Radu Jude’s Wild and Caustic Films

His latest, Do Not Expect Too Much From the End of the World, is a a digressive and transgressive movie of ideas about the social-media age.

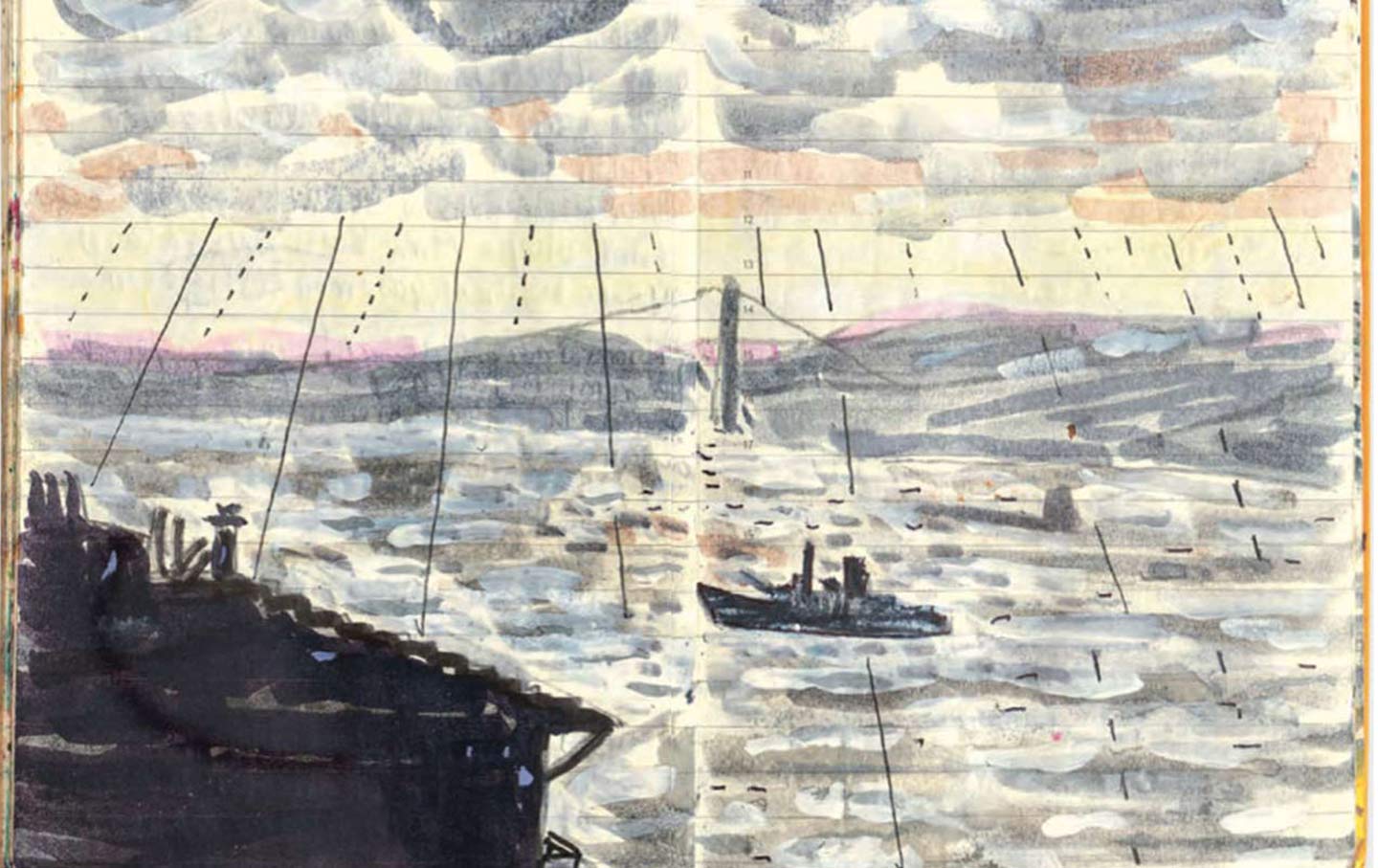

A scene from Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World.

(4 Proof Film)The author of the world’s first great sex-tape/Covid/cancel-culture comedy Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn, the Romanian writer-director Radu Jude now issues us a warning in Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World. The sardonic title, which could refer to the end of communism or capitalism or both or neither, comes from a phrase found in the Cold War writings of the Polish-Jewish communist and then excommunist aphorist Stanisław Jerzy Lec. Jude applies it to the situation in which we find ourselves—the erosion of civil society and rational discourse promoted by the utopian promise of the Internet. Not that he doesn’t also revel in the chaos. “I have all the social media apps,” he told an interviewer.

Indeed, given Jude’s willingness to engage with (or disinclination to disengage from) the cyber-powered second life, Do Not Expect is more despairing if even funnier than Bad Luck Banging. Riding shotgun through Bucharest beside an overworked, underpaid, sleep-deprived thirtysomething freelance production assistant, Do Not Expect is a journey less to the end of the world than to the end of the night. Here as in Bad Luck Banging, Bucharest is an unlovely urban nexus of mindless energy and aggressive fantasy.

Long hair pulled back and features pushed forward, heroic Angela (Ilinca Manolache) suggests the figurehead on a ship’s prow as she fearlessly navigates a stormy sea full of noisy traffic and hostile fellow drivers. Exploited and exploiter, Angela is both inside and outside the movie on which she is working. Her sparkly minidress is as incongruous as her incessant cell phone ringtone (the first eight notes of Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy,” since 1985 the EU’s “Anthem of Europe”). Her job is to audition individuals who have suffered a serious work-related injury and, if chosen, will be paid to appear in a movie promoting worker safety.

The project seems reminiscent of the old TV show Queen for a Day, where contestants competed in tales of woe, with the audience determining whose distress was most worthy of the grand prize. But there’s more than one way to monetize misery. The Austrian outfit bankrolling the film is interested less in ameliorating conditions than in selling worker-safety paraphernalia of dubious value.

The first two hours of Do Not Expect are nonstop turbulence. Jude throws the spectator into the maelstrom. His audience is left to either sink or swim. For reasons not immediately apparent, Angela’s tour of duty is interwoven with footage from two other films: One is Lucian Bratu’s 1981 Angela Moves On, another ride-along Bucharest travelog with a single working woman, in which the namesake protagonist (Dorina Lazar), a middle-aged divorcee, supports herself by driving a cab. Although the movie was shot during a period of severe austerity, Angela’s problems have less to do with economic hardship than with problematic men.

The other, far more aggressive strand consists of a crude, belligerently sexist TikTok starring Angela’s male avatar and alter ego, Bobita. Created by Manolache during Romania’s Covid lockdown, Bobita is modeled on an actual person, namely the Anglo-American influencer Andrew Tate, indicted in Romania last year for human trafficking.

Bobita personifies the excesses of social media. Angela Moves On, made during the reign of Romania’s communist dictator Nicolae Ceauşescu, is an example of what Jacques Ellul called “sociological propaganda.” Shot in color and accompanied by blandly cheerful music, it focuses on a personal problem to paper over a much larger social one. Bobita’s ravings, by contrast, compensate for social weakness by exulting in (or parodying) illusory domination.

Thus we move from the falsehoods of the 1980s to those of the 2020s and back again. Jude orchestrates match cuts or slows down the older film to accentuate moments of inadvertent vérité—food lines, decrepit construction sites, people glaring at the camera. Yet, for all its sanitized reality, Angela Moves On also affords a flashback to the charming old neighborhoods that were eventually leveled so that Ceauşescu might build his monstrous Palace of the Parliament. Meanwhile, erupting out of the internet id, Bobita is another sort of horror, satirizing the anarcho-egoism the dictator reserved for himself.

Do Not Expect is a movie of ideas—a digressive, transgressive essay on the business of image production. Lazar’s Angela comforts herself watching an old movie romance (none other than Casablanca) on TV; Manolache’s Angela uses her alter ego Bobita to express mindless aggression. Bobita is mirrored by the bluster of German director Uwe Boll, maker of cheap, artless genre films, whom (sent by her cheapskate employer to borrow some camera lenses) she interviews on set. With references that span movie history from the first Lumière films to the death of Jean-Luc Godard, Do Not Expect becomes a celluloid Moebius strip in a scene where the two Angelas meet.

Nothing if not topical, Do Not Expect frequently refers to the Russian-Ukrainian war and the British royal family. (Evidently, King Charles owns multiple properties in Transylvania.) Crosscutting and cross references are the film’s organizing principles. Two scenes involve the necessity of disinterring Angela’s grandparents (a chunk of their cemetery’s land rights have been purchased by a glitzy hotel) and presage a lengthy sequence of folk-art roadside crosses marking highway deaths.

A monument to the absurd, these vernacular memorials also serve a weirdly bucolic interlude to another sequence in which Angela drives from the airport having collected Doris Goethe (Nina Hoss), a representative of her Austrian employer and hence her European overlord, in which the two conduct a conversation, of course in English, rife with comic misunderstanding. Jude has suggested John Dos Passos’s USA trilogy as his model, but the American writers he more closely resembles are the ruthless satirists William Burroughs and Mark Twain.

Having juggled three movies, Do Not Expect ends with a fourth. After two hours or more of constant motion, the action grinds to a halt. In a single 40-minute shot, taken from a fixed camera position, the scene of the designated injured worker, surrounded by his family, is rehearsed, filmed, and refilmed—the crew heard more than seen—until the injury is mitigated, the hazardous work conditions are dispelled, and the blame shifted from the employer to the injured party.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Watching remotely, another sort of angel, Doris Goethe, oversees the shoot, while, among other random disruptions, Bobita butts in to praise Putin. The director mollifies the family with empty assurances that their truth will be told even as the injured man’s testimony is obliterated. Mission accomplished; the crew breaks for their free lunch. The movie’s last words: “Let’s go. Fuck these bastards.”

Jude was 12 when Romanians ousted Ceauşescu and is thus of an age to have experienced childhood under the rule and adolescence after the overthrow of a singularly inept and destructive regime. A product of corrupt socialism and brutal neoliberalism, he seems to have reached a neo-Marxist position that recognizes the social order as a matter of bait-and-switch promises and dog-eat-dog manipulation.

This caustic comedy, at once outrageous and outraged, might be subtitled The Indignity of Labor, garnished with a few of Bobita’s choice expletives. It is not work but exploitation itself that creates surplus value in the gig-driven postindustrial society of the spectacle.

More from The Nation

Can You Understand Ireland Through One Family’s Terrible Secret? Can You Understand Ireland Through One Family’s Terrible Secret?

In Missing Persons, Clair Wills's intimate story of institutionalized Irish women and children, shows how a family's history and a nation’s history run in parallel.

Peter Schjeldahl’s Pleasure Principle Peter Schjeldahl’s Pleasure Principle

His art criticism fixated on the narcissism of the entire enterprise. But over six decades, his work proved that a critic could be an artist too.

How the Western Literary Canon Made the World Worse How the Western Literary Canon Made the World Worse

A talk with Dionne Brand about her recent book, Salvage, which looks at how the classic texts of Anglo-American fiction helped abet the crimes of capitalism, colonialism, and more...

Along the Roads That Built Modern Brazil Along the Roads That Built Modern Brazil

José Henrique Bortoluci's What Is Mine tells the story of his country’s laborers, like his father, who built its infrastructure, and in turn its fractious politics.

The Long History of the "Elsewhere Museum" The Long History of the "Elsewhere Museum"

Can the ethnographic museum be reinvented?

Rain and Mountains Rain and Mountains

Pages from a novelist’s notebook.