The Metaphysical Horror of “The Curse”

From its first moments to its antic end, the series exposes its viewers to an abundance of anxious perturbation but it does something else too: It reveals the absurdity all around us.

Liam Eisenberg

About halfway through the 10th and final episode of Showtime’s The Curse, the laws of physics spontaneously change. Without warning or explanation, Asher (Nathan Fielder) is sucked up off the ground by a sudden force apparently trying to eject him from the earth’s atmosphere; simultaneously, his wife Whitney (Emma Stone) goes into labor. The last half-hour cuts between confused firefighters trying to coax a terrified Asher to let go of the tree branch he’s clinging to for dear life—they’ve done this before, they assure him, for “tons of bears”—and surprisingly graphic scenes from Whitney’s C-section delivery. Before this point, The Curse hewed closely to reality—often too close for comfort. The series followed Asher and Whitney Siegel, would-be reality stars on the HGTV network, in their efforts to transform a small New Mexico city into a gentrified eco-haven. The series’ dramatic and unexplained slip from the couple’s believably absurd real estate ambitions into all-out fantasy is surely one of the most chaotic moments in television history, right up there with Josie Packard’s transformation into a drawer knob in the final episode of the original Twin Peaks.

In a way, it comes as a bizarre relief, a cathartic release to a season-long buildup of tension—between Asher and Whitney and the people whose lives they disrupt, but also between the show and its audience. For most of the series, the impulse to laugh is usually paired with a squeamish, amorphous feeling of guilt and complicity (at what and with whom, we’re often not sure), and these last wild scenes offer us a merciful escape from this disquieting experience—a moment of true, unadorned absurdity. One can’t help but laugh—more out of hysteria than hilarity—at Fielder’s and Stone’s feats of physical tragicomedy, with a pregnant and panicking Whitney dragging herself on the floor between pieces of furniture, and Asher attempting hideous acrobatics on the ceiling as he attempts to stay calm and comfort his wife.

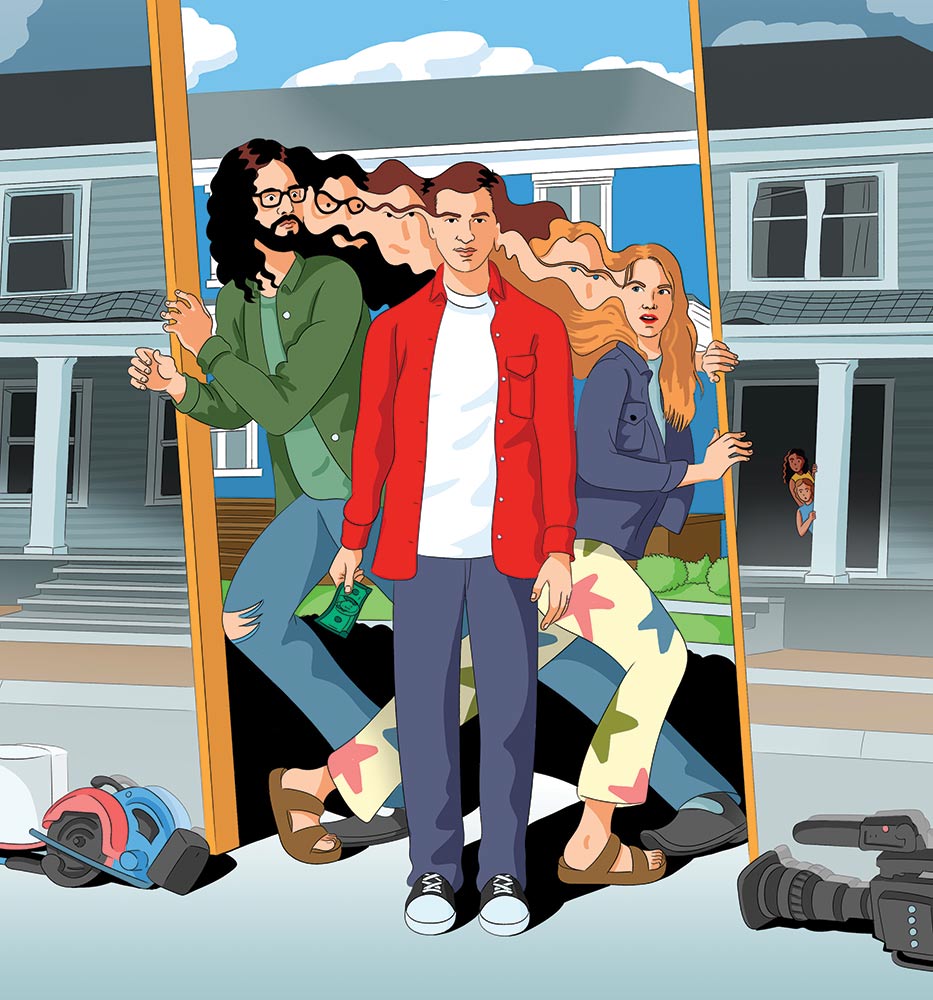

The Curse is the brainchild of Fielder and Benny and Josh Safdie—an unholy trinity of our greatest auteurs of discomfort. From its first moments to its antic end, the series exposes its viewers to an abundance of anxious perturbation. Though stylistically not the most obvious match, Fielder and the Safdie brothers share an interest in taking their audiences to the edge of what is comfortable and then deserting them there—whether through the how-far-can-he-go experiments of Fielder or the how-bad-can-it-get anxiety bombs of the Safdies. Fielder’s comedy of social transgression—often insufficiently referred to as “cringe”—and the Safdies’ brand of harsh, fluorescent-lit realism can at times seem as though they don’t have much in common, but both revel in the monstrosity found in everyday life—the ways in which the quotidian can unexpectedly branch off into hell.

The premise of The Curse follows one such branch, starting on mundane terrain before forking off into derangement. It initially looks like a prank from Fielder’s first show, Nathan for You, on a cruelly inflated scale: Whitney and Asher Siegel are a newlywed couple hoping to start a “passive home revolution” in their adopted town of Española, N.M. They plan to do so by peddling mirror-walled $850,000 eco-homes in a city with a median household income of $44,427. Of course, they aren’t motivated by half-baked altruism alone: They also seek to publicize both their moral imperatives and their development company, and so they enlist Dougie (Benny Safdie), a demonic but tortured reality show creator—and Asher’s childhood bully—to develop an HGTV show charting their course as they attempt to transform Española, make millions, and save the world “one kilowatt at a time.”

Much of the series’ initial awkwardness stems from Whitney and Asher’s seemingly earnest and wholehearted belief in their mission. It’s immediately clear that their scheme is ultimately just an effort to profit from their rebranding of gentrification. Yet they unblinkingly insist throughout the early episodes that “while affordability may be decreasing, opportunities are rising” in Española due to their efforts—such as bringing a high-end Australian coffee shop and an expensive designer-jeans store that no resident can afford to join their “Española Passive Living” office in the town’s otherwise deserted strip mall.

But what begins as mere cringe grows quickly into a full-body shudder. Whitney and Asher, white saviors narcissistically fixated on not coming off like white saviors, at first serve as easy targets for a series of running gags (including one about micropenises). However, things get weirder as the show progresses. The straightforward send-up of privileged millennial liberals who want to be viewed as unimpeachably good while reaping vast profits off an existing community begins to spread into a more pervasive critique of contemporary life. As we see the unfolding consequences of the Siegels’ attempted development of Española, we get insight into not only into the unhinged dynamics of their marriage and Dougie’s psychological torments but also the moral compromises, small and large, that nearly everyone we encounter ends up adopting. As the world of the show grows steadily darker, The Curse takes on the horror-movie connotations of its title.

The show’s formal elements mimic this worsening sense of foreboding. The couple’s suburban mirrored houses—which are fun-house knockoffs of Doug Aitken installations, though Whitney denies the obvious connection—seem merely an audacious visual gag at first, much like the unveiling of the full-scale replicas in Fielder’s The Rehearsal. But the houses grow increasingly menacing as the season proceeds; faces and figures are frequently shown as warped, ghastly reflections in their exteriors. The show’s score, by the Safdies’ frequent collaborator Daniel Lopatin (better known as Oneohtrix Point Never) and John Medeski (of Medeski Martin & Wood), follows this lead. The droning synths slide queasily off-key from moment to moment, a sonic equivalent to the twisted images reflected in those mirrored façades. The suggestion of the supernatural always lurks on the periphery, as Asher becomes convinced that “the curse” of the show’s title is real, cast on him by a young Black girl named Nala (Hikmah Warsame), whose intermittent scenes at school and at home, with and without the Siegels, offer the viewer much-needed moments of earnest emotional attachment.

Yet even as The Curse slips increasingly into the uncanny, the show’s true horror, as in Fielder’s and the Safdies’ previous work, lies in its commitment to depicting reality. The atmospheric cues of the horror movie may predominate, but it’s actually the strains of realism that offer the most scares: the weaponized awkwardness of the Fielder documentary, the cinema verité hints of Good Time and Uncut Gems, the immaculate pastiche of an HGTV reality show. The Curse’s main characters are made more and more monstrous by dint of their humanity, not in spite of it. The moments that make us most sympathetic to Whitney, Asher, and even Dougie also make us recoil that much more from them—such as the subplot about Dougie’s responsibility for his wife’s death, or the intense loneliness and insecurity behind Whitney’s need to be liked by the very people she’s taking advantage of (Stone’s expressions constantly ripple and warp with incredible subtlety and speed, as though reflected in one of Whitney’s houses). Supernatural forces aren’t needed to make the world of the show a brilliant, horrifically believable hellscape. Asher himself acknowledges as much in the penultimate episode. Tearily admitting that, if anything, his presence is the real blight on the town, he says, “I am the problem—it’s not magic, I’m a bad person.”

How, then, should we understand the last episode’s anti-gravitational leap into The Twilight Zone, if its satire is so firmly rooted in the real world? We don’t need magic, after all, to see the bad and the good of the characters or even the bad and the good in ourselves. The final episode’s unexpected genre shift does, however, keep all of the answers to the show’s central mystery available: Who or what really is “the curse”? There’s Asher’s own admission that he is—but this change in the rules of reality reopens the possibility that Nala’s “tiny curse” (inspired not by malice but by a TikTok trend) may have unintentionally worked, or that Dougie, who mutters “I curse you” behind Asher’s back with vitriol in a late episode, has more power than he realizes. All bets are off once gravity stops working. Then there’s the notion that Whitney herself may be the curse. In the 1961 Twilight Zone episode “It’s a Good Life,” the inhabitants of a small town live in fear of “the monster,” a 6-year-old “with a cute little-boy face and blue, guileless eyes” named Anthony, who is capable of banishing people “to the cornfield,” a mysterious void from which they never return—just as Asher is consigned to the cosmic cornfield once Whitney’s child is born. It’s surely no coincidence that the episode in which we begin to understand how Whitney’s ill-gotten generational wealth, millennial smugness, and white privilege have made her a “monster” is called “It’s a Good Day.”

Or perhaps the curse is our culture of cruel spectacle itself, an idea suggested by the show’s beginning and end. “Oh, so it’s for TV?” an onlooker asks mildly, untroubled by Asher’s violent end, echoing Whitney’s gloss on the exploitative first scene of the series: “It’s a little TV magic for you.” The curse, it turns out, is not just Whitney, Asher, or Dougie but all of the conditions that create them—and we’re surrounded by them too. “It’s a Good Life” ends with Rod Serling’s customary warning: Should you one day run into a boy like Anthony, you can be sure that you’ve entered the Twilight Zone. But The Curse, despite its fantastical ending, leaves us with a far more unsettling realization: The terrors of the show are not siloed off from real life. We encounter versions of Whitney and Asher and Dougie every day, and when we do, it isn’t because we’ve just entered the Twilight Zone—it’s because we’ve always been there.