will be on that continent. The median age is 19. My goal is to change the narrative about what should be the relationship between the US and Africa.” She’s proud of a public-private partnership she’s led that’s already raised over $8 billion for investment there.

Lake, the pollster, argues that even before the Dobbs decision, Harris’s Africa visit reset some of her media coverage. “She registered as a major leader,” Lake says. “Women have to have validators for our leadership [to be taken seriously]. When all of those foreign leaders were so respectful of her, people were like, ‘Oh, she’s not just cutting ribbons.’”

Still, Harris faces media headwinds here in the United States. She has represented the country three times at the Munich Security Conference, but I watched this past February as major cable networks cut away from her remarks there, which included new details about US policy on Gaza, in order to announce the death in custody of the Russian dissident Aleksei Navalny. That may have been defensible news judgment, but the networks returned to Harris’s remarks only briefly, then shifted away.

Where did they go instead? To covering the ludicrous hearing in Fulton County, Georgia, where Republicans were trying to disqualify the district attorney, Fani Willis, from prosecuting Trump because of her romantic relationship with another lawyer working on her team. It was hard to ignore the message: The American media is far more interested in covering Black women when it involves alleged scandal or lurid claims about their romantic lives. The Black woman leading on a global stage at a moment of crisis, from Russia to Gaza to our own threatened democracy? Not so interesting.

As the relentless speculation about whether Biden would head for the exit picked up after his first debate performance, so did the chatter about an alternative.

The vice president’s admirers have been outraged by the media’s continuing to promote alternatives to Harris for 2024. Polls show even the familiar governors Newsom and Whitmer with single- or low-double-digit support among Democratic voters as the 2028 nominees, while Harris continues to strengthen, with 42 percent in recent polls. Even after Biden’s withdrawal, some Democrats have continued to point to alternatives, saying that Harris’s polling is weak. “If [42 percent] is weak, give me weak,” Lake says.

It’s also worth noting that Harris, as part of the Biden ticket, is the only candidate who would have easy access to the Biden-Harris campaign committee’s funds, which in late May totaled about $91 million of the approximately $240 million all Democratic groups together have raised for the campaign. Also, as the longtime Democratic strategist Donna Brazile asked CNN, “How the fuck are you going to put all these white people ahead of Kamala?”

Oh, and the notion that the Democrats should have an “open convention” to replace Biden? First, the president would have to release his delegates, which would trigger chaos. “Have you met us? We’re Democrats!” retorts Leah Daughtry, a party leader and the CEO of past Democratic national conventions. “We would have the food fight of the century!”

“Food fight” is probably an understatement.

Though my interview with Harris preceded the debate, concerns about Biden’s age and fitness had been swirling for years. But I didn’t bother to ask her about the speculation over whether Biden should remain at the top of the ticket—I didn’t want to face her prosecutor’s glare. Instead, I took a different risk and asked her about the perceptions that she’s become more comfortable in her job, maybe even having some fun, which I acknowledged was a tough concept in a time of war and the threat of Trump. Harris did not entirely shut me down.

“Remember, we came in during Covid,” she said. “[Only] Joe Biden and I and a couple of staff could be together in person. We were spending day and night trying to convince people to get vaccinated, spending day and night trying to get checks out to people. Remember the number of women who left the workforce? It was about a full year and a half of trying to get our country back on track.

“And also, we just couldn’t travel! Now I’m on the road, and I love getting out of DC—I’m telling you, get me out of DC every day of the week! I wanna be with people. I wanna be listening to them. I’m doing a lot more of that—I do enjoy that. But the work that we did in the beginning was necessary work.”

That increasing comfort in the role was evident throughout the time I spent reporting on her. Maybe my favorite moment trailing Harris this spring and summer came when she appeared on Sherri, thedaytime talk show featuring Sherri Shepherd, a veteran of The View. Many in the audience of mainly Black women were Harris’s AKA sisters, dressed in the sorority’s trademark pink and green. That’s where I met her friend Wanda Kagan, who spoke on the show not only about her high school trauma but about the school dance troupe, Midnight Magic, at Montreal’s Westmount High (Leonard Cohen was also a graduate), where Harris moved with her sister when their mother got a job at the city’s Jewish General Hospital.

Kagan and I could see Harris dancing in her seat and singing along with the music boomed by a DJ during commercial breaks—she knew all the words to George Clinton’s ’80s funk anthem “Atomic Dog”—but she reined herself in when the cameras returned. “She wouldn’t really dance, but she really wanted to,” Kagan chuckled. About a month later, though, Kagan saw her friend dance at a White House Juneteenth reception after Harris was beckoned to the stage by the gospel superstar Kirk Franklin.

Daughtry, who was there, recalls watching Franklin lead Harris onto the stage: “You could almost see her thinking: ‘Do I go up or not go up?’ She didn’t have a choice. For her to refuse would say something. People there loved it. The crowd was roaring!”

Kagan loved it too. She sees Harris finally embracing all of who she is. “She has always been a compassionate, empathetic person—with power—who fights for the rights of people. Then there’s the professional side. Then she’s quirky and she’s fun and she loves to dance. I just love seeing it all come together: the power, the passion, and the funny.”

Gaspard, of the Center for American Progress, sees a lot of the same things: “Authenticity is so important to voters. People have to know they’re seeing who you really are.” He adds, “Sometimes history comes running at you and you have to be ready. She has demonstrated that she’s ready.”

Can Harris hold on to her authenticity, cement her nomination, win back the voters who had gone cold on Biden, and keep Trump out of the White House? Strap in. We’re about to find out.

More from The Nation

Donald Trump Is the Authentic American Berserk Donald Trump Is the Authentic American Berserk

Far from being an alien interloper, the incoming president draws from homegrown authoritarianism.

If Democrats Want to Reconnect With the Working Class, They Need to Start Listening to Unions If Democrats Want to Reconnect With the Working Class, They Need to Start Listening to Unions

The Democrats blew it with non-union workers in the 2024 election. Unions have a plan to get the party on message.

What Was the Biggest Factor in Kamala Harris’s Defeat? What Was the Biggest Factor in Kamala Harris’s Defeat?

As progressives continue to debate the reasons for Harris's loss—it was the economy! it was the bigotry!—Isabella Weber and Elie Mystal duke out their opposing positions.