Giving Black Youth a Reason to Live

Cincinnati teens are waging an uphill battle to solve the mental health crisis.

When 21-year-old Demartravion “Trey” Reed was found hanging from a tree on Mississippi’s Delta State University campus in September, the pained public outcry was immediate. The black-and-white image of the “A Man Was Lynched Yesterday” flag, which the NAACP had displayed outside its national headquarters in the 1920s and ’30s, filled my social media feeds. Rumors swirled online that the young Black man had been found with broken limbs, proof there was no way he could have died by suicide as official reports suggested. The thought of white supremacists lynching a student while the White House implemented its punishing policy goals at the federal level was too much to stomach. I heeded the advice of a trusted, Mississippi-based movement elder who urged her online community to avoid jumping to conclusions, wait for more information, and join Reed’s family in mourning this tragic loss of life.

Having studied the mental-health crisis among Black youth for the past year, I’ve seen how the public will become more outraged by the possibility of foul play than by the possibility that a young person has found life too heavy a burden to bear and wants out. Whether or not the latter is what happened to Reed, it is a devastating trend. (As of publication time, the results of an independent autopsy had not been released.) Deaths by suicide are increasing for all young people—but at a faster rate for Black children and young adults than for any other racial or ethnic group. Suicide is the second leading cause of death among Black youth ages 15 to 24. Even elementary-school-age kids are flailing. Black children 12 and younger are twice as likely to die by suicide as their white peers. This phenomenon predates the first half of this decade, when the Covid pandemic increased isolation and race-based gaps in learning. A 2023 report found that from 2007 to 2020, the suicide rate among Black youth between the ages of 10 and 17 increased by 144 percent.

The person with the largest megaphone in the current debate on the emotional and mental health of American youth is Jonathan Haidt, a social psychologist and NYU business school professor. His book The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness has become a guidebook for parents who worry that social media—and, by extension, cell phones—have colonized their children’s inner lives. But what I’ve gathered from conversations with therapists, youth development workers, families, and scholars of Black youth mental health is that Haidt’s narrow focus on screens and a bygone era of outdoor play doesn’t appropriately address what’s happening in the lives of Black adolescents.

And it’s not just Haidt. Articles appearing in mainstream news outlets tend to focus on this idea of a one-size-fits-all solution to the youth mental-health crisis, ignoring broader cultural, political, and economic forces. Young people are experiencing traumatic events that rattle their psyches and alter the shape of their lives. What’s worse, they too often feel that they have to navigate these forces alone, or that their perspectives are ignored when they do seek out help. “There’s been a lot of times growing up when I’ve been told what my needs are,” Robby Harris, a recent graduate of Ohio’s Central State University, told those of us gathered at a Black youth suicide-prevention summit in Columbus last summer. Over months of reporting, I heard repeatedly from young people and the grownups who work with them that they lack trusted adults and safe spaces where they can create and feel a sense of belonging.

Iwanted to know what was happening in Cincinnati, where I am raising a Black tween and where I know we are facing a mental-health crisis that mirrors the rest of the country’s. The Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center reported in 2023 that “the number of children and adolescents presenting to our pediatric emergency services in mental health crisis doubled” between 2011 and 2017. Cincinnati’s population is about 50 percent white and 38 percent Black, and that ballooning in admissions is driven in part by Black children. The hospital’s main emergency department sits just northeast of downtown in Avondale, a neighborhood that’s been solidly Black since the mid-20th century and was an epicenter of civil-rights and Black Power organizing and uprisings in the late 1960s.

The national data suggests gender, not just race, is a risk factor: Black boys 19 and younger are more than twice as likely as Black girls to die by suicide. That’s not to say girls are immune to the crisis: Between 2003 and 2017, Black girls’ suicide rate increased nearly 7 percent each year, more than twice the increase for boys. And Black youth who identify as queer, transgender, or gender-nonconforming are among those who are suffering. According to a recent Trevor Project survey, half of Black LGBTQ+ youth had considered suicide and 20 percent had attempted it in the previous year.

Being poor is another risk factor. “A lot of their stressors have to do with the impact of poverty. We’ve got kids rolling in here who haven’t had proper food, clothing, shelter,” longtime educator and activist Howard Fuller told me by phone. Fuller is the founder of the Dr. Howard Fuller Collegiate Academy, a Milwaukee charter school that serves middle and high school students, most of whom are Black. “Those are really important stress points in their lives.”

To better understand what’s happening in my city, I spoke with Tynisha Worthy, who cofounded and codirects a Cincinnati youth development program called Youth at the Center. When I asked Worthy what’s weighing on the minds of the Black adolescents and young adults she works with, “violence” was her first response. They’re concerned about losing access to their cell phones—and, by extension, contact with parents and the outside world—during the school day. (In the fall of 2024, Cincinnati Public Schools, like many districts nationwide, began requiring students in grades seven through 12 to lock their devices in a magnetic pouch while at school. Some students have raised concerns about not being able to access their phone during a school shooting or other emergency.) Students are also worried about the prevalence of vape pens and marijuana among their peers, Worthy said. “One of the things that caused [young people] stress…was ‘my family,’ ‘my mother,’” she continued, reflecting on the responses from participants in the workshops she’d conducted in the preceding months. (A therapist who works in local schools echoed this, citing family conflict, being saddled with adult responsibilities, and even estrangement from the family as common among her adolescent clients.) “The other stressor was school”—academic pressures—and “needing a job.”

Improving family relationships or job opportunities is outside a young person’s control, but the youth that Worthy works with are identifying what they need to feel better. Access to safe adults, therapists they can relate to, and third spaces—places to gather other than home or school—top their list.

But instead of meeting those needs, Worthy says, schools, mental-health systems, and other aspects of the city’s infrastructure are all contributing to the chronic hopelessness and feelings of being overwhelmed that are driving spikes in adolescent anxiety and depression. “We are diagnosing it as ‘The children are the problem.’ We’re saying the parents aren’t doing their part, but the larger ‘we’ are not doing our job,” she told me. What’s needed is a genuine collective effort to give Black youth a sense of joyful possibility.

The day after the 2024 presidential election, I visited Youth at the Center for the first time. The organization is located just northeast of downtown Cincinnati in the Pendleton neighborhood, an unexpected place for a program whose teen clientele is largely Black and working-class. The area is filled with the 19th-century Italianate architecture that has lured high-end developers in recent decades. Average home prices hover around $400,000 and have long been out of reach for low-income Black Cincinnatians and their Appalachian counterparts who used to populate the area.

On that early November evening, a dozen or so young people from all over the city and northern Kentucky sat at tables eating pizza and chatting before the facilitated activities began. I signed in and put on a name tag. Shawn Jeffers, the organization’s other cofounder and codirector, took a break from cheerily greeting arrivals by name and gave me a tour of the space, which is used to host and provide trainings for a range of programs, including a youth mental- health initiative called HEY!, short for Hopeful Empowered Youth, that develops strategies to improve mental health among young people in the community. White butcher paper from previous gatherings hung from the walls in the main meeting room. At the top of one piece of paper was a prompt for young people to list the issues affecting their neighborhoods and communities. Beneath were answers they had generated. Just as Worthy had told me, one theme appeared repeatedly: “shootings,” “violence,” “gun violence.”

Twice the number of teens were shot in 2023 in Cincinnati than in any other year in the previous decade. In 2022, just over a fifth of the 64 people killed in city shootings were children, and five of those victims were age 9 or younger. The local numbers reflect a national phenomenon. A 2022 study in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine found that Black youth between the ages of 5 and 17 “experienced the highest prepandemic levels of exposure and the largest increase in exposure to firearm violence during the pandemic.” For these children, “exposure to community violence can manifest as collective feelings of hopelessness, disorganized social networks, and altered social norms that can promote further violence,” the research found.

Sonali Rajan, an author of the study and a professor of health education at Columbia University’s Teachers College, has argued that exposure to firearm violence should be categorized as an adverse childhood experience (ACE), a traumatic occurrence that disrupts a child’s brain development and can change the trajectory of their life. The more ACEs a person experiences, the more likely they are to suffer a range of mental-health problems. Providing resources such as grief counseling or other forms of therapy can mitigate the long-term harm. “It’s much more effective to intervene right then and there,” Rajan told me. “This country has not invested in the resources to do that.”

Instead, when national figures weigh in on violence in Cincinnati, it’s typically to criminalize Black communities. A late-night fight in July was recorded and went viral on the right-wing account Libs of TikTok, where the blows sustained by a white man and woman were highlighted and framed as evidence of Black lawlessness. Other videos of events leading up to the melee capture the white man slapping a Black man in the face and another white man shouting racial slurs into the crowd. What’s come to be known locally as “the brawl” became fodder for national Republican figures, including Vice President JD Vance, Ohio Senator Bernie Moreno, and Ohio gubernatorial hopeful Vivek Ramaswamy, to grandstand and race-bait. This doesn’t come as a surprise given how Vance, an Ohio native and former senator, spent the campaign season stoking racial anxieties alongside President Donald Trump, making the false claim that Haitian migrants in Springfield, Ohio, were eating pets.

But when Black people are victims of state or vigilante violence (as opposed to the alleged perpetrators), these same figures are mum or distort the facts. In early May, police shot and killed 18-year-old Ryan Hinton as he and three friends fled on foot from the scene of a car chase. Days later, his father, Rodney Hinton, was accused of running a car into a Hamilton County sheriff’s deputy who was directing traffic outside a commencement ceremony. Hinton, then 38, had earlier that day viewed police footage of his son’s fatal shooting, during which the teen was shot multiple times as he fled from police. And just several months before Ryan’s death, masked neo-Nazis had descended on Lincoln Heights, a historically significant Black neighborhood, carrying guns and banners emblazoned with swastikas. The agitators hung a sign on an overpass in the community that read “America for the white man” before being escorted away (but not arrested) by police.

You might assume that a young person rattled by news of a peer’s death, the presence of gun-toting Nazis in their neighborhood, or the stress of responsibilities at home can find someone trained to give them support at school. But on average, schools have one counselor for every 408 students (the recommended ratio is one per 250) and one psychologist for every 1,127 students (the standard is one per 500), according to The Washington Post. Cincinnati Public Schools—whose enrollment is 84 percent Black—places a mental-health provider in every school, according to a 2024 report from a local public-health foundation. But that’s typically not enough.

Karisma Hazel is the CEO of Poppy’s Therapeutic Corner, a Black-owned mental-health clinic that operates in half a dozen schools in the Cincinnati area. Poppy’s staff provides therapy, working with the schools’ social workers and guidance counselors, who offer more basic interventions. There’s a long-standing assumption that Black people are suspicious of therapy and steer clear of it, but the demand for her team’s services is high, Hazel told me. “They find it as a benefit,” she said of the students, and described what her staffers hear when they walk the hallways to retrieve clients from class for a session: “‘Hey, can you come get me too? Can I be next?’”

Teenagers are eager for help, though counseling may be stigmatized in their parents’ and grandparents’ generations. During an online workshop offered by the Black Emotional & Mental Health Collective (BEAM), I learned what has happened historically in America to make many leery of trusting professionals with our stories and symptoms. In the mid-19th century, the medical director of Virginia’s Eastern Lunatic Asylum declared that enslaved Black people were immune to mental illness, because of the relative simplicity of their lives. Around the same time, the diagnosis “drapetomania” emerged as a label for the illness that was said to afflict any enslaved person who tried to escape captivity. And well into the 20th century, highly educated and celebrated white researchers and clinicians debated the size and complexity of Black people’s brains.

Today, many Black youth want a good therapist but don’t know how to access culturally responsive care, said Qeiara Manuel-Fuller, a program manager at HEY! Outside of a school setting, there’s the question of cost, and whether a session is covered by Medicaid or another form of insurance or by a family member who can pay out of pocket. The wait times are often long, and some young people can’t find a counselor who sees and supports their racial or gender identity or sexual orientation. “‘This therapist does not understand my lived experience, my culture,’” Manuel-Fuller said she hears from the youth she works with, as part of a broad coalition that includes more than 300 educators, policymakers, and healthcare providers focused on adolescent mental well-being in 12 Ohio and Kentucky counties. “‘I don’t feel connected. This person is cold. They want me to open up and tell them all these things, but they won’t tell me what their favorite color is.’”

Having a therapist who shares one’s racial background, or who at least has worked hard to understand it, is good for Black youth. So is having access to friends and classmates who are Black. It may seem counterintuitive that having class privilege can undermine well-being, but while reporting this story, I spoke with families who felt that their Black children suffered in part because they attended predominantly white schools in tony suburbs and felt racially isolated. A 2020 study on the mental health of Black youth in Ohio found that children in families with incomes greater than 400 percent of the federal poverty level were more than twice as likely as lower-income youth to experience racial discrimination. A strong relationship exists between young people’s reports of racial discrimination and their experience of mental distress.

Relatedly, there’s some evidence that students who attend Historically Black Colleges and Universities are faring better in terms of mental health. A 2025 study from the UNCF (United Negro College Fund) Institute for Capacity Building found that 45 percent of Black students who attend HBCUs report “flourishing” mental health, compared with 38 percent of those who attend predominantly white institutions (PWIs). Of those who attend HBCUs, 83 percent report feeling a sense of belonging, compared with 72 percent for Black students at PWIs. The HBCU students face significant financial stress and struggle to access mental-health services more than their counterparts at PWIs, according to the study. But on their campuses, they find a stronger sense of community and culturally relevant offerings in which they can take pride.

These findings echo the work of Jasmin Brooks Stephens, a psychologist at the University of California, Berkeley, whose work focuses on protective factors, practices that promote self-acceptance and combat traumatic stress in Black youth. In June, I drove to Columbus to see her address a statewide conference on Black youth suicide prevention. She shared research findings on interventions that help young people take pride in their culture and persist in the face of discrimination. Black youth need to know not just how to identify oppression but how to resist it, she said. They need opportunities to tell their own stories and weave narratives to counter the distortions that too often appear in media outlets.

Brooks Stephens talked about Sawubona Healing Circles, an initiative created by the Association of Black Psychologists in which Black people come together in a group setting to process grief and trauma related to their experiences. The BEAM workshop I attended also emphasized the importance of culturally rooted practices and of understanding mental health as something that’s pursued and achieved with help from others. Facilitators shared what they called a peer-support and village-care tool, which offers tips such as cooking for one another and texting reminders to take medications. The organization’s LAPIS peer-support model offers specific guidance on how someone who is not a mental-health professional can partner with a friend or loved one who is suffering to help ease their feelings of being overwhelmed. One guideline reads: “Listen to see if they are a danger to themselves or to you. If they have made a plan to hurt themselves or someone else, call an emergency hotline, your local mental health crisis unit, or trusted community members for support immediately.”

I thought of Nkosi Watts as I listened to Brooks Stephens speak about the resilience and self-acceptance that characterize Black youth who are able to maintain mental and emotional well-being or regain equilibrium after stressful periods. When I met Watts at Youth at the Center, he was 17 and part of the HEY! Initiative. The program’s participants were diverse: More than 80 percent identified as Black, Indigenous, or people of color (BIPOC). More than 40 percent identified as LGBTQ+, and nearly 25 percent had experience with the foster-care system. I was struck by how self-assured Watts was as he told me about his struggles with social anxiety and previous missteps using cannabis. I later learned that he plans to study business and psychology once he gets to college, and he’d like to do that overseas. Eventually he wants to open a Philly cheesesteak franchise here in Cincinnati, then buy a fleet of semitrucks and employ formerly incarcerated people to drive them. He’s confident and has a clear vision for his future. But life’s not perfect: He manages ADHD and sometimes struggles academically. He remembers his middle school years, at the height of the pandemic, as a time when he “got big, played video games, [and] got depressed.”

Watts has attended a highly regarded, predominantly white suburban Catholic school for boys since his freshman year and plays rugby there. That environment can be disorienting for Black students, he told me. He sees the toll it takes on some of his peers. He’s had Black classmates who can’t get comfortable there but who also can’t quite articulate why they hate the environment as much as they do. Watts thinks he knows what it is. “Something is rupturing his soul,” he said of a classmate who wanted desperately to leave and enroll elsewhere. “They act like they bring you in, but they really don’t,” he said of the school. “They use you, like as a token. It’s hard.” Watts speaks poetically of soul rupture, a phrase akin to the “spirit murder” that legal scholar Patricia Williams coined more than three decades ago to describe encounters that undermine the Black psyche and obliterate a positive sense of self.

Watts credits his relationships with his family, particularly his connection to his mother, Rashida Pearson-Watts, for keeping him on track and teaching him to be self-assured. In addition to her parenting experience, Pearson-Watts has professional training. For more than two decades, she has supported the mental-health needs of young people between the ages of 16 and 24. She takes her trauma-informed approach into churches, community organizations, and schools, including Cincinnati Public Schools’ out-of-school suspension and expulsion program. Over the years, she’s worked on HIV/AIDS education and overdose prevention and learned that hard-line, abstinence-only messages typically don’t work. So she takes a harm-reduction approach when it comes to raising Watts as well. “You’ve got to learn how to meet these kids where they are,” she told me. “They’ve seen too much. We didn’t have this phone. So to say no when the whole world is at their fingertips is not effective.”

Instead, she’s direct and moves with confidence and authority. When she noticed that her son was getting curious about girls, she left condoms on his desk, and then she and his dad followed up to see what questions he had. She said she doesn’t understand how parents can be unaware that their kids possess guns. “Where are you?” she said, exasperation in her voice. “I’ll shake Nkosi’s room up in a minute. I mean, you pay the bills!”

This level of involvement may seem heavy-handed, but many adolescents crave more guidance and guardrails, said Hazel of Poppy’s Therapeutic Corner. “You will hear a lot of them feeling that they can’t come to their parents, or they [themselves] are the adults,” she said. “I think you would be surprised by a lot of the independence that they have and a lot of the decisions that they have to make.” Pearson-Watts’s communication style may not work for every parent, but she’s on to something. Former US surgeon general Vivek Murthy and others who tend to young people in crisis say having a relationship with at least one trusted adult can shore up and protect adolescent mental health.

At Youth at the Center, I saw another one of those pieces of white butcher paper filled with visual representations of what makes for a safe adult. Cofounder Shawn Jeffers explained the images young people had drawn over the simple outline of a body: The mic in one hand meant this person amplifies youth voices. A pom-pom in the other hand meant they’re a cheerleader for youth. The bulletproof vest encasing the silhouette’s trunk signified that the adult makes young people feel safe, not by being “strict or controlling,” he said, but by offering protection.

Jeffers also told me that the youth he works with lack access to safe and welcoming places outside of home and school, or “third spaces.” As the academic year began in 2024, fights among youth had broken out at downtown’s Government Square and other city transit hubs where students transfer on their bus commutes to and from school. The police chief then appeared before the city’s school board to express alarm over the arrests of 30 youth that had taken place around transit centers since the start of the school year weeks earlier. One cause for the spike was the lack of engaging, positive after-school options for teenagers, Jeffers told me. Stores around the transit centers often posted signs in the windows barring anyone born after a certain date or limiting how many teens can enter at once. Libraries and schools don’t offer enough free, varied activities, and the city’s recreation centers often bar adolescents from their gyms and other spaces until early evening, before which the programming is geared toward elementary-school-age kids, Jeffers said.

In separate interviews, Jeffers and Tynisha Worthy echoed each other in demanding answers from the city’s leadership and institutions that claim to support the city’s teens: “Where are they supposed to go?” When Haidt urges parents to give their kids a “play-based childhood,” he seems unaware that safe outdoor spaces aren’t accessible to everyone. Or that, like most other intractable problems, the youth mental-health crisis can’t be solved by simply getting kids off screens while denying their families’ realities or what’s going on in the communities where they live.

When asked, young Black Cincinnatians regularly say they want safe and accessible places to gather, more contact with adults who will listen to and support them, and jobs. But structural barriers to well-being remain. “We know what young people have told us that they need, and we continue to give $2 million to BLINK or to fund a stadium,” Worthy told me, pointing to massive recent public expenditures for a sprawling arts festival and a soccer arena.

I thought of Worthy’s call for collective responsibility as I watched psychologist Brooks Stephens’s keynote presentation on Black youth suicide prevention last summer. One slide in particular emphasized the need for structural change in solving this crisis. It read: “In order to create a world where Black youth no longer desire to die, we need to give Black youth a reason to live.”

More from The Nation

The Future of the Fourth Estate The Future of the Fourth Estate

As major media capitulated to Trump this past year, student journalists held the powerful to account—both on campus and beyond.

Feature / Adelaide Parker, Fatimah Azeem, Tareq AlSourani, and William Liang

How a Reactionary Peruvian Movement Went Multinational How a Reactionary Peruvian Movement Went Multinational

Parents’-rights crusaders seeking to impose their Christian nationalist vision on the United States took their playbook from South America.

Hell Cats vs. Hegseth Hell Cats vs. Hegseth

Meet the military women who are fighting to win purple districts for the Democrats and put the defense secretary on notice.

Trump’s Slash-and-Burn Economy Is Devastating Black Women Trump’s Slash-and-Burn Economy Is Devastating Black Women

His administration is hitting them with “discriminate harm.”

Listen to Bad Bunny: Abolish Act 22 Listen to Bad Bunny: Abolish Act 22

An egregious tax-evasion loophole is inflaming the displacement crisis in Puerto Rico.

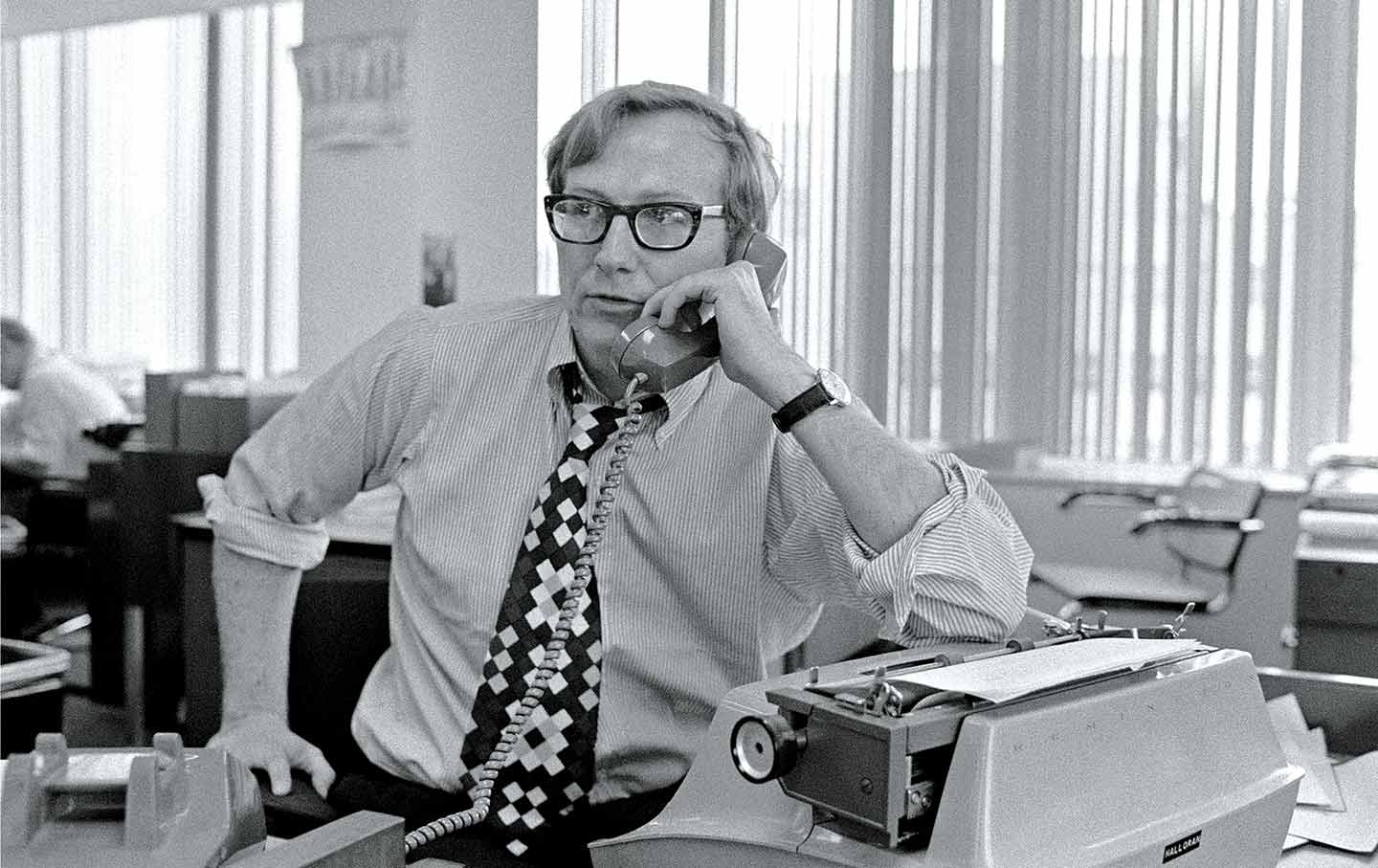

The Endless Scoops of Seymour Hersh The Endless Scoops of Seymour Hersh

Laura Poitras and Mark Obenhaus’s Cover-Up explores the life and times of one of America’s greatest investigative reporters.