Joan Baez Looks Back

I Am a Noise, a career-spanning documentary, makes it clear that the folk singer was one of the most important political musicians of her generation.

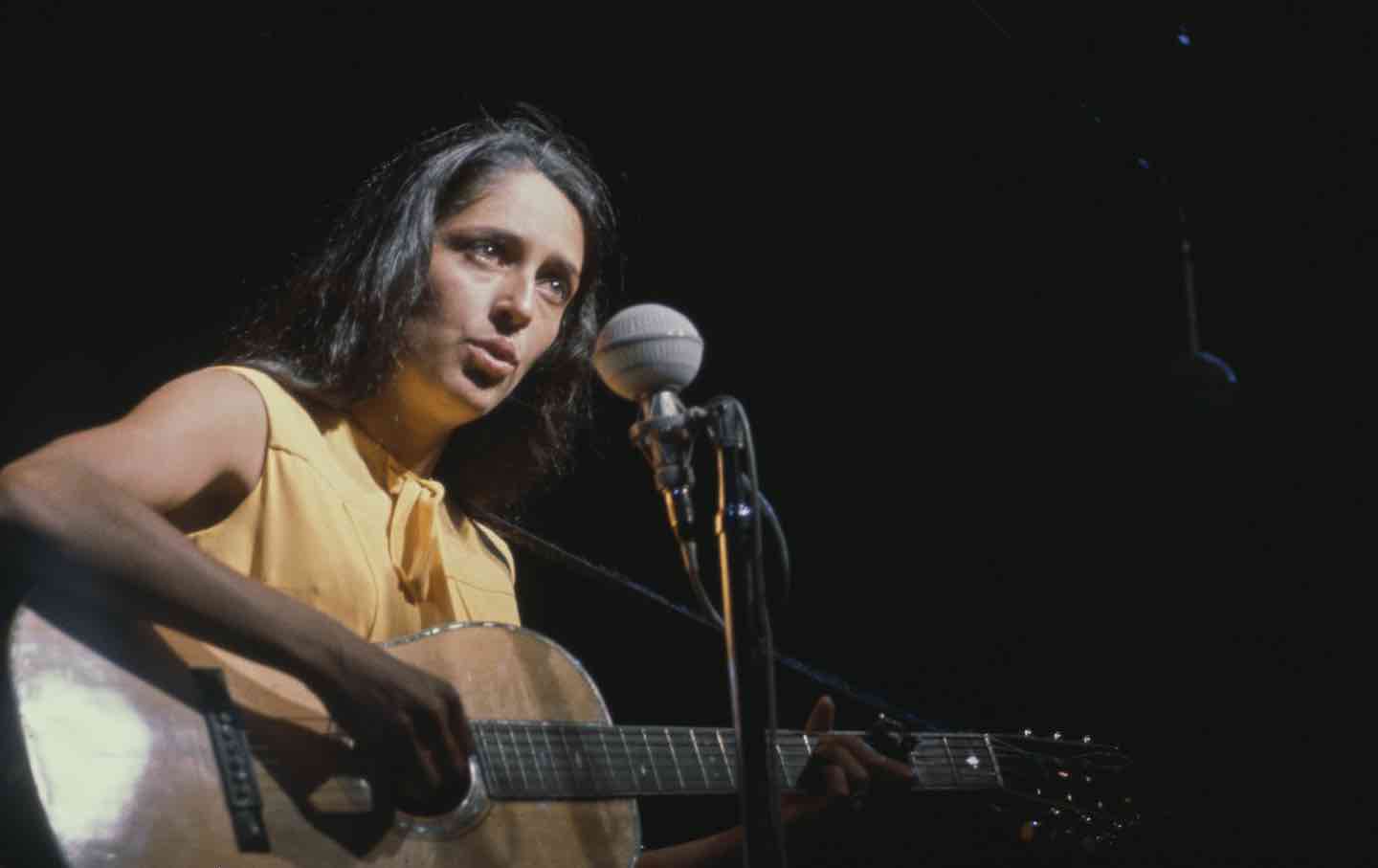

Joan Baez at the Newport Folk Festival, 1964.

(Photo by Gai Terrell / Redferns / Getty Images)Joan Baez’s voice—commanding, clear, and accessible—was a soundtrack to my childhood and, by extension, that of so many other people in my generation (the children of the baby boomers). When my aunt handed me Any Day Now, Baez’s album of Bob Dylan covers from 1968 (recorded while the two weren’t on speaking terms), I could feel in its notes the heartache of their fractured relationship, not to mention a fractured decade, a fractured country. Baez’s voice draws cries for justice from Dylan’s opaque lyrics in songs like “Tears of Rage” and “I Shall Be Released.” In a way, the album is the setting of a debate, arguing her side of their big split on whether an artist should be committed to the realm of politics or the realm of pure art. Her vote: Do both.

Baez was still a presence in the folk and rock scene of the 1990s when I was discovering her work, busy mentoring and collaborating with the feminist folkies of my day: Dar Williams, the Indigo Girls. Like those artists, Baez has earned some (sexist) derision—her unsullied politics, her lack of edgy experimentation. Some years ago, in an interview commemorating Woodstock, she chastised herself for being too “priggish” by asking the mud-frolicking hippies to sit down and then giving a rambling lecture about her husband David’s arrest for opposing the war. “Nobody was really thinking about the serious issues,” Baez said. “I was graceless enough not to just accept it.” But she later called the reporter back just to reiterate why Woodstock did not qualify as a real revolution: “Social change doesn’t happen without the willingness to take risks.”

Baez’s music has not only soundtracked my life and those of my peers; it’s also been the music of worldwide protest, the anthems of dissent. She is famous at home for playing songs at the 1963 March on Washington and other civil rights rallies, and for a lifelong commitment to the American anti-war movement and the prison reform movement. Abroad, she has shown up in places where there was revolution or strife: most famously Hanoi, but also war-torn Sarajavo, Israel and Palestine during the First Intifada, at a memorable concert in the the Czech Republic during the Velvet Revolution (Vaclav Havel carried her guitar), and beyond. “Nonviolent action was what I was born for,” she says in Joan Baez: I Am a Noise, a new documentary that chronicles the way her public struggle for justice has been matched—and sometimes overshadowed—by an inner struggle for peace and self-awareness.

Despite her ex Dylan once singing that “she’s got everything she needs, she’s an artist, she don’t look back,” Baez has been taking a candid look back for years, releasing two memoirs and becoming the subject of a number of documentaries, including an episode of American Masters on PBS in 2009 that looked at the 50th anniversary of her first appearance at the Newport Folk Festival, as well as her work in the studio.

I Am a Noise is an attempt at a definitive, intimate coda to this period of reflection. The film, by a trio of directors—Miri Navasky, Karen O’Connor, and Maeve O’Boyle— spotlights the singer’s musings on her relationships, music, family secrets, mental health struggles, and a long career of left-wing agitation. As the film makes clear, Baez was right that one did not need to choose between politics and art.

She was merely “the right voice at the right time,” Baez says of herself—a young protest singer who graced the cover of Time magazine in 1962 at the age of 21. But throughout the film, such self-effacing quips are undercut by archival footage that highlight Baez’s charisma and fervor. I Am a Noise is split between two modes, moving back and forth from her 2018 “Fare Thee Well” tour, which was her last, to a biographical portrait that shows her engaged in deep reflection. In both modes, the film offers stunning moments, first by showing us how Baez literally walked through history, marching next to James Baldwin in Selma, offering tense smiles despite the threat of violence. And in the reflective mode, she sits at her kitchen table, admitting that “Dylan broke my heart” and laughing ruefully.

In I Am a Noise, Baez admits that she’s still haunted by the racist taunts she heard as a young student (her father was Mexican), and her sister details the conflicts caused by their father’s resentment (he was also a scientist of some renown) when Joan’s music started bringing in real money. One of the more poignant scenes shows Baez returning to Alabama on her final tour and being greeted tearfully by Black elders who remembered her courage. And one of the funniest scenes documents a young Baez imitating a baby-faced Dylan’s rough voice to raucous laughs, in that brief shining moment when she was more famous than he. Poignantly, in 2018, we see her warming up after not singing for weeks (with a Dylan tune, of course), her voice cracking.

Yet even if the audience wants the camera to linger on many of these moments, especially the musical performances, the film has another agenda. It assumes that we know Baez’s basic story and catalog, as well as the gist of the causes she embraced. Filmmakers and subject have chosen an internal focus here, attempting to excavate Baez’s anxieties over the decades.

To do this work, the directors tap into a treasure trove of resources provided by Baez herself: audiotapes recorded by the artist and her family, including her sister Mimi Fariña, in therapy sessions, as well as tapes they sent back and forth to one another. We are even privy to the guided meditations Baez listens to to calm herself. I Am a Noise also re-creates, with animated interludes, Baez’s letters and drawings, lingering on sentences expressing despair in every phase of her life, contrasted by her hope that the world might live up to her vision. “Nothing makes sense to me but you me and the revolution” is a line she penned to her husband David Harris, who was jailed for burning his draft card. The pair split up eventually, with Baez joking in voice-over that she is a perennial failure at one-on-one relationships and only successful in creating intimacy with a crowd—one-on-thousands. That sense of personal failure pervades the film: alienation, panic, depression, and being “a mess,” by Baez’s admission.

More unexpected than the archival material or the concert footage is the film’s exploration of Baez’s doubts, her gentle probing into her own protest-hopping mindset. Baez tells us without shame that she was addicted to activism and even felt “lost” when the war in Vietnam ended. This voice-over is juxtaposed with scenes of her younger self, furious, telling a reporter that the United States should “stop bombing children!” Her vanity and private anguish might have been motivators, but that didn’t make her wrong. None of her observations makes her public compassion—as a young teen, she wrote that she wanted to be “like Gandhi”—less remarkable. It just helps us get her, and to understand that the unshakable activist with firm convictions, the commanding singer getting the hippies to sit down, was also an insecure, troubled young woman. Many narratives about a person exist at once.

And in this case, many narratives about a family exist at once. For as we learn about the episodes of depression that afflicted Baez at various stages of her life, her stumbles at relationships and in developing a concrete sense of self, her troubles relating to her sisters, and even her claim that she has multiple personalities, there’s a continual hint that something was seriously amiss at home, early in life. The final 40 minutes of I Am a Noise slowly open the door to the revelation that Joan and her sister Mimi Fariña both went to “recovered memory therapy” and say they discovered repressed memories of sexual abuse on the part of their father, Albert.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →In many cases, this kind of therapy has been controversial, even discredited.The filmmakers seem to understand that this is tricky ground, and Baez seems to as well. So the recovered memories are presented in the film as both an illuminating answer and a nonanswer (Baez firmly believes that both her parents, now dead, had repressed the memories, too). One thing is clear: Whether or not we believe we’ve just unlocked the key to Baez’s lifelong angst, the process of that unlocking has led to some measure of peace for her.

As the film delves into Baez’s mental illness—she describes the multiple personalities, some embodied as animals, that live inside her, a fragmentation that she believes arose from that early abuse—I recalled Joan Didion’s words in “Where the Kissing Never Stops,” an essay that seems less critical of Baez now when revisited in tandem with this film. “Joan Baez was a personality before she was entirely a person,” Didion wrote, “and, like anyone to whom that happens, she is in a sense the hapless victim of what others have seen in her, written about her, wanted her to be and not to be.” In this case, we see Baez as not just an avatar of the protest movement but another American star damaged by early fame, on a continuum with figures as disparate as Judy Garland and Britney Spears.

By dwelling on the long-term psychic turmoil of such a luminous public figure, the filmmakers are adding a new dimension to what we think we know about the 1960s, which makes it an interesting companion to recent films like Summer of Soul by Questlove and The Velvet Underground by Todd Haynes (even the new Beatles documentary by Peter Jackson rewrites the band’s breakup). These films have expanded how we should view the counterculture, painting a multifaceted picture that is far from a monolith of white, straight, carefree hippies. Baez’s story reminds us that the marriage between the movement and the counterculture was rocky. A lot of hippies didn’t want to hear about the Vietnam War. And some people who devoted their lives to ending the war felt lost when it was over.

Baez’s endurance and quest for self-enlightenment, as chronicled in this film, are a most unusual window into a public figure’s deepest thoughts and fears. We will never really know what primal angst or ambition animates Bob Dylan, for instance; once again, Baez is more generous than her peers. Maybe it’s that generosity that has helped her find some grace and time to heal. Joan Baez: I Am a Noise ends with her dancing alone in the fields at her California home. But she’s not alone. The camera is on her.

Take a stand against Trump and support The Nation!

In this moment of crisis, we need a unified, progressive opposition to Donald Trump.

We’re starting to see one take shape in the streets and at ballot boxes across the country: from New York City mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani’s campaign focused on affordability, to communities protecting their neighbors from ICE, to the senators opposing arms shipments to Israel.

The Democratic Party has an urgent choice to make: Will it embrace a politics that is principled and popular, or will it continue to insist on losing elections with the out-of-touch elites and consultants that got us here?

At The Nation, we know which side we’re on. Every day, we make the case for a more democratic and equal world by championing progressive leaders, lifting up movements fighting for justice, and exposing the oligarchs and corporations profiting at the expense of us all. Our independent journalism informs and empowers progressives across the country and helps bring this politics to new readers ready to join the fight.

We need your help to continue this work. Will you donate to support The Nation’s independent journalism? Every contribution goes to our award-winning reporting, analysis, and commentary.

Thank you for helping us take on Trump and build the just society we know is possible.

Sincerely,

Bhaskar Sunkara

President, The Nation