When the Bellamy Creek correctional facility’s longtime kitchen officer decided to leave in 2014, David Angel requested the position. Angel, who was nearing retirement, had worked at prisons all over Michigan, including stints at three maximum-security facilities. “I wanted a permanent position for my last few years in the department. I had a lot of respect among the prisoner and officer staff, and I thought I could do the job and keep people safe,” he said. “Um… I was wrong.”

The Bellamy Creek kitchen is typical for a Michigan prison. Sixty incarcerated men staff it, doing everything from slicing potatoes with tethered knives to working the dish tank. Angel’s job was to provide security while six or seven outside employees oversaw the operations. The employees were new hires by Aramark, a food-service company recently contracted by the state to run its prison kitchens.

“It was a constant daily struggle,” Angel recalled. At first, it was the little things: Food was spilled but never cleaned up. Meals were served late, or the kitchen would run out of food and the staff would have to swap ingredients. “I saw peanut butter substituted for a hamburger patty more times than I care to count.”

Then came the day that he noticed spoiled bananas being unloaded from the supplier’s truck. He told the driver to take the bananas back but was refused. That day, he decided to wheel the bananas over to a dumpster. But trucks kept arriving with more bad food: “I threw out 700 pounds of rotten potatoes once.” Nevertheless, the spoiled food made its way into the kitchen, or fresh food would become spoiled because of Aramark’s poor storage practices, Angel said. He grew concerned about the safety of the food. “That’s when I saw maggots under the big commercial mixer.” He alerted his supervisor.

Angel laid the blame squarely on Aramark, and he wasn’t alone. Michigan’s switch to a privatized prison-food system was supposed to save the state money—$16 million, or more than 20 percent of what Michigan had been paying to feed the 44,000 people held in its prisons. But in order to make the numbers work, Aramark’s three-year, $145 million contract required the company to slash costs to an average of $1.29 per meal. One of the ways large companies like Aramark can do this is by taking advantage of economies of scale to get better prices on ingredients; they can also reduce quantities and serve lower-quality, less nutritious food. Probably the most effective way is to slash the payroll. In Michigan, unionized corrections workers earned $15 to $25 an hour, but the Aramark employees who replaced them were paid as little as $11 an hour.

As the months passed, stories like Angel’s began cropping up at prisons around the state. At the G. Robert Cotton facility, a prisoner spotted maggots on a vegetable slicer. At a neighboring facility, 30 people fell ill with foodborne illness after fly larvae were found crawling around the food-service line. At a prison farther north, an Aramark employee was caught serving meatballs fished out of a trash can. The state fined Aramark $200,000 for unsanitary food preparation, substituting nutritionally inferior ingredients, and routinely shorting prisoners on calories. In 2014, protests erupted throughout the state.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

In 2015, Michigan and Aramark terminated their contract, over a year early. But prisoners and guards had little reason to celebrate, because the state quietly replaced Aramark with another prison-food giant, Trinity Services Group. The problems continued under Trinity, and by 2016, a second round of protests had erupted. Most of these were peaceful, but one, in the Upper Peninsula facility of Kinross, led to what the state Department of Corrections acknowledged internally was Michigan’s first prison riot since 1981, though some officials deny this publicly. No one was seriously hurt, but it cost the state nearly $1 million in damage. “It was a powder keg,” Angel said. (Neither Trinity nor Aramark responded to requests for comment.)

“This [situation] has created an environment of theft, extortion, and robbery—all in the name of survival,” said Ramone Wilson, who is imprisoned at the Cotton facility. “If you’re on an empty stomach, then you’re desperate.”

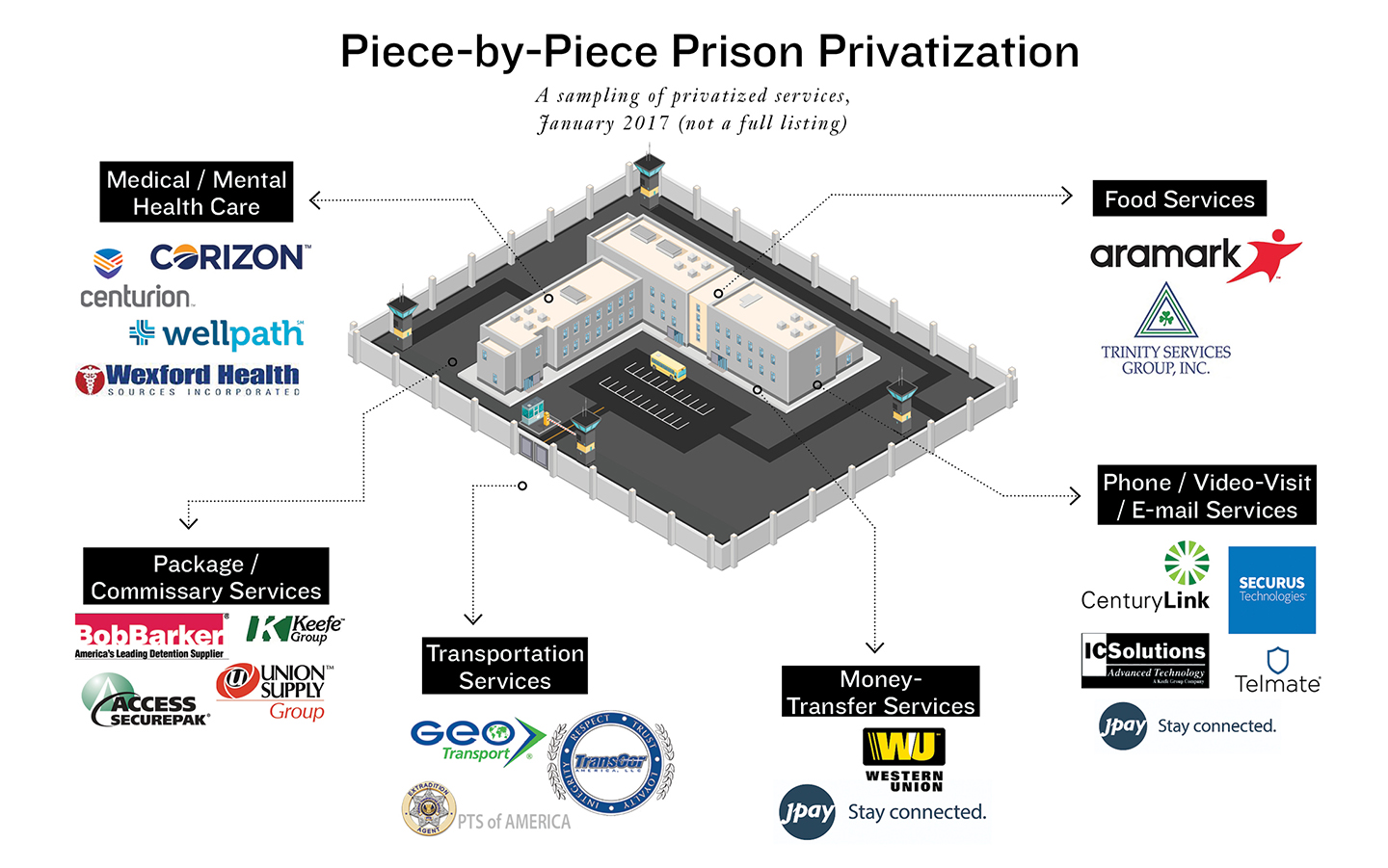

These days, Michigan’s for-profit prison-food experiment has few cheerleaders. But it’s hardly an aberration; rather, it is just one of the most flagrant examples of private companies taking over core services in the United States’ publicly operated jails and prisons. Hadar Aviram, a legal scholar, calls this phenomenon “piecemeal privatization.” She warns that, while the problems with privately operated prisons have been well documented, “focusing on private-prison companies misses the fact that public correctional institutions are also, essentially, privatized.” Fully private prisons hold less than a tenth of the nearly 2.2 million people incarcerated in America. Privatized services, by contrast, affect nearly everyone in the system.

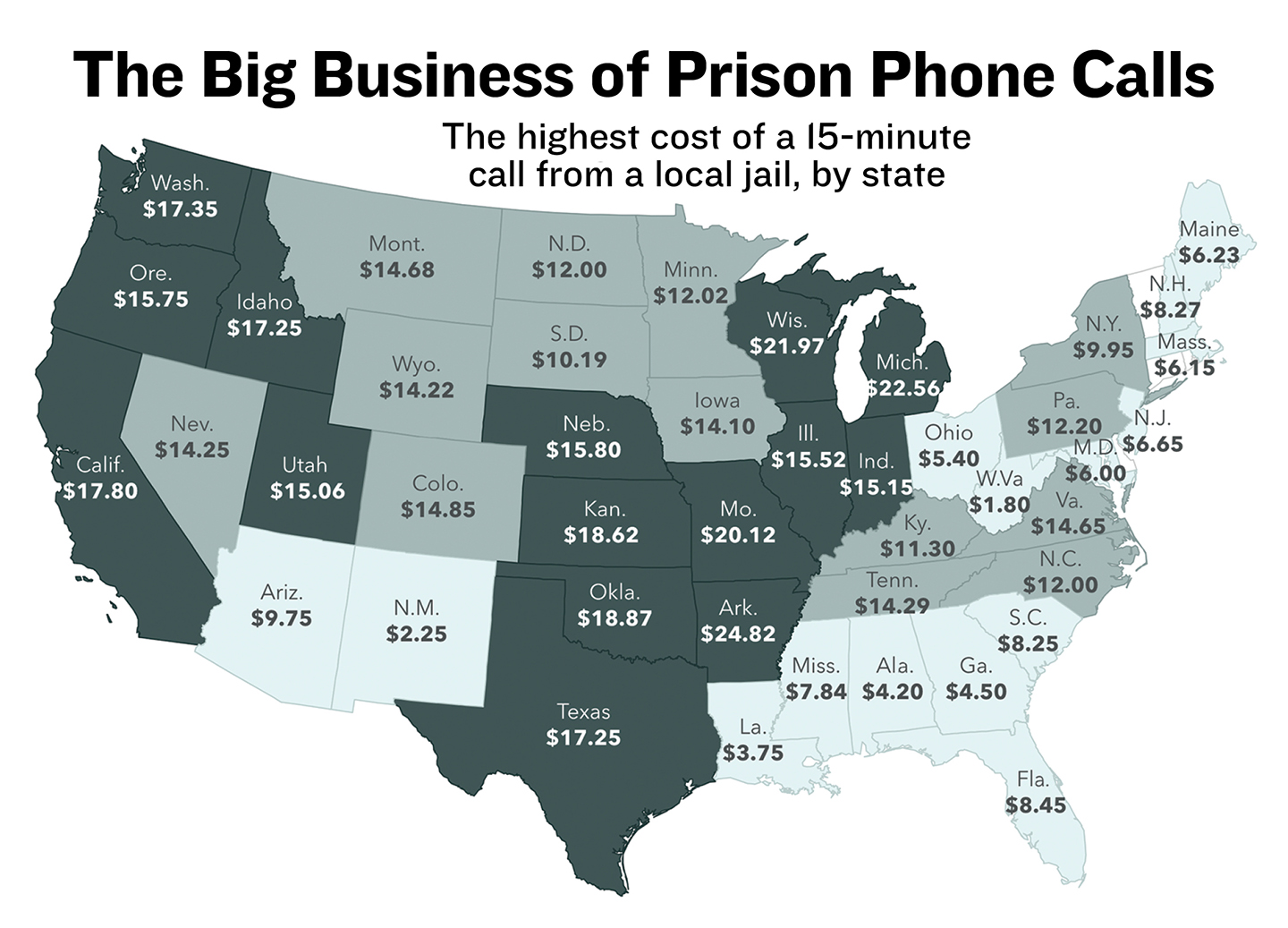

Because of this reach, the market for privatized services dwarfs that of privatized facilities. The private-prison industry’s annual revenues total $4 billion. By comparison, the correctional food-service industry alone provides the equivalent of $4 billion worth of food each year, according to Technomic, a food industry research and consulting firm. Corrections departments spend at least $12.3 billion on health care, about half of which is provided by private companies. Telephone companies, which can charge up to $25 for a 15-minute call, rake in $1.3 billion annually. The range of for-profit services is extensive, from transport vans to halfway houses, from video visitations to e-mail, from ankle monitors to care packages. To many companies, the roughly $80 billion that the United States spends on corrections each year is not a national embarrassment but a gold mine.

Today, a handful of privately held companies dominate the correctional-services market, many with troubling records of price gouging some of the poorest families and violating the human rights of prisoners. But the problem doesn’t end there. These companies are often controlled by private-equity firms, which through financial alchemy transform the prison-industrial complex into lavish returns for pensions, endowments, and charitable foundations. And, as successive administrations have ramped up immigration enforcement, they’ve also squeezed money out of immigrant detention.

Bianca Tylek, the founder of Worth Rises, an advocacy group that tracks commercial interests in corrections, has catalogued 3,100 companies with a financial stake in mass incarceration. Her findings were released last April in a Corrections Accountability Project report and include not only the well-known, publicly traded private-prison contractors but also divisions within companies with household names like Amazon, General Electric, and Stanley Black & Decker. In addition, dozens of boutique firms are dipping deep into the corrections-industry well, from Wall Street Prison Consultants, which provides advice to white-collar offenders, to a lawn-mower service that sells only to prisons. “We’ve underestimated the size of the prison-industrial complex,” Tylek said. “Every estimate you’ve seen until now is a conservative one.”

Or as Alex Friedmann, associate director of the Human Rights Defense Center and managing editor at Prison Legal News, put it, “Pretty much every conceivable service in the public prison system has been privatized in one form or another, with the exception of putting people to death.”

Friedmann has good reason to know. He spent 10 years in Tennessee’s prisons and jails, and in 1990, when his sentence began, most services were still run in-house. But privatization was on the horizon. At the time, he was optimistic about company-run services; the state-run prison system didn’t exactly have a stellar reputation. “I was in favor of privatization,” he said. “The big draw was rumors of free cold soft drinks in the chow hall. If you’re locked up, the amenities of life are pretty few, so that’s remarkable.” Two years later, he was sent to Tennessee’s South Central Correctional Facility, run by the corporation CCA (now CoreCivic). Once he arrived, he said, “I figured it out. Soft drinks are just sugar syrup and water, and thus cheap,” allowing private companies, he speculated, to meet state caloric requirements at little cost. Over his six years at South Central, he realized the for-profit companies had somehow made prison life worse.

Friedmann, then 23 years old, intuited a wave of privatization on the horizon, so he reached out to Prison Legal News and asked if he could write about it. One of his first articles, published in 1997, tells the story of six incarcerated men “roasted alive” in a privately operated prison transport van in Florida. “Ironically,” he wrote, “there are more regulatory guidelines for shipping cattle or other commodities across state lines than for extraditing prisoners.”

The next year, he started his own newsletter, Private Corrections Industry News Bulletin, to keep track of privatization trends across the country. His neatly typeset bulletin was prescient. In 1990, Tennessee was just flirting with privatization. By 2018, over a third of the state’s 22,000 prisoners were housed in private prisons. All health care at public facilities is contracted out, at a cost of $95 million per year. Phone services, e-mails, and money transfers are all private. Food service is private. Even the transport vans are private. For misdemeanors, probation supervision is privatized, with the company’s fees paid by offenders.

Today, Friedmann is a leading advocate against privatized prisons and prison services. He has a salt-and-pepper beard and wire-rimmed glasses and speaks with the practiced precision of a high-school history teacher who has given the same lecture for two dozen years—which, in a sense, he has.

“Most people have no idea what prison’s like except from TV. It’s out of sight, out of mind.” That’s by design, Friedmann says. “Prison walls don’t just keep prisoners in, they keep the public out.” He said the privatization of services has benefited from the citadel secrecy of correctional facilities. “Privatization of services in jails and prisons just doesn’t rise to the level of headlines.”

Consider prison transport. He first investigated the subject in 1997 and followed up with a comprehensive 11,000-word cover story in 2006, but private prisoner transport became mainstream news only in 2016, when the Marshall Project and The New York Times published an exposé on the subject. Their reporting showed that companies forced drivers to pay out of pocket for hotels; as a result, they often chose to drive nonstop, and prisoners said they were forced to urinate or defecate on themselves. While transferring a prisoner from Kentucky to Mississippi, a guard from the company Prisoner Transportation Services of America dismissed the man’s complaints of stomach pains and refused to stop. Soon after, the man died of a highly treatable ulcer. At least 56 prisoners have escaped from for-profit transportation companies since 2000, with at least 16 committing crimes while fleeing. By comparison, California, Texas, and Florida, whose state-run transport systems shuttle some 800,000 people every year, reported a single escapee over the same period.

Prison Legal News published its first major story on privatized prison health care in 2000, and abuses by that industry have been confirmed by subsequent media reports and lawsuits. Among the most explosive was a 2014 report by the Southern Poverty Law Center and the Alabama Disabilities Advocacy Program on the company Corizon. Beginning in 2012, Corizon was awarded what would ultimately amount to a $405 million contract to provide health care to Alabama’s 25,000 prisoners. As is typical for private companies, Corizon understaffed facilities to save money. Only 15 physicians served the entire state—which meant a caseload of more than 1,600 patients per doctor. Some facilities had no full-time doctors, with dire consequences. A prisoner at the Kilby Correctional Facility had a stroke, but the underqualified medical staff waited to decide what to do until the doctor arrived the next morning, at which point the damage had been done; that man must now use a wheelchair. A prisoner in dialysis went into cardiac arrest, but because the medical staff on duty didn’t know how to use the emergency equipment, he died.

Nor are these problems limited to Alabama; Corizon recently lost contracts in Georgia, New Mexico, and Arizona and at the Rikers Island jail complex in New York City. The company has been embroiled in over 1,000 lawsuits.

Despite such troubling records, correctional agencies continue to hire these companies on the grounds they will save taxpayer dollars. “The big draw is the economic pitch that the companies can save them money, and they don’t have to deal with medical care or food,” Friedmann said.

The evidence that these companies actually save money is, at best, mixed. But the companies can sweeten the deal with commissions paid to the states. “‘Commission’ is a euphemism for ‘kickback,’” Friedmann said. “It really started with the prison phone companies,” which compete for monopoly contracts with prisons and jails, promising to share a percentage of the fees that the incarcerated are charged. These kickbacks can return up to 94 percent of a company’s sales revenue to the state. To make a profit, the company has to charge the incarcerated and their families high rates. Some cash-strapped jurisdictions now depend on these kickbacks to fund facility operations and law-enforcement activities, and correctional agencies are clearly hooked on the extra hits of cash. When the FCC considered restricting these commissions in 2013, the National Sheriffs’ Association threatened that the jails would be forced to end phone calls altogether.

These backward incentives can result in crushing costs, particularly in jails. According to the Prison Policy Initiative, a 15-minute in-state call from jail costs $5.74, on average. In one Arkansas jail, that call costs $24.82. Correctional telecom companies like Global Tel*Link and Securus, the two industry titans, are also expanding into video visitation. At first, Securus’s contracts sometimes mandated that video visitation—with typical rates around $1 per minute—replace previously free in-person visitation, but after outcries, Securus removed these provisions. However, because of the kickbacks and the reduced security costs associated with video visitation, many jails have gone ahead and implemented the policy anyway. A 2015 study by the Prison Policy Initiative found that 74 percent of jails that adopt video visitation end up reducing or eliminating in-person visits. In a scene worthy of dystopian fiction, visitors may sit in a room next to their loved ones but must pay to use a grainy video-visitation kiosk to see them.

In 1833, two years before Alexis de Tocqueville published Democracy in America, he helped write a lesser-known study, On the Penitentiary System in the United States and Its Application in France. The report was generally damning (“the prisons…offer the spectacle of the most complete despotism”), and Tocqueville noted America’s penchant for inviting private profit-making into public prisons. Contractors who exploited the prisoners for labor also profited from selling them essential items:

The contractor is the most important person attached to the prison. The overseers of the workshops, the contre-maîtres, cooks, bakers, victual sellers, laundresses, apothecaries, attendants of the sick, servants, hommes de peine, and all others, whose functions are subject to no surveillance whatever, are chosen by the contractor…. It is clear that he does not accept the contract except with almost certain chances of great profit.

In 1887, Congress passed a law eliminating contract labor in the federal system, and the states soon followed. The market described by Tocqueville collapsed, and for the first half of the 20th century, public correctional agencies assumed nearly all aspects of management for adult prisons, from food and clothing to the commissary and health care.

But then a series of disastrous policies in the 1960s and ’70s—beginning with President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Crime—led to an explosion in the prison population. From 1972 to 1985, the number of people in America’s prisons more than doubled. Prison conditions began to deteriorate, and in 1974, a Texas prisoner named J.W. Gamble filed a lawsuit complaining that the state denied him proper medical treatment after a 600-pound bale of cotton fell on him during a work assignment. The case, Estelle v. Gamble, made it to the Supreme Court, where Justice Thurgood Marshall wrote for the majority that “deliberate indifference to serious medical needs of prisoners” was a violation of the Eighth Amendment’s protection against cruel and unusual punishment. By 1985, prisons in 34 states were under court supervision for violating the constitutional rights of prisoners. States, hobbled by budget shortfalls, struggled to comply with court orders. At the same time, the prison population continued to swell. President Ronald Reagan’s War on Drugs had begun, and its harsh sentencing laws guaranteed a steady influx of newly incarcerated Americans.

At this point, policy-makers could have reckoned with the wisdom of incarcerating half a million people. Many suggested diverting money from law enforcement and incarceration and into social programs to address issues such as joblessness that contributed to crime. But the Reagan administration had something else in mind. The president assembled an advisory body of executives from the country’s largest banks and corporations and tasked them to “work like tireless bloodhounds” to cut costs and ferret out inefficiency in the federal government. The advisory body laid the groundwork for a 1988 report that recommended opening up functions like the postal service and air-traffic control to private enterprise. When it came to criminal justice, the administration, citing the notoriously inhumane conditions of America’s public prisons, recommended that the Department of Justice “give high priority to research on private sector involvement in corrections.”

A cynical way to look at correctional privatization is just business smelling blood and going in for the kill; the generous interpretation is that companies swooped in to save a failing government model. Regardless, the administration used the dismal state of affairs in government-run jails and prisons as a pretext to promote the privatization of every conceivable aspect of the correctional system.

On a rainy Friday night in March, I drove to the Hope Community Church on Detroit’s east side to visit a support group for families of the incarcerated. I was there to better understand the financial toll of having a loved one in a Michigan prison. The group meets every other Friday evening in an alcove to the right of the church’s nave. There I met a woman named Eunice, whose 45-year-old son, James, has been in and out of Michigan’s prisons for the past eight years. She spoke in measured tones, thumbing a knitted scarf while she recounted the financial burden of her son’s imprisonment.

“You can’t lift a finger without somebody profiting off of it,” she said. To keep costs low, she limited phone calls to her son to every Saturday morning, for which Global Tel*Link charged her $3.00 for 15 minutes, plus a $3.95 fee simply for putting money into the account. “You put $15 on there, but you only get $10 worth of phone calls,” she said. (The state has since capped prison phone calls at 16¢ per minute, but the same call from jail can run as high as $22.56.) If Eunice wanted to send an e-mail, JPay, a privately owned company that has been dubbed the Apple of the prison system, charged her a starting rate of 25 cents per message.

Every few months, she would order a SecurePak care package from the Keefe Group, for up to $85 plus a $2 handling fee. In between care packages, she’d deposit $100 into her son’s Keefe commissary account, plus a fee of $2.95, so he could buy the necessities like toothpaste ($3.82) and deodorant ($3.49) that many Michigan families say aren’t provided in sufficient quantities by the prison. Her son, who is diabetic, would also have to use that money to pay Corizon’s $5 co-pays if he wanted to see a doctor.

Some argue that the Michigan Department of Corrections has an incentive to permit all these charges. As with the phone companies, the various contracts are structured to kick back a cut of the fees to the state. The department receives 5 cents for every e-mail sent, $10 for every tablet computer sold, and 50 percent of printing fees if prisoners choose to save e-mails on paper. For each $100 care package, the department receives $19. If someone purchases $100 worth of commissary goods, that’s another $19.

Chris Gautz, a spokesman for the department, said that all commissions are deposited into its Prisoner Benefit Fund, which may be used to pay only for items that serve prisoners, like cable TV and exercise equipment. “Michigan has never looked at [commissions] as a revenue generator,” he said. But prisoner benefit funds have little oversight, and while there’s no evidence that Michigan has ever diverted the money, several other jurisdictions have. In Los Angeles, 49 percent of funds dedicated to inmate welfare went to routine jail maintenance, according to a 2010 report from the Sheriff’s Department. A 2011 budget report from Jefferson County, Colorado, revealed that 89 percent of phone and commissary commissions were used to pay staff salaries. An Orange County 2011 Internal Auditor’s report found that less than 4 percent of its “Inmate Welfare Fund” fund went to programs benefiting prisoners.

Eunice estimated that she has spent $75 to $100 a month, on average, during her son’s years of incarceration—a sum that likely approaches $5,000. “It put a dent in my pocket,” said Eunice, who recently retired, but “I was able to [afford it].” Many others aren’t as fortunate, though. According to a recent study exploring the hidden community costs of incarceration, 82 percent of families are responsible for phone and visitation costs—and of these, one in three families go into debt to pay for them. Of the family members responsible for these costs, 87 percent are women, and because of the racial bias in American criminal justice, the majority of those women are likely from communities of color.

A few days after I met Eunice, I caught up with June Walker, who founded the support group Eunice attends. We ate lunch at a diner a few blocks away from the church. Walker said many people might think, “What’s the big deal about a $3.95 fee?” But it’s not just one fee; it’s a constant trickle. “It’s death by a thousand pennies.”

Walker gestured out the window at a neighborhood still scarred by the 2008 recession. Census tract 5129, across from Hope Community Church, has a median annual income of $16,992. “Most people around here just don’t have a lot of pennies to spare.”

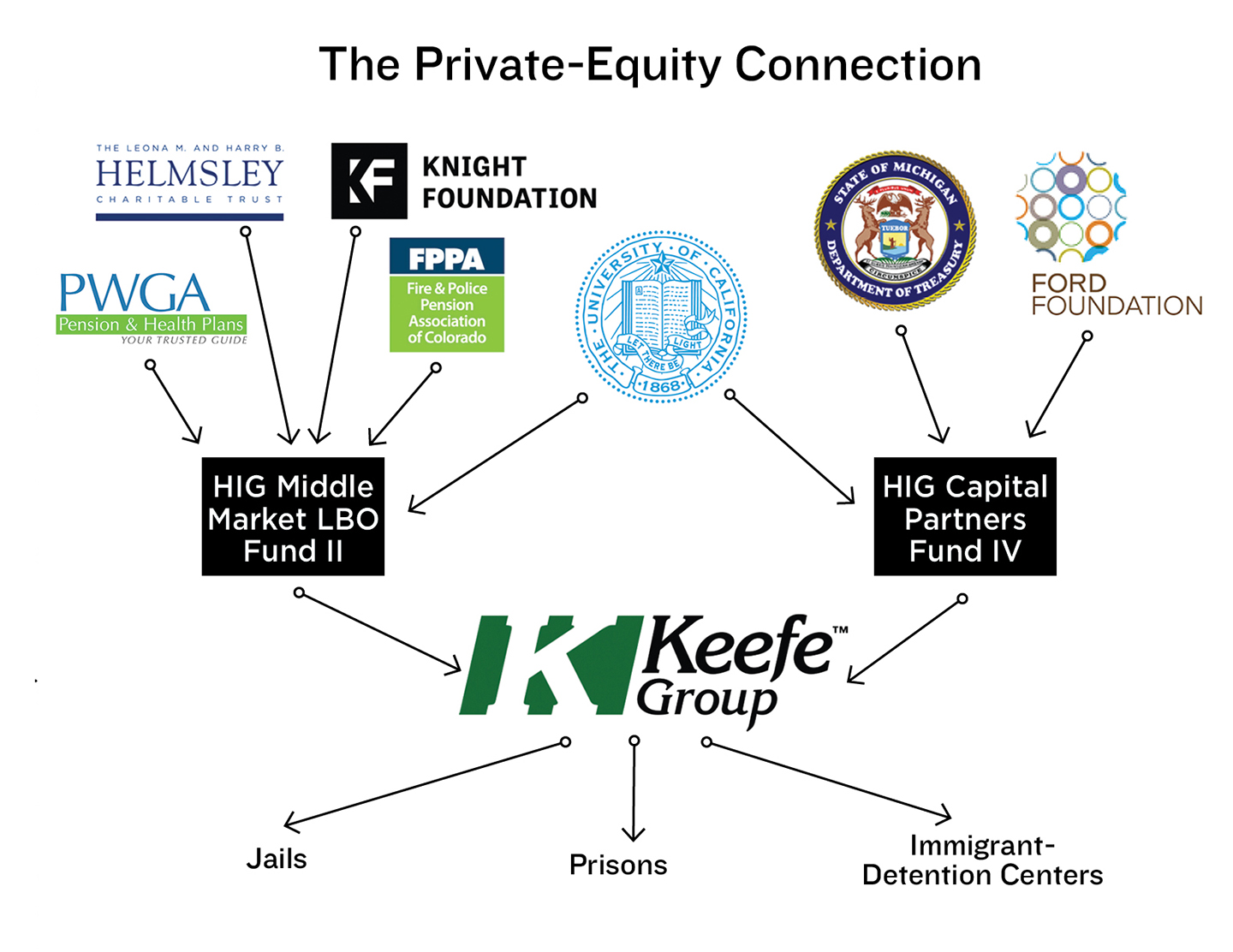

Some 1,400 miles away, just across from the Four Seasons Hotel in downtown Miami, a 35-story office building angles skyward, covered in missile-resistant glass the color of the Bay of Biscayne. The building is home to a number of financial companies, including a private-equity firm called HIG Capital, which manages more than $30 billion in assets. HIG has one of the more unusual side hustles of any private-equity firm: Over the past decade, it has quietly helped consolidate correctional phone, food, commissary, and health-care companies into behemoths that dominate their markets and, according to critics, drive prices up for families while lowering quality.

A closer look at HIG reveals some surprising truths about the relationship between high finance and incarceration in America. HIG entered the correctional industry in 2004, when it merged T-Netix and Evercom, then two of the leaders in the correctional calling market, to form what is now Securus. After the 2008 financial crisis, profits at Securus accelerated just as economies in cities like Detroit crashed. HIG sold the company in 2011, but its growth trajectory had been set. In a 2015 company presentation obtained by The Huffington Post, the company boasted that the tens of billions of dollars the government spends on corrections each year offers “a large, recession-resistant and stable market” and that Securus was “well-positioned for organic growth.” Today, Securus provides phone services to 1.2 million men and women incarcerated at approximately 3,400 facilities, with likely annual revenues of over $500 million.

HIG then used a similar playbook to consolidate the correctional food and health-care industries. First, in 2012, HIG acquired Trinity Services Group, the food and commissary company that was partly responsible for Michigan’s debacle. Two years later, HIG acquired Swanson Services Corporation, a leading provider of commissary goods operating in 41 states, which was integrated into Trinity. Two years after that, HIG merged Trinity with commissary giant Keefe Group. Today, prisoners nationwide spend an estimated $1.6 billion each year on commissary goods such as food, clothing, and hygiene items like toothpaste. Some commissaries are state run, but estimated revenues suggest that HIG’s correctional food company likely profits off of more than half of all prisoner spending nationwide; it is clearly the largest commissary company that has ever existed.

During that time, HIG also moved into prisoner health care, investing in California Forensic Medical Group, which serves 90 percent of outsourced county jails in California, and merged it with industry heavyweight Correct Care Solutions. HIG’s health-care company, Wellpath, formed last October, is now on track to become one of the largest companies in the correctional health-care industry, with $1.6 billion in revenue.

Given these numbers, it’s fair to say that HIG has played a significant role in creating some of the largest correctional services companies in history. Yet HIG has a different interpretation of its role in the privatized prison-services industry. In a comment to The Nation, Jeff Zanarini, a managing director at HIG, rejected the claim that the company’s consolidation strategy has radically reshaped the prison landscape. He noted that HIG has invested in hundreds of companies, only a small fraction of which have ever provided correctional services. “In fact,” he wrote in an e-mail, “given the size and scope of the two companies referenced above [Keefe’s parent company, TKC Holdings, and Wellpath] that we currently own, it is accurate to say that H.I.G. plays ‘no role whatsoever in shaping the nation’s jails and prisons.’”

Zanarini further suggested that, to the extent HIG does play a role, it is a positive one. “The two companies we do own are focused on improving the health and well-being of prison populations, while providing services that are far superior to the available alternatives (i.e., the provision of such services by state and local governments),” he wrote. “So, again, contrary to your thesis, our portfolio companies aim to provide higher quality services to inmates and their families at more affordable prices.” As one example, he cited Wellpath’s predecessor, Correct Care Solutions, whose behavioral health division was widely praised for its dramatic improvement of appalling conditions at Bridgewater State Hospital, a Massachusetts medium-security mental health facility. After only five months of new management, The Boston Globe described Correct Care’s transformation as “remarkable, beyond the imagining of mental health advocates.”

And yet, as the failings of Michigan’s food service under Trinity shows, companies owned by HIG can also make things dramatically worse. Moreover, while these companies may indeed be small relative to the size of HIG’s portfolio, as Zanarini suggests, they loom large in the landscape of America’s jails and prisons, dominating entire sectors of the for-profit correctional services industry. Take Keefe Commissary Group. In a 2012 bid submitted to the Wisconsin Department of Corrections, Keefe proudly claimed that it was five times the size of its nearest competitor. In states with fully outsourced commissary services, the bid noted, Keefe controlled 98.4 percent of the market by prisoner population. The only exception was South Dakota, which was serviced by a competitor, a company called CBM. Keefe was quick to point out in the bid, however, that Keefe Group was CBM’s main supplier.

While HIG has spent the past decade carving out a niche in the prison commissary and health-care sectors, it’s far from the only private equity firm with stakes in the corrections business. Indeed, when Bianca Tylek was sifting through the 3,100 companies in her Corrections Accountability Project report, she noticed a peculiar trend: “On a systemic level, the thing that really emerged is how active private equity has been in shaping the prison-industrial complex and how many of the biggest actors in the field are owned by private-equity companies.” She paused. “In fact, almost all of them are.”

Tylek said private-equity-brokered roll-ups—deals like HIG’s that bundle fragmented regional players into national conglomerates—have profoundly reshaped the correctional-services industry; “without PE shops, these companies could not have become as big and as exploitative as they are today.”

It took me only a few Google searches to grasp how difficult it would be to prove Tylek’s intuition about private equity’s negative effects on the correctional system. Anyone looking for insight faces three layers of opacity: Most correctional-services companies are privately held, meaning financial information is hard to come by; private-equity firms are lightly regulated, with few public-reporting requirements; and the correctional system is notoriously hostile to outside scrutiny.

At a loss, I called a friend who has worked in private equity, who said corrections is a niche industry that cuts across business sectors, so there are no analysts who look at it as a whole. He suggested calling Wall Street analysts who cover publicly traded private-prison companies, whose dealings are less hidden from view; none could offer any insight. I looked to academia, but several economists said no one studies the role of private equity in corrections.

I finally found Sabrina Howell, an assistant professor of finance at NYU’s Stern School of Business. She doesn’t study private equity in corrections, but she just published a study on the disastrous role of private equity in for-profit education. She and her co-authors obtained data on nearly 1,000 schools owned by private-equity firms. After controlling for confounding variables, they discovered that private-equity-owned schools have higher profits—but also higher tuition, sharp declines in graduation rates, more student borrowing, lower repayment rates, and dramatic increases in illegal activities such as recruiting quotas and misrepresentation of loan terms. Despite worse outcomes, private-equity-owned schools were better at capturing federal aid. “This is a purely rent-seeking phenomenon and is unambiguously not in students’ or taxpayers’ interests,” her study concluded.

After seeing my research, Howell said, “There are definitely parallels here.” In both cases, she pointed out, the government serves as middleman between company and consumer—via federal loans in education and via state contracts in prisons. Under this arrangement, what’s good for the company and the government might not be good for consumers. These misaligned incentives played a role in distorting the for-profit education market. “If anything,” she said, “in prisons the potential for misaligned incentives is much more extreme.”

The profound level of consolidation stuck out to her. “In principle,” she continued, “private-equity firms could combine companies to achieve economies of scale and drive prices down without a loss of quality.” But in practice, only a few companies dominate a given sector, enjoying monopoly-like conditions. Without hard evidence, Howell couldn’t speculate about the effects that extreme consolidation might have on this industry. But generally, she said, “it’s well established that having just one or two companies serving a market can yield monopoly pricing and collusive outcomes.”

Tylek was less guarded in her assessment: “These roll-ups and buyouts and sales aren’t just some esoteric financial deals. They exploit real people, particularly those from low-income, minority, and—increasingly—immigrant communities.”

In February 2018, Michigan’s then-governor, Rick Snyder, appeared in the Capitol rotunda to present his $56.8 billion annual budget to the state legislature’s appropriations committees. The otherwise soporific event was interrupted by chants of “Tricky Ricky” from protesters demanding that Snyder return correctional food services to state workers. The protesters weren’t particularly optimistic, but then Snyder dropped a bombshell. “We’ve worked with a couple of different private vendors,” he said. “The benefits of continuing on that path don’t outweigh the costs, and we should transition back to doing it in-house.” Nick Ciaramitaro, legislative director for the public sector union AFSCME Council 25, told the Detroit Free Press, “I give him credit. It’s one thing to try something—it’s another to admit that it didn’t work.”

Six months later, the food-privatization experiment in Michigan ended, and now, for the first time in decades, nationwide mass incarceration is showing signs of slowing. The companies providing correctional services see the writing on the wall. To insulate themselves, they continue to consolidate and diversify, with the same company that runs the phones also running, say, the prison store and selling software to help corrections officials surveil prisoners. Or the companies push deeper into the one market that shows no signs of flagging: Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention facilities.

Unlike in corrections, the majority of immigrant-detention facilities (an estimated 73 percent) are fully private—a well-publicized fact. Less widely known is that the same food, health-care, commissary, and financial-services companies that dominate America’s jails and prisons also profit off subcontracts with ICE detention centers, such as the notorious processing facility in Adelanto, California. Wellpath (owned by HIG) runs health care, and Keefe Group (also owned by HIG) runs the commissaries. Now, thanks in part to the center’s history of violations, the city of Adelanto has decided to end its contract with ICE and the private-prison operator Geo Group and will no longer host the facility.

The profits that companies like Keefe and Wellpath extract from immigration detention centers are admittedly small, a point pressed by Zanarini, who described detention centers as “an immaterial portion” of the companies’ business. Yet even if revenues are “immaterial,” they are still, based on information provided by HIG, likely to be millions of dollars—a fact that at least some of the funds’ investors might not like to be made public.

Private-equity firms don’t typically reveal their investors to the public. But by examining tax documents, government filings, and investment reports, I was able to make a partial list of HIG fund investors that benefit from mass incarceration and, to a lesser degree, immigration detention policies. The results were surprising.

A number of public pensions have invested in the HIG fund that controls Wellpath, including ones from Tennessee and Orange County, California, as well as the Ohio Highway Patrol’s. A wide range of organizations have invested in the HIG funds controlling the Keefe Group, including the Knight Foundation, the Sherman Fairchild Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the Police & Fire Pension Association of Colorado, and the Producer-Writers Guild of America Pension Plan.

In an unexpected twist, the State of Michigan Retirement Systems, which pays out correctional officers’ pensions, has $25 million in one of the funds that control Keefe and Trinity Services Group, according to a 2015 quarterly investment review and confirmed by Ron Leix Jr., the deputy public information officer at the Michigan Department of Treasury. Leix played down the multimillion-dollar investment, calling it “tiny.” Nonetheless, because the Michigan Department of Corrections contracts its commissaries and care-package service to Keefe, and previously contracted its food to Trinity, the department’s staffers, however indirectly, have benefited from the fees that Keefe charges prisoners and their families, and from the profits Trinity made from running the prison kitchens.

I called up David Angel, the retired Michigan kitchen officer, to ask him how he felt about having his pension paid out in small part from companies that also profit off of prisoners. “I don’t like it all,” he said. “You have them investing in something that could potentially be a conflict of interest.” He added that, if officers had known their pensions would be partly paid with profits from Trinity, the company that ran their kitchens into the ground, “we’d have maybe put pressure on the pension system to pull their pin on that.”

I also found that the University of California, which in 2015 announced to great fanfare its divestment of $30 million in private-prison stock, had $29.5 million committed to funds that control Keefe, according to a 2017 report detailing the university’s private equity holdings.”

Still, as uncomfortable as these investments make endowments and universities with lofty missions, few of us are spared. In a complex economy, it’s nearly impossible to avoid the tentacles of the prison-industrial complex. I’m no exception: The reporting for this article was supported by a grant administered through the University of California.

In 1998, Angela Davis popularized the term “prison-industrial complex” to describe the sprawling web of commercial and governmental interests in corrections, which seeks to sustain itself regardless of actual need. The term is as boring as it is foreboding, the phenomenon as predictable as it is intractable. The stark reality is that punishment in America has always had an appalling financial dimension. As Tocqueville observed in the 1830s:

The contractor, who sees nothing but a money affair in such a bargain, speculates upon the victuals as he does on the labor; if he loses upon the clothing, he indemnifies himself upon the food; and if the labor is less productive than he calculated upon, he tries to balance his loss by spending less for the support of the convicts.

In just the past few years, a movement to divest from the prison-industrial complex has taken off. New York State, New York City, and Philadelphia have sold their stocks in the two major corporations that operate private prisons. Columbia University became the first institution of higher education to divest, followed by the University of California system. In March, JPMorgan Chase announced that it would no longer finance the Geo Group and CoreCivic. But private-prison companies are only a small (if highly visible) part of the prison-industrial complex, and stocks only a portion of most institutional investors’ portfolios.

Divestment activists will have their work cut out for them. Mass incarceration isn’t just an ugly societal outgrowth that can be lopped off; the excision of these industries would reverberate in unexpected ways throughout the national economy, affecting not just financial firms like HIG Capital but also pensioners from Ohio to Orange County.

When I mentioned this to Alex Friedmann, he shrugged off the collateral damage. “You know,” he said, “slavery had a lot of economic benefits. A lot of people owned slaves and produced goods, and a lot of ordinary people benefited from those goods, and so on. But nobody today would say, ‘Well, we should have just reformed slavery, improved slavery, reduced it to an acceptable level.’ There is no acceptable level. And that’s my position on profiting off incarceration: There is no acceptable level. It’s inherently morally and ethically wrong.”