There are no passageways or partitions on the fourth floor of Manhattan’s New Museum. The elevator opens onto an undivided room. The room is rectangular, and large enough that, from its threshold, you can’t tell what style of portraits are presently hung on its walls, though some are over five feet tall. The dim lighting makes it hard for a visitor to see.

Despite these viewing conditions, it’s best to stand still for a few moments. Observe how, even at this distance, even in this lighting, the paintings’ muted tones—smoky ochres, milky grays, velvety blues and pinks—envelop you in their melancholy mood. The mood grows more intense as you move toward the canvases. Soon, with a sense of revelation, you see that it’s shared by the figures on the wall. Although they appear to sit, stand, lounge, and even pose, the best part of them remains elsewhere. Each is lost in a daydream.

Each figure may even be a daydream. For the Ghanaian-British painter Lynette Yiadom-Boakye paints imagined portraits: characters who grow out of her imagination, out of memories, old photographs, or “any number of preoccupations,” as she titled a painting from 2010.

The conceit of fiction does away with positivism, allowing Yiadom-Boakye to blur character and style. What results is a portraiture that reconciles contradictory merits. On the one hand, her work is openly self-reflexive: Yiadom-Boakye paints with thick, naked brushstrokes, renders clothing as blocks of color, and often leaves her canvases unfinished. On the other hand, and more surprisingly, she conveys inwardness with haunting ease. “Subtleties of human personality it might take thousands of words to establish are here articulated by way of a few confident brushstrokes,” as Zadie Smith wrote recently in The New Yorker.

Born in 1977, Yiadom-Boakye grew up in London, where she received her MFA at the Royal Academy in 2003. As a young painter, she was interested in figuration, a genre that can be subtly political when handled well (think of William Kentridge or Marlene Dumas). Unhappily, Yiadom-Boakye, whose exhibition, “Under-Song for a Cipher,” is at the New Museum until September 3, tackled politics before developing the necessary technical skills. In fact, and by her own admission, her political engagement served as a substitute for technique. “It wasn’t painting as a practice,” she told the curator Naomi Beckwith in a 2013 interview. “It was more about telling a crazy story using paint as opposed to learning to work with oil or watercolor.”

First (2003) and Politics (2005) are representative of this early work. In First, a middle-aged woman, half-dressed in a striking red robe, smiles out of a crude, minstrelesque face. The younger celebrities in Politics are rendered with more delicacy, but here too the program is decidedly satirical.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Both works use the rhetoric of black grotesque. And that’s meant to convey… well, what exactly? We could speculate that these paintings express Yiadom-Boakye’s social unease, that they dramatize and critique the objectification of black women. But these are constructions artificially placed upon the paintings; no real anger or fury or sadness sensually emerges from them. If anything, it’s those incandescent clothes (the red robe in particular) and the weirdly menacing backgrounds that are the canvases’ stronger passages. By contrast, there’s something perfunctory about the twisted faces.

It’s a story familiar to young artists: You have something to say, you’re impatient to say it, and subject matter—here, identity—takes the place of form and technique. In her defense, Yiadom-Boakye quickly grew unsatisfied with painting political statements. “I hadn’t really defined a style yet,” she told Beckwith. “Because I hadn’t got to grips with painting yet.” Accordingly, she took a step back to explore “the actual power that painting could have.”

This required turning away from subject matter—not just politics and social issues, but also history and setting. The human figures remained, but they too underwent an ontological transformation. In Yiadom-Boakye’s early work, humans had an a priori existence; they stood for certain arguments, types, or themes. That approach was reversed sometime in the mid-2000s; now the figures emerge from the process of painting.

The shift can be observed as early as Casein (2007) and Chord (2007). These paintings are mood-pieces of ochre, brown, and black, with only the barest white dots that over time become eyes. Even once those are recognized, and the rest of the human face comes into focus, the figures maintain a tenuous, flickering existence. Their skin is only a few shades away from the background, and there’s little sense of physical presence. It’s as if they haunt a canvas that can’t quite pin them down.

For a portraitist, it’s a strange approach. But perhaps we aren’t dealing with portraiture. Abstract painting, as defined by Octavio Paz, “suggests contemplation to us—not of what it shows but of a presence which the colors and forms evoke without ever entirely revealing: a presence that is in fact invisible. [It] is a language which cannot say, except by omission and allusion: the picture presents us with the signs of absence.”

Yiadom-Boakye’s figures should be understood in this context. Like longed-for lovers, they are the goal of her work; she yearns for them through her paint, through contrast, color, and luster. Likewise, since their physical existence has been denied, she makes its fictiveness everywhere apparent. The sadness of this gesture is masked by bravura: Yiadom-Boakye flattens space, and paints humans and their surroundings with identically brisk brushstrokes.

She places her figures in dehistoricized settings (empty rooms, bare landscapes) or against monochrome backgrounds—a decision that certain critics read as a blistering critique of Western art. Though well-intentioned, this simply overstresses her commitment to realism. It’s better to imagine Yiadom-Boakye as filling up a helium balloon: too much abstraction, and the spirits fly away; not enough, and the painting won’t get off the ground.

That said, there is an art-critical point here, one that has little to do with race relations, at least in any obvious sense. Yiadom-Boakye takes figures out of history and locates them squarely in the world of painting. In doing so, as Hilton Als notes, she short-circuits “potentially Marxist or Barthesian reading of her ‘texts.’” What you’re left with is an individual style. These paintings are hermetic in the best way.

Over time, working at the astonishing rate of one canvas a day, Yiadom-Boakye has finessed her technique, adding a range of colors and a richness of figural detail. Combined, they feed the increasingly poignant illusion of human presence. For example, in a mature work, Citrine by the Ounce (2014), the lemon-yellow background has crept into the under-painting of an otherwise darker-brown complexion. The result is delightfully ambiguous: You don’t know who or what is moving you.

The 17 canvases on display in “Under-Song for a Cipher” were all made between 2016 and 2017. They show Yiadom-Boakye embracing and exploring the possibilities of fiction—in particular those of setting. In Medicine at Playtime (2017), for example, a dreamily handsome man sits in a room that is morphing into his dreamscape. The floor is a chessboard straight out of Alice in Wonderland; the smudged brown walls seem to be giving way to smoke. While all dreaming carries the trace of dysphoria, it’s important to note how essentially hospitable, how humane and un-ominous, the painting’s texture is. Physical reality is dissolving, but there are no histrionics or sense of loss.

Canvases like Light of the Lit Wick (2017) and Brothers to a Garden (2017) go a step further to collapse setting and character in a formal pact. In Light, a dancer elegantly stretches her hands upward against an olive backdrop patterned by two large circles, the glow of a candle and its shadow. The titular metaphor has been neatly realized—perhaps too neatly. Brothers to a Garden, by contrast, achieves an almost transcendent counterpoint by playing the lush navy-blue jacket against a dry sandy-brown wall. Yiadom-Boakye has here rendered her character’s fingers with unusual delicacy, a tenderness that radiates out to the flower pattern that surrounds them.

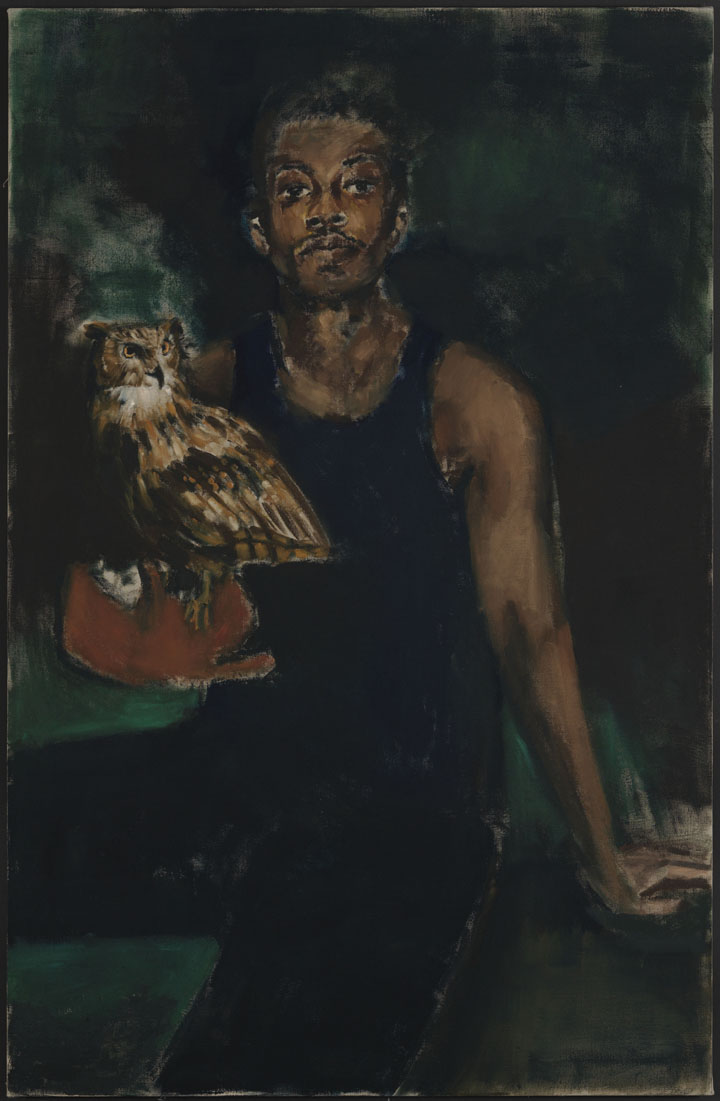

A more playful work, The Matters (2016), nicely captures Yiadom-Boakye’s use and inversion of realism. As in many of her paintings, it shows a man with a bird; in this case, an owl perches on his hand. He sits—floats, really—against a smoky black atmosphere shot through with green. He is beautiful, lithe, and Yiadom-Boakye has taken great pleasure in presenting his skin’s gradations. In fact, she’s indulged herself: Few faces have so many shades of brown; few arms are tanned that way—at the shoulders and wrists, but not the biceps. But these are a make-up artist’s complaints. Like the dancer in Light, the man is meant to glow with confidence. And in that regard, he’s a total success. In fact, you’re so taken that you almost forget the owl resting on his falconer’s glove—which, when you focus on it, is just a giant orange splotch.

Vigil for a Horseman (2017) is the most ambitious work on display. A large triptych that occupies most of the gallery’s right wall, it’s composed of three portraits—two over six feet wide—of muscular men lying on a red-and-white-striped divan. Like many of Yiadom-Boakye’s recurrent figures, the men look very similar, but they aren’t quite the same, and the triptych is best understood as a set of variations.

In any case, it’s Yiadom-Boakye’s color palette that makes the paintings. She has used the candy-cane pattern before, in 11 pm Thursday (2009) and Six am Wednesday (2009). And there, as here, the warm red is set against the cool skin tones of the human figures. It’s the sort of striking contrast often deployed for cheap eroticism (red is amatory), but Yiadom-Boakye’s intentions are more subtle.

There’s no sense of invitation, let alone sexual approach, in this triptych. In fact, we are painfully aware of our distance from the half-dressed men in repose. This is partly because of how self-involved they seem (two look past us, and the third is almost weary). But there is also a formal effect at work: Yiadom-Boakye renders her walls in a flesh hue that absorbs and diffuses the red’s eroticism. The triptych’s sexual drama is thus transferred to, or perhaps originates from, a disembodied, contemplative, and finally abstract plane.

Yet it’s no less erotic for that. Moreover, its eroticism is emancipatory: Arousal here is a response to color, not the identity, race, or gender of the figures. The painting, as Paz would put it, does not “weave a presence, it is presence.”