The Empty Promise of Megalopolis

The Empty Promise of “Megalopolis”

Francis Ford Coppola’s long-awaited magnum opus is a flop.

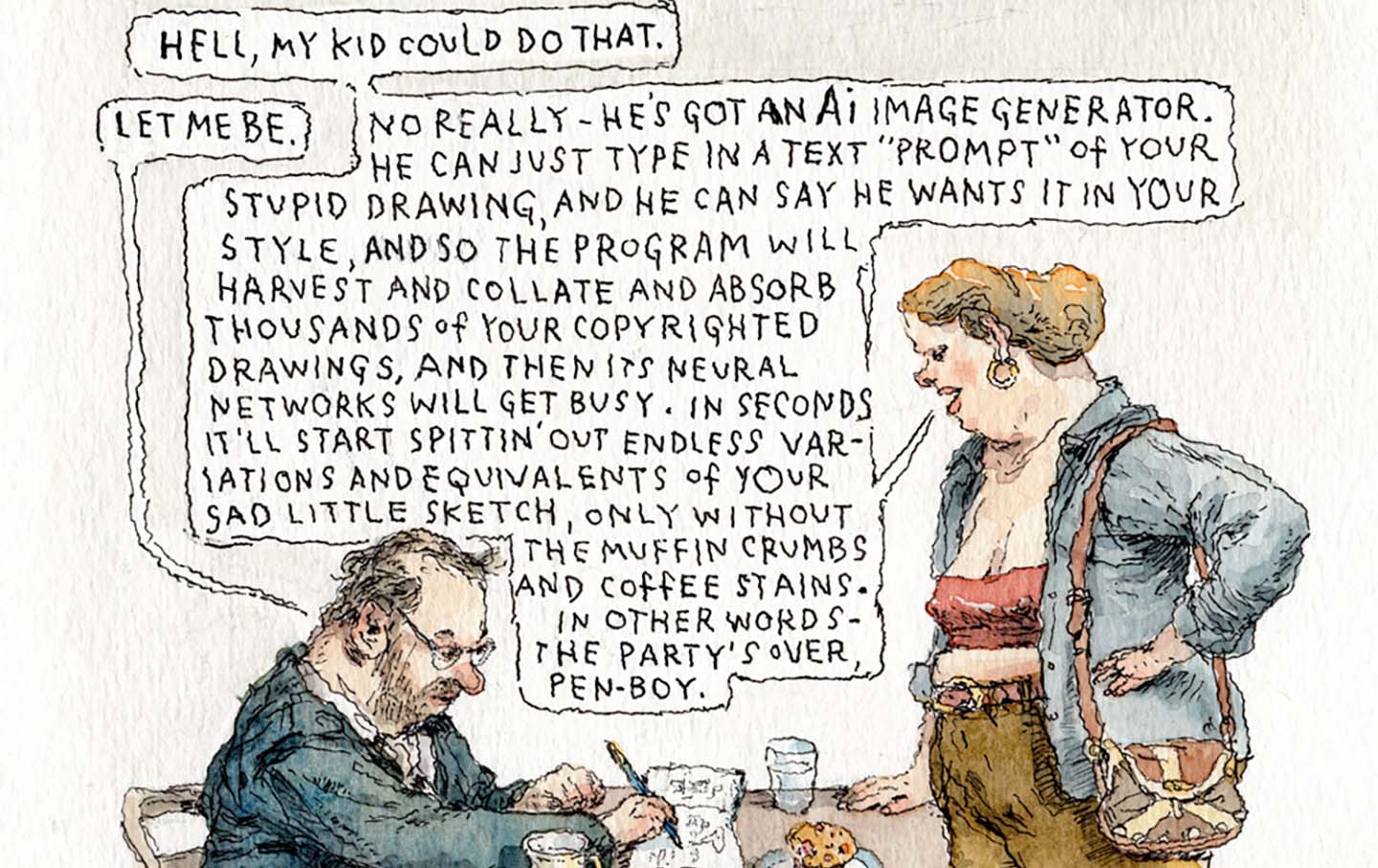

Adam Driver as Cesar Catilina and Laurence Fishburne as Fundi Romaine in Megalopolis.

(Courtesy of Lionsgate)

Francis Ford Coppola’s Megalopolis frets about the future. The star-studded sci-fi drama pits the ambitious and superpowered architect Cesar Catilina (Adam Driver) against the corrupt Mayor Franklyn Cicero (Giancarlo Esposito). At stake in this modern-day fable is their shared home of New Rome, a retrofuturist, art-deco rendering of New York City and a proxy for an America in a state of decline.

Written, directed, and financed by Coppola, Megalopolis has been in development since the 1980s and arrives after a long series of production woes, revisions, and lawsuits. This difficult path to completion, reminiscent of his 1979 Vietnam War epic Apocalypse Now, has become part of the film’s marketing. In interviews, Coppola has pitched it as his magnum opus, and ads have played up past instances when his maximal filmmaking pushed the art forward. (“One filmmaker has always been ahead of his time,” asserts one trailer.)

But the film doesn’t live up to all this hype and star power. Despite Coppola’s avant-garde ambitions, Megalopolis is at heart a familiar tale of a great man single-handedly fixing an ailing world, and the director does not embellish or complicate this boilerplate comic-book plotline. The film is one of the biggest and dullest cinematic whiffs of the year.

Structured somewhat like a Greek play, Megalopolis is sectioned into titled scenes that establish the various milieus and players of New Rome, most of whom are wealthy. Cesar’s driver and assistant, Fundi Romaine (Laurence Fishburne), serves as the Greek chorus, narrating the decadent exploits of New Rome’s bankers, socialites, politicians, and media members. The plot centers on Cesar and his Robert Moses–like mission to build a better and more egalitarian New Rome—Megalopolis, a city that will serve its residents rather than exploit them. This ambition threatens the decadent and plutocratic social order that Cicero is content to maintain.

Cesar and Cicero are written as opposites, but their differences are minimal: While the mayor hobnobs with the rich, leads parades, and plans the construction of a casino, the architect spends most of his time brooding in black clothing, drinking booze, and quoting Shakespeare and Ralph Waldo Emerson. They are both aristocrats.

Cesar, however, has a superpower: the ability to stop time. He’s not quite a hero, though. In an early scene, he uses this ability to pester the public rather than serve it. As the head of an opaque city agency called the Design Authority, he can determine demolitions and construction. But when the agency knocks down a skyscraper, Cesar ignores the protests of affected residents, stopping time to look closely at the collapse of the building. His ability, the moment suggests, is a kind of enhanced vision: He can see what others cannot.

This doesn’t win him much support, but Cesar will save the city, Coppola insists. Why? Because he has invented Megalon, a kind of magical liquid metal that can take any shape and that will be the building block for Megalopolis. Cesar is no tyrant like Cicero; he’s simply a misunderstood genius. He’s also a proxy for the filmmaker, who seems eager to justify the long ordeal of erecting his own behemoth.

After seeing Cesar stop time early in the film, Julia Cicero (Nathalie Emmanuel), the mayor’s bright but unfocused daughter, asks to work for him. She soon becomes his assistant and later his lover, roles that deepen Cesar’s rivalry with her father. The character is underwritten, but Emmanuel’s performance is the most charming of the film; she plays Julia as a bright-eyed idealist.

As Cesar and Cicero tussle over Julia and the fate of New Rome, other characters hatch their own schemes. We get Clodio Pulcher (Shia LaBeouf), Cesar’s jealous and depraved cousin, who resents the architect and embarks on a pseudo-populist campaign to discredit him. We also get tabloid journalist Wow Platinum (Aubrey Plaza), Cesar’s ex-lover, who marries his uncle, the banker Hamilton Crassus III (Jon Voight), so she can inherit his fortune.

Coppola tries to wrest comedy and dramatic tension from these harebrained plots, but the storylines just crowd the frame. And then, as all this is going on, a decaying Soviet satellite starts hurtling its way toward New Rome.

This madcap mix of fantasy, romance, and palace intrigue might work if there were real conflict in the story or chemistry between the actors, but New Rome has no material or spiritual foundation. It is built entirely from allusions, allegories, and symbolism, undermining the film’s attempts at social commentary. The working poor that we glimpse at the margins of the story have no actual lives or culture. They are portrayed as faceless, dingy crowds who make no specific demands and play no role in the making of their own lives.

New Rome’s elite may occupy lush penthouses and wear sumptuous clothing, but their world is also merely gestural. We see their fortune, but we don’t know where it came from or how they feel about it. Coppola tries to paper over this emptiness with fantastical visual flourishes, such as Cesar turning time into slow-motion tableaux and injustice being represented by a statue of Lady Justice collapsing into the street, but such moves bring to mind the cheap effects from a music video.

Fritz Lang’s silent classic Metropolis, Joseph Mankiewicz’s Shakespearean Roman epic Julius Caesar, classic Hollywood musicals like The Wizard of Oz, and film noir all come to mind when watching Megalopolis. But the film never harnesses all of this friction; nothing really happens in its stilted and overstuffed scenes. The actors bumble about independently, swinging from ham to gravitas to operatic bloviating. Major plot points get resolved without any action from the main characters. Fundi Romaine’s droning narration explains the obvious. Megalopolis more often feels like a slideshow than a story.

And beneath all the staid spectacle is the banal idea that social change can only come about through the will of daring strongmen. This Ayn Rand–inspired argument is questionable in most circumstances, but here it’s especially jarring because Cesar never articulates or shows what Megalopolis will offer to the average citizen. In the film’s triumphant finale, the magical city’s primary innovation appears to be moving sidewalks, a nifty feature that finally wins over Mayor Cicero. That’s it? The future of cities, of America, of humanity, is something you’d find at an airport?

Coppola’s pedigree can’t obscure the fact that his film is thinking no harder than the average bloated blockbuster. “We’re in need of a great debate about the future,” Cesar asserts in one of the final scenes. I agree, but Megapolis, which is likely Coppola’s last film, doesn’t even speak to the problems of the present.