Do as I Say, Not as I Do

The comforting lessons in good will and friendship Apple, Netflix, and Disney flaunt are benign distractions that deflect attention from their two-fisted business behavior.

Call me old-fashioned, but swimming in the warm bath of feel-good TV, I have to wonder: Do the entertainment giants practice what they preach? Take Shape Island, a new kids’ show featuring a circle, triangle, and square, streaming on Apple TV. The New York Times described it as “a charming animated series [that] teaches young kids about friendship.” Is friendship high on the agenda of Apple TV’s parent, the hardware giant sitting atop an Everest of cash? Apple would apparently like us to think so.

Shape Island isn’t the only show on Apple TV that flaunts its feel-good vibes. Indeed, many of the other virtues—kindness, humility, diligence, et al.—are served up in Ted Lasso, the series that put Apple TV on the map. Its eponymous hero, a fish-out-water soccer coach, is so friendly he might make Mr. Rogers blush with embarrassment. Bill Lawrence, an executive producer on the show, called it “a sunshine enema.” Ted is such a paragon of positive thinking that he is emboldened to say things like “I believe in hope.” In case hope fails, he falls back on “I believe in believe.”

Apple, on the other hand, believes in profits. Forget the alleged copyright infringements that have jeopardized its latest line of smart watches. Apple’s pursuit of profits has led it to China, the world’s biggest movie market that is not only a honey pot of potential ticket-buyers to the tune of $40 billion a year, but a key cog in its supply chain, manufacturing iPhones. Consequently, as the New York Times revealed two years ago, the company “shares customer data with the Chinese government… proactively removes apps to placate Chinese officials… [and] banned apps from a Communist Party critic.” When China conducted military drills to protest House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan in the summer of 2022, Apple alerted its suppliers there to label parts, “Made in Taiwan, China.” Business Insider reported that Apple knew one of its Chinese-based suppliers was using child labor, but three years elapsed before it finally cut its ties. (Apple has denied and/or disputed some of these reports.)

In November, 2023, Apple cancelled Jon Stewart’s show, reportedly because of his critical remarks about China. As a leading TV executive was recently quoted as saying, “If someone has something to say that’s controversial, and it’s going to affect the sale of iPhones, you can be sure it’s not going to get said.”

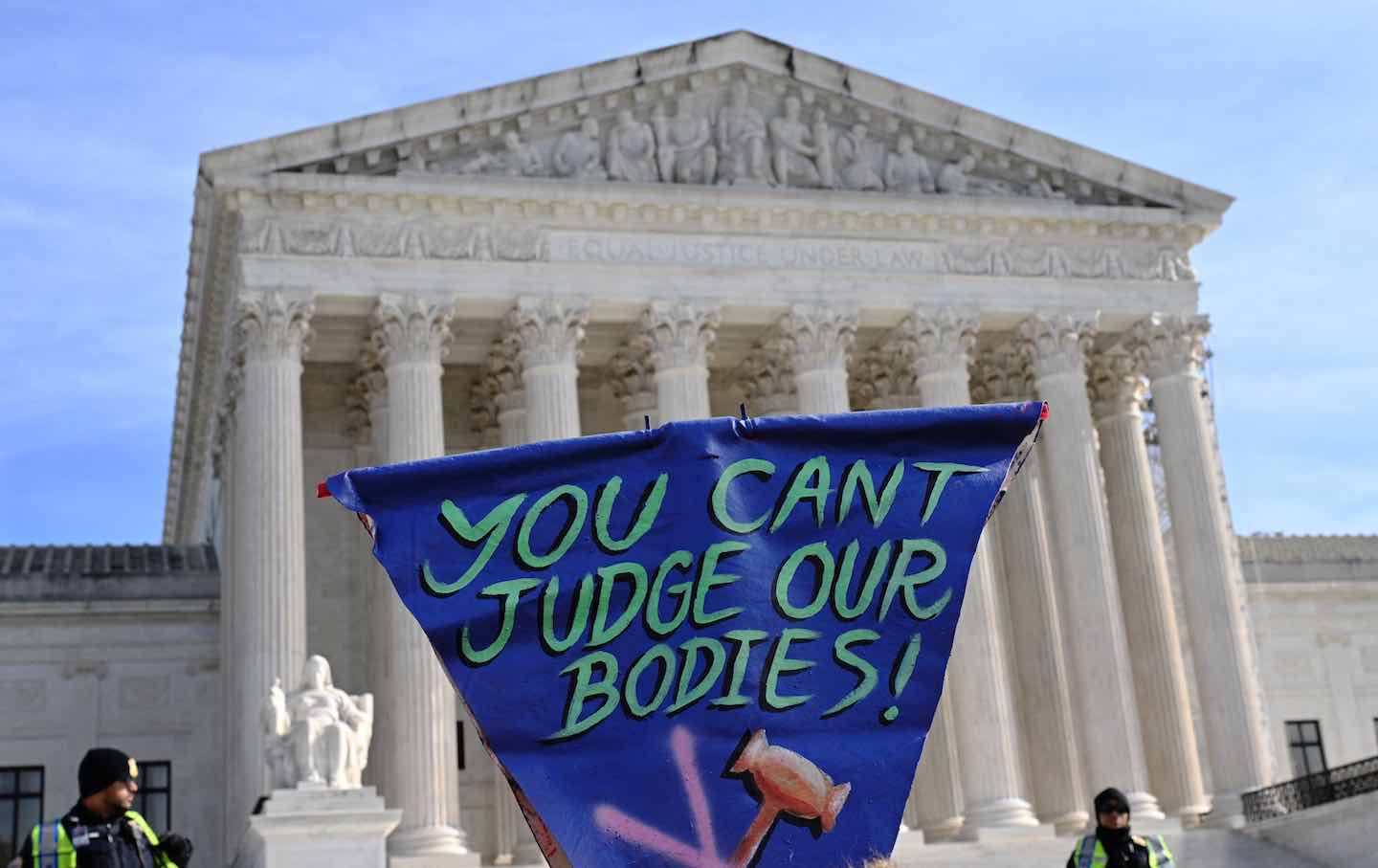

Domestically, Apple’s China is Texas. It is one of the state’s largest employers, with 7,000 workers making MacBook Pro’s in Austin, but it failed to take a stand against Governor Greg Abbot’s crusade against abortion which, according to the Times, has contributed to unprecedented “unrest” among its employees who have also complained about “verbal abuse, sexual harassment, retaliation and discrimination at work.” Apple’s fetish for secrecy prevents them from airing these issues with the company or even one another. Apparently it’s circles, triangles, and squares can’t talk to one another.

Disney’s relationship to China is just as fraught as Apple’s. CEO Bob Iger managed to talk the Chinese into allowing Disney to open two theme parks there, one in Shanghai and one in Hong Kong, but the government has a history of closing its theaters and therefore its multi-billion dollar market to Hollywood movies going back at least to 1997, when it banned Martin Scorsese’s Kundun,which it deemed too sympathetic to Tibet—and when it subsequently banned Brad Pitt’s Seven Years in Tibet,as well as Deadpool, Black Widow, Nomandland, and others for their political indiscretions. With regard to Kundun, Iger’s predecessor, Michael Eisner, was all too willing to eat crow before China’s mandarins: “The bad news is that the film was made; the good news is that nobody watched it. Here I want to apologize, and in the future we should prevent this sort of thing, which insults our friends, from happening.”

Iger, showing considerably more finesse than Eisner, kept his tongue from licking the boot by adding a Chinese plot line to Iron Man 3, shot in Beijing, that was missing from the US version. When Chinese censors deemed The Ancient One in the Doctor Strange comic too Tibetan, he was anglicized in the movie version, although ploys like that didn’t always work. Disney’s Marvel films have always been at the mercy of Sino-American relations, as China opened its market to some, but not to others.

A political liberal, Iger thought about running for president against Trump in 2016. He has embraced “positive messaging,” aka, political correctness, aerating Disney oldies with whiffs of diversity. The live-action remake of The Little Mermaid features a black actress, Halle Bailey, as Ariel, and the live-action remake of Snow White will feature Rachel Zegler, a Latina actress, in the title role. (Over at Disney’s Marvel, last year’s female-filled The Marvels bombed, becoming its worst-grossing superhero movie yet.) When The Little Mermaid flopped in China, some attributed it to Chinese racism, while others more generously explained that “political correctness” doesn’t resonate there, and still others argued that it was a reflection of resentment over the American inclination to blame China for Covid.

Politically, Iger is a contradictory figure. Despite his liberal leanings, during the pandemic he was excoriated by Abigail Disney, the granddaughter of Walt’s brother Roy O., and the daughter of O.’s son Roy E., long a thorn in her family’s corporate side. She attacked Disney’s leadership for its shabby treatment of its approximately 223,000 employees during the pandemic when it closed its parks. “Let’s not pretend that [they] go somewhere and disappear,” she wrote, quoting multiple park employees complaining that they had to “forage for food in other people’s garbage.”

The magnitude of the layoffs, eventually amounting to about thirty-two thousand employees by April 2020, caused her to take to Twitter and tweet, “WHAT THE ACTUAL F***???,” calling Iger’s extravagant 2018 salary of $65.6 million, and 2019 salary of $47.5 million “insane” and “a naked indecency.” She asked, “What kind of a person feels comfortable with that?”

Today, Iger’s base compensation is performance-based, and reduced to $1 million a year, a dramatic drop, particularly when compared to Apple’s Tim Cook, whose total compensation of $99.4 million a year is 1,777 times the median salary of his employees. (Cook’s take-home is set to drop by 40 percent in 2024.)

Disney is also famous for fiercely guarding its copyrights, quick to sue fans for infringing them by making unlicensed art or merchandise that includes any of its beloved characters. Even tattoo artists have been held liable, all of which is ironic, given that Disney grew rich monetizing “Sleeping Beauty” and other fairytales in the public domain.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The company has also been charged by nine women with discriminating against 9,000 female employees by paying them less than their male colleagues, which Disney denies. According to one employee, a female producer was taken to lunch and advised to be more “lady-like.” Adds another source, men were given more latitude than women in terms of behavior. “There was one creator there who had a restraining order against him for harassing younger female employees. He was not allowed on the lot, and yet they did not let him go. They created an entire system around him, bringing in another co-showrunner so that he could give the notes to that person who would interact with staff.” Would a woman in the same position with, say, an abusive temper, be given the same consideration? Replies a former employee, “No. I would consider that a double standard.”

Most recently, in January, the Los Angeles Times reported that another female employee is suing Disney for failing to investigate an executive whom she alleges drugged and sexually abused her.

Iger was also stung by criticism for his unfortunate choice of words to striking actors and writers when he dismissed their demands as “not realistic,” while at Allen & Company’s Sun Valley billionaire summer camp, yet. As one source put it, “Disney is not a nice company.”

Iger, on the other hand, should be credited with taking a firm stand against Florida governor Ron DeSantis, but as a result, his right-wing enemies have been quick to attack him for harming the brand, attributing Disney’s poor performance in 2023 to his liberal politics, and tagging it with the euphonious phrase, “go woke, go broke.” One poll ranked Disney number five on a list of polarizing companies, not where “the happiest place on Earth” wants to be. It didn’t take long for Iger, also under pressure from hostile board members, to backtrack. “We have to entertain first,” he said. “It’s not about the message.”

Apple and Disney are by no means the only companies in the entertainment business to say one thing and do another. Reed Hastings built Netflix by celebrating values like openness, candor, and diversity, but quickly lowered the flag when Saudi Arabia pressured him to withdraw an episode of a series called Patriot Act that included some not-so-nice things about Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, widely alleged to have ordered the dismemberment of dissident journalist Jamal Khashoggi. “We’re not trying to do truth to power,” he airily asserted. “We’re trying to entertain.” (Hastings did go on to point out that Netflix retained the offending episode on YouTube.)

Netflix produced a chunk of its shows in the state of Georgia, attracted by its climate and tax breaks. There, however, the streamer’s commitment to diversity hit a wall called “voter suppression.” Instead of boycotting the state, Netflix equivocated. As of July 2021, it had five shows shooting in Georgia, including two of its biggest series, Stranger Things and Ozark, that the company allegedly requested the Georgia film office omit from its list of active productions.

It’s true that as Shape Island teaches us, it might be nice if kids stopped biting one another because triangles, circles, and squares get along famously, but aside from giving parents what they want to hear, so far as Apple goes, it’s merely performative. Just as the Marvel movies serve as promotions for its branded watches, backpacks, spider-bots and other products that bring in more money than all its filmed entertainment combined, so the feel-good series from companies like Netflix, Apple, and Disneyare advertisements for themselves. They are important because the comforting lessons in good will and friendship they flaunt are benign distractions, shiny baubles meant in part to deflect attention from their two-fisted business behavior. If the means they employ to make their money aren’t all that friendly, they hope their audiences won’t notice.

So do the entertainment giants practice what they preach? Do what they say? Of course not. Dumb question.

More from The Nation

What Comes After the Apocalypse? A Q&A With Joshua Oppenheimer What Comes After the Apocalypse? A Q&A With Joshua Oppenheimer

Oppenheimer’s latest film, The End, is a Golden Age, postapocalyptic musical crying out from the depths of the earth.

What Luigi Mangione and Daniel Penny Are Telling Us About America What Luigi Mangione and Daniel Penny Are Telling Us About America

When social structures corrode, as they are doing now, they trigger desperate deeds like Mangione’s, and rightist vigilantes like Penny.

Donald Trump Is the Authentic American Berserk Donald Trump Is the Authentic American Berserk

Far from being an alien interloper, the incoming president draws from homegrown authoritarianism.

Banning Trans Health Care Puts Young People at Risk of Harm Banning Trans Health Care Puts Young People at Risk of Harm

Contrary to what conservative lawmakers argue, the Supreme Court will increase risks by upholding state bans on gender-affirming care.