Lately, figurative painting has become a much stronger presence on the art scene—and in the art market—than it’s been in living memory. About a decade ago, the hot thing was a certain kind of post-minimal but decorator-friendly abstraction, usually exemplifying what John Yau called, at the time, a “well-produced scruffiness” via “ironic variations of the artistic canon,” as exemplified by such honored precursors as Agnes Martin, Robert Ryman, and Frank Stella. Critics got all bent out of shape over the market frenzy over a few of these young neotraditional abstractionists, for instance Jacob Kassay and Lucien Smith, and their fate was sealed when Walter Robinson coined the term “zombie formalism” to describe the formulaic nature of their production and its indebtedness to the color field and minimalist painting of the 1960s. No one could ever take that cohort seriously again, and collectors started looking elsewhere for new finds. Figurative painting seemed like a fresher field. The push in that direction has only taken on greater momentum, partly because figurative painting seemed to offer artists a way to communicate more directly their passionate beliefs, and to focus on human stories rather than on abstruse aesthetic concerns. And it offered curators and collectors a way to display their sympathies right there on the wall—like wearing one’s heart on one’s sleeve.

But even more than with the earlier clamor over abstraction, the rush to embrace new figurative painting has led to some undesirable consequences: Artists who couldn’t paint their way out of a paper bag are being exhibited cheek by jowl with refined stylists whose images evince a profound engagement with contemporary reality. Often enough, the former seem more numerous; various undead forms of figure painting roam the galleries and museums today just as the revenant styles of abstraction did a decade ago. The indiscriminate uptake of the new figurative painting suggests it might have as brief a heyday as the formalism of a decade prior. That’s all the more reason, though, to look for the artists whose figuration is built to last—several of whom exhibited their work in New York this past fall.

At just 29, the American-born, London-based Issy Wood is one of the most interesting figurative painters who have emerged in some time, and all the more intriguing because she avoids the zombie-like condition of so much of the art around her precisely through her paradoxical invocation of a dead or dying sensibility—and her deadpan, almost academic way of rendering it. She dissects the human figure into detached parts, and likes to substitute artificial images of the body for direct depictions of it. The objects she paints, mostly in shades of gray, inevitably have a baleful, cadaverous aspect. Her recent show, “Time Sensitive,” which was on view at Michael Werner, was her second solo in New York. Her first, in early 2020, just before Covid, was in retrospect all too timely, evoking for me, at the time, a free-floating anxiety about the ominous state of things, a sense of impending doom. As impressive as that show was, the paintings she’s made since then—“Time Sensitive” includes 18, all dated 2021 or 2022—are even stronger. Partly that’s to do with how beautifully the paintings’ surfaces are knit together; Wood has perfected a way of painting that is neither crisp and linear nor conventionally painterly either. Rather, her subtly tactile surfaces—you almost seem to feel the images being dabbed, point by point, into visibility—give the paintings a physical immediacy even as they put her subject matter at a remove. Looking at these paintings, I kept feeling as if I were catching scenes from a film noir through the fuzzy consciousness of someone not entirely awake. Detail is not lacking, but it’s enveloped in a slight haze. Things seem neutral, distant, dissociated, but with an inexplicable air of mystery that’s absorbing.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

In an interview with curator Sarah McCrory, Wood explained that her parents are physicians, who gave her an early awareness of “a visual vernacular to medical and pharmaceutical design, a kind of mixture of the practical and the gruesome as well as the very emotionally uninvolved.” One thinks of the Belgian artist Luc Tuymans, who has often borrowed his imagery from medical books, and with whose work Woods has much in common; in 1992, he gave a series of paintings the telling title, “Der Diagnostische Blick”—the diagnostic gaze.

Like Tuymans, Wood cultivates a cool, detached style, tonally muffled and chromatically understated. Her subjects typically fill the frame, as if being examined in extreme close-up; the choices are odd, sometimes almost inexplicably surreal: a cow’s udder, the seat of a car, a toy rabbit—things that become odd just through being closely observed, like a word that turns into nonsense by being repeated. People appear only as isolated fragments—a hand on a door knob, a finger pulling lips back to show teeth and gums—while inanimate things stand in for people: An armor helmet is offered as a self-portrait, titled Me at the season finale, 2022; what looks at first like the back of a woman’s neck must in fact represent that of a mannequin, judging by the hole that seems to have been gouged into it.

In her introduction to the catalogue for “Time Sensitive,” writer-curator Margaret Kross suggests, “Wood’s paintings reflect the subject of a cis-female who desires an escape from her socially-prescribed role.” Maybe, but there also seems to be a broader, free-floating sense of alienation at work in her paintings. The hand on the door knob in Closing, 2022, for instance, belongs to a man, not a woman. The composition resembles a close-up from some Hitchcock thriller—the very fact that we can’t know what’s on the other side of the door is what creates the suspense. This is not the hand of power but of fear. And as for society? It’s out of the frame, so who knows whether our destiny is prescribed by it, or by some unknown disaster all one’s own? But Wood’s alienation is so finely tuned that her disquieting feelings become strangely seductive.

Ifirst encountered Christina Quarles’s paintings on the small screen of my smartphone. Back in early 2020, when Covid had closed the galleries and museums, and I was only able to see art online, I realized I had to face the question of what exactly I was seeing when I was seeing paintings as digital images. So I wrote about artists whose work I’d never seen in person but knew primarily through Instagram, Quarles among them. What I came to understand was the seeming paradox that if a painting looked undeniably strong and eye-catching on Instagram, it might not actually be that good in reality; the best sign of a good painting online is that its image generates some dissatisfaction with the limitations of the digital. Quarles was one of those artists whose work succeeded in making me conscious of the limitations of what I was seeing online.

What happened after that surprised me. Quarles became an art market darling, her art a plaything for speculators. Last May, a 2019 painting of hers, at auction with an already eye-watering estimate of $600,000–$800,000, sold for $3.7 million—that’s $4,527,000, with the so-called “buyer’s premium.” Rightly or wrongly, just like Instagram, the art market affects how I see a work. A painting that looks good when it’s by a promising up-and-comer looks different when it’s purported to have the same value as a rare work by an acknowledged master of the past. Is that unfair? Only if you think we ought to be able to perceive the present with the same sagacious eye we cast on a history whose outcome is already known. Just like the critics who’d disparaged zombie abstraction when they saw some young painters be overvalued, I let the market hype over Quarles affect how I saw her work. And remember, I had still never seen a painting of hers in the flesh. But in light of the market, the works I kept seeing in magazines and online lost their allure—I started to find mostly flaws and affectations in them. The strange way she has of warping, breaking apart, and reconstructing her figures (or rather, fragments of figures), for instance, which had at first seemed intriguingly eccentric and uneasy, started to look almost the opposite—like a stylistic formula for keeping everything tightly framed inside the rectangle of the canvas. Likewise the way her paintings deconstruct, distort, and recombine bodies came to look strangely cold and distant, drained of emotional involvement. Maybe this was zombie figuration after all.

Last fall gave me my first opportunity to see Quarles’s paintings in person, in a solo show titled “In 24 Days tha Sun’ll Set at 7pm” at the Chelsea outpost of Hauser and Wirth. I went expecting to be confirmed in my newfound reservations about her work, but I was in for another surprise. Finally able to see Quarles’s work in person, I had to admit that the evidence was clear: The suspicions I’d developed based on my readings of online images, but inflected by her wild market success, turned out to be misguided. Quarles’s paintings are brilliant and powerful. They might best be thought of as abstract paintings constructed out of mismatched representational elements, works in which one witnesses something happening that stymies one’s impulse to narrate it.

Quarles uses geometrical elements in her work to suggest contingent or transient architectures—walls, ground planes, and skies reconceived as theatrical stage sets rather than as natural realities—that place her protagonists in airless, claustrophobic spaces that we viewers, nonetheless, can contemplate from the outside. Take, for example, Same Shit, Diff’rent Day, 2022. The closest thing in this horizontal composition to a coherently legible figure is the one kneeling on the left; but its legs are merely more or less leg-shaped, disembodied color stains, and it somehow has three pairs of hands. Cradled in its hands is the featureless head of another, even more elusive ghost of a figure, which seems to be tumbling over a sheet of plywood leaning over, one of three planes that provide a simple geometric grounding to the images—but that figure is mostly a sort of blank phantom. Meanwhile, a third figure to the right holds a sort of downward-facing dog position, but its body and limbs are an indistinguishable mix of bulbous forms. Quarles’s figures are Frankenstein monsters built out of ill-assorted fragments. That’s not only true of what’s depicted but also of how these creatures are depicted.

She engineers surprising juxtapositions between passages that are painted with long, sinuous brushstrokes, others that are executed by staining the canvas, and others still that are mechanically mediated—if I understand it correctly, these are worked out on a computer and then printed out as stencils that are then hand-painted, though they end up looking deceptively as if they were collaged onto the canvas. The clash among these diverse ways of using paint turns out, in her hands, to be exciting in itself. Quarles explained in a recent interview with Lee Ann Norman in The Brooklyn Rail that she sketches these backgrounds using Adobe Illustrator and one of the things that makes these paintings so striking is how they openly set up a clash between the physical, corporeal realm and the world as seen through digital mediation—the tension between the handmade parts of the canvas and those passages constructed on a computer. Even without knowing much about the precise process, we can immediately see that that Quarles’s work is composed of two distinct materialities, and their juxtaposition sharpens our perception of each. In the interview, Quarles talks about this process as reflecting a “psychic divide,” which seems true enough, but for the viewer, it presents a perceptual divide too, a distinction between two different ways of experiencing an image, which becomes part of the work’s subject. For Quarles, this divide seems to register her divided identity as someone who had a Black and a white parent—“how you internalize your own sense of self is met with resistance from everybody else”—but even those of us who have not had to experience that particular conflict can understand these paintings in which the self is fractured both in itself and in relation to its environment.

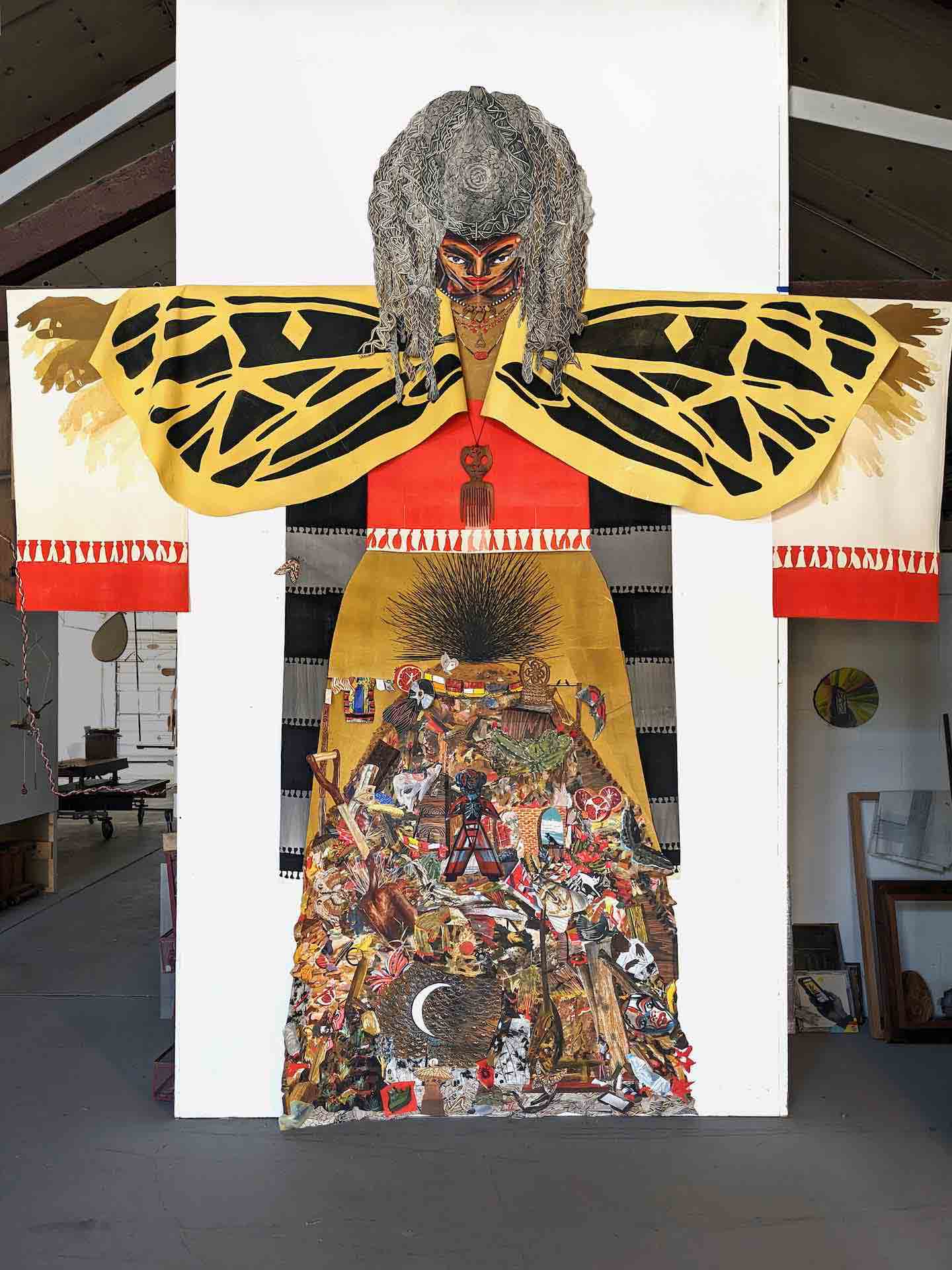

While Quarles has enjoyed the art world spotlight, Paula Wilson has been flying under the radar. Maybe one reason is that she lives and works in Carrizozo, N.M. (pop. 942), rather than New York or Los Angeles or her hometown of Chicago. Her first New York show, back in 2008, made a big impression on me with its youthful energy, its material and chromatic richness, and its conceptual density. Over a decade later, in what is still only her third one-person show in Manhattan, Wilson’s early promise is fulfilled. The show, which was on view at Denny Dimin Gallery, is called “Imago”—the word is Latin, of course, for “image,” but the word has taken on a couple of more specialized meanings. In entomology, it refers to the fully mature state of a winged insect, after it’s undergone metamorphosis. In psychoanalytic terms, it represents an unconscious mental image, perhaps based on a parent, that influences a person’s present behavior. All this suggests that if Wilson, now in her mid-40s, is self-consciously reflecting on her own achieved maturity (as an artist, as a person), she is doing so in full awareness of all its ambiguity.

Luckily, however, while Wilson has continued to develop a mastery of any number of distinct conventions and techniques—the current show encompassing printmaking, collage, painting, sculpture, and video—she handles them with a freedom that underlines a decidedly unconventional mind. One’s first view of the show is dramatic: On the wall facing the gallery door, reaching nearly to the ceiling, is a 13-foot-high assemblage, of acrylic and oil paints alongside wooden and beaded jewelry made in collaboration with Mike Lagg, depicting a towering hieratic figure, titled Earth Angel, 2022, with outspread arms garbed in a vast pair of butterfly wings. She bows her head to gaze down knowingly at the crowded world over which she presides, all gathered under her skirts, like the Madonna of Mercy in Medieval and Renaissance art. But unlike the Roman Catholic icon, Wilson’s colorfully winged earth mother shelters not only humanity but more or less everything, a sort of fecund chaos in which the human image plays a small part, and then only indirectly—in the representation of a face as a mask. But these are far outnumbered by other living beings, animal or vegetable (a moth or some oranges), as well as inanimate things, natural or manufactured—tools like shovels, for example, feature prominently. Is this Earth Angel observing the world we are destroying—the mass of images under her skirts might recall the choking debris left behind by a terrible flood—or simply the glut of stuff our world contains before one has imposed a conceptual order on it? Wilson generously allows for both possibilities.

The immensity of Earth Angel is complemented by the intimate scale of many of the other pieces on view—even miniaturized, in the case of an intricate dollhouse-like model of Wilson’s studio, Microhouse, 2022, another work made in collaboration with Mike Lagg, who is the artist’s partner. Much of the work amounts to a meditation on everyday domesticity in a life lived among other species, plants, and, in particular, insects—moths crop up a lot here. I was a bit puzzled at first at the fact that, despite the ubiquity of nature in Wilson’s imagination, the human image, almost any time it appears in these works, is never a “natural” one but always seen through a stylized cultural form—for instance, from African sculpture or the aforementioned Catholic iconography. Particularly striking is Reflected, 2020, a painting made using multiple forms of printing, which, perhaps significantly, derive from different eras and cultures: woodblock, which goes back to Tang Dynasty China; lithography, invented in late-18th-century Germany; and digital, which has existed for just a few decades. The painting’s foreground is occupied by a wooden table with a few scattered objects on it—to the left, some colorful ceramic vessels, a pen and sheet of paper, an aloe leaf, and so on; to the left, a cell phone. Again, one thinks of the coexistence in the present of technologies from various eras. On the white wall behind hang a small landscape painting and a mirror, both framed in the same dark, coarse-grained wood as the table, and also a hook (whose base is, again, the same wood) from which hangs a carved wooden comb, similar in appearance to one that can be seen in Earth Angel. Reflected in the mirror is a naked, brown-skinned woman, one hand posed on her hip, the other more demurely covering her sex. Her face resembles a mask, a piece of traditional African carving. One wants to read this as a kind of indirect self-portrait, though the stylized figure does not particularly resemble that of the artist. Rather, it’s as if she sees herself reflected in her African heritage, or that heritage reflected in herself.

Wood, Quarles, and Wilson take three completely different, maybe even incompatible, approaches to figurative painting. If I try to imagine a three-person show combining their works, I just imagine a gallery exploding from all the conflicting energies. In fact, you might even say they explode the very idea of “figurative painting.” But they all seem to pose, with equal skepticism, the same question that Wood has framed: “What does ‘from life’ even mean in this day and age?” They may not be painting “from life” in the traditional sense, but they are painting feelings from life in all its difficulty. Wood’s vision is dark, Wilson’s more hopeful, while Quarles maintains more of an emotional neutrality. But one thing they have in common is a refusal to accept the human body—and therefore, implicitly, the human person—as an already known, settled thing. I don’t know if any or all of them would accept the label of post-humanist, but all of their work implies that old ideas of the human will no longer do.