Progressives Need to Have Real Answers on Crime

California shows that unless the left acknowledges the need to make communities safe while maintaining support for criminal justice reform, right-wing demagogues will latch onto the issue.

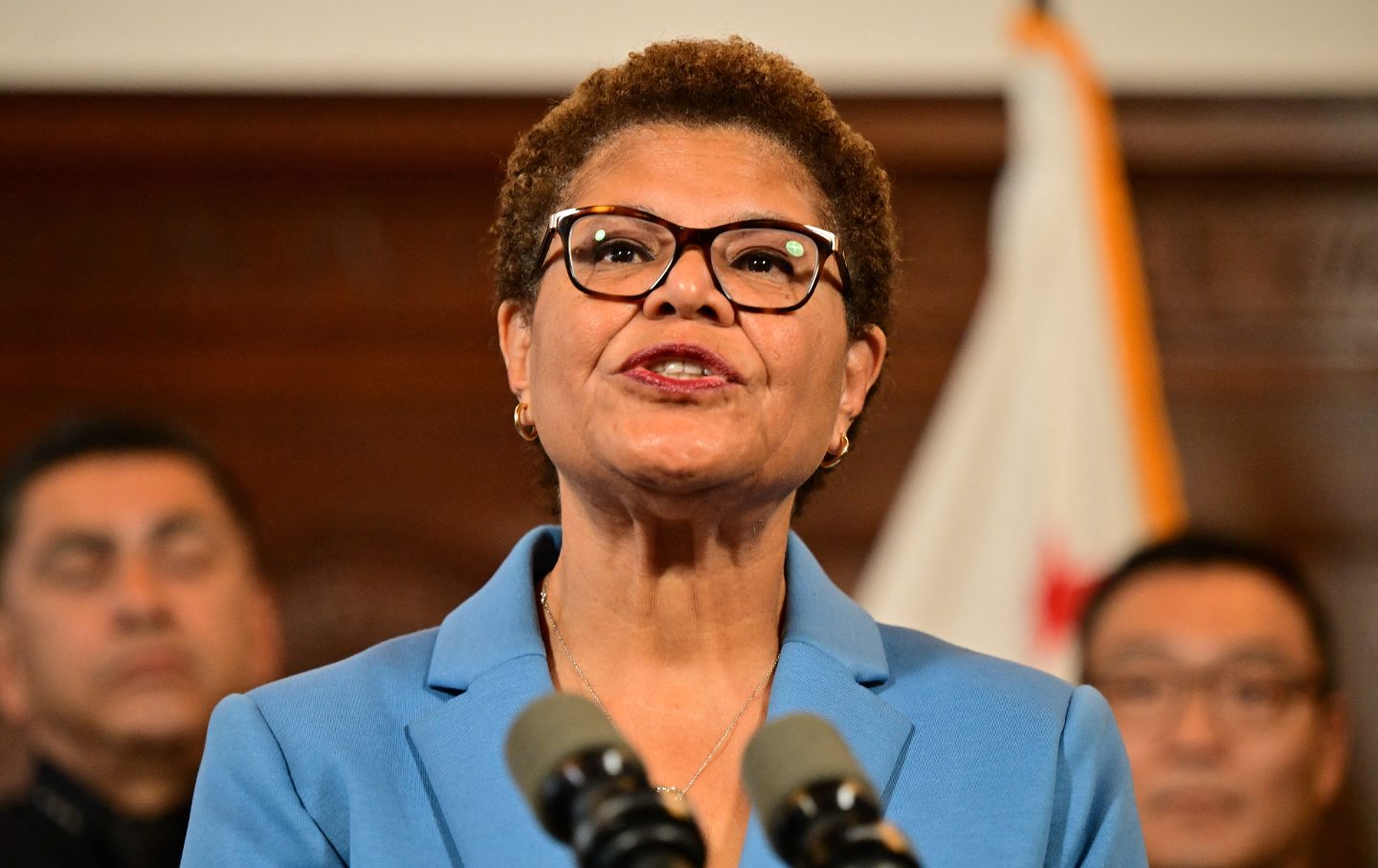

Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass speaks during a press conference to announce new efforts to curb recent retail thefts on August 17, 2023.

(Frederic J. Brown / AFP via Getty Images)Three years ago, with racial justice protests taking place across the nation in the wake of the murder of George Floyd, the Los Angeles City Council cut the Los Angeles Police Department’s budget by $150 million. While some of that savings was subsequently lost to increases in overtime pay for police officers, it was still an important moment—with community voices calling for law enforcement dollars to be reallocated to social services in underserved parts of the city.

Three years later, America is in a very different place in its conversation about law enforcement than it was in 2020, and so are its politicians. Late last month, LA mayor Karen Bass, who hails from the progressive wing of the Democratic Party, signed off on a four-year deal with the union representing the city’s police officers that will result in nearly $400 million more being spent on pay raises and bonuses. The annual budget for the LAPD will increase to roughly $3.6 billion by 2027.

Bass is under the same pressure as any other big-city politician in 2023. A spate of high-profile smash-and-grab robberies in retail malls in LA and other cities in California have put residents and business owners on edge. Viral videos of shoplifters have helped fuel a feeling that petty crimes are being allowed to flourish unabated. Random killings have further eroded a sense of public safety. If we’re being honest, we have to acknowledge that California does have a crime problem on its hands—which is likely why Bass has decided to make nice with the police unions.

And, while there’s no solid evidence to back up the idea that criminal justice reforms have led to this spate of crime, it’s become increasingly palatable for conservative commentators and those nostalgic for the toughest of the tough-on-crime days to blame liberals for the chaos. At least partly in response, liberal politicians such as Bass are now looking to insulate themselves from charges of being weak on crime by giving law enforcement additional resources and money.

Last month, to little fanfare, the California Department of Justice released its annual report on crime. It showed that violent crime and property crime had both risen in 2022, increasing by slightly over 6 percent, following spikes in the two previous pandemic years as well. The murder rate did fall slightly last year after two years of steep increases—though it remains nearly 24 percent higher than it was in 2017. Meanwhile, many other categories of serious crimes continued their upward jag. And yet, arrest rates have continued to fall, being 2.7 percent lower in 2022 than in 2021. (Interestingly, Los Angeles is an apparent exception to this trend; figures from this past June show a fall in a range of crimes, including a 27 percent drop in homicides, and a rise in the number of arrests.)

There seems to be a time lag in play here, though it’s a reverse of the time lag that fueled the tough-on-crime movement of the 1990s and early 2000s. In that earlier version, states like California saw massive increases in arrests, prosecutions, convictions, and numbers sentenced to long terms in prisons in the years after crime rates began to fall. The public, wedded to laws like Three Strikes and You’re Out, seemed to seek safety in bulking up the criminal justice system even long after there was no rational reason to still do so.

Today, California and many other states are a decade into a political reaction against tough-on-crime. One of the results has been less emphasis on law enforcement even after crime rates—especially violent crime rates—have begun rising again. There is, once more, a public policy time lag in play.

Mayor Bass’s decision to ramp up police spending may, however, be one of several harbingers of a rapidly changing environment on crime and punishment, one that could portend tough times ahead for legislators and governors on the West Coast who have bet on criminal justice reforms over the past several electoral cycles. Progressive criminal justice lobbyists in Sacramento tell me that in recent months they have been on the defensive, seeking only to protect existing gains in how the state tackles crime and punishment issues, and unable to push a more expansive set of additional reforms.

Dig below the surface, and, after more than a decade in which a majority of Californians embraced progressive criminal justice system changes, Californians’ attitudes on crime and punishment seem also to be shifting in a significantly more conservative direction. A poll late last year by the Public Policy Institute of California found that two in three Californians regard violent crime and street crime as a problem, and nearly one-third regarded it as a major problem. That was up considerably from the numbers pre-pandemic. Recently, the home security company Safewise released a report showing that 62 percent of Californians feel worried about their safety on a daily basis—a number far higher than that reported by residents of many other states, and, again, a huge increase over pre-pandemic numbers. Another poll from last year found growing support among voters to modify the terms of Prop 47, the landmark initiative from 2014 that retroactively reduced a number of felonies to misdemeanors and allowed large numbers of prisoners to be released early in consequence.

Similar polling in Oregon finds that a majority of voters now want to repeal Measure 110, which decriminalized the possession of small quantities of hard drugs, and which critics blame for a massive rise in fentanyl overdoses. Many public health experts believe that Oregon, having entirely defanged the law enforcement response to low-level drug crimes and made only limited efforts to create a treatment infrastructure, has now been left with little recourse to get addicts into recovery. (A state audit in January was supportive of the overall concept behind the measure but harshly criticized its implementation.)

In Seattle, where the police department is struggling to fill hundreds of vacant positions, there is a growing chorus of anger about street crime and random acts of violence.

Perceptions are important, and there is an increasing perception in California and the other Pacific states that the streets are becoming less safe.

In the 1980s and early ’90s, fear of crime shifted California politics in a deeply reactionary direction. Absent strong, progressive leadership on the crime issue—leadership that fully acknowledges the need to make communities safe while also working to address many of the inequities that contribute to crime in the first place—it’s a sure bet that right-wing demagogues will latch onto this theme in the upcoming election cycles. Given that political reality, it’s really no surprise that Mayor Bass has decided to channel $400 million more into her city’s police department.

More from The Nation

Deportation and the Silence That Follows Deportation and the Silence That Follows

When ICE abducted my father without cause, something strange filled his vacancy.

On Cora Weiss (1934-2025) and Peace On Cora Weiss (1934-2025) and Peace

Cora Weiss died in December at age 91. She never stopped campaigning to save the world from nuclear destruction.

The Media’s Coverage of the Venezuelan Coup Has Been Dreadful The Media’s Coverage of the Venezuelan Coup Has Been Dreadful

War may be the health of state, but it’s death to honest journalism.

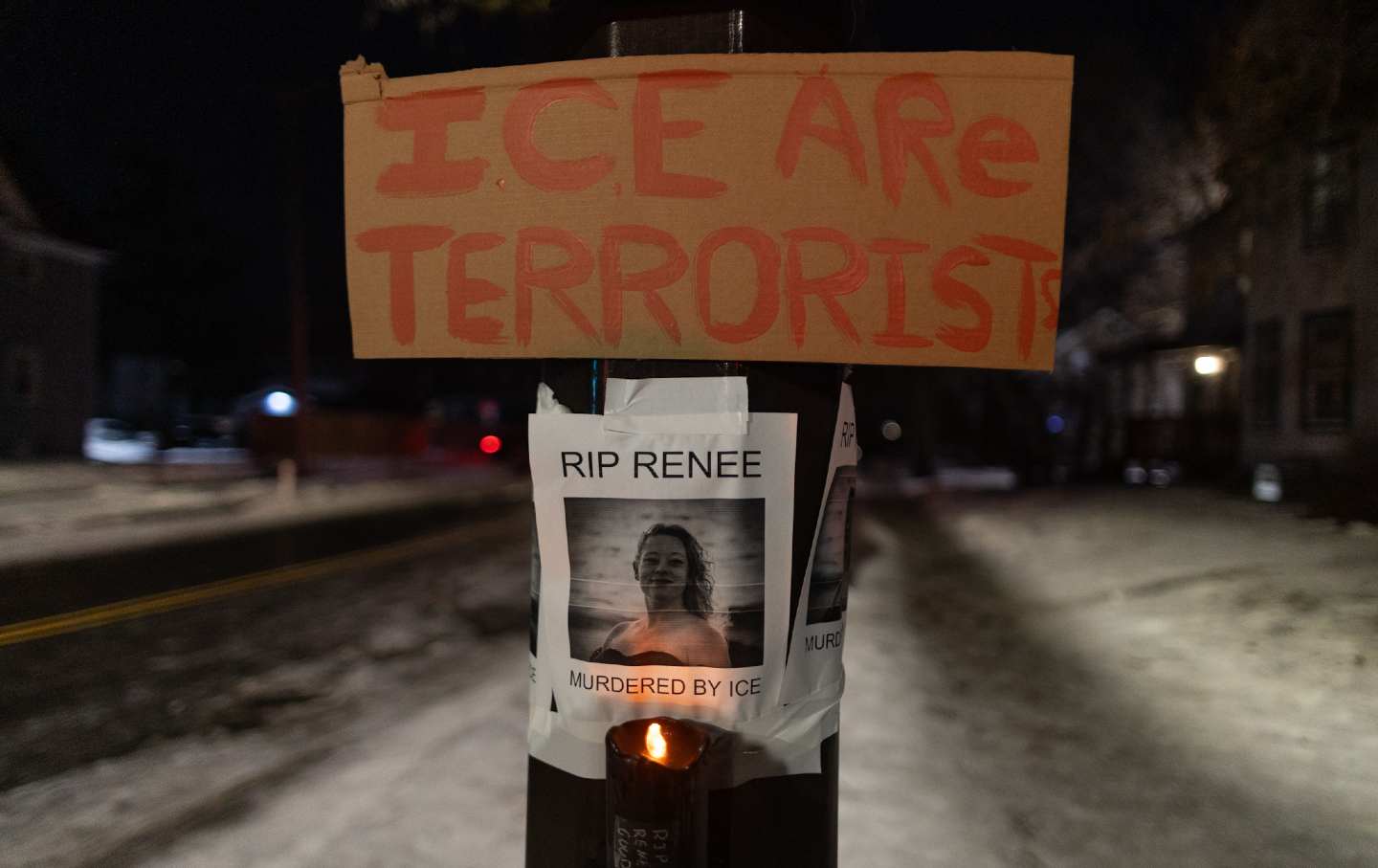

Dismantling the Meme Logic Behind Renee Good’s ICE Execution Dismantling the Meme Logic Behind Renee Good’s ICE Execution

The Trump administration is once more invoking upside-down alibis of state to conjure the bogus specter of imminent threat.

Minneapolis to ICE: Get the Fuck Out! Minneapolis to ICE: Get the Fuck Out!

An ICE agent shot dead Renee Nicole Good. Residents are ready to fight back.

Prosecute Renee Nicole Good’s Murderer Prosecute Renee Nicole Good’s Murderer

The ICE agent who killed Renee Nicole Good not only can be held accountable for murder—he must be.