The Breakup

What happened to the Democratic majority?

What Happened to the Democratic Majority?

Today the march of class dealignment feels like an inexorable fact of American political life. But is it?

Do political parties make coalitions, or do coalitions make political parties? In American electoral commentary, the commonsense view is that parties stand for certain principles or policies—on gun control, say, or taxes, or abortion—and then ordinary voters line up with the party that is closest to their own beliefs. But for Karl Marx and his acolytes, this view of parties was nonsense. Political parties were defined not by their stated platforms but by the character of their social base. This fact did not need to be reduced to mere “egoistic class interest,” Marx contended in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte; nor did it require a rigid view of social class itself. The party representing the petty bourgeoisie in 19th-century France, for example, was not composed only of “shopkeepers or the enthusiastic champions of shopkeepers.” Its members came from a hundred different places and had a thousand different ideas; they also sincerely believed in the general emancipation of society. Nevertheless, their politics were driven, like water flowing downhill, “to the same problems and solutions” that “the material interest and social position” of their class suggested.

Of course, a narrow and deterministic version of this understanding of parties cannot account for the complexity of real political struggle. Even Marx and Engels, when discussing current events, devoted ample space to many other factors, from philosophy and religion to the quirks of individual leaders. Yet in its broadest historical sense, the Marxist view is difficult to refute. In political warfare, our attention is drawn to the loud artillery blasts of candidates and campaigns, but a party’s ultimate impact generally depends on the much larger, slower infantry movements of its social base.

Consider the history of the oldest mass electoral party in the world today, the Democratic Party of the United States. In the 1820s, it emerged around the magnetic figure of Andrew Jackson, but its political identity was impossible to separate from the coalition that gathered to elect him. This included a range of subgroups, but at its core the party was defined by an alliance between slaveholding elites, urban workers, and small farmers—“the planters of the South and the plain republicans of the North,” in the words of the Democrats’ first great strategic engineer, Martin Van Buren. The party lines may have initially formed around Jackson, but these planters and plain republicans also shared a set of mutual interests, demonstrated by both the issues they fought over (banks, tariffs, and infrastructure) and those that they silently protected from debate (slavery). In a national two-party system, where both sides depended on proslavery support, antislavery politics remained off the table.

This logjam would not be broken from above but from below, when in the 1850s a vast chunk of Northern voters—including many urban workers and small farmers—deserted the Democrats and embraced a new antislavery party. When the Democrats’ social base changed, so too did the party. As a majority of the “plain republicans of the North” became simply Republicans, the Democrats became a regional organization, centered primarily on white voters in the South, with crucial but ancillary support from immigrants in the North. Eighty years later, the Great Depression and the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt transformed the Democratic coalition all over again. In the 1930s, Roosevelt’s commitment to bold economic reform helped win over millions of previously Republican farmers and workers in the North, including most African Americans. The result was a new Democratic Party that could rightly claim to be the first mass party in US history grounded in a clear majority of the working class.

It was no coincidence that after 1933, the working-class Democratic coalition—with the support, and goading, of trade unions—constructed the only rudiments of social democratic government that the United States has ever known, from labor laws and financial regulation to old-age insurance, public healthcare, and support for housing and education. Nor was it a coincidence that this same working-class coalition, spurred by civil rights protests, finally overthrew Jim Crow itself in the 1960s.

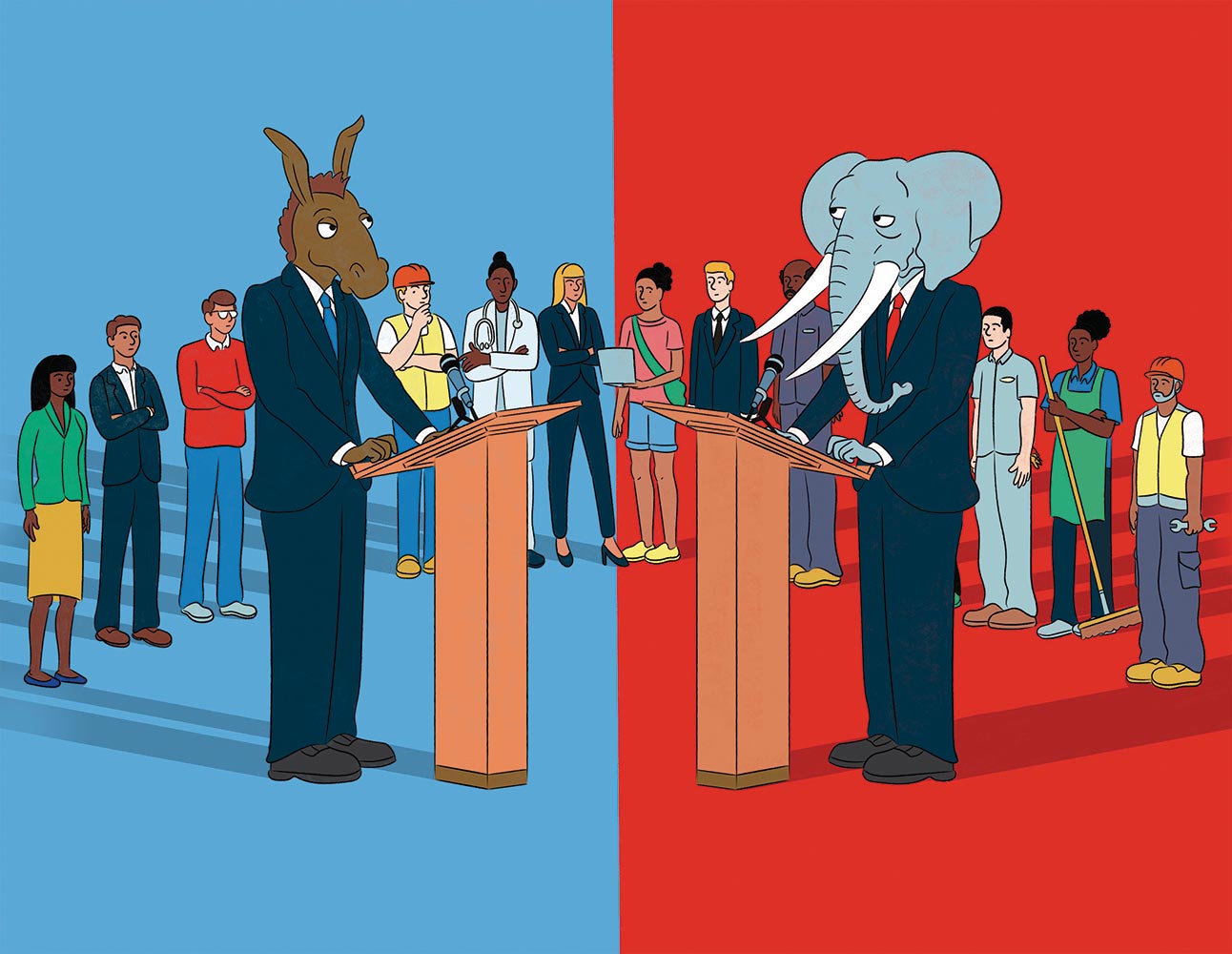

Over the past half-century, the Democratic Party has changed shape yet again. Like other center-left parties around the world, from Norway to New Zealand, the Democrats have lost ground with working-class voters—especially those in blue-collar jobs—while winning more and more support from upper-middle-class professionals. The shift began in earnest in the 1970s, continued across the Clinton and Bush years, and has accelerated rapidly in the last decade.

On the campaign trail and in the White House, Joe Biden has tried to distance himself from this general movement, presenting himself as an old-school Democrat and occasionally attempting to channel the spirit of FDR. Despite the breathless enthusiasm of the liberal press, there are good reasons to doubt whether Biden’s spending program merits analogy to the structural reforms of the 1930s. In any case, an even more dramatic contrast requires attention: The Democratic electorate today looks almost nothing like the coalition that carried the party through the New Deal. In 1944, when Roosevelt presented his famous Economic Bill of Rights, he won about two-thirds of the country’s manual workers. Today, less than 30 percent of manual workers identify as Democrats.

In the near future, the general trend looks likely to continue. A New York Times/Siena College poll last July showed Biden with just 36 percent support from voters without a college degree and 40 percent from voters making under $100,000 a year. Both of these numbers represent historic lows for the Democratic Party. If Biden does manage to fend off Donald Trump in this year’s presidential election, his coalition will almost certainly be anchored by college-educated and higher-earning voters.

Observers of this general phenomenon—the growing cleavage between working-class voters and left-of-center politics—have taken to calling it “class dealignment.” But there is no consensus about its origins or significance. What caused the metamorphosis within the Democratic electorate? Is it possible for the party’s new coalition to win victories or reforms on the scale of the 20th-century party? And if not, then what can the Democrats—or anybody else—do about it?

Few analysts are better positioned to explore these questions of party and coalition than John Judis and Ruy Teixeira. In 2002, they published The Emerging Democratic Majority, which argued that a surging tide of professionals, women, and racial minorities would produce an enduring electoral advantage for the Democrats. During the first, gloomy years of the George W. Bush presidency, that sounded like liberal wishcasting; but less than a decade later, when Barack Obama soared into office with something like the very coalition that Judis and Teixeira had described, the book was hailed as a prophecy.

The celebrations continued apace. In 2009, Teixeira wrote a report for the Center for American Progress that foretold “the decline of the white working class” and “the coming end of the culture wars.” The new Democratic majority, bolstered by the rising millennial generation, would finally terminate social conservatism for good. American political history had reached its apotheosis in the Obama coalition, and progressives had every reason to spike the football in the end zone.

Yet it was not long before history had its revenge. Obama and the Democrats’ shining new majority lasted all of two years before it was unmade by the Tea Party wave of 2010; in statehouses from Wisconsin to North Carolina, Democrats remain buried under the rubble. Over the next decade, Democratic gains with professionals and millennials were negated by the party’s unexpectedly deep losses among the blue-collar working class. Our era has been defined not by an emerging majority of any kind, but by polarization, gridlock, and divided government.

For their part, Judis and Teixeira now regard their 2002 prediction as a failure. In fact, their new book, Where Have All the Democrats Gone?, marks something like a complete reversal in tone, mood, and analysis. Where their last collaboration announced a confident claim on the future, their new book sounds a searching lament for a vanished past.

Where Have All the Democrats Gone? begins in Dundalk, Md., a Baltimore suburb that was once home to the largest steel mill in the world. For most of the 20th century, Judis and Teixeira tell us, Dundalk was reliably Democratic, but as the steel industry declined, its working-class voters drifted to the right: In 2020, Trump won Dundalk with nearly 60 percent of the vote. A former steelworker and ex-Democrat tells the authors that Trump’s victory drew on “a racist element,” but ultimately was “more about class than color…. I think the Democrats are what we used to call the jet-setter class. They are the ones who go to Europe on vacation. They are the ones who don’t care where stuff is made. I think the working class has caught on to that.”

This is surely an exaggeration, but Judis and Teixeira note that it reflects a widely held sentiment—and, indeed, one that now extends well beyond largely white precincts like Dundalk. In the last few years, Democratic support has begun to slip precipitously among less-educated and lower-earning Black, Hispanic, Asian, and other non-white voters. Rather than a revolt of the so-called “white working class,” the Democrats now face a much broader “defection, pure and simple, of working-class voters.”

More from Books & the Arts

To examine how and why, Judis and Teixeira have broken Where Have All the Democrats Gone? into two main parts that assert two distinct arguments, each existing in some tension with the other. The first part is essentially historical and offers a detailed review of national politics since the 1960s, with a special focus on the causes and chronology of class dealignment. Here Judis and Teixeira contend, as forcefully as any member of the Democratic Socialists of America, that “neoliberal” economic policies—under presidents Carter, Clinton, and Obama—bear the lion’s share of blame for the working-class defections from the Democratic Party.

The second part of the book goes in a different direction. It is prescriptive, with the authors offering plainspoken, poll-tested advice to the Democratic Party today. To once again become “the party of the people,” the Democrats must do more than merely return to the liberal economics of the New Deal; they must also break with the “cultural radicalism” that, Judis and Teixeira contend, continues to alienate working-class voters from the party. Now sounding less like leftist tribunes than centrist op-ed columnists, the authors call for a pragmatic “middle ground” on questions of race, gender, climate, and immigration.

This combination of left and centrist politics leaves Judis and Teixeira without a clear ideological address. Whatever one thinks of an alliance between the economic left and the cultural right—“red-brown” portent of fascism, cynical media pose, or useful tactic to promote rail safety in the US Senate—the idea at least produces some frisson. But Judis and Teixeira are not edgy cultural conservatives, just unfashionable moderates. They advocate a suite of positions, from anti-discrimination laws to mixed investment in gas, nuclear, and green energy, that might have passed for liberal common sense in the 1980s but promise to win few disciples today.

This raises a larger problem for Judis and Teixeira: Their historical arguments are too powerful for their prescriptive ones. The very forces that have reshaped the party of Roosevelt into the party of Biden make it almost impossible for the Democrats to embark on the political transformation the authors seek. In this respect, Judis and Teixeira’s studiously “pragmatic” advice may be the most far-fetched element of the book.

The strongest chapters of Where Have All the Democrats Gone? offer an unsparing look at the many ways that the Democratic Party, over the past half-century, has abandoned its working-class base. This is familiar terrain for progressive critics, but the call has a different sound when it comes from inside the house. Judis and Teixeira are, after all, loyal longtime Democrats; as influential journalists, scholars, and consultants, they have devoted much of their life’s work to serving the party in one way or another. This makes their judgment on the party’s leadership more devastating than any indictment from the outside.

The first ripple of class dealignment, the authors argue, came as a backlash to the civil rights legislation of the 1960s. The Democrats can hardly be blamed for the defection of conservative white Southerners who were never more than uneasy partners in New Deal liberalism. But in Judis and Teixeira’s view, the much larger wave of working-class withdrawal came later—not with civil rights but after Democratic leaders began to turn against the New Deal.

The watershed year in this larger shift was 1976, which saw Jimmy Carter win the presidency with strong majority support from working-class voters both Black and white (including white Southerners). But while the first item on the Democratic platform—and a key element of Carter’s campaign—was a plan to achieve full employment, Carter abandoned this agenda once in office and instead attempted to fight inflation with fiscal austerity and business deregulation. The economic consequences were bad, but Judis and Teixeira insist that the political upshot was even worse: After “the Carter debacle,” the Democrats “would never fully recover their reputation as protectors of the average American.” The defeat of New Deal economics was also the beginning of the end for the New Deal coalition.

After Ronald Reagan won office in a landslide (twice), the Democrats’ situation went from bad to worse. Hoping to break the Republican stranglehold on the White House, party leaders tacked farther to the right, hoping to “promote the Democrats as a party of business and free markets.” The ideological shift went hand in hand, as historians like Lily Geismer have shown, with the electoral courtship of moderate suburban professionals. The so-called New Democrats succeeded in electing Bill Clinton in 1992, but for Judis and Teixeira, even this victory was a poisoned chalice. The party’s full-bodied embrace of neoliberal policy—balanced budgets, aggressive deregulation, and ambitious free trade deals—ultimately cost the United States 3.4 million jobs, many of them in blue-collar industries. Economically, Clinton’s reign accelerated the triumph of finance over manufacturing; politically, it cemented the Democrats as a party whose links to Wall Street, Silicon Valley, and upscale professionals counted more than its older alliances with labor unions or working-class voters.

The avatar of the emerging Democratic majority, finally, comes in for some of the strongest criticism of all. Like Franklin Roosevelt before him, Barack Obama took office with a landslide mandate to reform an economy in crisis. But that historic opportunity was squandered. In the White House, Judis and Teixeira argue, Obama governed as “the last New Democrat,” seeking “a third way…between New Deal liberalism and Reagan conservatism, solicitous of the poor and unemployed, but also of business confidence and the danger of deficit spending even during a recession.” Obama’s inadequate stimulus bill did not halt job losses; his healthcare reform, while expanding coverage through Medicaid, failed to bring down runaway costs for the vast majority of Americans. Meanwhile, he consented to entitlement cuts, pursued free trade deals, and did little to check Wall Street or support labor. During the Obama administration, union membership kept falling while inequality remained at a record high.

Despite their business-friendly records, Judis and Teixeira point out, Clinton and Obama both campaigned as populists of a sort, adopting the traditional Democratic portrayal of Republicans as bloodless, distant plutocrats. It helped, of course, that their Republican opponents often fit this description. Obama’s “populist moment” in 2012, when he ran against private equity CEO Mitt Romney, helped him secure just enough working-class votes to win reelection.

Nevertheless, the steady trickle of class dealignment continued, especially in downballot races—and in 2016, it became a deluge. Seeking to mobilize the Democrats’ new professional-class coalition against Donald Trump, Hillary Clinton ditched even the rhetorical trappings of economic populism. The strategy paid off in wealthy suburban strongholds like Fairfax County, Va., but it helped Trump to rampage across the industrial Midwest and into the White House.

Today, the march of class dealignment feels like an inexorable fact of American political life. Joe Biden may not have restarted the New Deal, but between his spending bills, tough trade policy, and support for labor, he has at least broken with the neoliberal dogma that ensnared Carter’s, Clinton’s, and Obama’s presidencies. Yet so far, it appears to have made little difference with working-class voters, who seem less inclined to support the Democrats in 2024 than they did in 2020.

Judis and Teixeira think they know why. As organized labor’s strength has declined, its influence within the Democratic coalition, they argue, has been replaced by progressive think tanks, foundations, media outlets, activist groups, donors, and academics. These institutions, which function as what the authors call a “shadow party,” largely reflect the liberal and left-wing values of “young professionals in the large postindustrial metro centers and college towns.” Meanwhile, the larger Democratic coalition has come to include vital support from wealthier voters in culturally aligned industries, including the dynamic sectors of finance and technology. As a result, the Democrats have swung to the left on questions of race, gender, immigration, and climate. This newfound radicalism, along with what Judis and Teixeira call a more general “cultural insularity and arrogance,” has driven away working-class voters with more moderate views.

To regain these voters, Judis and Teixeira conclude, Democrats must trim their sails on these subjects and reclaim a middle ground. In the authors’ view, this does not mean altering the party’s basic commitments to civil rights, lawful immigration, and action to combat climate change. But it does involve a retreat from positions that, polls suggest, have put the party at odds with a majority of voters, such as supporting trans athletes in women’s sports or opposing the use of natural gas. It would also mean adopting a more cautious, moderate vocabulary on these and related questions. Rather than heighten the tensions in an unwinnable war of values, Democrats should seek to lower the temperature with bland affirmations of patriotism, simple opposition to prejudice, and a general openness to disagreement.

The argument here is worth unpacking. In historical terms, it is hard to dispute Judis and Teixeira’s evidence: Over the past decade, certainly, the Democratic Party has moved left on questions of social policy. The most obvious, oft-cited example is same-sex marriage, which Hillary Clinton opposed as recently as 2013 yet has now become such an article of faith within the party that it no longer even rates discussion. But on other policies that Judis and Teixeira cite—from gender-affirming care to carbon emissions targets—the Democratic baseline is significantly more progressive and ambitious today than it was in the Obama era, never mind a generation ago. Open a newspaper from the 1990s and you’ll find the Republicans making highly familiar arguments about abortion, crime, and border security. You’ll also find the Democrats—in the party’s 1996 platform, for example—celebrating a drop in the abortion rate, touting “the toughest crime bill in history,” and vowing to crack down on “illegal immigration.” For all the talk of a Republican turn to the right in the age of Trump, on most issues the 21st-century Democratic shift to the left has been far more dramatic.

Yet this very real historical shift is one major reason why the Democrats are so unlikely to take Judis and Teixeira’s advice. For crucial Democratic constituencies—the “shadow party,” but also a broader voting coalition—these are the very issues that drive political commitment in the first place. Nor is it clear that the party’s leftward shift has exacted such a terrible price at the polls. Indeed, the Democrats have junked Clinton-era social conservatism, written progressive policy into law in states from Oregon to Minnesota, doubled down on their alliance with progressive elites in the media, the entertainment industry, and academia, and still managed to remain competitive as a national party.

It is in the nature of progressive politics to discount the victories it has already achieved while exaggerating the power of reaction and backlash. But on the whole, the past few decades raise the possibility that the battle of values may be winnable after all. Even concrete right-wing victories, like the Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs, have only affirmed the weakness of 1990s-style cultural conservatism in national politics: Its appeal is so limited that even Trump has abandoned it. Judis and Teixeira can brandish all the polls and surveys they like, but they are proposing a cease-fire to an army that has swept the field: Why should Democrats abandon the culture war when it has yielded them so much fruit?

The Democratic coalition today is built to fight, and perhaps to win, this struggle. It is not built to become a “party of the people,” a vehicle to oppose elite rule, or a force for major economic reform. Insofar as the upper-middle-class Democratic base finds itself pinched or bruised by the reckless march of capital, it may consider mild adjustments to the fiscal or regulatory order; insofar as it wishes to reward the less-advantaged voters inside the coalition, it may support mild increases in welfare spending. But a party that wins 60 percent support from the wealthiest 10 percent of the country and 75 percent support from top earners in business and finance and that claims enthusiastic allegiance from much of the billionaire class will not organize a new New Deal. Its “material interest and social position” simply does not favor a transformation of class power in the United States—or, to say the same thing in different words, a government that can deliver good jobs, healthcare, housing, and education to all its people. To change the world, the Democrats will first have to change themselves.

More from The Nation

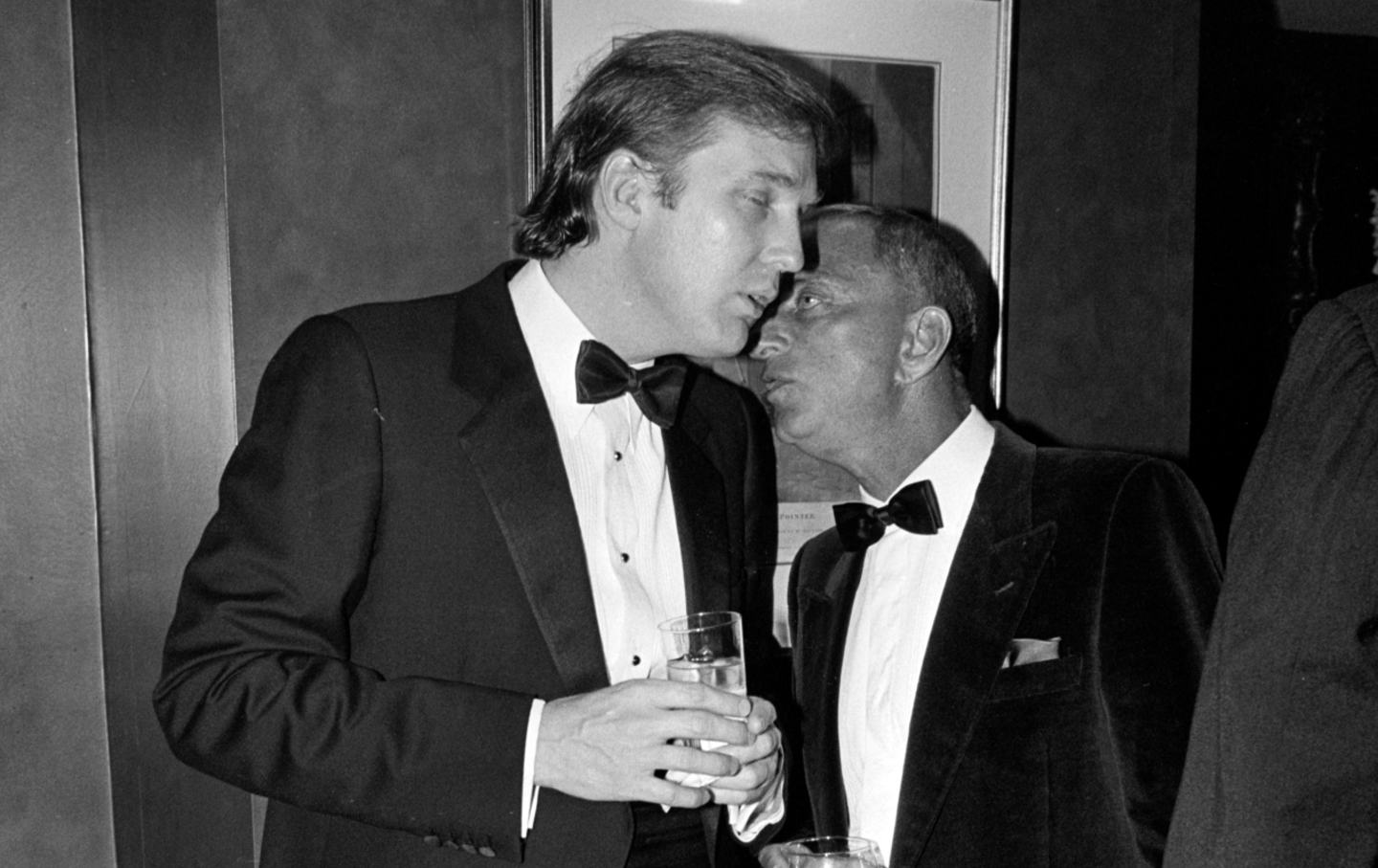

Donald Trump Is the Authentic American Berserk Donald Trump Is the Authentic American Berserk

Far from being an alien interloper, the incoming president draws from homegrown authoritarianism.

If Democrats Want to Reconnect With the Working Class, They Need to Start Listening to Unions If Democrats Want to Reconnect With the Working Class, They Need to Start Listening to Unions

The Democrats blew it with non-union workers in the 2024 election. Unions have a plan to get the party on message.

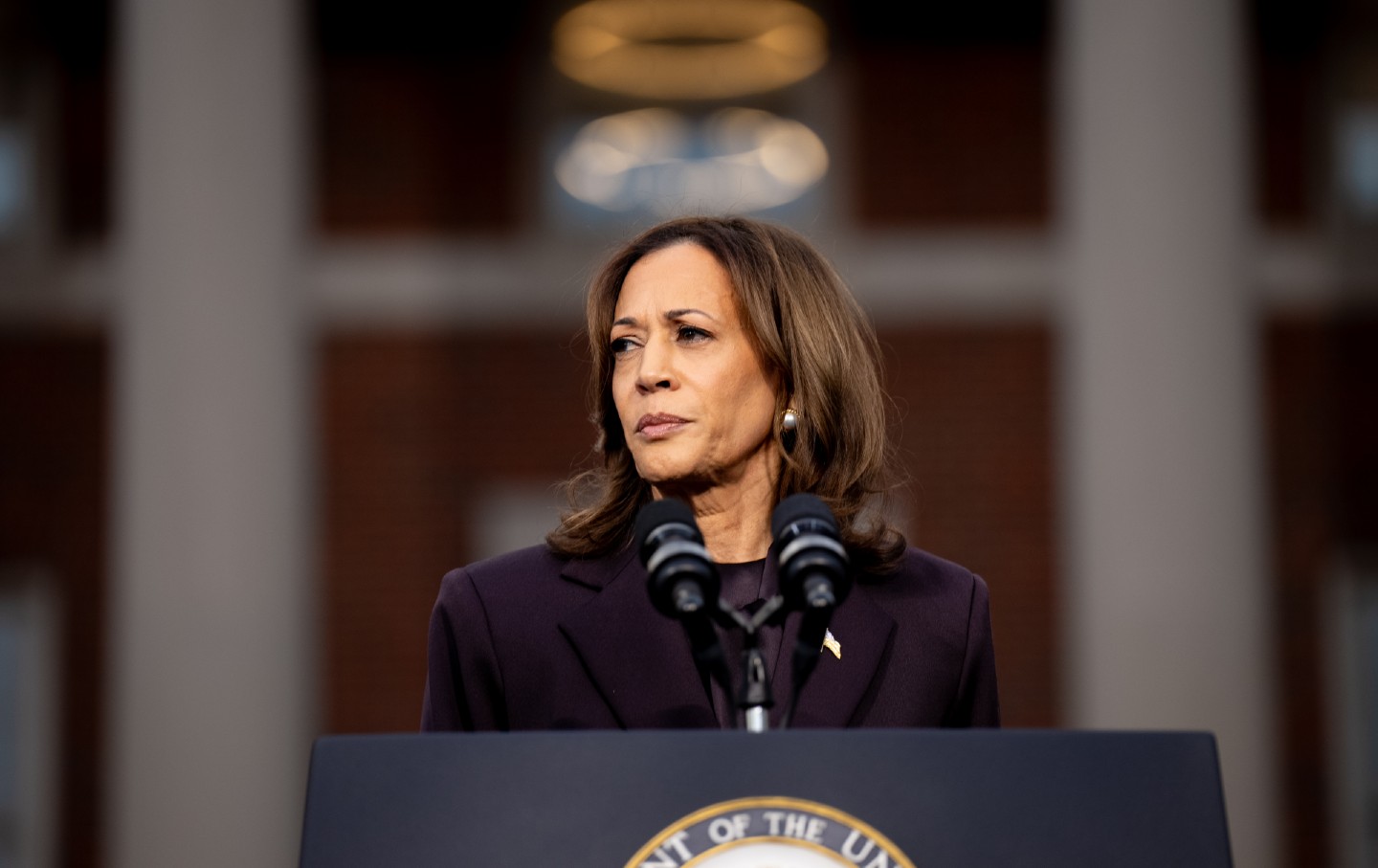

What Was the Biggest Factor in Kamala Harris’s Defeat? What Was the Biggest Factor in Kamala Harris’s Defeat?

As progressives continue to debate the reasons for Harris's loss—it was the economy! it was the bigotry!—Isabella Weber and Elie Mystal duke out their opposing positions.