Double Agents

Rachel Kushner’s high-art spy thriller.

Rachel Kushner’s Brilliant Avant-Garde Spy Thriller

In Creation Lake, Kushner transforms the genre’s familiar plot twists and turns into a study of the many fictions we tell one another.

In a 1974 essay on the poetry of Luis de Góngora, the high priest of the Spanish Baroque, the Cuban novelist Severo Sarduy coined the concept of la metáfora al cuadrado—metaphor squared, or metaphor to the second power. Writing in a period of imperial decline, Sarduy explained, Góngora turned metaphors on their head, hoping to make them new and find vitality in an era of attenuated exhaustion. Where a lesser poet might write that “water is crystal,” Góngora would instead write that “crystal is water.” Looking for his materials in the “eroded, already gnawed-on terrain” of a flagging Spanish empire, he had to refashion the conventional and clichéd into the strange and unfamiliar, even the nonsensical. The result, Sarduy noted, was that Góngora unleashed a “geometric multiplication of metaphor”: His rhetorical figures presumed that the reader was familiar with the tropes of a worn-out poetic canon that he at once rejected and embraced. Along the way, according to Sarduy, Góngora took an already perverted language and made it even more perverted. Figuration no longer needed a referent; at the center of his metaphors there was nothing but other metaphors.

Rachel Kushner’s extraordinary new novel, Creation Lake, is a worthy heir to this tradition of linguistic deviousness. Set in present-day France, the book delivers, among other things, a parody of contemporary French fiction and theory, a meditation on the promise and peril of radical politics, an elegy for the soon-to-be-lost way of life of small European farmers, reflections on both modernity and prehistory, accounts of medieval peasant revolts, climate anxiety, white wine, sex, violence, betrayal, and an ars poetica whose central metaphor figures the novelist as a kind of secret agent: a liar who seduces the reader by pretending to be someone else.

There’s nothing baroque about Kushner’s prose, which is full of tension and clarity and as far removed as imaginable from Góngora’s impenetrable metaphors. Yet many of her gestures conjure a doubling effect not unlike the one that Sarduy described. Her new book is a spy novel raised to the second power. It’s not just that Creation Lake is a fiction about a secret agent; it’s that the secrets this agent carries with her are often themselves fictions—she is as much of a novelist as her creator. The result is that the referents that would ground the novel in the real world disappear swiftly into a hall of mirrors, until nothing but the power and profundity of language remains. If Plato wanted us to step outside the cave of deceitful rhetoric and into the sunlight of transparent truth, Kushner makes an argument for stepping further into the cavern, where the dancing flames of a torch can afford us a different kind of revelation.

Creation Lake is like Góngora’s poetry in another way as well. Working in a period of imperial decline not unlike that of the Habsburg Empire, Kushner turns to a novel full of squared language in part because she, too, has to breathe new life into gnawed-on materials. In order to write a spy novel in an age exhausted by spies and geopolitical intrigue as well as novels about them, she has to find new meaning in the girl, the lie, and the guns of an espionage thriller. Her task is to make new the tired story of the American ingenue who goes to Europe only to find herself in over her head—an archetype that the left misogynists of the French journal Tiqqun, who seem to be the target of some of Kushner’s most biting satires, christened as “the Young-Girl”: an emblem of the ideology of infantile optimism that the United States imposes on the world to preserve capitalism.

It goes without saying that Kushner knows that women are not girls and that girls are not idiots—a substantial part of the knowingness of her novel is found in her critique of a left (in this case, a French left) that may not have gotten that memo. But Creation Lake is equally withering when it comes to American myopias. Just as the metaphor of the Young-Girl does not fit its referent, the America that Kushner’s protagonist personifies is no longer young and full of promise but jaded, cynical, and amoral. Though her narrator has yet to enter middle age, there is nothing innocent about her or the work she does on behalf of capital. This is the ultimate fiction dissected in the novel: the neoliberal story that the United States and its European imitators tell themselves in hopes of passing off as progress the destruction of both culture and nature in the pursuit of profit.

Books in review

Creation Lake

Buy this bookThe bare bones of Kushner’s plot are as follows: Sadie Smith leaves her graduate studies in an unspecified humanistic discipline, first to become an undercover asset for the FBI and later to work as a freelance secret agent. At the behest of a mysterious cabal of capitalists, she seduces a wealthy Parisian filmmaker under an assumed identity in order to gain access to his best friend, a charismatic leftist who leads a radical commune in rural southern France. Her mission is to infiltrate the commune and find out whether its members are responsible for recent acts of sabotage against the agro-industrial corporations that are rapidly displacing the region’s embattled small farmers—as well as to encourage the radicals to commit a serious crime that will attract the attention of the authorities and put an end to the commune: the murder of a mid-ranking bureaucrat who, for reasons that are never made clear, represents an obstacle to the capitalists’ goals. After nearly 400 pages, Sadie fulfills the terms of her assignment, although not in the way that she had planned.

In the hands of a writer as accomplished as Kushner, this formulaic plot, worthy of a mediocre action movie, might be enough for a riveting novel. But Creation Lake takes this story and turns it on its head. The novel’s status as a thriller is itself a deception, a sleight of hand, the outermost layer of a Russian nested doll of deceit. The novel’s first-person narrator, after all, is a specialist in lies, gaslighting, and manipulation—an expert in fiction. As we make our way through the labyrinthine acts of surveillance and rapport building that allow her to carry out her mission, we also begin to doubt the very veracity of the story that she is telling. We realize that what sets her apart from James Bond or the other members of her secretive guild is that Kushner’s narrator is more than merely unreliable: She’s a creator of fiction as well as a creature of it.

The geometric multiplications go even further as we move deeper into the maze. Though we are told that our hero is named Sadie Smith, it turns out this isn’t her real name (which we never learn), but that of the fictional persona she adopts to fool the radicals. The referent once again falls away, and all that we are left with is the figuration: a character who pretends to be a character who pretends to be a character. Sadie’s work of deception is so recursive that we aren’t sure what is true and what isn’t in the novel—who she is and who she isn’t, what she’s willing to do for money, and what lies she might be telling, not just to her targets but also to herself and therefore to her readers. It’s no wonder that the name of the bureaucrat she’s been tasked with eliminating is, of all possibilities, Platon, the French spelling of “Plato.” The poets and novelists, Kushner seems to be telling us, have infiltrated the city, and they will waste no time in getting rid of the philosopher who first sounded the alarm against the dangers of figurative language.

I worry that by highlighting Kushner’s Borgesian labyrinths, I’ve made Creation Lake sound as boring as the French theory it parodies. Let me assure you that it is, in fact, incredibly fun. It provides the page-turning suspense that one expects from any effective thriller, but its many highbrow jokes include a send-up of Michel Houellebecq in a character called Michel Thomas, who accompanies Platon to the agricultural fair that serves as the setting for the novel’s climax in order to gather material for an “agronomy novel” that resembles Houellebecq’s Serotonin—a text with which Kushner’s book is obviously in conversation, or perhaps in competition: Both novels culminate with acts of violence committed during protests by dairy farmers angry with the economic policies of the European Union.

Books in review

Creation Lake

Buy this bookBut Creation Lake succeeds for another reason as well: Its narrator is one of the most charismatic characters I’ve ever encountered in contemporary fiction. I’m embarrassed to admit it, but it has been a long time since I found myself falling in love with a person that doesn’t exist. I resent Kushner almost much as I admire her: She’s such a master of deceit that she succeeded in making me regress to the kind of reader I was as a child, when I wished that the people who inhabited the novels where I took refuge from real life were creatures of flesh and bone rather than amalgams of words.

Sadie Smith is every bit as unsentimental as one would expect from an amoral mercenary willing to do the bidding of evil capitalists, but she’s also a keen observer of people and places and in possession of a deadpan sense of humor. She’s just as capable of a lyrical description of the play of the sun on the leaves of walnut trees as she is of a devastatingly acute mockery of haute bourgeois Parisian boys so thoroughly ruined by grande école intellectual gymnastics that they’ve managed to convince themselves that delegating the childcare, cooking, and cleaning to their female comrades, all so they can spend their days corresponding with a cave-dwelling philosopher obsessed with Neanderthals, is good feminist praxis. Such steely-eyed satire appears throughout the book; much of the pleasure of spending time with Sadie comes from watching her peel the layers of people’s personalities to reveal their pathetic core, even while she studiously refuses to reveal her own.

This pleasure, however, is itself a product of her talent for deception. Sadie knows everyone; she can get behind their surfaces and tells us about their essences. Yet real human beings are mysterious: We think we can get to know them, but we can never truly plumb their depths. Sadie, however, convinces herself—and us along the way—that she understands what makes all of the people around her tick by turning them all into her creatures. This is Sadie’s final act of deception: She transforms the world around her, vivid and plausible as it is, into a stage for her own performance. The Parisian boys obsessed with Guy Debord; the philosopher-bureaucrat who would expel the poets from the city and drag the farmers out of their primitive caves and into the neoliberal sun; the anarcho-communist clochard who has made her home in the ruins of the local castle—all of them exist primarily to give Sadie occasions to exercise her novelistic talents. They are not real but rhetorical, not figures but figurations: language that brings forth nothing but a further profusion of language.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →All of these recursive gestures and metaphorical reversals could risk becoming a bit tiresome, but Kushner is too wise—or too wily—to fall prey to the metaliterary temptations that have been the bane of countless imitators of Miguel de Cervantes and Miguel de Unamuno. Beyond the playful names of some of its characters, the surface of Creation Lake, like its protagonist’s persona, never breaks character; the novel’s studious commitment to realism and plausibility is perhaps its most devious and successful deceit.

And yet, every so often, Kushner lets her narrator drop her persona, allowing Sadie to briefly exist outside the intricate web of her fictions. This unmasking happens when Sadie takes a lover from among the members of the commune. The attraction she feels for him, we are convinced, is real; the pleasure she gives him is real; the fury she experiences when he slaps and chokes her after his wife discovers their affair is real. The same goes for the disgust that overwhelms her each time she acquiesces to having sex with the naïve and pompous rich-kid filmmaker she pretends to be in love with in order to gain access to his best friend, a Debord wannabe who comes from old money—and who also, as is often the case, happens to be the charismatic leader of the cultish commune.

We get an even clearer view of the real person who hides behind the persona of Sadie Smith when we witness her growing admiration for the cave-dwelling philosopher who mentors the insufferable boys. Just as Michel Thomas seems to be a stand-in for Michel Houellebecq and the communards seem to be based on the Invisible Committee, Bruno Lacombe is clearly a cipher for Bruno Latour, though his ideas and the way he lives them out—renouncing technology and, in a comically literal-minded refutation of the allegory at the heart of the Republic, moving into a cave in hopes of reconnecting with humanity’s Neanderthal heritage—differ substantially from those of the author of We Have Never Been Modern. A war orphan who was once part of Debord’s crew of hard-drinking street urchins, Lacombe has concluded that there’s no point in trying to dismantle capitalism, that modernity’s race toward extinction cannot be stopped from within. The only option, he writes in long e-mails to the insufferable Parisian boys, which Sadie reads after hacking his account, is to “leave the world”—to renounce society and relearn the lost wisdom of our earliest ancestors, who, unlike us, knew how to live.

Here we see Sadie being honest for once: For all her jaded cynicism, she too is heartbroken to have discovered that the world outside the cave is nothing but a world of lies; that she is dissatisfied with her life of recurring betrayal and recursive deceit; that more than money or freedom or even pleasure, she longs for something true, something decidedly unrhetorical, something older than figurative and even referential language.

After her plan to sabotage the commune and get rid of Platon fails at the last minute, only for things to nonetheless go her way thanks to a stroke of dumb luck, she decides to embrace Lacombe’s Paleolithic imperatives—though her version of the cave is admittedly rather more luxurious than the philosopher’s. Instead of heading to her next assignment, she takes her exorbitant earnings from the French job, buys an expensive car, and drives to a remote seaside village in Spain. She looks at the stars, swims in the sea, quits drinking, talks to virtually no one—and finds something like peace. She no longer has to pretend to be someone else to gain people’s trust and then betray them. Like Lacombe, she has left the world she has created and entered a new one—a world no longer of her making and therefore real.

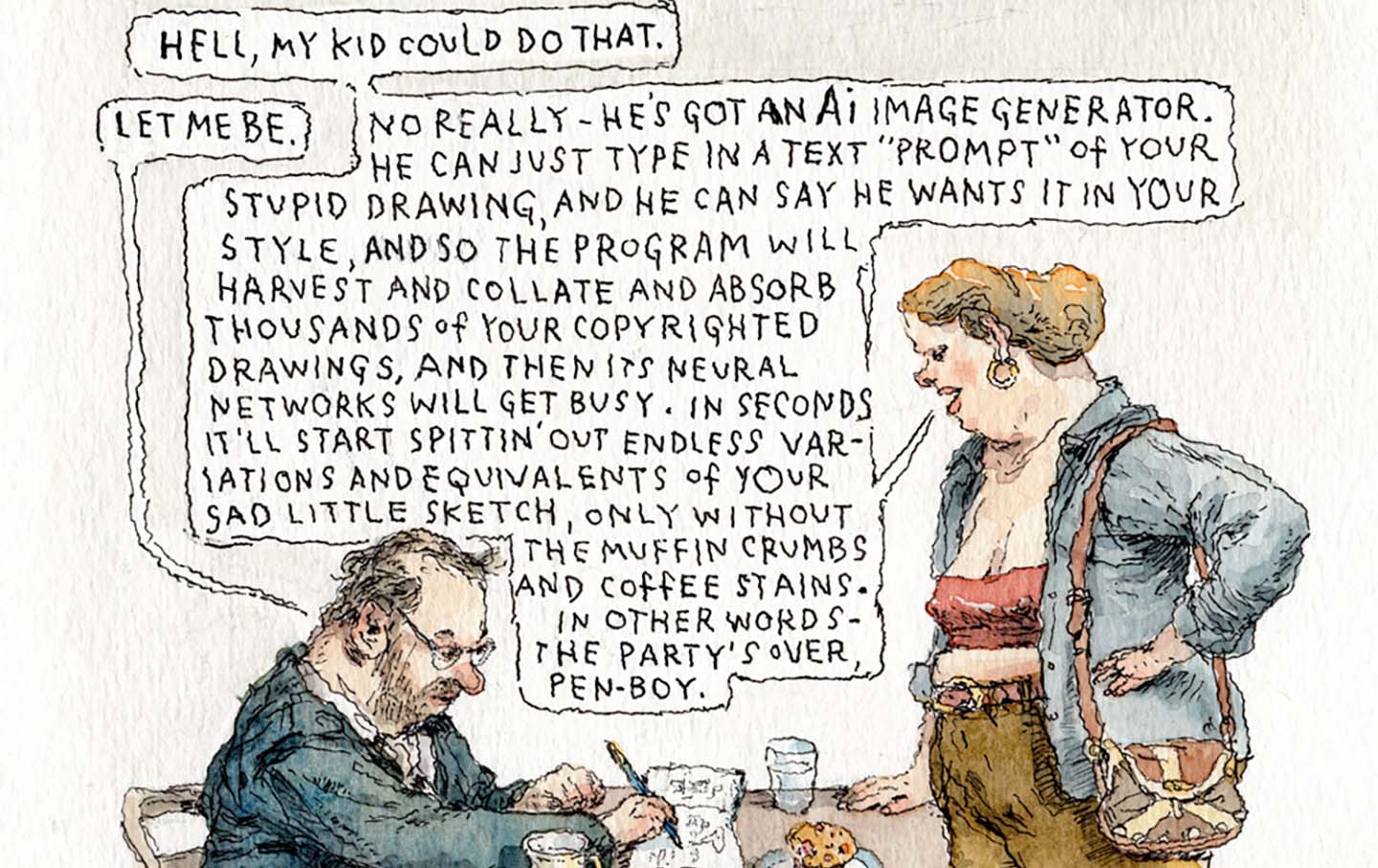

Except, of course, that it isn’t. Sadie Smith may have abandoned her calling as a weaver of fiction, but Rachel Kushner never does. The relief we experience as we witness the understated redemption of our antihero—so vivid and compelling that some of us wound up developing an infatuation with her—is the novel’s final and cruelest deceit. We realize that Kushner has played us when we reach the final page and are reminded that all of it was a lie. Much like the communards whom Sadie seduces, we’ve been fooled by the unhealthy and unnatural power of figurative language—the power of the novel and its capacity to create entirely fictional worlds. This moment of betrayal is when Kushner’s stature as an artist becomes clear. After entrancing us for 400 pages, she unceremoniously drops us back to earth and reminds us that she, too, is a secret agent: a practitioner of the dark arts of fiction raised to the second power.