Siddhartha Deb and the Politics of Fiction

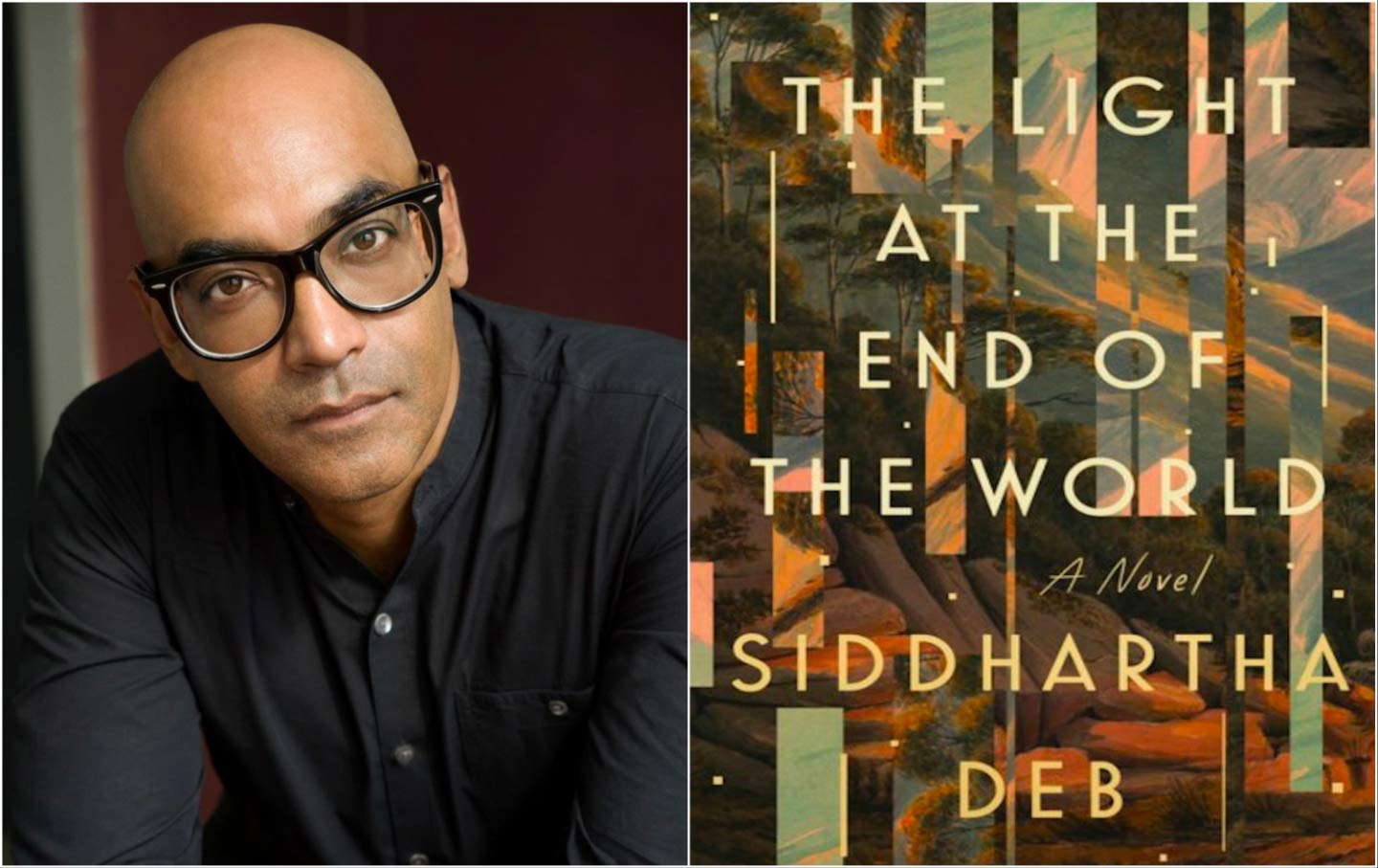

A conversation with the novelist and journalist about India, colonialism, the Union Carbide catastrophe, solidarity, history in literature, and his novel, The Light at the End of the World.

Siddhartha Deb is an accomplished novelist and journalist. He is the author of two previous novels, The Point of Return and An Outline of the Republic, and The Beautiful and the Damned, a work of narrative journalism about the inequities deepened and reinforced by the economic transformation in globalizing India, and one subject to an ongoing lawsuit in India. Now in his new novel, The Light at the End of the World, he tells a series of sometimes interlocking and sometimes bifurcating stories about India—each about a defining moment in the nation’s history: “City of Brume” evokes New Delhi’s dystopic near future; “Claustropolis: 1984” captures the internal drama of a bigoted hitman around the Union Carbide catastrophe in Bhopal; “Paranoir: 1947,” unfolding in a restive Calcutta in the year of Indian independence, follows a veterinary student spooked by the prospect of piloting an ancient Vedic aircraft; and in the fourth and final novella, “The Line of Faith: 1859,” the British colonizers’ desire to chase a mutineer turns hilarious and absurd with their own their lives and sanity threatened. With its liminal characters and phantasmagoric specters, The Light at the End of the World constantly moves between the realms of the technological and the human, the past wounded by colonialism and the bleak biomes of the future. It is an enraged epic but also one full of humanity; its various epochs of bigotry, intolerance, and hate are interspersed with tender moments of solidarity, love, and compassion.

—Feroz Rather

Feroz Rather: Through your novel, you destabilize linear, seamless ways of looking at India’s modern history that’ve been consolidated over the years through the overarching lenses of progress, independence, and nationalism. How do you conceive of history and in particular how do you write about it in your novels?

Siddhartha Deb: History is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake. That’s one part of it, absolutely, in the way it has shaped my early novels and their exploration of borders, forced migration, colonialism, and ethnic conflict, and in the way it leads to interruptions and ruptures in the narrative arc. That notion of history provides a driving impetus to this novel and its end-of-world moments—colonialism, the Partition, the Union Carbide disaster, and the slow-motion, fascism-fueled wreckage that is India’s present and near future. But in something of a departure from my earlier works, which worked mostly within the boundaries of realism, history is also a possibility in this novel—a zone of the counterfactual, the speculative, and the transgressive. History is not just oppressive but also sufficiently weird to be potentially liberating. History, when filtered through narrative, can take unexpected, unpredictable turns in genre as well as form and in this way offers a release, even the possibility of light.

FR: Speaking of form and genre, The Light at the End of the World is so radically different from your previous novels, The Point of Return and An Outline of the Republic. The narrative is full of discontinuities, phantasmagoric and purposely disorienting. What led you to break from more traditional boundaries of realism?

SD: I’m happy to hear that you found it radically different from the earlier novels. To add to what I said above, I’d begun to find realism in fiction deeply intertwined with liberalism in politics. Some of this has to do with how realism has become embedded into professional structures of publishing, which are global, corporate conglomerates. The aesthetic realism they favor is connected to an acceptance of a liberal world order of capitalism and nationally representative democracies. The right, meanwhile, in India and in the West, favors fantasy, myth, and conspiracy narratives. I wanted a radical, utopian aesthetic, one that could take on the eerie, phantasmagoric, apocalyptic conditions of the world today—its viruses, fascist strongmen, brain-altering media networks, and climate disaster—without succumbing to right-wing fantasia or to the “this is the best of all possible worlds” dogma of liberal realism.

FR: Tell us a bit more about Bibi, one of your main characters, who is from Shillong and works for the think tank named Amidala in New Delhi of the near future. You are also from Shillong and are, well if not a former journalist, a current one. What drew you to write her with these parallels?

SD: Bibi is the character closest to my heart. She is also the most important character in the novel because we begin with her, and it is from her perspective that we see the apocalyptic, near-future, slightly alternative Delhi that is eerily similar in many ways to the present-day Delhi. I’m always drawn to marginal protagonists, people who don’t quite belong, who are outsiders but who have the privilege and misfortune to be operating on the inside. Bibi is from my hometown, many thousands of miles east of Delhi; her family history spills over the boundaries of nations; she is a middle-aged, single woman, lonely, peripheral, and filled with an acute sense of failure both personally and in terms of the larger trajectory of the world. There are other aspects of marginality to her, but they are to be read between the lines. Bibi also captures something of my own existence in New York, my own sense that having moved thousands of miles, I still don’t quite belong. Like me, Bibi is alienated from nationalism, from capitalism, from the loud, triumphal roar of profit and power. She is, to use the nomenclature of the American bureaucracy, an alien. Having said all that, I have also had to let Bibi reveal herself to me gradually. A character has to exist on the page beyond my own conscious intentions, and to a great degree, in writing about Bibi, I was following her as much as she was following me.

FR: Let’s talk about a character that is very much not like you: the narrator of the second novella, a hitman who arrives in Bhopal just before the lethal gasses from the American chemical factory go on to kill thousands and who is consumed by a politics of misogyny and hyper-nationalism. How did you come across such a character? Did he also find you as much as you created him?

SD: It was disturbing that such a man announced himself to me when I was writing the novel, even if when I met him, all I knew at that point was what the reader knows of him, that he is sitting in a second-class train compartment, that the year is 1984, that he has participated in the orgy of violence toward Sikh minorities in Delhi and is on his way to Bhopal on the orders of his secretive patron. But he is also very much a character of the present. Complacent, contemporary literary sensibilities seem to believe that everything from Donald Trump to Narendra Modi are discrete phenomena, to be picked up and discarded as we move through time. But they have long been around—and this character is one example of that. It was not as if right-wing Hindu nationalism just showed up with Modi and the massacre of Muslims in Gujarat in 2002; that was preceded by the killing of Sikhs in 1984 by the Congress Party that is today in opposition to Modi’s Hindu right party. Similarly, today’s climate collapse and the pandemics and emergencies of our own moment were foreshadowed by the spewing out of methyl isocyanate gas in Bhopal (4000 dead in 24 hours, over 20,000 dead in the next two decades) in 1984 and the indifference of western corporations and western governments as well as of Indian elites to that suffering. Past, present, and future are connected together in intricate ways.

FR: Politics is central to the novel and yet how do you tell a story without allowing politics to subsume it? How do you balance offering a narrative about ideas and ideology and conveying the complexities of human experience? I am thinking of Bibi who acts in plays based on the life of Bhagat Singh but I am also thinking about the assassin in whose life, despite the toxicity, there are moments when he feels vulnerable: he also wishes to be loved.

SD: The most ideologically steadfast of my characters is Magadh, the assassin, whose nationalism and misogyny has the least room for doubt. But he is, at the end of the day, a low-ranking killer for powerful forces, and ultimately, he too is human, vulnerable. I don’t think I would be able to write fiction, or for that matter, nonfiction, if I didn’t value human ambivalence and the craving for love. Love is what drives our desire for a political utopia (I’m not with Hannah Arendt when she says, somewhat conveniently, that love is the most anti-political of forces), and Bibi’s desire for love is, in all her doubts, fear, and self-loathing, inseparable from her desire for collective forms of justice and liberation.

FR: In addition to creating compelling characters, you vividly evoke the historical milieu within which they move. But instead of thriving on a glorified, nationalistic idea of what happened in India’s recent past, you capture the mood engendered by the excesses and absurdities of history. Could you speak about that, citing examples from the third and fourth novella in your book?

SD: The third novella, Paranoir, is set in 1947 in Calcutta, just before the apocalyptic violence of the Partition and just after the equally apocalyptic violence of the Bengal Famine, while the fourth novella, The Line of Faith, is set after the brutal end to the Sepoy Rebellion of 1857. These are forgotten moments today, except for when they are ushered into neat, nationalist narratives. I wanted to step away from both the glorified, self-serving versions of the past produced by the Hindu right, which functioned largely as a collaborating wing of western colonialism, but also the liberal, nationalist version of the idea of India, its faith in what Perry Anderson critiqued as “antiquity-continuity.” I was interested, instead, in rupturing the fabric of such understanding or such forgetting, of stepping into the violence of the past but also then bending the narrative away from realism towards the horizon of the speculative and the weird. That is why Paranoir is about psychoanalysis and theosophy even as it is about famine and genocide, and why The Line of Faith is about automatons, aliens, and mountains, while also being about colonialism and race.

FR: Your first two novels came out in close proximity to each other. I know this novel took much more time to write. What kept you going over those many years—and especially in our own troubled times?

SD: I try to write from a place of freedom even when I feel that my life is unfree in so many ways. It took seven years to write the book, but the writing was done mostly in the summer because of a punishing teaching schedule, significant journalistic work, and life-affirming single parenting. But whether I was writing at home in Harlem with my son reading in the background or during summer travel somewhere, I knew I was trying to write the novel that I have long been wanting to read, a book that could be inventive and playful while plunging deep into pain and anger, something that was about South Asia but was also about the world, that was about the present but also refracted through past and future. I learned a lot about how much I loved the process, the discipline, and the practice of writing, and I learned that no one can take that away from you, even in a world as unfree and unequal as ours.

FR: To conclude, I wanted to go back to Bibi who sets out to find a missing journalist colleague. I see much of what is happening in India refracted through the pages of your book here. But how do you view the journalist’s disappearance and the journey Bibi makes to find him toward the end of the novel? For whatever reason this story, set mostly closely to our present, is the one that seems less directly about it.

SD: One of the goals in this novel was to be both about the present and also about a perpetual present, to be about India but also to be about the world, to be about the immediately political and yet also to be weird and speculative. This is a novel about the anthropocene and the final section is really about bringing the ends of the world and the end of India to a kind of intersection, to the realization that we are haunted by the displacements and violence visited upon us by history, which has not stopped and is instead arcing towards the apocalyptic. This haunting—this is a section filled with doubles and echoes, literal and metaphorical—happens in ways that can’t be grasped just by notions of trauma or resistance and instead has to be explored through questions of love, art, solidarity, and the yearning for freedom.