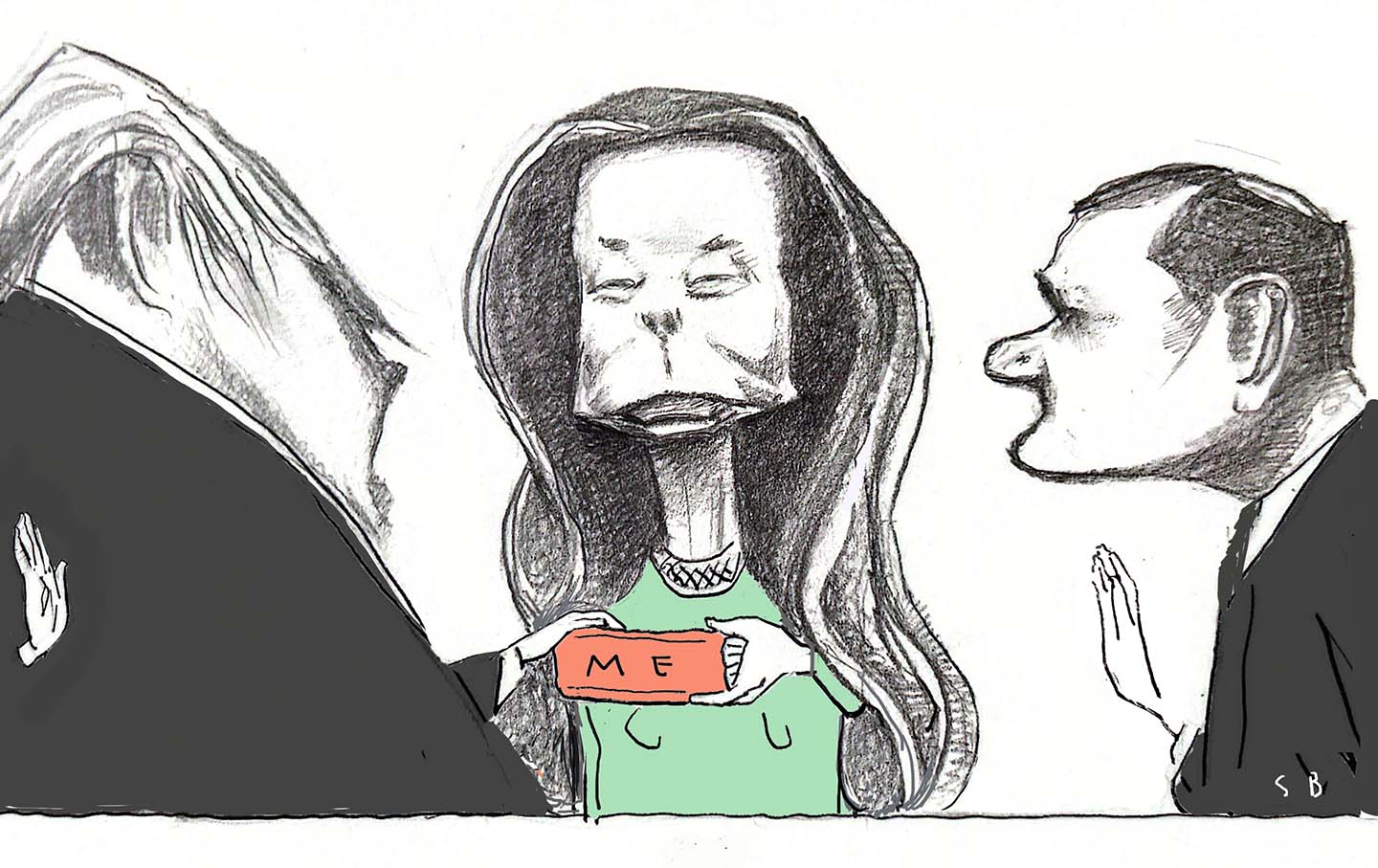

“I Always Outwork the Hate”: An Exclusive Interview With Rashida Tlaib

The only Palestinian American in Congress talks about Gaza, Biden, and how she keeps going.

Washington insiders do not approve of Rashida Tlaib. Since her election in 2018 as the first Palestinian American woman and one of the first two Muslim women to serve in the House, the Michigan Democrat has faced rebukes, condemnations, and censure. She’s been accused of everything from sympathizing with terrorists to antisemitism, mostly by Republicans but sometimes by members of her own party. Even the White House has targeted her. Yet outside D.C., and especially in her diverse Detroit-area district, Tlaib is known as a thoughtful and responsive representative with a long history of working across the lines of race, ethnicity, and religious difference. In the aftermath of the October 7 Hamas attack on Israel and the ensuing Israeli assault on Gaza, the condemnatory rhetoric has ramped up. But so, too, has admiration for Tlaib, who, with Missouri Representative Cori Bush, has emerged as the leading congressional advocate for a cease-fire. This conversation with Tlaib has been lightly edited; a shorter version appears in The Nation‘s January print issue.

—John Nichols

JN: When you started talking about a cease-fire, a week or so after the October 7 Hamas attack, that was not an easy thing to do. But, obviously, you felt it was a necessary thing to do.

RT: I just didn’t think there was any other option. I don’t think there’s a military response. I wanted to save lives, no matter [one’s] faith or ethnicity. I just kept saying that to colleagues and saying that to everyone: “Let’s save lives. The answer to war crimes is not war crimes.” I felt very strongly that there was no other option but to stop the killings.

JN: Did you imagine at that early stage that raising the idea of a cease-fire would resonate so widely, that it would inspire a mass movement?

RT: The cease-fire resolution came from the movement. Cori [Bush] and I were both approached. A number of colleagues, actually, were approached. It was Cori and I who didn’t hesitate in saying, “We’ll lead it.” I think, for myself and for Cori, who both come from community organizing and movement work, when we were called by leading organizations—Jewish and diverse other organizations that are human rights leaders in the country—we didn’t hesitate. We knew that this [resolution] was going to be used [by grassroots organizations] to organize, to give credibility to the work they’ve been doing from day one. They knew how horrific the results of the continuation of the bombings and killings, the use of white phosphorus, was going to be. When we talked, there was just no hesitation—especially when [the calls were coming from] organizations that have shown us, over and over again, that they’re coming from a place of shared humanity. We just kept pushing through with it—even as folks, including the White House, [started referring to it as] “repugnant,” calling it “disgraceful.” We kept pushing through because organizations and advocates kept our heads up high, saying, “This is the right thing to do.” And, you know, we felt it too.

JN: It must be striking for you, as a Palestinian American, to look at the polling and the energy, the demonstrations and the evidence of sympathy not just for a cease-fire, but for the very-long-neglected cause of Palestinian rights. It seems as if, in what has clearly been an awful moment, something has changed. People really are paying attention to the issues that Palestinians have long been aware of but that have not necessarily provoked mass movements in the US.

RT: What’s striking is the complete difference in the sentiment within Congress and the White House versus neighborhoods and communities across the country. When my colleagues get the knock on their door, or visits in their district offices, they’re assuming it’s going to be Arab Americans and people of Muslim faith—mostly Palestinians. And they’re taken aback when it’s the same person that comes and advocates for housing or water, or the same person that advocates for the Dreamers. It’s such a diverse array of Americans, from retirees to union leaders, coming and saying, “You need to end this. You need to support a cease-fire.” I think that’s what’s been kind of a shock to many of my colleagues, who think I’m somehow leading this movement. I say, “No, the movement is leading me, and that’s how it’s supposed to be.”

I grew up in Detroit, and I can’t express to you [how important it was] in 1990, when they replaced all of our history books to look at US history through the African American lens. It was very controversial, I remember [when the change was implemented in] my freshman year in high school, and I kid you not, it has stayed with me. [It created an] an understanding that the president of the United States is not going to wake up one day and say, “Wow, I think Black folks should have civil rights and equality.” The president or the Congress does not say, “Wow, I really think unions are important and we need to support the organizing of unions. It all happened because people marched, they boycotted, they did civil disobedience, many put their lives on the line, and it was all for human rights, for human dignity.

You see that same energy and same kind of movement right now among folks that are supporting a cease-fire. I’ve been going through what I call my “PO box” mail. There are letters from a woman in Kentucky, from North Carolina. They’re not Muhammads or Leilas; they’re Jennifers and Kenneths. I’m literally reading this: Michael from St. Louis, Ken from Pennsylvania, Peter from San Jose. I feel like I’m watching exactly that same energy that I learned about in high school—of my Black neighbors fighting, and still fighting, for human rights, for human dignity, for equality, to tell the American people that they are not disposable. So I’m not shocked—I feel like I’m in a front-row seat, watching the American people come together and show what democracy is really about. It’s movement folks, and folks on the outside, moving the consciousness of Congress. I know it’s like [walking on] tip-toe, but it is working. And I just wish it was working fast enough, because every single day we’re losing [lives] in Gaza.

JN: And yet there are efforts to silence this movement. The White House initially used the phrase “repugnant” to describe your advocacy. There was also the House censure resolution. Why do you think these efforts haven’t been successful?

RT: When my colleagues go back to their districts, they’re in complete shock, not understanding why different Americans that don’t fit the stereotype of who they think is gonna come and say, “Palestinians deserve to live; Palestinian children deserve to grow old,” are saying, “Palestinians! Palestinians! Palestinians!” And I tell [those House colleagues,] “It’s because you’re completely disconnected [from] what the American people think and want.”

The bubble of Congress and DC is real. I always knew it was there. I understood that, as somebody that was on the outside, in local politics and organizing. And now being on the inside, I can tell you the disconnect is real, and I understand why many Americans don’t feel like Congress speaks for them.

That’s why these colleagues of mine need to go home and truly listen to their constituents. The American people are telling you: “Save lives!” “Cease-fire!” “Stop funding indiscriminate bombing, the use of white phosphorus, war crimes.” I can’t tell you how many people came up to me saying, “Rashida, you’ve got to tell [President Biden] he can’t veto another UN resolution.” You can see them tearing up. These are people of Black, white, Latino backgrounds. [Our opponents] want to box us all in. They don’t want Americans coming together and saying, “It’s about time that our country leads in saving lives, not destroying and killing lives.”

JN: There’s been a growth in understanding—promoted largely by Jewish Americans—that it is not antisemitic to criticize Israel. That’s freed up the discourse, hasn’t it?

RT: For me, growing up in Detroit, I [learned] the importance of separating people and governments. I grew up in a neighborhood with 20 different ethnicities. I didn’t blame people when the government of their native land was acting in a way that is beyond their values. No government is beyond criticism. The idea that criticizing the government of Israel is antisemitic sets an incredibly dangerous precedent. And it is being used to silence the voices of those speaking up for human rights. People are so afraid in many spaces. It’s this precedent that, I think, really got us to where we’re at now: the unconditional aid, the looking the other way when the walls were built, the settlements were being built, the children were being detained, the attacks on refugee camps.

[There have been] over 10 different bombings of Gaza in, I think, 13-something years. That is what continues to lead us to where we’re at now, and I think that especially my Democratic colleagues need to understand the role that we [the United States] play here. We are literally the primary investors [in the] killing of innocent lives.

JN: You came up politically working with the Maurice and Jane Sugar Law Center in Detroit and serving as a state legislator, building coalitions with people of all backgrounds. So you arrived in Congress with an understanding, an experience, of multiracial, multiethnic, multifaith organizing that pushes beyond the boundaries of division.

RT: A Black pastor [in Detroit] taught me that our country’s not divided but we’re disconnected. I don’t care if it’s immigrant rights or water rights or demanding the protection of public education and unionization, I’ve always [understood that] power came from bringing different movement folks together.

My [allies in Detroit] know I care about every human life, no matter what faith or ethnicity. They know I would never wish violence on anyone and that my criticism has always been specifically around the Israeli government. And I think they know the coalition I had to build even just to get me elected.

I probably had less than 10 percent Arab Americans [in my district when I was elected]. I always remind young people that the majority of Americans that elected me did not share my faith or my ethnicity, and they still elected me because of our shared values.

When I was at the Sugar Law Center, it was many of my Jewish colleagues or Jewish neighbors that were ready and willing and ready to fight [alongside me] against the Koch brothers’ dumping of petroleum coke, or [Republican officials upending local democracy by imposing] emergency manager laws. [People] didn’t look around and say, “Wow, oh, she’s Muslim.” It was just so organic and it was about the issue that was at hand. I see that all the time, in every corner of my district. I don’t know if my colleagues see it in their communities. Sometimes, I wonder.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →JN: AIPAC and various other political action groups have signaled that they’ll target House Democrats who have supported a cease-fire. But my sense is that for someone like you, who’s so rooted in your district, the attacks are less likely to resonate.

RT: I always outwork the hate. I outwork the gaslighting, the lies.

I think when I got in with a margin of 899 votes [in my 2018 Democratic primary win] and made history, and my mother wrapped the Palestinian flag around me, there was a bit of a shock wave. And my second term, you saw my opponent bringing in these resources from different groups around around the country that did not want me to speak out against human rights violations or speak about in the way I consistently do when I say, “From Detroit to Gaza, justice for everyone.”

When I speak up about certain issues [in Congress], I can see around the room, in the caucus, or on the floor, that the institution I work in wasn’t ready for someone like me. Maybe me being there will make it ready for the next young woman that comes along and fights like hell to save lives, at home and abroad.

I just know that I have no choice but to continue to speak up, no matter how many times they want to censure me, police me, vilify me. I can’t just sit by, even if it’s incredibly overwhelming to be in a space where, [when] I walk in a room, my mere existence is threatening to many colleagues because, I guess, it’s reaffirming that: “Wow, Palestinians do exist.” “Wow, Palestinians are mothers.” “Wow, Palestinians care about water?” Palestinians, we do exist. We’re not going anywhere—no matter how many times they try to erase us.

JN: When the United Auto Workers union announced its support for a cease-fire, you seemed to be genuinely moved, as a member of a proud UAW family, by the show of union solidarity.

RT: My dad only had a fourth grade education when he came here. He was 19 years old. He was that guy in the corner, selling watches and watered-down perfume until he got into a plant. And then he joined the United Auto Workers, and my dad, my Baba, said the first time he ever felt human dignity was being on that line [in the auto plant]. Even though he was Muslim, even though he was Palestinian, even though he only had a fourth grade education, he was equal as a human being to everyone on that line. And the UAW did that for him. And, so, seeing his union [support a cease-fire], oh, it would have brought tears to him.

JN: What happens next?

RT: I think you’re gonna see the movement continue to grow, continue to hold the administration and Congress accountable—especially as we continue to see actions to provide ammunition and weapons and support for the genocide in Gaza. We’ll continue to see policing of me for using the words “genocide,” “apartheid.” But the truth is there—talking to NGOs, talking to the United Nations and so many others who repeat that they’ve never seen anything like this in their lifetime. We’re sitting idly by and witnessing something that we could easily, easily make a difference in and stop. I just hope the president will finally listen to the majority of the American people, especially his base—the folks, they have his back. He needs to have their back now, too.

JN: You hold out hope that the president can be moved.

RT: I have no other choice but to believe in the movement, and the American people, organizing and making him move.

More from The Nation

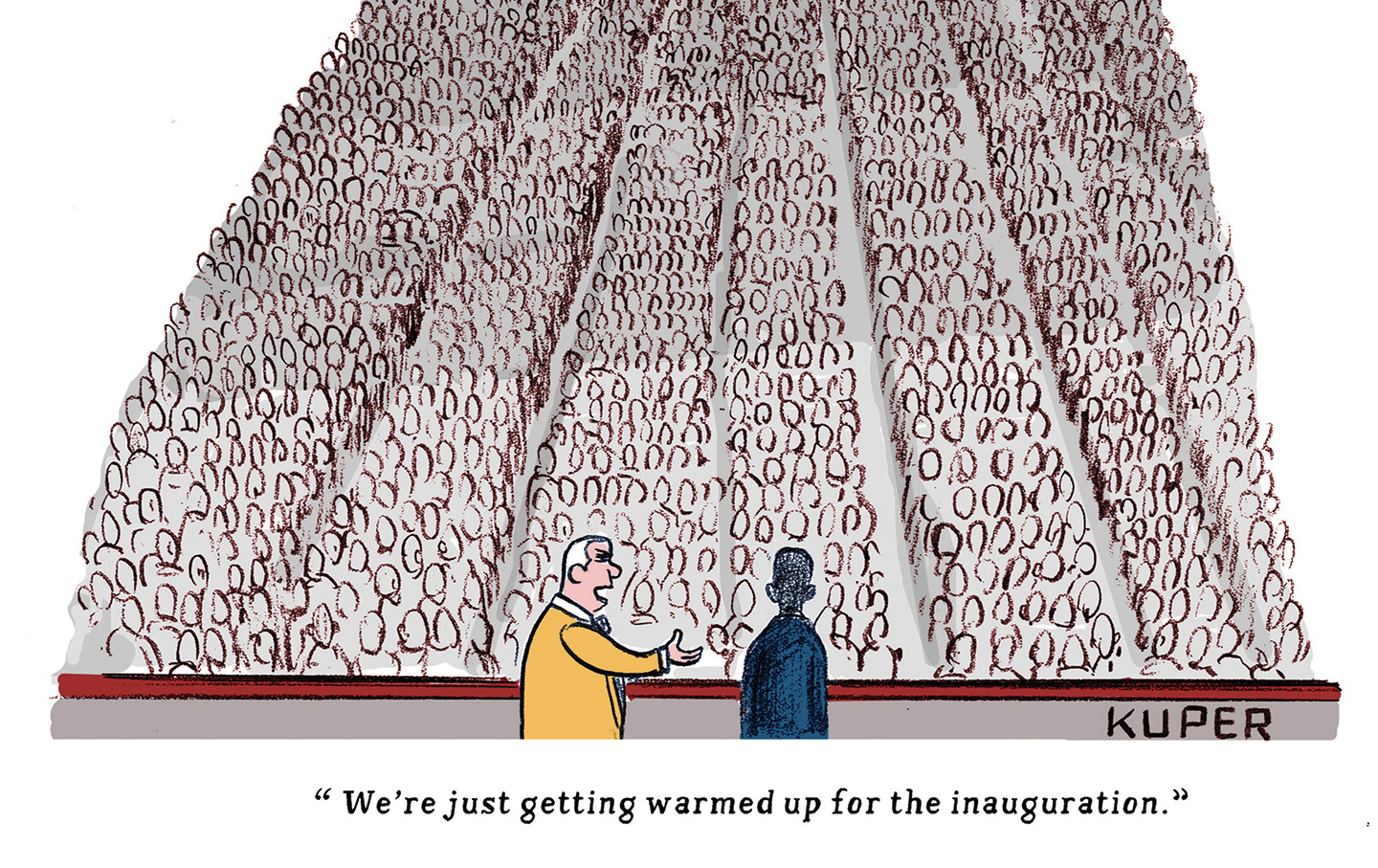

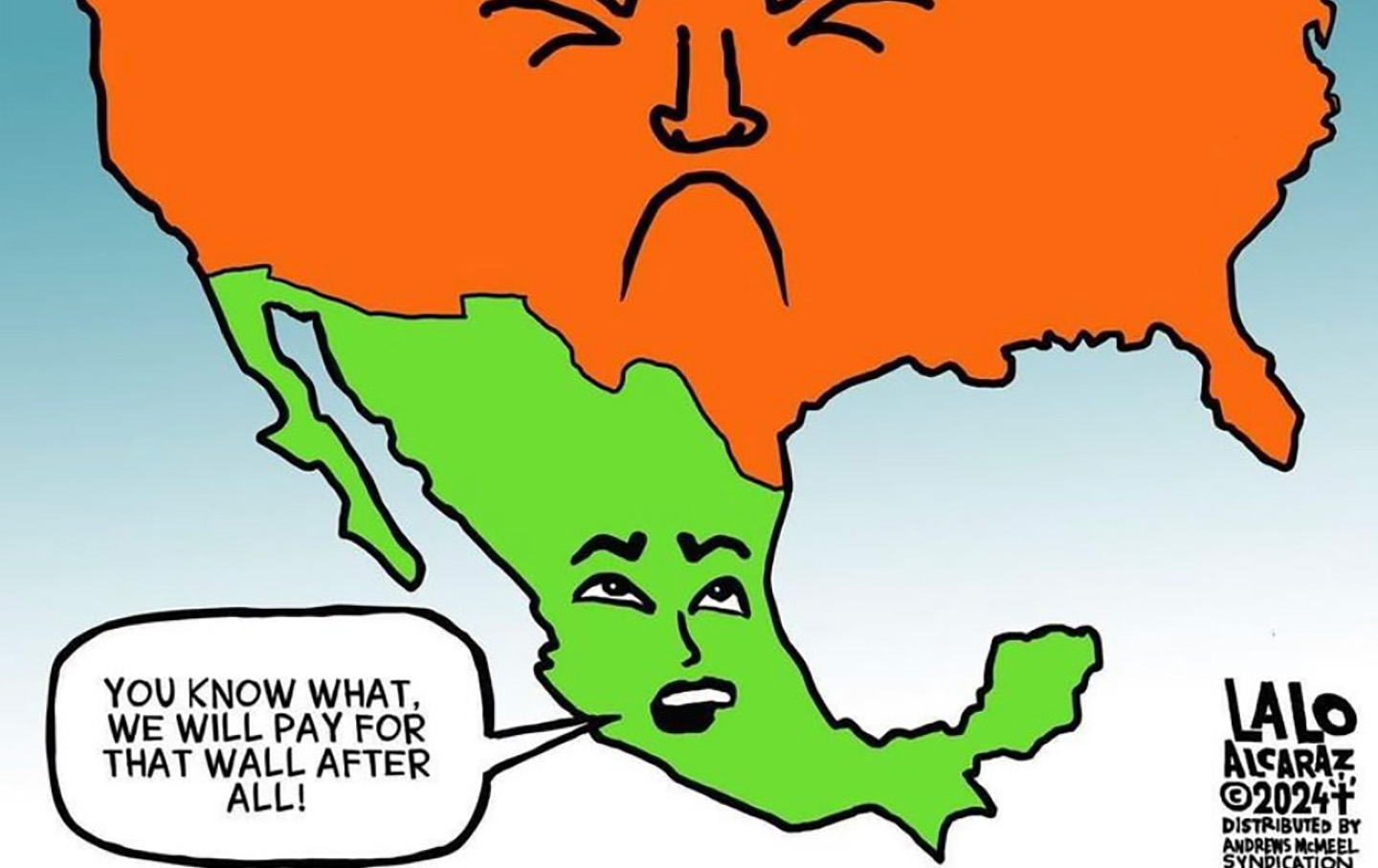

Donald Trump Is the Authentic American Berserk Donald Trump Is the Authentic American Berserk

Far from being an alien interloper, the incoming president draws from homegrown authoritarianism.

If Democrats Want to Reconnect With the Working Class, They Need to Start Listening to Unions If Democrats Want to Reconnect With the Working Class, They Need to Start Listening to Unions

The Democrats blew it with non-union workers in the 2024 election. Unions have a plan to get the party on message.

What Was the Biggest Factor in Kamala Harris’s Defeat? What Was the Biggest Factor in Kamala Harris’s Defeat?

As progressives continue to debate the reasons for Harris's loss—it was the economy! it was the bigotry!—Isabella Weber and Elie Mystal duke out their opposing positions.