For 33 years, Edward Gorey rented an apartment in Manhattan. The author and artist hated New York City, but like so many others, he had moved there after college to embark on a career. The one-room apartment, at 36 East 38th Street, was Gorey’s refuge, his “cabinet of wonders, bohemian atelier, and Fortress of Solitude rolled into one,” as the cultural critic Mark Dery puts it in his new biography, Born to Be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey. The place was crammed with books, art, and miscellaneous objects that Gorey had collected, often memento mori. These included a real mummy’s head, which, by the time Gorey lost his lease in 1986, was sitting on a shelf in a closet, wrapped in brown paper. When he was away in Cape Cod, as the story goes, Gorey asked some friends to pack up his things for him, but they managed to miss the head. Instead, the super found it.

“I got a call from a detective at some precinct or other who said, ‘Mr. Gorey, we’ve discovered a head in your closet,’” the artist recalled in an interview. Gorey responded, “Oh, for God’s sake, can’t you tell a mummy’s head when you see one? It’s thousands of years old! Good grief! Did you think it took place over the weekend?”

In the end, the police told Gorey that he could have it back, but Gorey never received it—“not that I’m really desperate to get it back,” he added.

This anecdote reads like one of Gorey’s stories. For some reason or other, a person owns a mummy’s head because, in Gorey’s world, we are all on intimate terms with death. He might lose track or possession of it when chance circumstances intervene. But in the end, the person doesn’t really mind that the head is gone. Life goes on, until one day it doesn’t, at which point the person and the mummy become much the same.

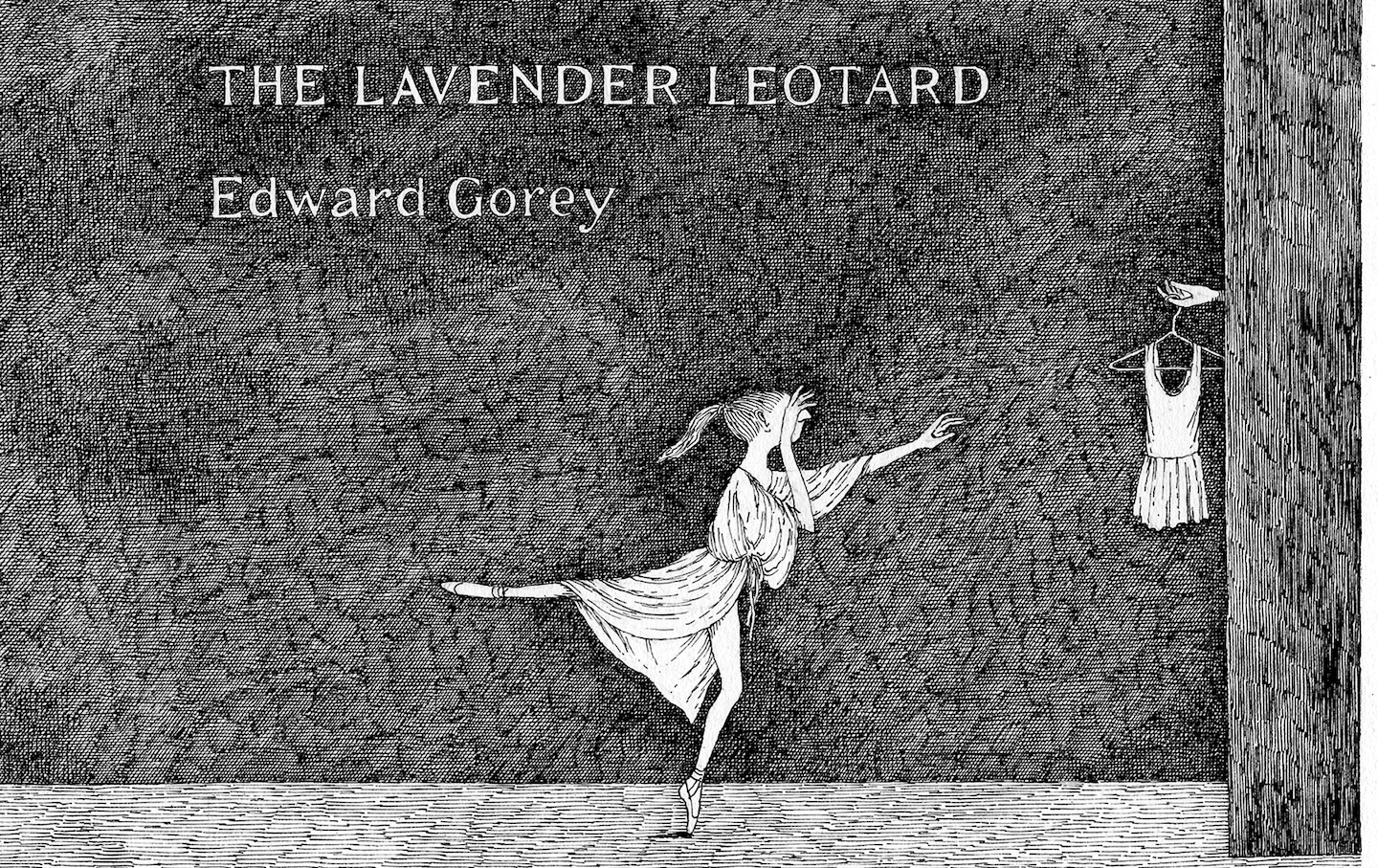

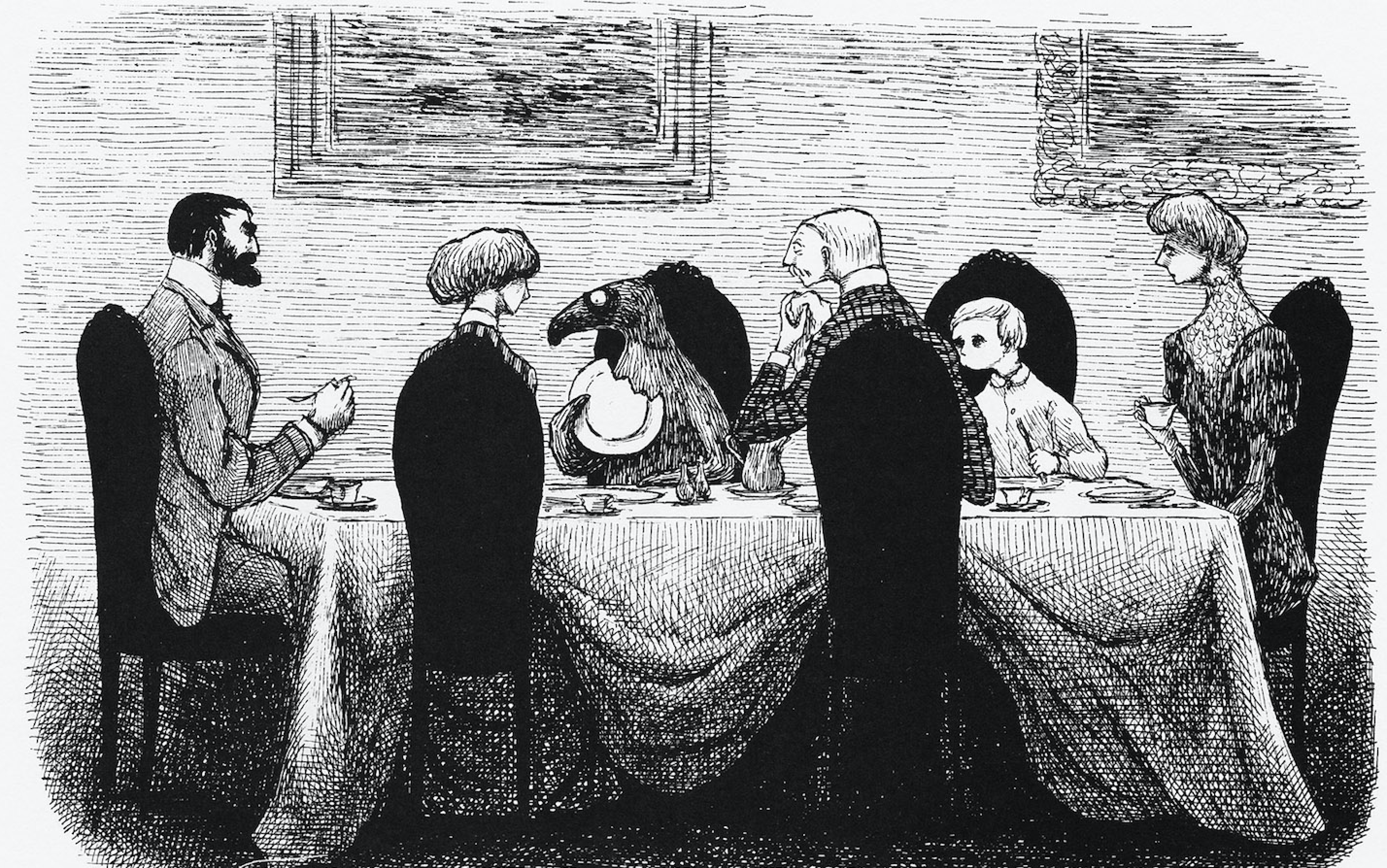

Published 18 years after his death, Born to Be Posthumous is the first full-length biography of Gorey. (His friend Alexander Theroux released a shorter, more intimate portrait, which he later expanded, in 2000.) Coming in at just over 500 pages, the book meticulously tells the story of the unconventional author and artist, who amassed an ardent following yet remains unknown to many readers. The fact that Gorey’s work is either fiercely beloved or completely unfamiliar has to do with the type of work it is: His primary output was small volumes that are reminiscent of children’s books in form but tell mostly adult tales of melancholy, mystery, and often sudden death—especially the deaths of children. “Tales” may be too strong a word in some cases, even when the contents cohere; sometimes they’re just collections of limericks or rhyming couplets of assorted words. As an adherent of literary nonsense and surrealism, Gorey was less interested in plot than tone, which he created in part through black-and-white drawings that look like prints.

As Dery sums it up, Gorey’s creations “refuse to be categorized. What are they, exactly? Picture books for grown-ups? Precursors of the graphic novel? Mash-ups of Victorian literature, the comic strip, and the silent-movie storyboard?” The volumes are, in fact, so compellingly original that, in the process of reading them, their referents merge into a tone and aesthetic of casual, impending doom that’s been dubbed “Goreyesque.” Dery’s ability to reverse the effect and break down Gorey’s many influences is one of the most valuable aspects of Born to Be Posthumous, which is as much an analysis of its subject’s work as it is a telling of his life.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

At the same time, Gorey may also linger in obscurity because he was an intensely private person. He had friends, but he seems to have kept a measure of emotional distance from everyone. “I feel that he was somehow unable and/or unwilling to engage in a very close friendship with anyone, above a certain good-humored, fun-loving level,” the poet John Ashbery, who knew Gorey at Harvard, told Dery. Nor did he have any long-term romantic relationships; “I am fortunate in that I am apparently reasonably undersexed or something,” he once said. Gorey has at times been labeled a recluse, but it seems more accurate to say that he was a loner who experienced the world by proxy, through the culture that he so voraciously consumed and produced. “[H]e lived much of his life on the page, in the worlds he conjured up with pen and ink, and did most of his adventuring between his ears,” Dery writes. “In large part, the art is the life.”

Born in Chicago in 1925, Edward St. John Gorey (nicknamed Ted) was an only child and a prodigy: He claimed to have started drawing at age 1½ and reading two years later. By the time he was 8, he’d made it through Dracula, Frankenstein, Lewis Carroll’s Alice books, and the collected works of Victor Hugo. He entered high school at 13, enrolling at the private, progressive Francis W. Parker School, where he had an inspiring art teacher and befriended future Abstract Expressionist painter Joan Mitchell (as one might guess, the two got along well but had diametrically opposed ideas of art). He honed his talents by drawing cartoons, designing sets and costumes for the senior play, and art directing the yearbook; he also refined his tastes, attending the ballet, theater, and classical-music concerts in the city.

Gorey was accepted to Harvard with a scholarship, but before he could go, he was drafted into the Army. He spent almost two years at the Dugway Proving Ground, a biological- and chemical-weapons testing facility that would become notorious in 1968, when thousands of sheep turned up sick or dead nearby. While at Dugway, Gorey wrote plays that, although they were affected, artificial, and over-the-top, introduced many of the core themes of his work: mortality, death, children as both victims and perpetrators, and melancholia. (Notably, they also feature gay characters and overt references to homosexuality.) He hadn’t yet found his form or even his voice, but he had hit upon his subject matter.

When he got to Harvard in 1946, Gorey befriended a group of mostly gay men, chief among them the poet Frank O’Hara, with whom he “formed a two-man counterculture” against the strait-laced (and predominantly straight) environment of the school at that time. The two became suitemates and installed an old tombstone to serve as their coffee table. They read and worshipped the early-20th-century gay English novelist Ronald Firbank, who relished dialogue over plot—to the point where his books are largely series of conversations—and was known for his wit, eccentricity, and sometimes perversity. (A 1969 New York Review of Books piece called him “the most fantastic of all English dandies and decadents.”) Firbank in turn influenced Ivy Compton-Burnett, another Gorey and O’Hara favorite, who also used dialogue as a primary vehicle to tell stories of dysfunctional upper-class families.

Fittingly, Gorey began to develop his signature, flamboyant fashion style around this time: a bushy beard, sneakers, rings, jewelry, and a flowing coat (in New York he would wear long fur coats that were sometimes dyed bright colors). Although he majored in French, he continued to write and make art: starting a novel, experimenting with limericks (some of which were early versions of those in his second book, The Listing Attic), and exhibiting watercolors. He even submitted his drawings to The New Yorker, which rejected them in a letter that is almost Goreyesque in its deadpan tone: “The people in your pictures are too strange and the ideas, we think, are not funny…. By way of suggestion may I say that drawings of a less eccentric nature might find a more enthusiastic audience here.” Gorey’s work would appear on the cover of the magazine 42 years later, in 1992 (one month after The New Yorker ran a profile of him), though it represents his quirkier, more family-friendly late style rather than his much weirder and darker early work.

Gorey remained in Boston after graduation, living with a former professor, the poet John Ciardi. At Harvard, Ciardi had encouraged his darkly comic limericks, which mocked the moralizing nature of most children’s literature at the time. Ciardi also helped him land his first book-illustration gig by connecting him with a psychiatrist and writer, for whom Gorey drew a series of pictures showing a personified sick sonnet visiting the doctor (both of them squat, bald, long-faced men). Gorey also collaborated with the experimental Poets’ Theatre during this period, designing everything from its logo to the promotional materials to the sets, as well as writing two plays. His involvement foreshadowed his embrace of the theater later in life, after he moved to Cape Cod, where he’d been visiting his cousins for years.

In 1952, thanks to a classmate who knew his talents, Gorey was offered a job in New York at Anchor Books. A new imprint, Anchor aimed to use the inexpensive paperback format to make modern classics more accessible to the public. Gorey worked as an artist and designer, creating covers for books by Henry James (whose work he loathed for its wordiness), Herman Melville, Joseph Conrad, and many others. The Anchor job birthed the hand lettering that looks like a softened version of print and would become a staple of Gorey’s own books; he began doing it because he lacked a traditional designer’s knowledge of typefaces. As Dery points out, some of Gorey’s “psychological motifs” are evident, too: In many of his cover designs, a figure stands alone, either alienated from those around him or dwarfed by a landscape.

Dery devotes ample space to Gorey’s underappreciated commercial work, and rightfully so. But something more important happened not long after the move to New York: In 1953, Duell, Sloan and Pearce published the first small book of Gorey’s own making, The Unstrung Harp; or, Mr Earbrass Writes a Novel, a funny and moody meditation on the painful process of writing. At 60 pages (long by future Gorey standards) and with a fairly straightforward story (also by Gorey standards), The Unstrung Harp perhaps comes the closest in his oeuvre to conventionality. Still, it inaugurates the distinct format that Gorey would use for most of his 80-plus books: text and image appearing in poised symbiosis, each a distinct entity but always working in tandem to create an imaginative space for the reader to fill. In one of my favorite spreads, we see Mr. Earbrass standing in the kitchen, reading his manuscript; in one hand, he holds a sandwich. The accompanying text reads: “The jelly in his sandwich is about to get all over his fingers.”

The Unstrung Harp introduced “the Gorey Voice,” which Dery perceptively describes as:

[A] deadpan that never cracks, but with a droll undertow; the distance between its sublime indifference and the lugubrious or odious or horrendous nature of the events it recounts is what makes for irony, and irony is what turns tragedy into black comedy in Gorey’s world.

The book also allowed for a full blossoming of his visual style: intricately hatched and crosshatched drawings of vaguely Victorian or Edwardian scenes that make ample use of light and dark to impart a kind of omnipresent ominous air, or at least a sense of unease. That air infuses the majority of Gorey’s work, including 1961’s The Hapless Child, in which Charlotte Sophia is orphaned, kidnapped, and then accidentally killed by her father, who is alive after all, and 1963’s The Gashlycrumb Tinies, perhaps Gorey’s most famous book, which is an abecedarium enumerating the deaths of various children (“N is for Neville who died of ennui”).

As Neville’s death suggests, sometimes the mood in Gorey’s work is closer to existential melancholy, as in 1958’s The Object-Lesson, an exquisite corpse of a text that, beginning with a lord’s search for his artificial leg, strings together disparate narrative fragments with a surrealist sort of dream logic. For example, one line reads, “On the shore a bat, or possibly an umbrella, disengaged itself from the shrubbery, causing those nearby to recollect the miseries of childhood,” which is perhaps the perfect encapsulation of Gorey’s talent for hovering poetically between absurdity and profundity.

Part of the eeriness of Gorey’s work is that it seems to unfold in a setting which, although based in history, feels somehow outside of time. This may reflect Gorey’s own remove from the world around him—his lack of close relationships and strenuously maintained disconnect from current events. Yet Dery helpfully contextualizes Gorey, at least in his formative years, discussing the Great Depression, the Lindbergh-baby kidnapping, and the revolution in children’s literature spurred by Dr. Seuss and Maurice Sendak to help explain his nonchalant approach to darkness. He also quotes the writer Alison Lurie, a longtime friend of Gorey’s, who sees his work as “sort of in reaction to this 1950s mystique…that everything was just wonderful and we lived forever and the sun was shining.”

Dery delves as well into Gorey’s worship of one of the most influential figures in the history of ballet, the choreographer George Balanchine, who was known for creating a neoclassical style that emphasized traditional ballet techniques and form while stripping away theatrical trappings, like elaborate sets and plots. Gorey called Balanchine “the great, important figure in my life…. sort of like God,” and between 1956 and 1979, he attended almost every single performance of the New York City Ballet, which Balanchine co-founded and led as the company’s artistic director for 35 years.

Gorey’s books did not sell well when they were first published; few people knew what to make of them. But those who did were hooked: Sendak compared Gorey with Mozart, and Edmund Wilson wrote an insightful essay about him in The New Yorker (“he has been working perversely to please himself and has created a whole personal world, amusing and somber, nostalgic and claustrophobic, at the same time poetic and poisoned”). But fame and commercial success came slowly—and when they arrived, it was largely due to the efforts of Andreas Brown, the proprietor of the Gotham Book Mart, a vital landmark and gathering place for New York City’s literary community for almost a century. Brown not only published some of Gorey’s books but had the idea for the collected Amphigorey volumes; he also mounted exhibitions of Gorey’s art and essentially turned him into a brand, creating Gorey calendars, jewelry, and other merchandise. (Notably, Brown would not sit down for an interview with Dery for this book.)

Gorey moved further into the mainstream—and financial security—thanks to a 1977 Broadway production of Dracula featuring his sets. He “was anointed a demicelebrity” by the media, Dery writes, and his work was adapted for the stage (the musical revue Gorey Stories) and for television (the animated opening credits for PBS’s Mystery!). And then he left it all behind: After Balanchine died in 1983, the seasonal spell of the New York City Ballet was broken, and Gorey began the process of moving to Cape Cod.

He spent the final 14 years of his life in a 19th-century house in Yarmouth Port—one that, despite the interior renovations he’d made, looked derelict from the outside. (His cousin says the artist “was attracted by the unkempt yard and air of genteel decay.”) Gorey cohabitated with his cats and surrounded himself with his collections—of art, books, rocks, rusting metal objects, salt-and-pepper shakers, stuffed animals—which he arranged and rearranged in what Dery calls “an evolving work of installation art…for an audience of one.” He also watched television obsessively—Golden Girls, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, All My Children—and sewed little rice-filled dolls.

Gorey still made books that were experimental in their own way, but they lacked the intricacy of his earlier, better work—“the spiderweb delicacy of his classic style,” as Dery puts it. Mostly, he indulged his ever-growing passion for theater by mounting amateur, often nonsensical productions that were far more experimental than one would expect at the local Cape Cod playhouses. As in his books, the action in his plays was usually a series of non sequiturs, and he insisted, “There is no motivation, just read the lines.” At the same time, he would try to extract more feeling from inanimate objects. One actor recalled him directing another, who was puppeteering a clothespin, saying, “I want to see this clothespin emote.”

Dery’s book is filled with many such delightful stories and snippets. Along with the context that he lays out for Gorey’s work, such details make Born to Be Posthumous an engrossing read despite its flaws, which include a fondness for cliché and over-the-top language, as well as an overreach on Dery’s part when it comes to Gorey’s sexuality. (This has also been a point of contention for other critics, who have objected to Dery’s treatment of it as an unsolvable, trauma-induced mystery, rather than taking Gorey at his own word that he simply wasn’t that much interested in sex.)

The vignettes are valuable not just as entertaining stories, but also because they extend the reach of Gorey’s transfixing spell. He was self-actualized in a way that most of us can only dream of: He lived how he wanted and made the work that called to him. “More and more, I think you should have absolutely no expectations and do everything for its own sake,” he once said. “That way you won’t be hit in the head quite so frequently.”

That could be read as an expression of hedonism, but I think for Gorey it was simply a statement of his commitment to the integrity of his vision, which extended to everything in his life—his creative work, his collections, his cats, his clothing. In the end, Dery’s accumulation of details disproves the thesis that he proposes early on, that Gorey’s art was his life. In truth, it seems to be the other way around: Gorey’s entire life was his art.