What the Noam Chomsky–Jeffrey Epstein E-mails Tell Us

Chomsky has often suffered fools, knaves, and criminals too lightly. Epstein was one of them. But that doesn’t mean Chomsky was part of the “Epstein class.”

Noam Chomsky delivers a speech in the Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe, Germany, on May 30, 2014.

(Uli Deck / picture alliance via Getty Images)Over his long life, Noam Chomsky—who turned 97 this month—has suffered fools, knaves, and hangers-on, both the curious and criminal, too lightly.

Chomsky earned a reputation early in his career as someone whose door was always open—who talked to anyone who knocked and answered any letter delivered. Then came e-mail.

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where Chomsky taught from 1955 to 2017, was an early adopter of electronic communication, and he received his first e-mail address, [email protected], around 1985. The stream of letters Chomsky received was largely replaced by a torrent of e-mails. But Chomsky’s open-door policy continued. He still felt obligated to answer all, or nearly all, the people who wrote him, a habit that has been the subject of many a Substack column and Reddit forum.

I wrote Chomsky cold in the early 1990s, and within a week, I was in his Cambridge office. We spent an hour discussing Iran-contra and death squads, and before I left, he gave me his “secret” e-mail address, [email protected], which, as it turned out, wasn’t so secret. He gave that address to everyone anyway.

Chomsky stayed engaged no matter how tedious and repetitive his interrogator might be. In 2015, author Sam Harris badgered the then–86-year old Chomsky for five days with question after question related to defining terrorism. Chomsky did his best to answer, seemingly to no avail. He even reluctantly agreed to publish the exchanges, though he said that he thought the “publishing personal correspondence is pretty weird, a strange form of exhibitionism.”

Chomsky hasn’t spoken in public or to the press since June 2023, after he was silenced by a stroke. But his communication habits have been in the news recently—because documents, recently made public, reveal his years-long communication with the late pedophile Jeffrey Epstein. Chomsky, to be clear, has not been implicated in any of Epstein’s crimes. Rather, he seems to have been one of the many marquee names Epstein cultivated over the years.

The news has, understandably, shocked many. Chomsky’s criticism of the power elite seems inconsistent with his friendliness with Epstein, who has come to embody that elite in all its rottenness. And Chomsky’s long-standing criticism of Israel’s occupation of Palestinian land likewise appears to clash with his willingness to associate with someone many thought to be close to, if not an intelligence asset of, Israel. Tunnel focused on geopolitics and on crimes of state, Chomsky apparently didn’t see what others saw clearly: that Epstein was a pimp servicing a privatized global aristocracy, and that his victims were children.

Chomsky’s authority comes not only from his command of linguistics, a field he revolutionized, but also a perceived integrity, a sense—confirmed as true by all close to him—that he has lived a life of self-denial in service to justice. He has given an incalculable quantity of his time, and from what I understand, a good deal of his money, to people trying to make the world a better place (he has also, excessively in my opinion, indulged more than a few leftists looking to bask in his glory).

In 1970, he lectured at Hanoi’s Polytechnic University, a building half-destroyed by US bombs, and then went on to tour refugee camps in Laos. He also lectured in 1985 in Managua, Nicaragua, during Ronald Reagan’s contra war, and then in the West Bank in 1997. In 2002, he arrived unannounced in Istanbul to stand side-by-side in court with his Turkish publisher, Fatih Tas, who was being prosecuted for publishing Chomsky’s essays, including on Turkey’s repression of its Kurdish population. The state prosecutor dropped the charges rather than agree to Chomsky’s insistence that he be listed as a codefendant.

Noam was married to his first wife, Carol Chomsky—herself an influential scholar in the field of linguistic pedagogy—for 59 years. After Carol died in 2008, the inhabitants of two Colombian Andean villages, Santa Rita and La Vega, named a forest after her, El Bosque Carol Chomsky, in appreciation of her husband’s advocacy on their behalf in the fight to protect water rights. In August 2012, it took Noam two days traveling by jeep and on horseback to reach the high woods to attend the dedication ceremony. He sat in silence as villagers described violence, land theft, and water poisoning they suffered at the hands of ranchers, death squads, and gold miners. Chomsky tried to speak but couldn’t find the words. Later, he sent a note to the communities saying that he hoped that “Carol’s spirit” would help them fight the “predatory forces” they face.

And, throughout all of this time, Chomsky spoke to everyone. In 2004, he let the comedian Sacha Baron Cohen, posing in character as Ali G, into his office and patiently and obliviously answered a series of absurd questions:

Ali G: So how many words does I gotta know to be, like, proper clever?

Chomsky: “Well, the average person knows tens of thousands of words, but it’s not really about the number…”

Ali G: (interrupting) “Tens of thousands? Dat’s a lot! Me probably only knows about… three thousand. Is dat why me ain’t a professor yet?”

Chomsky: “It’s not just vocabulary. It’s how you use it, the structure…”

Ali G isn’t the most obnoxious questioner Chomsky has faced, yet I know of no instance of Chomsky refusing to finish an interview.

Chomsky is an unwavering free-speech absolutist. His belief that no speech, however vile, should be silenced got him in trouble in 1969 when he insisted that Walt Whitman Rostow, an architect and enthusiastic defender of the war in Vietnam, be allowed to teach at MIT. The university, Chomsky said, had to remain “a refuge from the censor.”

Friends and colleagues who, on other matters, remained Chomsky’s lifetime allies, including Howard Zinn and Louis Kampf, thought otherwise. They weren’t protesting Rostow’s “speech,” they said, but his war crimes. Chomsky’s defense of Rostow took place at a moment when MIT students were exposing their university as little more than an R-and-D division of the Pentagon, receiving more than half its budget from government defense contracts. Some suggested that Chomsky’s position on Rostow’s hire had more to do with protecting the university’s ties to the defense industry than with free-speech principles. As far as I know, Chomsky never changed his opinion on Rostow’s right to join MIT’s faculty.

All of this is to say that, given his inability to gate-keep himself, it is not surprising, especially considering the close connection MIT had with Epstein, that Chomsky found himself in Epstein’s orbit.

Between 2002 and 2017, Epstein donated $850,000 to MIT and visited the university numerous times. Some senior administrators knew that Epstein, in Florida in 2008, had pleaded guilty to state charges of soliciting prostitution from a minor. But they took his money anyway and kept inviting him back to campus. It is not known how or when Chomsky and Epstein first met, although the e-mail correspondence we’ve seen between them started in 2015.

MIT had long leveraged Chomsky’s reputation to build its brand. Chomsky has criticized some of MIT’s financial patrons, especially David Koch, but he still occasionally participated in “prestige draws,” lectures or symposia organized by the university meant to develop a network of wealthy donors, like Epstein. Chomsky was one of the “beautiful minds” whom Epstein would target for inclusion in his friends’ group; perhaps the two men met at one of these MIT-sponsored events.

Before his stroke, Chomsky told reporters that he had “met occasionally” with Epstein, including once in March 2015 with Martin Nowak, a Harvard biologist, and other unidentified scholars at Nowak’s office to discuss Epstein’s continued funding of a study headed by Nowak. Around this time, the e-mails show, Epstein brokered a private meeting between Chomsky and former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak. Chomsky has said that he took this meeting because he wanted a firsthand account of why talks broke down between Palestinians and Israelis in Taba, Egypt, in January 2001. The meeting seemed to confirm for Chomsky that it was Barak who ended the talks, under pressure from domestic forces in Israel.

I don’t know what Chomsky knew, if anything, about Epstein’s child sex trafficking network. Nor do I know what Chomsky knew, if anything, about Epstein’s role in advancing Israeli interests in the United States, including aiding Alan Dershowitz’s campaign to discredit John Mearsheimer and Stephen Walt’s The Israel Lobby and to paint the authors as antisemites. The most active years of his correspondence with Epstein were 2015 and 2016, when Virginia Giuffre’s civil suits against Ghislaine Maxwell, Epstein’s since-jailed accomplice, and Epstein’s friend Alan Dershowitz were getting some notice (though that story mostly went quiet after Giuffre settled out of court).

The directionality of the correspondence is nearly entirely Epstein to Chomsky, with, as far as I can tell from the searchable databases, all of Chomsky’s e-mails being replies to e-mails first sent by Epstein. The last known e-mail that Chomsky sent to Epstein in reply to an e-mail Epstein sent him was on December 26, 2016. The topic was the recently elected Donald Trump.

Chomsky’s second wife, Valeria Wasserman Chomsky, independently established her own epistolary with Epstein. (On January 22, 2017, she wrote Epstein an enthusiastic e-mail wishing him a happy birthday.) And Chomsky must have contacted Epstein in some form in 2018, given that a bank-transfer record found in Epstein’s papers dated March 28, 2018, related to the dispersal of $270,000 to Chomsky. The money was Chomsky’s—he had requested that Epstein help him complete a difficult transaction relating to his late wife’s estate. Chomsky’s original request isn’t in the public papers.

Between 2015 and 2019, Epstein extended multiple invitations to the Chomskys to socialize. Most came to naught, though the couple did attend some Epstein-organized events, including a dinner with Woody Allen and his wife, Soon-Yi Previn. Some of those gatherings pulled together political and intellectual curiosities and economic elites. But there were also figures from the political extremes, including Steve Bannon; a picture of Chomsky and Bannon was among the materials found in the recently released files.

More important to Chomsky would have been the scientists Epstein collected. At MIT, Chomsky developed a reputation for splitting his attentions, building his linguistic models around interdisciplinary scientists who brought together biology, evolution, linguistics, computation, and math, and his political critique around humanists. Bannon wouldn’t be the worst person he ever huddled with, as one observer noted that at MIT, he divided his time between the “war scientists” and the “anti-war students.”

Though Chomsky corresponded with Epstein occasionally, he was often treated as an object of fascination by Epstein and his other correspondents. “Really impressive,” Ehud Barak wrote Epstein after his meeting with Chomsky. “Brilliant guy,” Linda Stone, a former VP at Apple and Microsoft, said in one of her e-mails to Epstein.

Joscha Back, a German-US AI researcher and prominent edgelord in “transhumanist” and “effective altruism” circles, was another Epstein correspondent. In one message, after peddling a noxious bit of race and gender science that “black kids in the US have slower cognitive development” and women mostly learn through a “motivational” system based, not like men’s on curiosity, but on “pleasure and pain,” Bach went on to say that these facts negate Chomsky’s egalitarian humanism: “it would mean that Chomsky’s life long hypothesis, that people have a special circuit for grammatical language, is wrong.”

On November 28, 2018, Julie Brown’s bombshell Miami Herald exposé broke the Epstein story open. Brown not only revealed the sweetheart deal Epstein had gotten from prosecutors in 2008. She also reported that police had identified at least 36 underage girls whom Epstein had molested or paid for sex between 2001 and 2006.

After the publication of Brown’s Miami Herald story, Chomsky went silent (as far as we know, based on the released documents). Epstein, however, continued to reference Chomsky in his correspondence with others. As Epstein grew increasingly preoccupied with containing the fallout from the Herald story, he tried to recruit Chomsky’s help, even dispatching Bannon to speak with Chomsky in Arizona, where the Chomskys had moved. But he proved unsuccessful in his effort to have Chomsky sit for an interview with Bannon, which was to be included in a never-finished documentary scripted to burnish Epstein’s image.

There exists in the released Epstein documents a truly cringey undated letter of recommendation that Chomsky is alleged to have written for Epstein. The letter has been extensively cited in the press because, unlike the e-mails, it is effusive, containing several good pull quotes. Chomsky, says the letter, considered Jeffrey a “highly valued friend and regular source of intellectual exchange and stimulation.”

I’d wager that Chomsky didn’t write this gushy letter. It sounds nothing like him. Someone should run the text through stylometry software and compare it to other references we are sure that Chomsky did personally write. My guess is that Epstein wrote the letter himself (since it portrays him exactly as he wanted to be portrayed, as a polymath of “limitless curiosity, extensive knowledge, penetrating insights, and thoughtful appraisals”). Chomsky’s name appears at the bottom of the recommendation, but only in typed form. There is no university letterhead, signature, or any log or e-mail suggesting Chomsky sent the letter to Epstein as an attachment. The unsigned document was found in Epstein’s private files. Unless future document releases prove otherwise, this letter should not be taken as evidence of Chomsky’s opinion of Epstein.

Those with grudges against Chomsky, either because they oppose his politics whole-cloth or because they disagree with a particular stand he has taken, especially related to Israel, have naturally seized on Chomsky’s contacts with Epstein. An op-ed in the Jewish Standard says Chomsky’s ties with Epstein prove his moral bankruptcy: “Legitimizing evil is what Chomsky does.”

Others on social media think Chomsky’s Epstein contacts, along with his refusal to endorse the Boycott, Divest, and Sanction movement, prove he is just a liberal Zionist. Right-wing antisemites are adding Chomsky to the ranks of globalist Mossad agents. But there’s also some considered criticism of the, to put it academically, gender dynamics of Epstein’s social network, which Chomsky entered into in the decade before his stroke.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The Epstein case isn’t Chomsky’s first scandal. Over the years, he has been accused of many bad things, including denying the Nazi Holocaust and genocides in Cambodia and Bosnia, and downplaying atrocities committed by the Syrian government. Chomsky generally dismisses such accusations out of hand. “Even to enter into the arena of debate on the question” of whether the Holocaust occurred, he once said, “is already to lose one’s humanity.”

In the past, Chomsky needed little help defending himself against charges that he was a Holocaust denier, a Pentagon shill, or an Assad apologist. If he were available for comment today, I imagine he’d respond to Epstein-related questions with considerably less patience than he showed Ali G and Sam Harris. “I’ve met all sorts of people, including major war criminals,” was his curt response in early 2023, when the first reports of his relationship with Epstein came to light.

Today, almost all of Chomsky’s old political comrades—Zinn, Lynd, Eqbal Ahmad, Grace Paley, Daniel Ellsberg, Marilyn Young, Edward Said, Daniel Berrigan, and Barbara Ehrenreich, among others—are gone. These were friends who could speak to his decency and to his uniqueness in a way that could help us understand what some think, for understandable reasons, was either an unforgivable or an incomprehensible relationship.

I disagree with Chomsky on several points, politically (his opposition to BDS) and methodologically (his disdain for Hegelian Marxism). He is stubborn and rarely admits error, qualities which, frankly, I appreciate. It makes him more of a flawed human, as our inspirations should be. And of course he has been right on so many issues: Vietnam, East Timor, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Guatemala, Colombia, Turkey, the New Cold War, NAFTA, Cuba, Chile, neoliberalism, Panama, Afghanistan, Iraq, the militarization of space, corporate power, inequality, South Africa, Namibia, Libya, global warming as an existential crisis, and, of course, BDS notwithstanding, Israel, and so on and so forth.

Yet what I’ve found most compelling about Chomsky is his contempt for bullshit, the skill with which he exposes the tautologies of the powerful men, their self-confirming arguments that they are powerful because they are good, good because they are powerful.

So for me, too, news of Chomsky’s association with someone like Epstein was a jolt, and it would have been even if Epstein hadn’t run a global pedophile ring. In 2019, after news broke that Epstein had cultivated close relationships with Lawrence Summers, Steven Pinker, and others, I snicker-tweeted: “You know who seemed to be able to work their whole, influential and rather successful career in Cambridge/MIT and not attend any of Epstein’s ridiculous salons?” Well, we know now it wasn’t Chomsky. And who knows, if more e-mails come out on the Chomsky-Epstein relationship, this whole essay may read as wrong as that tweet.

Still, Chomsky’s e-mails display none of the fawning chatter found in, say, Summers’s mash notes to Jefferey and Ghislaine, and none of the affective investment in Epstein that Anand Giridharadas dissects so sharply in a recent New York Times opinion piece, “How the Elite Behave When No One is Watching.” And he does not appear to have been co-opted by whatever access Epstein provided. Not long after he was photographed with Steve Bannon, presumably at one of Epstein’s get-togethers, Chomsky gave a speech at Boston’s Old South Church denouncing Bannon as “the impresario” of an “ultranationalist, reactionary international” movement.

That picture with Bannon is jarring, but from speaking with people who knew him better than I did, for me, the image of Chomsky’s unworldly worldliness holds. He knew much about the world’s evils, but didn’t know what Saturday Night Live was when he was invited on. He was a workaholic under constant, relentless demand—read the memoir of his longtime secretary, Bev Stohl, for a sense of what Chomsky’s everyday life was like—who assigned the royalties of his books to others at signing.

As for Chomsky’s e-mails to Epstein, they sound much like the e-mails he has sent to me, warning, for instance, during Trump’s first presidency about “the sociopathic freak show in Washington” and worried how the “poisons” Trump has “released from just below the surface are not going away.” The handful of notes between 2015 and 2016 that Chomsky wrote to Epstein contain similar concerns. In one exchange, Epstein referenced religious “fanaticism,” on “both sides,” only to have Chomsky correct him: “secular religions—nationalist fanaticism, etc.—are much more dangerous,” says Chomsky, who then goes on to complain about “mainstream academics” who hold on to “myths” of “American exceptionalism” and “Israeli self-defense” and refuse to criticize “Obama’s mass murder campaign.”

Chomsky was not a sentimental member of what Giridharadas calls the “Epstein Class.”

More from The Nation

How Online Frat Mobs Target Sexual Assault Survivors How Online Frat Mobs Target Sexual Assault Survivors

A video documenting an alleged gang rape in Florida drew a flood of harassment, threats, and doxxing

Should We Treat Political Violence as a Public Health Crisis? Should We Treat Political Violence as a Public Health Crisis?

Thinking of political violence solely as a safety issue is not enough to address the harm that follows. “The patient is the community.”

Healthcare Workers Must Continue Alex Pretti’s Fight Healthcare Workers Must Continue Alex Pretti’s Fight

Pretti was one of us. We have to carry on his struggle.

The Cartoonist, the Director, and the Sex Workers The Cartoonist, the Director, and the Sex Workers

Sook-Yin Lee’s new romantic comedy, Paying for It, explores Platonic love and prostitution.

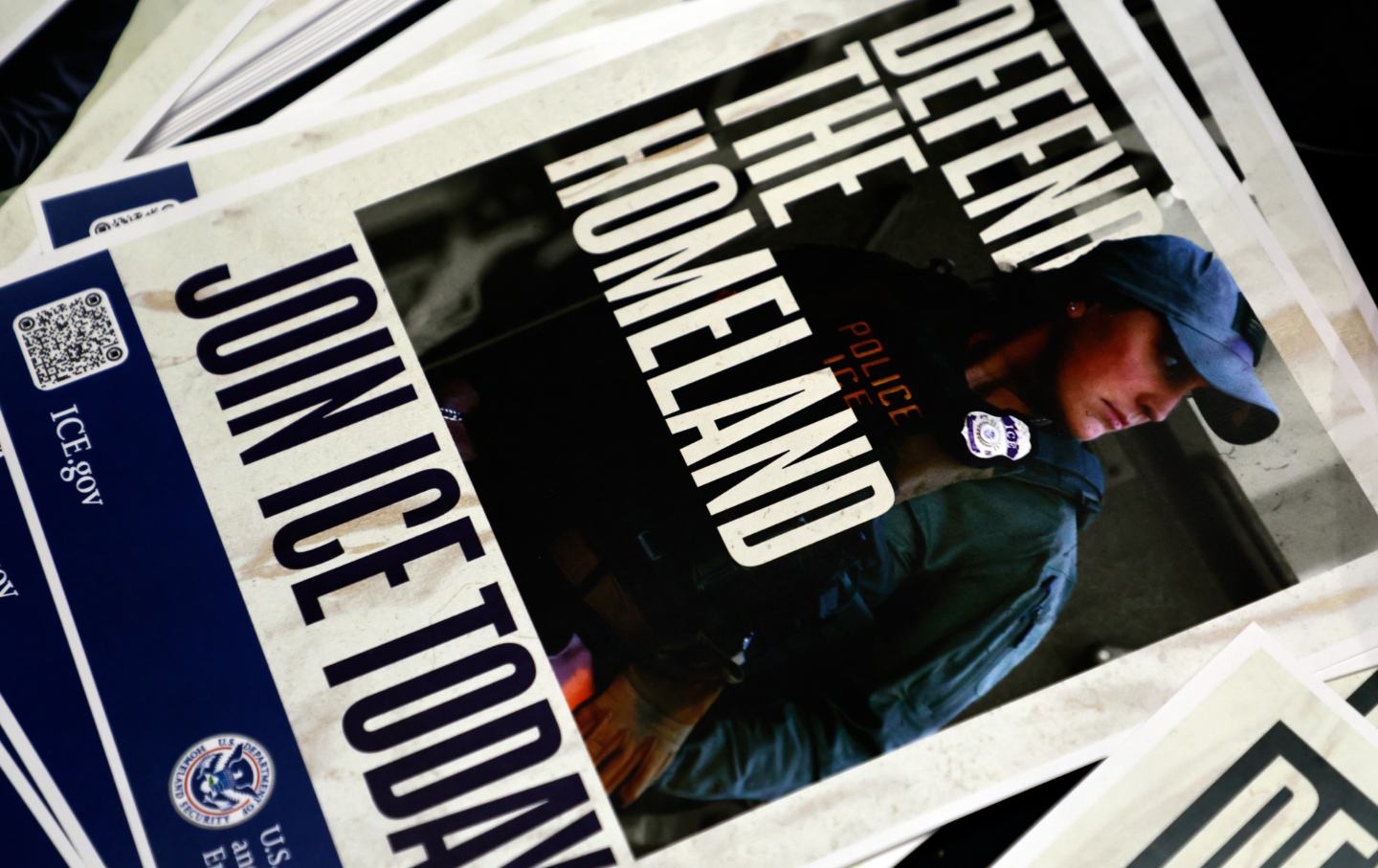

ICE’s Terror Campaign Is Part of a Long American Tradition ICE’s Terror Campaign Is Part of a Long American Tradition

As a Black man, I know firsthand how often state violence is used to perpetuate white supremacy in this country.

Whom Is ICE Actually Recruiting? Whom Is ICE Actually Recruiting?

ICE has lowered standards to facilitate a massive hiring spree. Many of the new recruits are plainly unqualified. Are some also white supremacists or domestic terrorists?