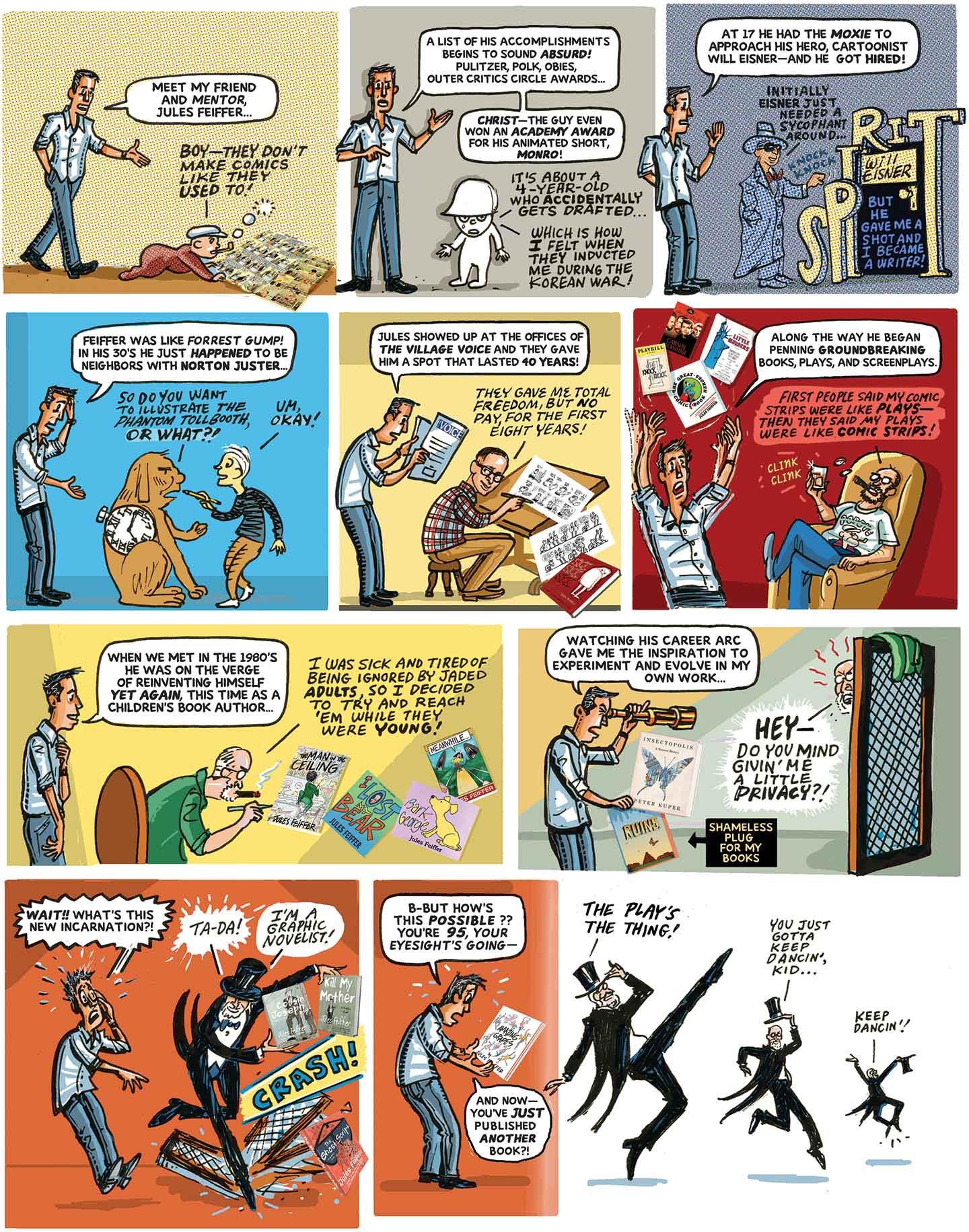

A Dance to Jules Feiffer at 95

Cartoonist and writer Jules Feiffer is a national treasure. To mark his 95th birthday, we had some questions for the longtime Nation contributor.

Peter Kuper: You said you learned when you were young that every time you stuck your neck out, you’d get clobbered. Yet you became a political cartoonist, and the job description is… you stick your neck out—along with your finger—and poke everything and everybody in the eye. So what motivated you to become a political cartoonist?

Jules Feiffer: I didn’t set out to be a political cartoonist, but when I started work in 1956, it was after two years in the Army. It was the height of the Korean War. It was just post–Joe McCarthy. The entire thinking class—or the young thinking class that I knew around my age group—were very cautious about ever expressing their opinions one way or another. People were afraid of getting into trouble or saying out loud what they really thought. And what I really thought was: “What kind of bullshit is this, and what can I do about it?” And so, with the cartoon I had just begun in The Village Voice, with no particular thoughts of how I was going to proceed, I was already set on a political track. Because I had already written the story “Munro,” about a 4-year-old who gets drafted into the Army by mistake, and he can’t convince anybody he’s 4. So it was clear that I was going to deal with authority.

Kuper: When you were younger, though, did you have the philosophy that you should push back against authority, in school or with your parents?

Feiffer: Well, when I was young, it didn’t much matter what I thought, because I was scared of my shadow, and I wouldn’t have done anything about anything.

Kuper: Which brings me back to my question. You came from that, and then you end up in a profession that is the most extreme example of shaking the cage.

Feiffer: Well, because shaking the cage is what I found myself drifting into doing, and finding I had no choice but to do that because I was living in a country that scared the shit out of me in terms of the direction it was going. And if you ask me how I changed the country, well, today I find myself living in a country where I’m scared shitless because of the direction in which we’re going.

Kuper: In many ways, you seem like the character in the Woody Allen film Zelig. You were present at important points in history—but unlike Zelig, you participated. You were on the trial defending Lenny Bruce. You crossed paths with Martin Luther King Jr., became friends with James Baldwin and Harry Belafonte. You were in Chicago during the 1968 Democratic National Convention riots, etc. There are dozens of examples of this.

Feiffer: And I was there because I fucking wanted to change everything, and I was trying to figure out how best to do that. So many of the conversations I had with some of the people, particularly Black and brown people, I knew at that time were: “What’s next? What do we do?” And it wasn’t as if we ever helped each other learn anything in particular. But we gave each other a sense of support that we certainly needed, because we felt very much in a minority, and very much in the right.

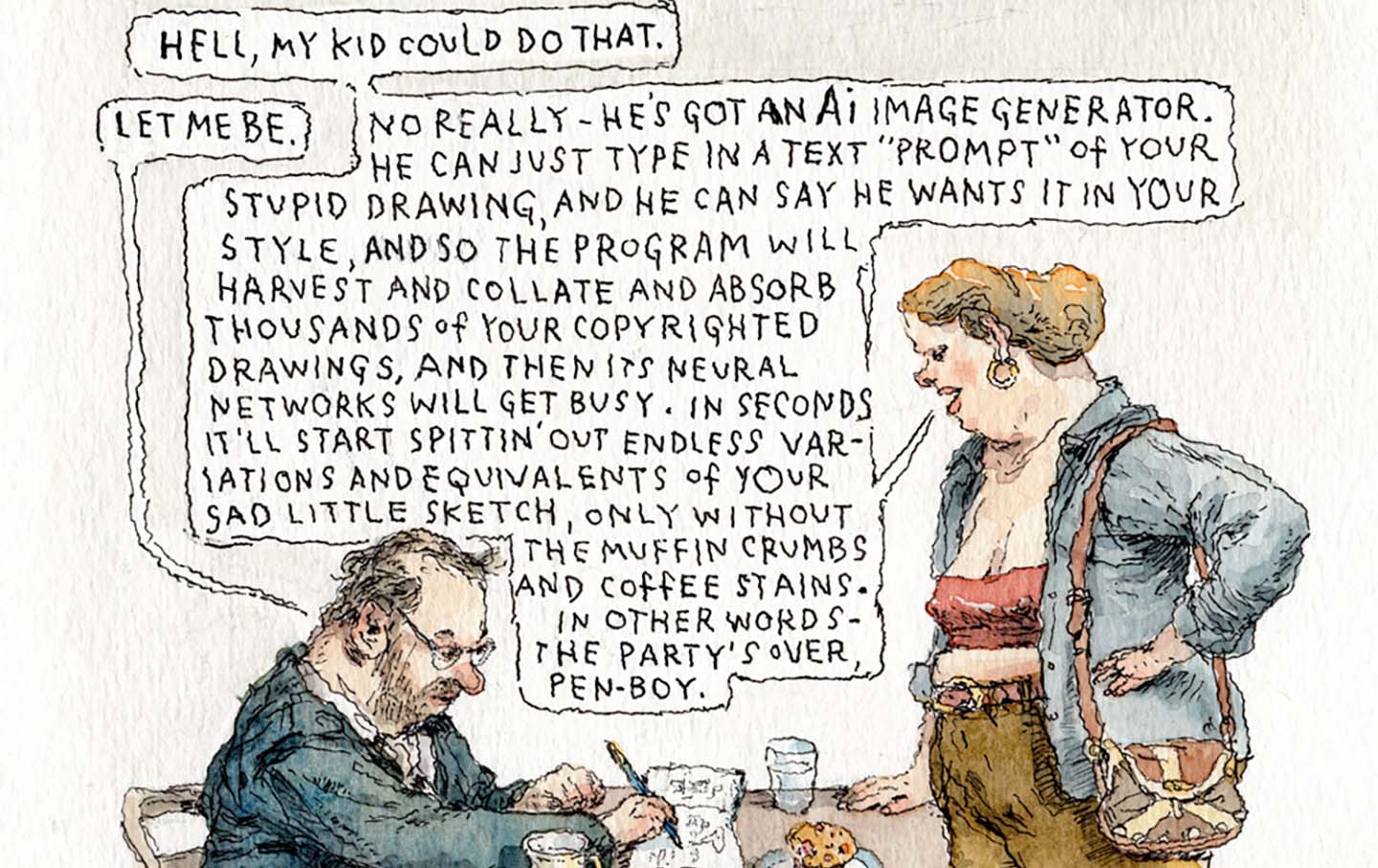

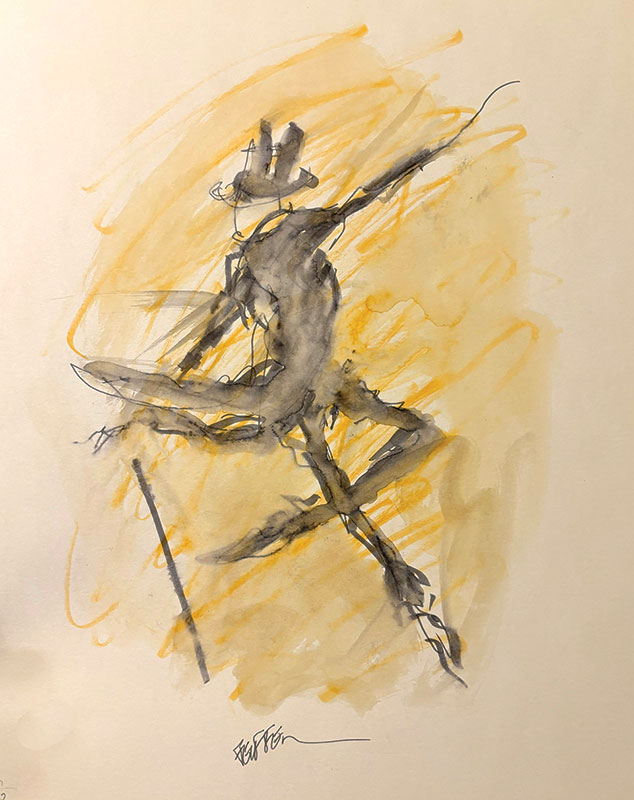

Kuper: Given your macular degeneration, what do you see when you draw nowadays? When you put pen to paper, can you see the line clearly and the words you’re writing on the page?

Feiffer: The illusion is that I see as good as I’ve ever seen, which is not true, but it’s the illusion. And I proceed with each drawing from page to page with complete confidence that it will turn out exactly as I want, which is not always the case. Failure is a big part of my process. And the title of my next book is My License to Fail. That’s an important recognition and an important statement: that in order to succeed, I have to be ready to fail at everything. And it took me years to do this, not as a judgment but as a process. I think I’ve just found a different way and a new way, within the confines of the limits of age and my loss of vision, to say some very strong and powerful things and say them in different ways that will move people in ways that they haven’t been moved by my work before. That’s my illusion, and I’m gonna stick to it.

Kuper: You’ve managed to keep working despite things not changing much in society—or sometimes getting worse. Has there still been a glimmer of optimism in the process?

Feiffer: I think there used to be, certainly when I was younger, more optimism than there is now. But I can’t say that I’m a pessimist now. I think it’s an endless fight, and it goes on. Endless fights go on endlessly.