Last Sunday, Leslie Stahl used the coveted first segment on CBS’s 60 Minutes to do a puff-piece on the Pentagon’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. Her story, which included a minor scoop about the agency’s work on cyber security, was covered all week in the tech press and gave DARPA another opportunity to strut its stuff on the national stage.

But it was a shameful piece of self-promotion, and adds another dud to the illustrious program’s list of failures that includes a widely discredited 2013 report on Benghazi. That’s unfortunate, because 60 Minutes has historically been at the forefront of investigative reporting, as the shocking and untimely death of Bob Simon Wednesday night reminded us.

DARPA is widely known to the public as the inventor of the Internet and the developer of a long list of military products used widely in the civilian world, from drones to robots to the Siri voice on your iPhone. It’s also been a favorite topic for the national security and tech press for years because of the many dog-and-pony shows it puts on for the media. Opportunities like that can really get reporters’ blood pumping (maybe that’s why the web version of the DARPA story is sponsored by Viagra).

Stahl was just the latest to fall in DARPA’s honey trap. In her twenty-minute segment, which included interviews inside the agency’s glassed-in headquarters in Alexandria, Virginia, she carefully avoided any mention of the agency’s near-total dependence on private contractors and universities. Worse, she allowed agency officials to falsely obscure their past and their close working relationship with the National Security Agency and other elements of the surveillance state.

Her story focused on Dan Kaufman, director of DARPA’s Information Innovation Office, also known as I2O. “DARPA Dan,” as she called him, is “the man the Department of Defense has put in charge of inventing technology to fight [our] new Internet war.” Kaufman told Stahl how his agency is using artificial intelligence—particularly a search program called Memex—to help US intelligence and law enforcement agencies identify and combat human traffickers, hackers and other criminal elements that use the “dark web” to spread and exploit misery.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

The segment concluded with Stahl driving a Chevrolet Impala around a giant DARPA parking lot while an agency technician, guided by an amused Kaufman, hacked into the car’s Guidestar system to steer, stop and otherwise control the vehicle. Throughout the experience, Stahl could hardly contain herself. “I cannot—oh, my God. I can’t operate the brakes at all,” she blurted when DARPA took control. “Oh, my word. That is frightening.”

Frightening indeed. There’s no question that thwarting dangerous hackers and ending the scourge of human trafficking are righteous tasks, and it’s commendable that the Department of Defense is funding programs to unmask the organized criminals engaged in these sordid practices.

But Stahl’s piece, like too many other reports on DARPA, left the false impression of a benevolent agency doing what government does best: working behind the scenes to develop technologies that will protect American citizens, defend the nation and help the oppressed. It’s exactly the image DARPA cultivates, and why it devotes enormous efforts every week to public relations.

The problem is, it’s an extremely misleading picture. Let me count the ways.

DARPA is a feeding trough for the private sector

It’s true that DARPA is part of the Pentagon and funded by Congress—but it’s essentially run and managed by contractors. And in contrast to the 70 percent spent on contractors by most agencies, close to 100 percent of DARPA’s budget goes out to the private sector, including defense contractors (large and small) and dozens of universities scattered around the country.

One hundred percent? Yes—and that’s according to Kaufman himself. A year ago, Kevin Baron, the editor of Defense One, a Washington publication sponsored in part by Northrop Grumman, interviewed “DARPA Dan” for a live web telecast about the “DoD for the Future.” Midway through, they had this revealing exchange (Baron’s question is slightly edited; the italics are mine):

Baron: When you look at the private sector, do you see [things] that they’re doing that you think are kinda dead on?

Kaufman: Well, so first of all, right; remember everything DARPA does is actually done all through contract, so we’re not a lab. So everything we do is—is money that we give out to the private sector or to universities or other public things, so all, all the work is done out there.

In fact, DARPA was a pioneer in the use of private contractors. As I wrote in my book Spies for Hire, when US intelligence budgets and personnel rolls were slashed at the end of the Cold War, DARPA became a conduit for the first big wave of contractors to work for the NSA, the CIA and other agencies.

DARPA’s research programs marked the first “shift of people in the private sector actually doing intelligence,” William Golden, a former NSA officer who started one of the first recruitment companies for contractors, once told me. (In his first term, during those halcyon years of comparative peace, President Clinton persuaded DARPA to drop the “D” for defense; it was restored in 1996.)

Take Memex, the data-mining program highlighted by Stahl. It’s “being developed by 17 different contractor teams,” cyber expert Kim Zetter reported in Wired this week. The prime contractor for Memex is a relatively obscure company called IST Research founded by Ryan Paterson.

In classic revolving-door fashion, Paterson, now CEO of IST, spent much of his military career at DARPA and “established DARPA’s first full-time presence in an active conflict since the Vietnam War” by setting up military research programs in Iraq and Afghanistan, his official biography states (more on DARPA in Afghanistan later).

Universities also get a big piece of the Memex pie. On January 13, Carnegie Mellon University announced a three-year, $3.6 million contract from DARPA to work on the human trafficking project. It explains:

The contract is part of DARPA’s Memex program, a three-year research initiative to develop software that will enable domain-specific indexing of open, public Web content and domain-specific search capabilities. The contract is administered by the Air Force Research Laboratory in Rome, N.Y.

Other major DARPA contactors include SAIC (a major NSA contractor), Leidos (which was spun out of SAIC’s national security division, Raytheon and Data Tactics. The latter was recently acquired by L-3 Communications, another major NSA contractor that’s been in a hiring spree for students with “an interest in data analysis” for DARPA’s “annual summer camp” for the Memex program. At this agency, they like to start them young.

In its solicitations, DARPA makes it crystal clear that its work is only intended for profit-making—with one exception. “Government entities must clearly demonstrate that the proposed work is not otherwise available from the private sector,” the agency’s RFP for the Memex program states.

Again, there is nothing wrong with a government agency tapping the capabilities of leading-edge private firms, particularly in the areas of high tech. But at DARPA, the unusually close ties between the agency and its many contractors have led to almost laughable conflicts of interest that don’t seem to faze the government.

Last year, for example, the Pentagon’s Office of Inspector General reprimanded Regina Dugan, DARPA’s former director, saying that she had “essentially promoted her former defense contracting company to Pentagon colleagues in violation of the department’s ethics code while leading the agency.” Because she was gone, however, no action was taken.

Moreover, the investigation only came about because the Project for Government Oversight brought the extensive ethical problems between DARPA and its partners to the Pentagon’s attention in a detailed letter in 2011. “Dugan’s continued financial and familial relationship with [the contractor] RedXDefense raise concerns as to whether DARPA effectively prevents conflicts of interest,” POGO wrote.

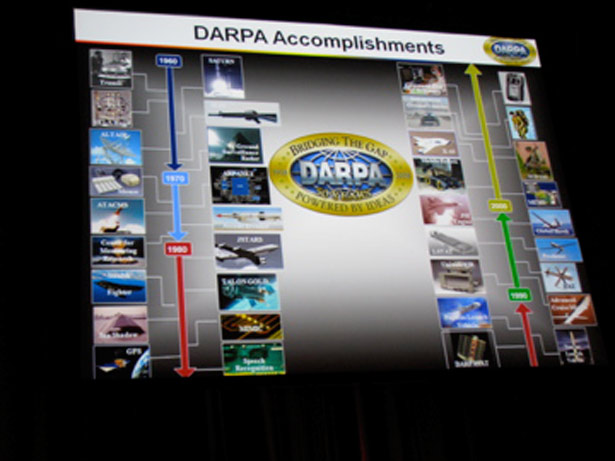

DARPA shows off inventions at GEOINT, the largest unclassified conference held by the Intelligence-Industrial Complex, 2008. (Credit: Tim Shorrock)

The real story of “DARPA DAN”

Another major flaw in the 60 Minutes story was its portrayal of Dan Kaufman. In the piece, he’s described as having magically dropped into DoD from the California gaming industry, where he worked for years (one of his products was Spongebob Squarepants). Here’s how the 60 Minutes transcript reads:

Stahl: Before DARPA, Kaufman made a fortune running several cutting-edge videogame companies. His only military experience is make-belief. He helped invent the popular war-game series “Medal Of Honor.”

Kaufman: And then 9/11 happened. And it shocked me to my soul. And I thought, “I’ve lived incredibly well off this country and I want to give something back.” But I have no idea how to work for the government. I mean, I had never thought about it. I’d never been to Washington, D.C. And I did what all nerds do. I went to Barnes and Noble. And I got a big book. It said “Government Jobs.” It was a big book. And I thumbed through it. And I said, “I will find something and I will donate some time.” And I decided I would hunt serial killers…

Nice story, Dan; but apparently Stahl’s research skills are pretty thin. Kaufman is actually part of the Silicon Valley intelligence mafia that’s been working with the CIA since the 1990s to fund companies that can produce products for surveillance and other uses.

Ever hear of In-Q-Tel? It’s the venture capital firm founded by the CIA during the Clinton administration to finance small and emerging companies with spying capabilities. Just before he came to DARPA, Kaufman represented In-Q-Tel for a spooky company called Auratio Consulting (try finding it on Google). And long before 9/11, he had close business relationship with Gilman Louie, In-Q-Tel’s first CEO (he was hired by George Tenet).

Louie, too, got his start in the gaming industry, and among his first investments were two companies called Spectrum Holobyte and Microprose. According to The Agile Mind, a blog published by technology writer Anne Laurent, Kaufman helped finance a buyout and merger of the two companies in the late 1990s. At the time, he was working for Brobeck, Phleger & Harrison, a Palo Alto, CA, law firm (since bankrupt), where he had “the largest game company representation in the United States.”

The law firm also happened to be a major player with In-Q-Tel. In August 2001, for instance, it helped engineer In-Q-Tel’s investment in a wireless sensor company called Graviton. And in his article on Kaufman’s time with Brobeck Phleger, Laurent concludes with this: “Oh, and the CIA’s venture catalyst In-Q-Tel once commissioned him to look into how gaming could help the CIA train, too.” Unless Kaufman defines the CIA’s fund as a private company, his “experience” with government goes way back before the attacks of September 11, 2001.

Yes, DARPA works with the NSA

But perhaps Kaufman’s the most egregious misrepresentation in his interview with Stahl is his response to this question:

Stahl: How much of your time is spent inventing things for the NSA?

Kaufman: Almost none, actually.

Stahl: Because a lot of this stuff could be used by them.

Kaufman: Yes.

“Almost none”? Please; that’s really splitting hairs. DARPA has long been a source of important research for the NSA and its massive surveillance programs, and data-mining programs such as Memex are eagerly sought by the NSA to deepen its abilities to find and search for national security risks and help the military and the CIA target potential or proven terrorists.

Take Chris White, whom Stahl identifies as the man who “invented Memix.” In his official biography, he’s also described as the creator of “DARPA’s leading program in big data, XDATA, which is part of the President’s Big Data Initiative.” Yes, it is; XDATA is also relied on extensively by the NSA in its surveillance programs, according to contract documents I’ve obtained about SAIC, one of DARPA’s prime contractors on XDATA.

In one of its XDATA proposals to DARPA, SAIC notes that its model “for the framework will be our prior experience in DARPA/IARPA Research and Development Experimental Collaboration (RDEC) program, which introduced a model for building a comprehensive, structured yet flexible framework for evaluation.”

IARPA is the intelligence equivalent of DARPA and develops “analytical programs” for NSA. IARPA’s website describes its relationship to the NSA in detail. And one of Kaufman’s I2O’s recent solicitations seeks research in “game-changing technologies” in various domains, including “cyber and other types of irregular warfare.”

The latter is another DARPA specialty. At the height of President Obama’s counterinsurgency war in Afghanistan in 2011, according to documents I’ve seen, DARPA’s XDATA program was part of a surveillance net supported by NSA that was used by US forces and contractors to identify and hunt down the Taliban and other groups fighting the central government. White was part of that effort, and was later recognized with a “Joint Meritorious Unit Award for support in a combat environment” by then–Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta.

Maybe Leslie Stahl should start again. I’d be happy to help with her research.