The 1968 Democratic National Convention, Then and Now

The Nation warned readers early on that the 1968 convention would be a debacle.

With the Democratic National Convention wrapping up in Chicago, many have pointed to parallels with the party’s convention in the same city back in 1968, when an aging, uninspiring incumbent president bowed out of his re-election bid and protesters took to thes treets to call for an end to a horrifying and unjust war. But as historian Rick Perlstein has pointed out, the differences between then and now are at least as significant as the similarities.

Readers of The Nation got an early warning that the upcoming convention was likely to turn into a debacle—if not an outright disaster. In May 1968, three months before Democratic delegates descended on Chicago for the party’s national convention, The Nation ran a feature story with the headline “Battle of Chicago: A Study in Law and Order.”

It had, of course, already been an eventful year in Democratic politics. Back in March, the incumbent president, Lyndon B. Johnson, bowed to a brewing intraparty rebellion and ended his bid for reelection. Vice President Hubert Humphrey quickly replaced him as the establishment favorite. The Nation celebrated Johnson’s move as long overdue and urged readers to consolidate support behind Johnson’s anti–Vietnam War challenger, Senator Eugene McCarthy. Even after Robert F. Kennedy entered the race as another anti-war candidate, the magazine reiterated its opinion “that all those who oppose the war and want to see a redirection of American power and a reordering of national priorities should continue to support Senator McCarthy…. Both in style and substance, Senator McCarthy has shown a real awareness of the need for a new politics.” But the magazine admired the youthful energy that Kennedy’s candidacy had brought to the political scene. In late May, the editors even suggested tossing a coin at the Chicago convention to see whether McCarthy or Kennedy would top the Democratic ticket, while the other could serve as running-mate.

That idea was extinguished a week later, when Kennedy was shot dead at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles following his victory in the California primary. Coming just two months after Martin Luther King’s death and five years after John F. Kennedy’s, RFK’s assassination was “the most senseless killing of them all,” The Nation posited, “a tragedy that goes deeper than the bullet.” After all, RFK’s campaign had been based on ending the war in Southeast Asia that his brother’s administration had started. It revolved around an appealing narrative of redemption, and not only for the country:

It was [John] Kennedy who, in one way or another, gave Johnson the opportunity to involve the United States in a great war on the mainland of Asia and thus by necessity to ignore all the problems, domestic and foreign, that today beset the most powerful of nations. And it was this whole mindless, cruel drift that Robert Kennedy was determined to stop. He was moved by impulses of the most responsible patriotism but he was also moved by family: the Kennedys are proud. He would secure his brother’s good name by defying, and if possible defeating, the evil consequences that had flowed from his brother’s brutally interrupted administration. And now a bullet has put a stop to that.

It wasn’t enough to mourn Kennedy’s death with words; a fitter tribute would come in the form of action—coalescing around McCarthy’s campaign against both Humphrey and likely Republican nominee Richard Nixon, “those spokesmen for the discredited machinery of political consensus that RFK was determined to break.”

In late April, just weeks after riots consumed Chicago—like other American cities—following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., Mayor Richard Daley orchestrated a concerted municipal effort to shut down a legally permitted annual peace parade. This effort, “a planned series of provocations,” as the Chicago journalist Joseph L. Sander wrote in The Nation, “produced the anticipated result of blood on the civic center pavement” and foreshadowed the approach Daley was likely to take when the Democratic National Convention met three months later. Daley’s administration appeared to be “trying to get across the message that it will not tolerate peaceful demonstrations by local citizens and that any who try to make their grievances known to the public will be made to wish they hadn’t,” Sander reported.

In August, altogether predictably, mayhem broke loose outside the convention hall as cops assaulted both journalists and peaceful protesters. “The Chicago police are a special breed,” Nation editor Carey McWilliams wrote in the next issue. “My guess would be that they weigh on average about 50 or 60 pounds more than the average for New York’s finest. Even before the trouble started, it was clear that they were spoiling for a fight, and not merely with yippies and hippies. They were uptight, period…. The effect of this awesome demonstration of military and police muscle was to create an atmosphere so hateful and oppressive that it drew a mild protest even from joyous Hubert [Humphrey, who clinched the nomination at the convention].”

McWilliams continued: “An enormous audience in this country and abroad watched the disgraceful Chicago street scenes. If Daley had wanted to get the Democrats off to a bad start in this year’s convention, he could not have done any better than he did.” The spectacle was “grotesque, surreal and reminiscent of Storm-trooper tactics in Germany of the 1930s.”

Despite the gruesome “pacification” campaign by Daley’s troopers, McWilliams saw some cause for hope in the 1968 Chicago convention. McCarthy’s and Kennedy’s campaigns had brought young people into politics. Black-led delegations from Southern states for the first time replaced segregationist Dixiecrats. And there were already signs that the age-old convention process itself—which gave the power for picking presidential candidates to Daley-like machine politicians and backroom operators—would be reformed to give more voice to ordinary voters:

Despite the rigging, wire pulling and other Daley tactics—with the big man signaling his wishes to various chairmen on the floor—and despite the size of the Humphrey vote, one sensed the existence just beneath the surface of a strong political insurgence which could not break through, in part because it did not quite know how and also because the old hands were still operating the controls. In 1972 it could be a different story. Because this potential exists it is a national misfortune that the party did not repudiate Johnson, as the people had done [in state primary elections that went for McCarthy and Kennedy]. The party is now stuck, if not with him then at least with his legacy: a gravely weakened party structure, the possibility of a walkout of those elements most needed to reorganize and revivify the party, and the awesome burden of defending the Johnson-Humphrey record on Vietnam. By failing to repudiate the Johnson legacy, the Democrats have not only improved Richard Nixon’s chances of winning in November, they have also gravely hobbled Democratic nominees in every state.

Indeed, come November, Nixon won in a near-landslide—301 Electoral College votes to Humphrey’s 191 (George Wallace, the segregationist Alabama governor, gained 46, all in the former Confederacy). While many commentators interpreted the victory as a “swing to the Right,” The Nation dissented from that view, noting that “it is unreasonable to assume a swing to the Right, in an election in which there was no Left.” Rather than the serious anti-war alternative of McCarthy, the public had been given a “choice of candidates all of whom were essentially conservative in terms of today’s needs and problems.”

The election of Nixon was an unmitigated disaster. “Something about this strange man conveys an impression of almost total insincerity and bottomless personal insecurity,” The Nation reflected in a November editorial. But at least the thorough trouncing of the Johnson-Humphrey establishment suggested there might be some hope for a revitalization of the Democratic Party: “Of course a harsh struggle will take place for party control, but on balance circumstances favor the ultimate success of those who are out to refashion the Democratic Party. The old coalitions are breaking up, new coalitions and alignments are re-forming, and above all, new issues are emerging.”

As Rick Perlstein noted in an interview with Vox, despite the superficial resemblances between 1968 and 2024, one reason it’s unlikely the shocking events that took place back then could happen again today is precisely because of reforms passed after the 1968 debacle—the reforms The Nation celebrated in its post-election editorial—which brought long-excluded constituencies like Black people and women into the Democratic Party in unprecedented ways. “History is a process, it’s not parallels,” Perlstein said. “We can’t have 1968 again because we already had 1968.”

The only question now is what future we will have because we had 2024.

More from The Nation

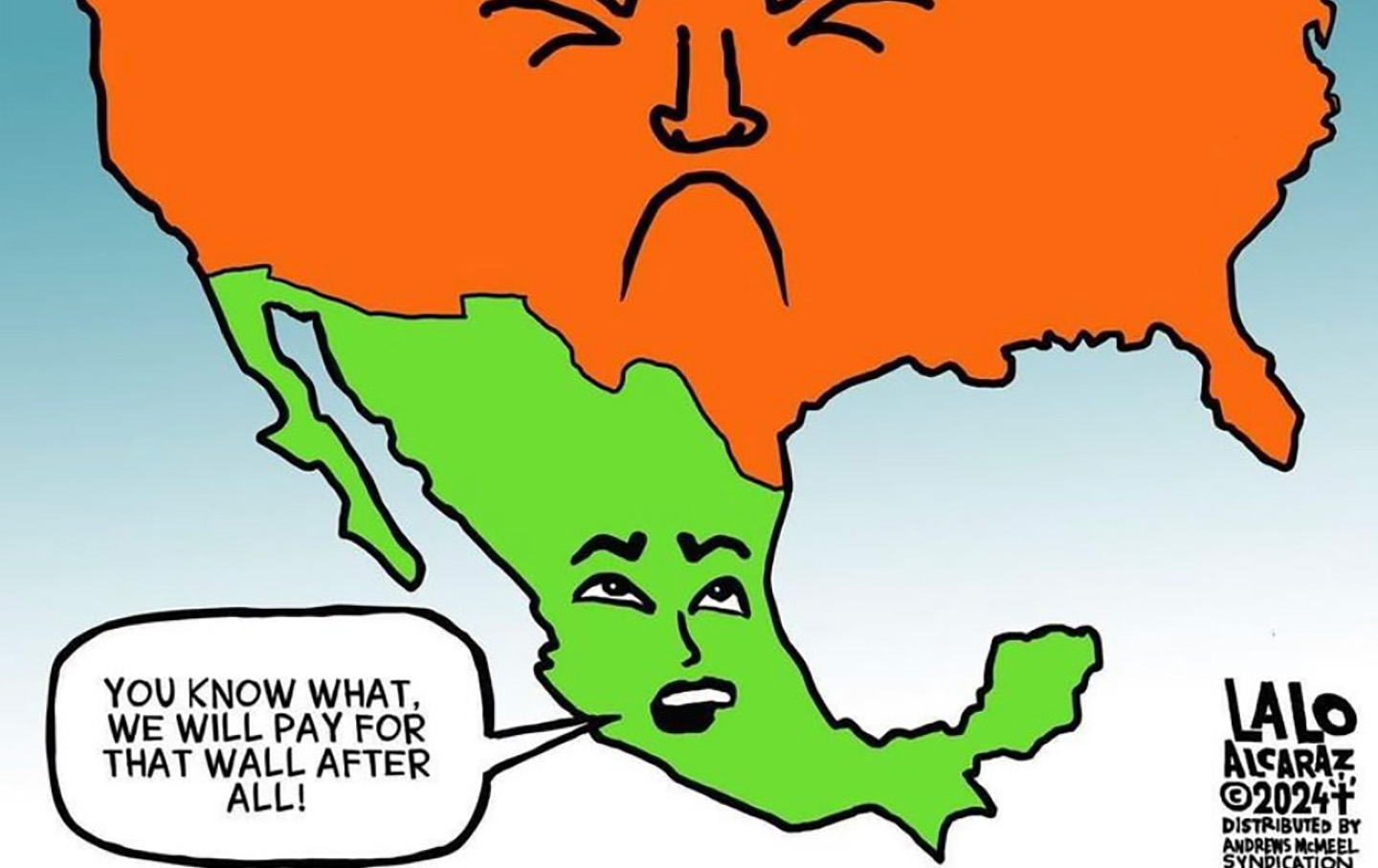

Donald Trump Is the Authentic American Berserk Donald Trump Is the Authentic American Berserk

Far from being an alien interloper, the incoming president draws from homegrown authoritarianism.

If Democrats Want to Reconnect With the Working Class, They Need to Start Listening to Unions If Democrats Want to Reconnect With the Working Class, They Need to Start Listening to Unions

The Democrats blew it with non-union workers in the 2024 election. Unions have a plan to get the party on message.

What Was the Biggest Factor in Kamala Harris’s Defeat? What Was the Biggest Factor in Kamala Harris’s Defeat?

As progressives continue to debate the reasons for Harris's loss—it was the economy! it was the bigotry!—Isabella Weber and Elie Mystal duke out their opposing positions.