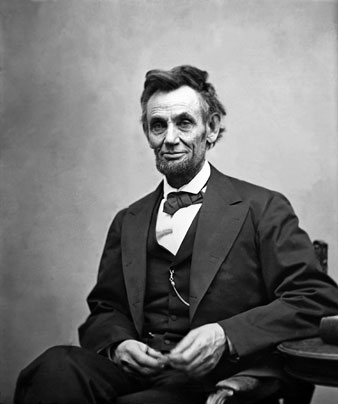

Everett CollectionAbraham Lincoln (1809-1865) seated and holding his spectacles and a pencil on Feb. 5, 1865 in portrait by Alexander Gardner.

Everett CollectionAbraham Lincoln (1809-1865) seated and holding his spectacles and a pencil on Feb. 5, 1865 in portrait by Alexander Gardner.

Abraham Lincoln has always provided a lens through which Americans examine themselves. He has been described as a consummate moralist and a shrewd political operator, a lifelong foe of slavery and an inveterate racist. Politicians from conservatives to communists, civil rights activists to segregationists, have claimed him as their own. With the approach of the bicentennial of his birth, the past few years have seen an outpouring of books on Lincoln of every size, shape and description. His psychology, marriage, law career, political practices, racial attitudes and every one of his major speeches have been subjected to minute examination.

Lincoln is important to us not because of his melancholia or how he chose his cabinet but because of his role in the vast human drama of emancipation and what his life tells us about slavery’s enduring legacy. The Nation, founded by veterans of the struggle for abolition three months after Lincoln’s death, dedicated itself to completing the unfinished task of making the former slaves equal citizens. It soon abandoned this goal, but in the twentieth century again took up the banner of racial justice. Who is our Lincoln?

In the wake of the 2008 election and an inaugural address with “a new birth of freedom,” a phrase borrowed from the Gettysburg Address, as its theme, the Lincoln we should remember is the politician whose greatness lay in his capacity for growth. Much of that growth stemmed from his complex relationship with the radicals of his day, black and white abolitionists who fought against overwhelming odds to bring the moral issue of slavery to the forefront of national life.

Until well into the Civil War, Lincoln was not an advocate of immediate abolition. But he was well aware of the abolitionists’ significance in creating public sentiment hostile to slavery. Every schoolboy, Lincoln noted in 1858, recognized the names of William Wilberforce and Granville Sharpe, leaders of the earlier struggle to outlaw the Atlantic slave trade, “but who can now name a single man who labored to retard it?” On issue after issue–abolition in the nation’s capital, wartime emancipation, enlisting black soldiers, amending the Constitution to abolish slavery, allowing some blacks to vote–Lincoln came to occupy positions the abolitionists had first staked out. The destruction of slavery during the war offers an example, as relevant today as in Lincoln’s time, of how the combination of an engaged social movement and an enlightened leader can produce progressive social change.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Unlike the abolitionists, most of whom sought to influence the political system from outside, for nearly his entire adult life Lincoln was a politician. He first ran for the Illinois Legislature at 23. Although he spoke occasionally about slavery during his early career, Lincoln did not elaborate his views until the 1850s, when he emerged as a major spokesman for the newly created Republican Party, committed to halting slavery’s westward expansion. Like Barack Obama, Lincoln came to national prominence through oratory, not a record of significant accomplishment in office. In speeches of eloquence and power, Lincoln condemned slavery as a violation of the founding principles of the United States as enunciated in the Declaration of Independence–the affirmation of human equality and of the natural right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

“I have always hated slavery,” Lincoln once declared, “I think as much as any abolitionist.” He spoke of slavery as a “monstrous injustice,” a cancer that threatened the lifeblood of the American nation. But he did not share the abolitionist conviction that the moral issue of slavery overrode all others. William Lloyd Garrison burned a copy of the Constitution because of its clauses protecting slavery. But Lincoln, as he explained in a letter to his Kentucky friend Joshua Speed, was willing to “crucify [his] feelings” out of “loyalty to the Constitution and the Union.”

Like many of his contemporaries, Lincoln believed the United States embodied the principles of democracy and self-government and should help to spread them throughout the world. This, of course, was the theme of the Gettysburg Address. He was not, to be sure, a believer in Manifest Destiny–the idea that Americans had a God-given right to acquire new territory in the name of liberty, regardless of the desires of the territory’s actual inhabitants. Lincoln saw American democracy as an example to the rest of the world, not something to be imposed by unilateral force. Slavery interfered with the fulfillment of this historic mission: it “deprives our republican example of its just influence in the world–enables the enemies of free institutions, with plausibility, to taunt us as hypocrites–causes the real friends of freedom to doubt our sincerity.” Yet, for the United States to serve as a beacon of democracy, the nation’s unity must be maintained, even if this meant compromising with slavery.

Another key difference between Lincoln and abolitionists lay in their views regarding race. Abolitionists insisted that once freed, slaves should be recognized as equal members of the Republic. They viewed the struggles against slavery and racism as intimately connected. Lincoln saw them as distinct. Unlike his Democratic opponents in the North and pro-slavery advocates in the South, Lincoln claimed for blacks the natural rights enumerated in the Declaration of Independence. But, he insisted, these did not necessarily carry with them civil, political or social equality. Persistently charged with belief in “Negro equality” during his campaign for the Senate against Stephen Douglas in 1858, Lincoln responded that he was not, “nor ever have been, in favor of making voters or jurors of Negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people.” Abolitionists worked tirelessly to repeal Northern laws that relegated blacks to second-class citizenship. Lincoln refused to condemn the notorious Black Laws of Illinois, which made it a crime for black people to enter the state.

Throughout the 1850s and for the first half of the Civil War, Lincoln believed that “colonization”–that is, encouraging black people to emigrate to a new homeland in Africa, the Caribbean or Central America–ought to accompany the end of slavery. We sometimes forget how widespread the belief in colonization was in the pre-Civil War era. Henry Clay and Thomas Jefferson, the statesmen most revered by Lincoln, outlined plans to accomplish it. Colonization allowed its proponents to think about the end of slavery without confronting the question of the place of blacks in a post-emancipation society. Some colonizationists spoke of the “degradation” of free blacks and insisted that multiplying their numbers would pose a danger to American society. Others, like Lincoln, emphasized the strength of white racism. Because of it, he said several times, blacks could never achieve equality in the United States. They should remove themselves to a homeland where they could fully enjoy freedom and self-government.

Colonization was bitterly opposed by most blacks in the North, and, after 1830, by most white abolitionists. They offered an alternative vision of America as a biracial society of equals. Through the attack on colonization, the modern idea of equality as something that knows no racial boundaries was born. At the time of his election as president, however, Lincoln was typical of the majority of Northerners, who were willing to go to war over slavery’s expansion yet thought of America as essentially a country for white people.

Lincoln shared many of the prevailing prejudices of his era. But, he insisted, there was a bedrock principle of equality that transcended race–the equal right to the fruits of one’s labor. There are many grounds for condemning the institution of slavery: moral, religious, political, economic. Lincoln referred to all of them at one time or another. But ultimately he saw slavery as a form of theft, of one person appropriating the labor of another. Using a black woman as an illustration, he explained the kind of equality in which he believed: “In some respects she certainly is not my equal; but in her natural right to eat the bread she earns with her own hands without asking leave of any one else, she is my equal, and the equal of all others.”

Shortly before the 1860 election, Frederick Douglass offered a succinct summary of the dilemma confronting opponents of slavery like Lincoln, who worked within the political system rather than outside it. Abstractly, Douglass wrote, most Northerners would agree that slavery was wrong. The challenge was to find a way of “translating antislavery sentiment into antislavery action.” The Constitution barred interference with slavery in the states where it already existed. For Lincoln, as for most Republicans, antislavery action meant not attacking slavery where it was but working to prevent slavery’s westward expansion.

Lincoln, however, did talk about a future without slavery. The aim of the Republican Party, he insisted, was to put the institution on the road to “ultimate extinction,” a phrase he borrowed from Henry Clay. Ultimate extinction could take a long time: Lincoln once said that slavery might survive for another hundred years. But to the South, Lincoln seemed as dangerous as an abolitionist, because he was committed to the eventual end of slavery. This was why his election in 1860 led inexorably to secession and civil war.

The war did not begin as a crusade to abolish slavery. Almost from the start, however, abolitionists and Radical Republicans pressed for action against the institution as a war measure. And very quickly, slavery began to disintegrate. Hundreds, then thousands, of blacks ran away to Union lines. Far from the battlefields, reports multiplied of insubordinate behavior. The actions of slaves forced the administration to begin to devise policies with regard to slavery.

Faced with this pressure, Lincoln put forward his own ideas. He first proposed gradual, voluntary emancipation coupled with monetary compensation for slaveholders and colonization of freed blacks–the traditional approach of politicians critical of slavery but unwilling to challenge the property right of slaveholders. Lincoln’s plan would make slaveowners partners in abolition. He suggested it to the four slave states that remained in the Union–Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky and Missouri–but found no takers. In mid-1862 Congress moved ahead of Lincoln on emancipation, although he signed all its measures: abolition in the territories; abolition in the District of Columbia (with around $300 compensation for each owner); the Second Confiscation Act of July 1862, which freed all slaves of pro-Confederate owners in areas henceforth occupied by the Union Army and slaves of such owners who escaped to Union lines.

Meanwhile, Lincoln was moving toward a new approach to slavery. A powerful combination of events propelled him: the failure of efforts to fight the Civil War without targeting the economic foundation of Southern society; the need to forestall threatened British recognition of the Confederacy; mounting demands in the North for abolition; and the waning of enthusiasm for military enlistment, which sparked a desire to tap the reservoir of black manpower for the military. In September 1862 Lincoln warned the South to lay down its arms or face a presidential decree abolishing slavery. On January 1, 1863, he signed the Emancipation Proclamation.

Contrary to legend, Lincoln did not free 4 million slaves with a stroke of his pen. A measure whose constitutional legitimacy rested on the “war power” of the president, the proclamation had no bearing on slaves in the four border states that remained in the Union. It also exempted certain areas of the Confederacy under Union military control. All told, the Emancipation Proclamation did not apply to perhaps 750,000 of the 4 million slaves.

Unlike the Declaration of Independence, the proclamation contains no soaring language, no immortal preamble enunciating the rights of man. Nonetheless, it marked the turning point of the Civil War and of Lincoln’s understanding of his role in history. The proclamation sounded the death knell of slavery in the United States. Everybody recognized that if slavery perished in South Carolina, Alabama and Mississippi, it could hardly survive in Kentucky, Missouri and a few parishes of Louisiana.

In his annual message to Congress of December 1862, Lincoln pointed out that crises require Americans to rethink their previous assumptions: “As our case is new, so we must think anew, and act anew. We must disenthrall ourselves, and then we shall save our country.” Lincoln included himself in that “we.” The Emancipation Proclamation was markedly different from his previous statements and policies regarding slavery. It was immediate, not gradual, contained no mention of monetary compensation for slaveowners and made no reference to colonization. Instead, it enjoined emancipated slaves to “labor faithfully for reasonable wages” in the United States. For the first time, it authorized the enrollment of black soldiers into the Union Army. The proclamation set in motion the process by which 200,000 black men in the last two years of the war fought for the Union. Putting black men into the military implied a very different vision of their future place in American society than earlier plans for settling freed slaves overseas.

Lincoln came to emancipation more slowly than the abolitionists and their Radical Republican allies desired. But having made the decision, he did not look back. In 1864, with casualties mounting, some urged him to rescind the proclamation, in which case, they believed, the South could be persuaded to return to the Union. Lincoln would not consider this. Were he to do so, he told one visitor, “I should be damned in time and eternity.” Indeed, in the last two years of the war, he pressed the border states to take action against slavery on their own, and made support of emancipation a requirement for Southerners who renounced the Confederacy and wished to have their property other than slaves restored. He worked to secure Congressional passage of the Thirteenth Amendment. This was another measure originally proposed by the abolitionists that Lincoln came to support. When ratified in 1865, it marked the irrevocable destruction of slavery throughout the United States.

Moreover, by decoupling emancipation from colonization, Lincoln in effect launched the process known as Reconstruction–the remaking of Southern society, politics and race relations. Lincoln did not live to see it implemented and eventually abandoned. But in the last two years of the war he came to recognize that if emancipation settled one question, the fate of slavery, it opened another: what was to be the role of emancipated slaves in postwar American life? The “new birth of freedom” ushered in by the war was one in which blacks for the first time would share. During Reconstruction this would entail a redefinition of American nationality–the rewriting of the laws and Constitution to embrace the abolitionist vision of a society that had advanced beyond the tyranny of race.

In 1863 and 1864, Lincoln for the first time began to think seriously of the role blacks would play in a postslavery America. In his “last speech,” delivered at the White House in April 1865 a few days before his assassination, Lincoln announced his support for limited black suffrage in the reconstructed South. He singled out as most worthy the “very intelligent”–educated blacks who had been free before the war–and “those who serve our cause as soldiers.” Hardly an unambiguous embrace of equality, this was the first time an American president had publicly endorsed any kind of political rights for blacks (this at a time when only six Northern states allowed blacks to vote). Lincoln was telling the country that the service of black soldiers entitled them to a voice in the reunited nation.

A month earlier, Lincoln had looked to the future in perhaps his greatest speech of all, the Second Inaugural Address. Today we tend to remember it for its closing words: “with malice toward none, with charity for all…let us strive to bind up the nation’s wounds.” But before that noble ending, Lincoln tried to instruct his fellow countrymen on the historical significance of the war and the unfinished task that lay ahead.

It must have been very tempting, with Union victory imminent, for Lincoln to blame the sins of the Confederacy for the war and claim the outcome as the will of God. Everybody knew, he noted, that slavery was “somehow” the cause of the war. Yet Lincoln called it “American slavery,” not Southern slavery, underscoring the entire nation’s complicity. No man, he continued, knows God’s will. God might wish the war to continue as a punishment for the sin of slavery, “until all the wealth piled by the bondman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn by the sword.” For one last time, he reiterated his definition of slavery as the theft of labor, now coupled with one of his very few public invocations of the physical brutality inherent in the institution (he generally preferred to appeal to the reason of his listeners rather than their emotions).

In essence, Lincoln was asking Americans to confront unblinkingly the legacy of bondage and to think about the requirements of justice. What is the nation’s obligation for those 250 years of unpaid labor? What is necessary to enable the former slaves, their children and their descendants to enjoy the “pursuit of happiness” he had always insisted was their natural right but that had so long been denied them? Lincoln did not live to provide an answer.

Today we inhabit an entirely different world from Lincoln’s. But the questions raised by emancipation continue to bedevil American society. The challenge confronting President Obama is to move beyond the powerful symbolism of his election as the first African-American president toward substantive actions that address the still unfinished struggle for equality.