Chronicles of Freedom

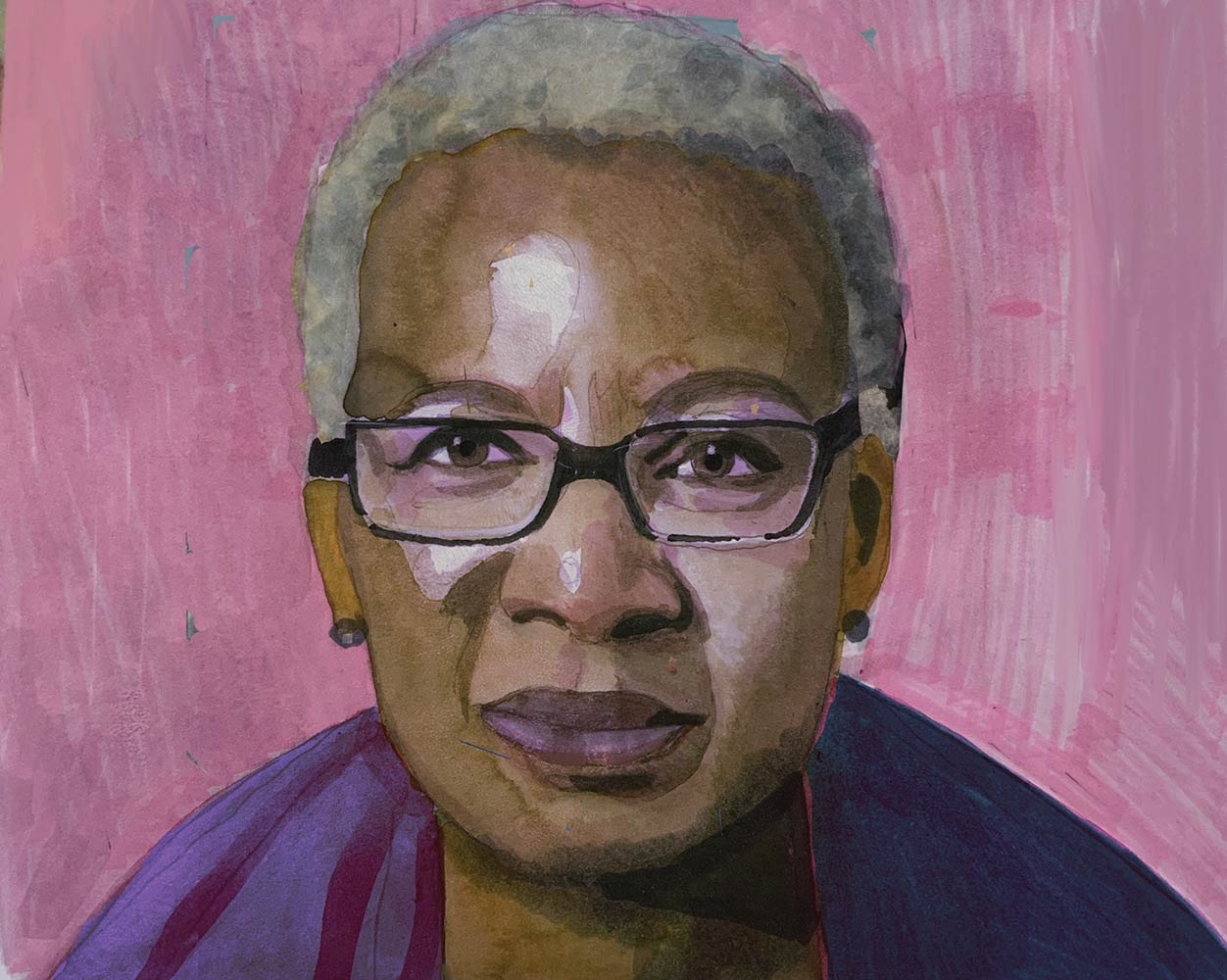

The radical histories of Nell Irvin Painter.

Nell Irvin Painter’s Chronicles of Freedom

A new career-spanning book offers a portrait of Painter’s career as a historian, essayist, and most recently visual artist.

On May Day in 1933 in Birmingham, Alabama—a state that then had an unemployment rate of 25 percent—an unemployed committee held a mass meeting of Black and white workers. One member stood on a postal truck and addressed the crowd. A cop told her to stop. Several people chanted, “Let her speak! Let her speak!” The woman was soon joined by a Black man named Hosea Hudson, a member of the Communist Party. Then another man lent his voice to hers as well and hit the police officer in the head with a stick. Several plainclothes cops restrained the man; one took the stick and prepared to hit him with it. Hudson wrested the stick away and then was struck by a cop’s blackjack. “I buckled,” Hudson later recalled, “but I didn’t fall.” Soon a full-on altercation had broken out, and yet even in a potentially deadly encounter with the police, the attendees of the mass meeting risked their lives to protect one another and to preserve their right to assemble.

Books in review

I Just Keep Talking: A Life in Essays

Buy this bookFrom the vantage point of the present, in which the police seem especially lethal, the story is surprising. One imagines hearing it, as Nell Painter did when Hudson recounted it to her in the late 1970s for the oral history they were writing together, and being as awed by the resilience of Hudson and his fellow workers as she must have been. At the time, Painter was an accomplished thirtysomething historian who had already completed her first book, on Black migration to Kansas after Reconstruction. But as she began work on a second book, she heard about Hudson from Mark Solomon, a historian of interwar Black communism, and traveled to Atlantic City to see Hudson herself. Interviewing him until her tape ran out, Painter soon returned to conduct more interviews and eventually compiled them into The Narrative of Hosea Hudson: His Life as a Negro Communist in the South. In its tales of Communist Party organizing, surviving police repression, and more, the book exemplified a signature contribution of Painter’s historical scholarship. Whether in her histories of Black life during the rollback of Reconstruction or of the development of whiteness as a racial category, Painter has put the agency of her subjects at the center of her work, even—or perhaps especially—when they were under assault.

Now, in her new book, I Just Keep Talking: A Life in Essays, Painter clarifies the reasons for her insistence on chronicling survival amid violence (and the violence that makes survival necessary). Compiling visual art, autobiographical writings, historical essays, and journalistic pieces completed between 1981 and 2022, the collection marks the contours of Painter’s personal and professional development. In the tales of her middle-class upbringing and the radical student body she became a part of during her college years at the University of California, Berkeley, and in the examinations of her earlier historical scholarship and her later years as an artist, I Just Keep Talking provides a grand and capacious vision not just of Painter’s life and times but of Black history and culture, too. Painter not only critiqued anti-Blackness but also examined Black people as subjects of history. She wrote sweeping political histories, numerous essays (including for this magazine), and even became a celebrated visual artist.

Painter’s early experiences with diverse kinds of Black people in both North America and Africa had long made her want to seek out a historical approach that would capture the vicissitudes and varieties of Black history. Her aim, she writes, is to find historical “specificity—individual specificity, geographical and chronological specificity—rather than generalization; as I read the past, one person cannot simply be substituted for another merely on account of sex or race.”

This insistence on concrete differences and on the agency and subjecthood of Black people in the United States shapes her understanding of the history of race. In her work, the local meaning of Blackness depends on the time, place, and people studied; for Painter, “mine is a Blackness of solidarity.” Like Cedric Robinson in his chronicles of enslaved people’s rebellions in Black Marxism, and like Carole Boyce Davies in her writings on Claudia Jones in Left of Karl Marx, the essays, memoirs, and art of I Just Keep Talking attempt to offer not only a vision of the past but also a collectivist politics for the present. The solidarity that the latter exemplifies—one that seeks common cause across difference—still has much to teach.

What this collection also adds is insight into Painter not only as a historian but as an artist. In her mixed-media collages, drawings, and more, she juxtaposes the insights of her scholarly life with those of the new vocation she found after she retired as a historian. Alongside an essay on the formerly enslaved woman Harriet Jacobs is Painter’s ink drawing of the title page of Jacobs’s book and her runaway poster. In an essay on Martin Delany, the 19th-century Black writer and physician who once sought to bring Black Americans to Africa, she includes a collage representing Delany’s midsection and a kind of map of a region in Nigeria. That piece places the author within his failed political aspirations, making visible his prior liberatory imagination. It is also indicative of Painter’s own vision of art. She writes of one set of her paintings:

The fundamental personal quality of my work [is] freedom. Freedom from archival truth, freedom from clear meaning. The freedom of late style to play with composition, figures, color, and space. Freedom to find new narratives or make images with little narrative coherence. After a lifetime of expressing complicated notions clearly, I revel in the freedom to follow my visual impulses.

Perhaps most of all, this is what unites Painter’s work as an artist and her work as a historian: a driving and unyielding interest in freedom—one documented not only through chronicling oppression but also through examining new and potential meanings for emancipation.

Nell Painter (née Irvin) was born in 1942 in the Houston Hospital for Negroes. Her parents had met at the Houston College for Negroes, and shortly after her birth, they moved to Oakland, California. As Donna Murch has written, westward migration offered Black Southerners new economic opportunities, but it also offered Painter’s family something else: In California, “Oakland’s traditional progressivism” and her “parents’ awareness of the meanness of Texas politics” led them to left-wing politics. “We read Freedomways and The Nation,” Painter writes, “admired W.E.B. Du Bois and Paul Robeson, followed the Highlander Folk School, and were among the first to join the Berkeley Food Co-Op.”

Painter’s parents also took an interest in “the counter-art-historical tradition of Black American modernism, as in the work of Aaron Douglas, Charles White, Jacob Lawrence, and Elizabeth Catlett, my father’s favorite artist.” Conversely, her family disdained “conspicuous consumption” and the Black bourgeoisie. Though her parents’ middle-class position provided Painter with physical and economic safety, their politics ensured that she always looked outward.

This relative class privilege and leftward bent gave Painter, to use Toni Morrison’s phrase, a source of self-regard. Though her family experienced housing discrimination and “occasional difficulties in getting decent service in restaurants,” her father’s position as chief technician of chemistry at UC Berkeley also offered them financial stability. As Painter recalls in one essay in I Just Keep Talking:

My childhood’s safety…endowed me with resources that I recognize now as resilience. I’ve been able to remain relatively optimistic in my character, as opposed to fundamentally anxious or fearful of injuries familiar from hurtful experience…. I always knew beneath the surface of my consciousness that disregard was not a correct appraisal of my worth, of my intelligence, of the soundness of my thinking and my being.

If Painter’s homelife provided a sense of self-worth, school provided new opportunities. She attended Oakland Technical High School at the same time as Huey Newton, when racially selective class placements internally segregated their school. One of the few Black students in AP classes, Painter dreamed of going to Howard until the sociologist E. Franklin Frazier joined her family for dinner one evening. Frazier considered her a poor fit for the Black Ivy; Painter presumes that this was because the women enrolled at Howard at the time were understood to be courting husbands. “Nell Irvin,” Frazier told her, “you are too smart and too dark to go to Howard.”

Whatever one might think of this advice, Frazier’s intervention did lead Painter to forgo Howard and instead enroll at UC Berkeley, where she found new opportunities that transformed her racial politics. She spent time at the YMCA that once hosted Malcolm X, where she learned about Operation Crossroads Africa, through which she traveled to northern Nigeria in 1962. There, she met Black Muslims from a “part of the continent that I hadn’t known about before…. More reason not to be able to generalize about some all-encompassing Blackness.”

Berkeley also introduced her to a radical milieu. Painter “hung around the edges of a proto-Afrocentric movement, the Afro-American Association,” whose members included Cedric Robinson and whose organizing inspired Huey Newton and Bobby Seale to establish a similar group at nearby Merritt College. But Painter was not a perfect fit for the Afro-American Association. “Like so much Blackness back in those days,” she recalls, “the racial default was male.” Whether by push or by pull, this realization led her to seek out a more heterogeneous Black radicalism too.

Her continued travels compelled Painter to find a focus in her search for diversity among Black people: class. After graduating in 1964, she joined her parents in Ghana, where she noted upon arriving that “everyone was Black, an even, opaque, velvety Black that I had never seen in the United States. The customs officials, families greeting passengers, taxi drivers, policemen, they were all intensely and beautifully Black…. The people in the airport not only looked different from American Black people; they also carried themselves differently.” In this predominantly Black country, Painter’s American understanding of race changed. “In the independent republic of Ghana,” she writes, “the issues were not racial, but economic”—for example, the question of whether the Ghanaian state should promote agriculture, which would lead to both profits for and the exploitation of Black people. Accordingly, Painter learned to think about the specificities of Black people not only in terms of gender but also in terms of class.

After the coup that deposed Kwame Nkrumah in 1966, the socialist-leaning Painter left Ghana and returned to the United States, where she earned graduate degrees in African and African American history at UCLA and Harvard and became an assistant professor at the University of Pennsylvania. Yet even as she climbed the ranks of the academy, discrimination followed her. At one lecture, a white stranger struck up a conversation with her and assumed that she was hired because of affirmative action. Later, after moving to North Carolina, her students complained that affirmative action stigmatized Black people. Reflecting on both experiences in 1981, Painter observed:

White people tell me I must be on easy street because I’m Black and female…. On the other side of the color line, every Black student knows that he or she is fully qualified—I once thought that way myself. It is just the other Black people who need affirmative action to get in.

Both experiences, in her account, reaffirmed “the same old White-male-superiority line, fixed up to fit conditions that include a policy called affirmative action.” Instead of protesting that she was qualified, Painter writes, she became “one of the few people I know who will admit to having been helped by affirmative action.” Two departments that had never hired Black people hired her. Rather than emphasize her own excellence, the ever-secure Painter saw the institutions that barred Black people—not Black people themselves—as deficient. As a result, she emphasized in print that affirmative action corrected institutions, not Black people.

For Painter, her identity and her biography had become sources of insight. The historian who had found travel revelatory and who came from parents who had fled the South turned to a familiar subject—migration—for her first book. Painter undertook research on Black Americans who left the South after Reconstruction and published her study as Exodusters in 1976. “People had tried to leave, and thousands had succeeded,” Painter recalls in I Just Keep Talking. But “more than forty years after the publication” of Exodusters, she continued to be haunted by those who remained—in particular, “a woman’s description of torture, of murder, in East Feliciana Parish, Louisiana,” warned “of what atrocities Americans are capable of.”

Painter continued to study the collective agency of Black people and the violence impeding their efforts to eke out better lives in her 1979 book The Narrative of Hosea Hudson, which chronicled Hudson’s activism in response to state repression and Depression-era exploitation as well as his dedication to organizing the interracial poor.

Even when Painter moved beyond the South, her work still carried those themes. In the 1989 book Standing at Armageddon, she tells the history of Reconstruction’s rollback by examining the violence of the Jim Crow regime and the ways in which Black Americans sought to survive its assaults. Meanwhile, in her 1997 biography Sojourner Truth: A Life, a Symbol, she emphasizes Truth’s contributions to the 19th-century women’s suffrage movement and also her influence on 20th-century feminist movements.

This twin focus on repression and resilience also shapes many of the essays, memoirs, and articles collected in I Just Keep Talking, whether in her discussion of Martin Delany, Harriet Jacobs, or her own life. For Painter, Black people are never homogeneous, and they are never strictly objects. Rather, they are always history’s subjects.

Late in her career, Painter began to turn toward the visual. After retiring from Princeton, she studied art full-time, earning a BFA at Mason Gross in 2009 and then enrolling in an MFA program at the Rhode Island School of Design, where she earned a degree in 2011. Like many other art students, she was self-conscious, unsure of the worth of her work, and subject to the mood swings of her professors. The publication of her New York Times bestselling book The History of White People during this time complicated matters even more. Shortly after she appeared on The Colbert Report to discuss the book, an art teacher named Irma visited her studio. “You can’t draw, and you can’t paint,” Irma told her, and then asked: “Why did you choose to go to graduate school when the biggest book of your career was coming out?”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →For a time, Painter internalized Irma’s criticisms and questioned her choices. But the Painter of I Just Keep Talking has found a renewed faith in her art’s relationship to her history. Looking back on her scholarly career, she notes that her aesthetic interest was foreshadowed by her writing on images of Sojourner Truth and by the juxtaposition of Black art and history in her 2006 book Creating Black Americans. And the visual, of course, also structures The History of White People. Though its examination of the social construction of whiteness debunks the easy association between phenotype and race, the book remains, in Painter’s words, “attuned to the importance of physical appearance.” Her 2018 memoir of her time as an art student, Old in Art School, further demonstrated that she could marry text, history (her own), and art. Her scholarship was not an impediment to her aesthetic practice so much as a source of strength underlying it.

This blend of artistic and historical interests sits at the center of I Just Keep Talking. Throughout, readers are confronted by the juxtaposition of the image and the written word. Text sometimes abounds in the art, as in her 2022 piece Same Frustrations, which depicts a journal with the words “same frustrations for 25 years” visible. As she argues in one essay:

Text, rooted in history, supplies one sort of meaning, while art, a work of imagination, conveys meanings that exceed the historical archive. They are not the same thing. It’s too simple to say that the text speaks historical truth, while art ranges further, reaches beyond the limits of the archive. But the contrast between what history says and what art suggests is well worth recognizing. History and art draw on two different kinds of power.

Painter may once have believed that her career as a historian undermined her later work as an artist, but now she sees the two as complementary. Her words and the words of others, and her art and the art of others, testify to one way to carve out a path of survival in the face of difficulty.

Like many late-career publications composed of an author’s uncollected works, I Just Keep Talking doesn’t offer an individual argument so much as a written and visual portrait of the author. Spanning over 40 years of publication, the essays represent Painter’s growth as a historian, as a writer and theorist, and as an artist. Her attention to race and gender, for instance, enables her to critique, in a 1992 essay, Clarence Thomas’s representation of Anita Hill as a villain, and these subjects resurface in a 2000 essay on how Harriet Jacobs used 19th-century assumptions about Black women to compel the reading public to oppose slavery. Throughout, Painter combines the historian’s concern for individual circumstance with an analysis of the relationship between power and identity.

Painter’s histories of the rollback of Reconstruction and the imposition of Jim Crow are especially prescient. In recent years, we have seen the Supreme Court roll back the Voting Rights Act and other gains of the civil-rights movement in ways that resemble the court’s late-19th-century backlash against the gains made by Black people during the Civil War and Reconstruction. The current court’s striking down of a constitutional right to abortion has likewise created a set of interstate conflicts much like the 1850s court’s fueling of interstate conflicts around slavery, most notably in its Dred Scott decision. There are important differences, too, but Painter’s work on these eras reminds us of how Americans have found ways to survive the state’s repression and, more generally, that those whom the state seeks to make powerless still have and exercise agency.

One avenue for exercising this agency was (and has remained) flight, as in the Black migrations of the 1870s and 1920s. But Painter’s histories, her art and autobiographies, and her life also offer another view of how to exercise freedom in the face of persecution: by staying, organizing, and collectively seeking to build livable lives. This is the story of Hosea Hudson and the many communists of the South. In the midst of the Great Depression, Hudson and his comrades remained in the South, committed not just to organizing themselves but even to putting their bodies on the line for one another. For Hudson, as for Painter, individuals may exercise freedom, but collectives guarantee its existence.

More from The Nation

What Comes After the Apocalypse? A Q&A With Joshua Oppenheimer What Comes After the Apocalypse? A Q&A With Joshua Oppenheimer

Oppenheimer’s latest film, The End, is a Golden Age, post-apocalyptic musical crying out from the depths of the earth.

The Peculiar Case of Ignatius Donnelly The Peculiar Case of Ignatius Donnelly

The Minnesota politician presents a riddle for historians. He was a beloved populist but also a crackpot conspiracist. Were his politics tainted by his strange beliefs?

The Agony of Aaron Rodgers The Agony of Aaron Rodgers

Is he the world’s most interesting athlete or is he just a washed-up crackpot?

Can You Understand Ireland Through One Family’s Terrible Secret? Can You Understand Ireland Through One Family’s Terrible Secret?

In Missing Persons, Clair Wills's intimate story of institutionalized Irish women and children, shows how a family's history and a nation’s history run in parallel.

Peter Schjeldahl’s Pleasure Principle Peter Schjeldahl’s Pleasure Principle

His art criticism fixated on the narcissism of the entire enterprise. But over six decades, his work proved that a critic could be an artist too.

How the Western Literary Canon Made the World Worse How the Western Literary Canon Made the World Worse

A talk with Dionne Brand about her recent book, Salvage, which looks at how the classic texts of Anglo-American fiction helped abet the crimes of capitalism, colonialism, and more...