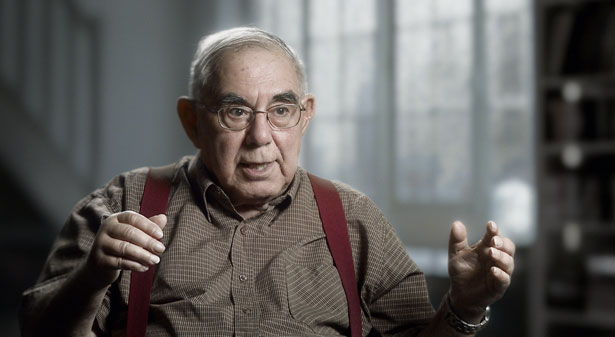

Avraham Shalom, former head of Shin Bet (courtesy Sony Pictures Classics)

Dror Moreh’s film The Gatekeepers—one of five nominated for an Academy Award in the documentary feature category—is a brilliant, deeply disturbing portrait of the post-1967 Israeli occupation. This year’s strong field of nominees also includes 5 Broken Cameras, another film about the occupation, directed by Palestinian Emad Burnat with Israeli Guy Davidi.

It’s hard to imagine two more stylistically and thematically distinct films. Burnat’s is a highly personal account of the struggle of his West Bank village, Bil’in, against Israel’s separation wall, and the accompanying army and settler destruction of its olive groves. Burnat interweaves scenes of domestic life with those of Bil’in’s weekly protests; the fact that five of his cameras were broken by the army in the course of filming is a testament both to his seemingly continuous engagement and the army’s habitually violent response to unarmed protest. 5 Broken Cameras is a moving and artfully constructed diary of family and community resistance.

The Gatekeepers, on the other hand, tells the story of occupation from the standpoint of its leading enforcers, six former heads of the General Security Service, or Shin Bet. The film is remarkable for its historical breadth and revelations from those who have run one of the country’s most secretive agencies. Never before have this many Shin Bet heads spoken on the record. From Avraham Shalom, who led the service from 1980 to 1986, to Yuval Diskin (2005–11), these men are intellectually impressive and sometimes eloquent, though at times they display a chilling ruthlessness. Moreh says he was inspired by The Fog of War, Errol Morris’s 2003 portrait of Robert McNamara, and the influence is evident. Moreh’s interviews are framed by creepy re-enactments of intelligence operations, multiple computer screens, repeated surveillance shots of assassination targets. The underlying mood, heightened by a doom-laden soundtrack and computerized simulations, is one of foreboding, conveying the sense of an impersonal, machinelike bureaucracy at work. Yaakov Peri (1988–94), who headed the Shin Bet at the height of the first intifada, says it is “a well-oiled system. It’s well organized and effective.”

Yet that mood stands in contrast to the thoughtfulness, fallibility and frequent self-criticism of the interview subjects. It was precisely that post-retirement soul-searching that inspired Moreh to make this film: as he was working on a documentary about Ariel Sharon, he learned that one of the reasons Sharon, a key architect of the settlement project, decided to withdraw settlers from Gaza was the unprecedented 2003 public protest by four of these former Shin Bet heads, who denounced his government’s single-minded focus on repression during the second intifada. As Ami Ayalon (1996–2000) put it at the time, “We are taking very sure and measured steps to a point where the State of Israel will not be a democracy or a home for the Jewish people.”

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

A key theme of The Gatekeepers is the irresponsibility of Israel’s politicians, who have avoided hard decisions and have abetted the most dangerous elements in society. As Shalom puts it, any talk of a political solution to the occupation disappeared soon after it began, to be replaced only by a tactical focus on fighting terror. “No Israeli prime minister,” he says, “took the Palestinians into consideration.” Peri observes that every Israeli government either accepted or came to accept the settlements. This gave extremists the feeling they were “becoming the masters” and could do whatever they wanted. A particularly egregious case was that of the Jewish Underground, which plotted in the 1980s to blow up the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, Islam’s third-holiest site, in the hope of triggering Armageddon and the coming of the Messiah. The Shin Bet foiled the plot at an advanced stage and the conspirators were duly tried and sentenced to prison, but because they had connections to powerful leaders in the cabinet and Knesset, they were released early. Several Shin Bet directors deplore the far right’s incitement against Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin preceding his 1995 assassination. Moreh himself, echoing the criticism of Carmi Gillon (1994–96) in the film, denounced Israel’s current prime minister in a February CNN interview with Christiane Amanpour, saying, “Benjamin Netanyahu took his big share in that.”

Avraham Shalom presents the most striking contrasts. The oldest of the six, he looks, in his suspenders and checked shirt, like a harmless old grandfather, chuckling frequently at his own jokes. Yet Diskin says he was an uncompromising bully. And when asked about the scandal that ended his career—the Bus 300 incident of 1984, in which Palestinian hijackers who were captured unharmed were murdered by the Shin Bet on his orders—Shalom is at first evasive, then admits it was “a lynching,” then bristles defensively, insisting that “with terrorism there are no morals. Find morals in terrorists first.”

Near the end of the film, though, Shalom registers one of the strongest criticisms of Israel, saying, “We’ve become cruel…to ourselves as well, but mainly to the occupied population.” Even more astounding, he likens the Israeli occupation to that of the Nazis (making a careful exception for the Holocaust itself). His fierce condemnations are echoed by the others; Ayalon refers to the “banality of evil” in warning against the speeded-up “conveyor belt” of assassinations, when “200, 300 people die because of the idea of ‘targeted assassinations.’” All these Shin Bet heads seem to have become humbled, both by what they have done (Diskin, reflecting on the assassination of terrorists, says, “What’s unnatural is the power you have” to “take their lives in an instant”) and by what Israel has become: Gillon says, “We are making the lives of millions unbearable.”

One of the most important lessons imparted by The Gatekeepers is that no matter how well trained the Shin Bet’s agents, no matter how ruthlessly these guardians carry out their tasks, without wise leadership by politicians, their mission may be fruitless in the long run. As Avi Dichter (2000–05) observes, “You can’t make peace using military means.” Ayalon closes the film with a prophetic warning: “The tragedy of Israel’s public security debate is that we don’t realize that we face a frustrating situation in which we win every battle, but we lose the war.”

If The Gatekeepers gives the perspective of the occupation’s enforcers and 5 Broken Cameras that of Palestinian civil society’s resistance, Ra’anan Alexandrowicz’s The Law in These Parts (2011) exposes the legal machinery of occupation. Like Moreh, Alexandrowicz uses archival footage to round out a set of interviews; his are with military legal advisers, prosecutors and judges. His film shows how detention without trial, systematic torture, land seizures and settlement building, house demolitions and deportations are validated by the Israeli military court system despite clear violations of the Geneva Conventions and other international laws. (For a scholarly analysis of this system, see Lisa Hajjar’s Courting Conflict, reviewed in these pages by Neve Gordon in the May 2, 2005, issue.)

From the beginning of the occupation, Israel allowed Palestinians to appeal cases to the Supreme Court, even though, according to Alexandrowicz, “international law doesn’t demand” it. Why? The point, he says, is to provide civilian oversight of military rulings by an impartial, “respected” authority. But since, as we learn, the court almost never overrules the army’s security claims, why the charade? A military judge explains: “The very fact that the Court permits a certain action, gives the action a legal seal of approval.” The court, then, far from being a hindrance to military rule, has been “convenient for the security forces.” Even on those rare occasions when the court has blocked actions, the government or military has usually found a way around it. When, for example, the court invalidated seizure of private land to build the settlement of Elon Moreh, legal advisers dug up an old Ottoman law that allowed the government to reclassify land not in immediate use as “state land” and then transfer it to settlers. Justice Meir Shamgar accepted the chicanery, a ruling that helped open the settlement floodgates. But when asked if he feels responsible, Shamgar replies, “This is a political phenomenon which is not connected to the court.”

The Law in These Parts also sheds light on the Shin Bet’s role in the legal system. When cases go to trial, military judges generally defer to Shin Bet testimony, routinely denying defendants access to evidence used against them, even though it was actually Shin Bet policy to lie in court, and—as one government commission found—from the very beginning of the occupation, torture was used to wring confessions from detainees (torture was finally declared illegal in 1999, although after the second intifada broke out, the rules were relaxed).

All of these films provide an excellent cinematic guide to the post-1967 era, but what about the Six-Day War’s antecedent? One of 2012’s most fascinating documentaries is the video testimony collected for the exhibition and research project Towards a Common Archive, a collaboration between the Israeli organization Zochrot (“Remembering”) and filmmaker Eyal Sivan and historian Ilan Pappé. This project will certainly win no awards for style, but the testimonies, by aging Jewish veterans of the 1948 war, are often mesmerizing, sometimes downright horrifying. They include matter-of-fact recollections of expulsions; routine shooting of civilians, including at least one massacre; and systematic demolition of Palestinian villages. Some of these Jewish fighters had themselves recently been refugees from Europe. One vet, talking about the sight of Palestinians in flight, says, “As a Holocaust survivor, it was traumatic for me.”

In broad outline, historians have not contested Palestinian memory of this history, at least since Israel’s “New Historians,” scholars like Pappé and Benny Morris, explored Israeli government archives in the 1980s. But as Sivan and Pappé point out in a conversation that’s part of the Common Archive, the testimonies of ground-level perpetrators are a crucial element in the history of the conflict. They not only corroborate—and give human dimension to—the archival discoveries; they undermine the common liberal claim that there are “two narratives” of the conflict, a Jewish one and a Palestinian one. For in stunning detail, these veterans echo the story of the Nakba that Palestinians have been telling for sixty-four years. Until we acknowledge the testimony of these veterans along with that of the victims, Pappé says, reconciliation will not be possible. What we can build now with these accounts, Sivan and Pappé say, is “the archive of the future…the archive of the joint state,” which doesn’t exist yet. Citing South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Pappé argues that acceptance and reconciliation must be conditioned on acknowledgment and accountability from both sides.

The alternative is continued denial and conflict—or, perhaps even worse, what Pappé sees as the growing exhaustion among Israelis at “playing the game of democracy.” After all, denial is predicated on respect for democratic norms and the feeling that some acts are shameful. With the gathering strength of the far right and ultra-Orthodox in Israel, the future of democracy is not at all guaranteed. Near the end of The Gatekeepers, Moreh cites the famed Israeli professor and prophet Yeshayahu Leibowitz, who said in 1968, “A state ruling over a hostile population…will necessarily become a Shin Bet state, with all that this implies for education, freedom of speech and thought, and democracy.” Yuval Diskin responds, “I agree with every word he wrote…. I think it’s an accurate depiction of the reality that emerged.”

Max Blumenthal explains why he sees the recent Israeli elections as a victory for the right,

despite Netanyahu’s lower-than-expected score (Jan. 23).