Nilofar Ganjaie often has to ask people what belongings they can sell to help pay for their abortions. Her organization, the Northwest Abortion Access Fund (NWAAF), helps people in Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Alaska who are struggling to afford the hundreds or, later in pregnancy, thousands of dollars that an abortion costs. Each week, the fund sets aside a portion of its budget to help those with upcoming appointments. And each week, generally by Wednesday, the money is gone. So volunteers like Ganjaie walk callers through a set of calculations: Are there friends or relatives they can ask for money? Expenses they can delay? Callers have sold their clothing or children’s toys. She offers patients the option of delaying their appointments, but even then, the fund can’t guarantee help. “Those are just the most heartbreaking conversations, to walk people through options that include staying pregnant longer than they want to be,” she said.

So when her counterparts in New York City made history in June by pushing it to become the first city in the United States to directly fund abortions, Ganjaie was thrilled. The city allocated $250,000 to the New York Abortion Access Fund (NYAAF), doubling its capacity to fund abortions. She knew an amount like that would be a game changer for her own fund, which has granted roughly $300,000 this year. Before she could tell her fellow board members the news, they were already messaging on Signal. “Let’s do this,” one wrote.

A few weeks later, Ganjaie attended an event at a women’s coworking space where her congresswoman, Pramila Jayapal (D-WA), spoke to the crowd about her abortion. When Jayapal took questions, Ganjaie raised an issue that has been the third rail of abortion politics for decades: How could activists secure public funding for abortions? Jayapal, part of a newly elected wave of progressive women of color in Congress, was fresh off a failed attempt to repeal the Hyde Amendment, a ban on most federal funding for abortion that Congress has renewed every year since 1976. A group of progressive women, including Jayapal and Representative Ayanna Pressley (D-MA), had attached an amendment repealing Hyde to a budget bill, but fellow Democrats in the House Rules Committee had scuttled it. Sensing defeat, Jayapal had conceded to Roll Call that Hyde was still a “politically difficult issue.” But she seemed to think Ganjaie might have better luck locally, encouraging her to take the issue to the Seattle City Council.

Ganjaie and her colleagues plan to do just that—and they’re not alone. In September abortion fund activists in Austin, Texas, pushed the city to give $150,000 to help residents with the travel, housing, and child care costs associated with abortion. The California abortion fund Access Women’s Health Justice told The Nation that it’s contemplating similar initiatives in Los Angeles and San Francisco. At the federal level, the All Above All campaign has inspired members of Congress and a number of the 2020 Democratic presidential candidates to challenge the once-sacred Hyde Amendment.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Ganjaie, 26, gravitated toward abortion funding after working at Planned Parenthood, where she advocated for legislation to protect abortion rights. Volunteering at the NWAAF, she felt closer to its mission of reproductive justice, a framework developed by black women that supports the human right to all pregnancy options, including abortion and parenting, and recognizes how inequality and racism shape access to health care—even in a state like Washington, with relatively progressive laws. “Passing laws that improve access to abortion is great, but if you’re working three minimum-wage jobs and don’t have access to reliable transportation, then it’s still not accessible to you,” Ganjaie said.

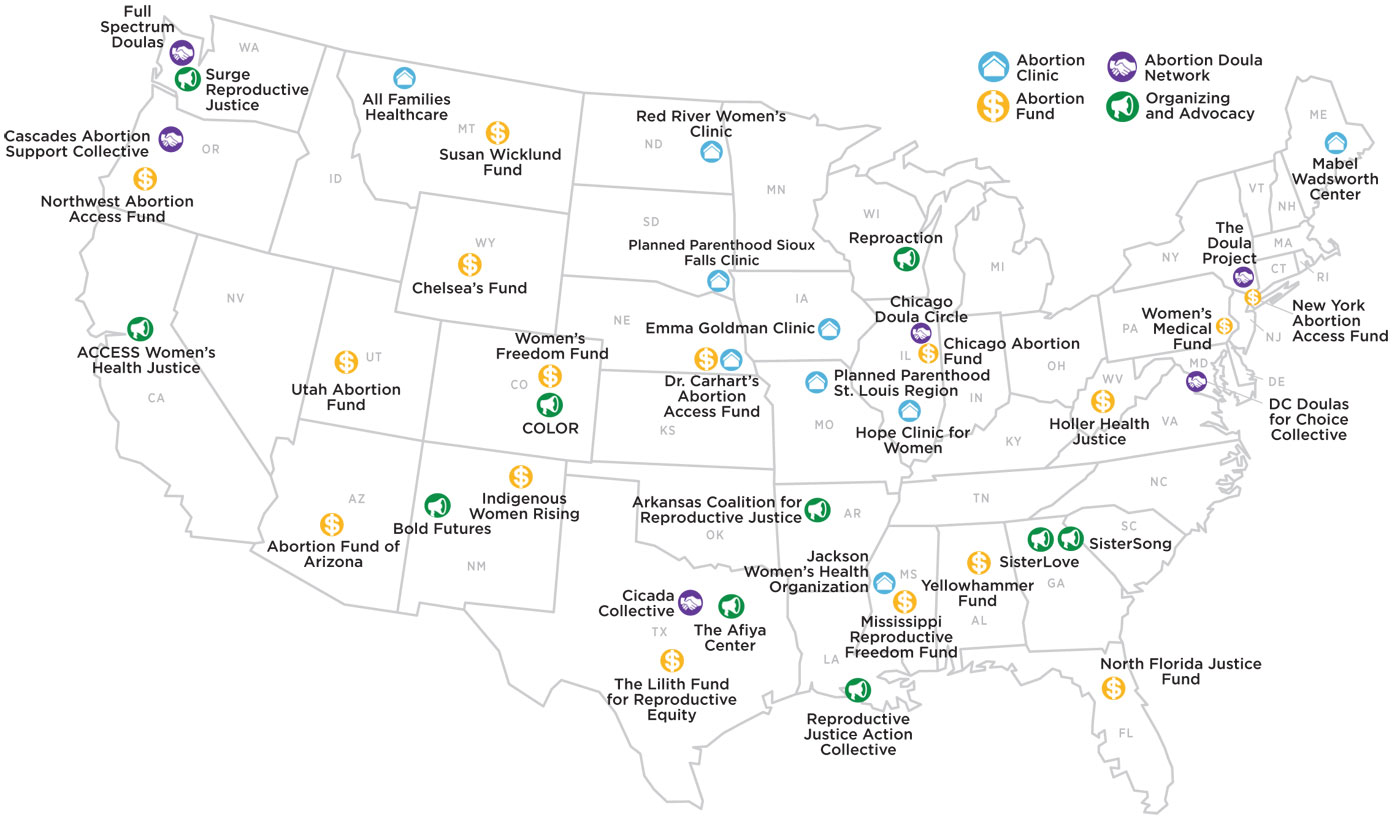

Abortion funds have long operated in that gap. In 2016, the year Donald Trump was elected, the National Network of Abortion Funds (NNAF) launched an effort to build the funds into what it called an “organizing powerhouse.” Now, as states make headlines by passing increasingly extreme laws to restrict or ban abortion, these groups have channeled the growing public awareness of their work into ambitious efforts to expand access. Bolstered by a surge in funding, they have found within the wider abortion rights movement a “greater recognition of the power and possibility of abortion funds to lead,” NNAF’s executive director, Yamani Hernandez, told The Nation. Megan Jeyifo, the executive director of the Chicago Abortion Fund, said there has been a dawning realization among the wider pro-choice public that Roe v. Wade didn’t guarantee access for everyone. “It is time for people to listen to funds, because funds have been doing this work for decades,” she said. “We’ve been ready for this moment. We’re ready to lead.”

Abortion funds have been quietly making abortion accessible despite the nearly 1,300 legal restrictions enacted on the procedure since 1973. Each week, fund volunteers and staff drive people to appointments, host out-of-state patients on their couches, buy bus tickets, provide emotional support, help patients enroll in Medicaid in the minority of states where it covers abortion, and contribute to paying for the procedure. While abortion remains legal, a vast obstacle course of waiting periods, ultrasound requirements, targeted regulations, and bans on second-trimester procedures has rendered it nearly inaccessible in many states. Unable to ban abortion outright, anti-choice lawmakers have relied instead on the power of logistical hurdles to choke off access, patient by patient.

These efforts have taken their toll. Last year the roughly 70 groups that make up NNAF received 150,000 requests and, on average, could help in only one-fifth of the cases, Hernandez said. Those who received help generally had to raise as much as they could on their own and then scrape together the rest from multiple cash-strapped funds. “It usually takes more than one abortion fund to cover one abortion,” she added. The shortfall comes despite a dramatic increase in fundraising; NNAF’s annual bowlathon fundraiser went from raising $940,000 in 2016, before the election, to over $2.4 million in 2019. The network gave away $6.2 million in the 2018 fiscal year—an increase of about $2 million from the year before but a fraction of what it would take to fund every caller. “And that’s in a world with Roe,” Hernandez said.

In May, donations to abortion funds surged after Alabama passed a total ban and other states passed near-total bans, almost all of which have been blocked by courts. In May and June alone, NNAF raised nearly $2 million from individuals—more than twice what it normally receives in a year. In Alabama, the Yellowhammer Fund alone raised $3 million. “It really backfired on [anti-choice lawmakers],” said Amanda Reyes, the fund’s executive director. “They have actually given us the ability to undo some of the damage to abortion access, because now we have the funding to get around their laws.”

Ganjaie and her colleagues started referring to this as the moment “when abortion funds went mainstream.” In addition to a modest uptick in donations, the Northwest Abortion Access Fund saw an increase in callers who were learning about abortion funds from the news. Meanwhile, the funds are preparing for the possibility that the Supreme Court, with Brett Kavanaugh on the bench, might allow further restrictions. Its first opportunity will come this term when it considers a Louisiana law intended to close clinics by requiring providers to have hospital admitting privileges. Advocates warn that the law would shutter two of the state’s three remaining clinics and could prompt a wave of closures across other states. Galvanized by this threat, activists have gone on the offensive with successful campaigns to expand state and municipal funding for abortion. “It’s a perfect time to push bold, progressive legislation,” Ganjaie said, “to be able to really fight for what we want rather than just fight against what we don’t.”

Public funding has long been a priority for the abortion funds, even when it was sidelined at various times by the wider pro-choice movement. Although funds have existed in some form since before Roe v. Wade, the Hyde Amendment spurred activists to form more of these groups, according to Marlene Gerber Fried, a scholar, longtime activist, and cofounder of NNAF. In 1978, Faye Wattleton became the first woman since Margaret Sanger to lead Planned Parenthood and its first black president. At a news conference, she named Medicaid funding of abortion as one of her top priorities, sparking a firestorm among the group’s affiliates. “The concerns were that we were going to lose our federal funding if somebody didn’t get me under control,” Wattleton told The Nation. “My view was: We’re an organization of principles, and we had to stand by and exercise those principles.”

In 1993, with Hyde still in force and Bill Clinton in the White House, momentum was growing for a national health care law. That year, about 20 groups formed NNAF to amplify the call to include public funding for abortion. “It was an intervention in abortion politics,” said Fried. “We were so involved in the tremendous gap between legality and accessibility.” From its beginning, NNAF has been a driving force behind efforts to repeal Hyde. The group joined a successful campaign, led by black activists, to restore the amendment’s exceptions for rape and incest in 1993. The following year, 12 black women, including Toni Bond, gathered in Chicago and coined the term “reproductive justice” to describe a set of concerns that overlapped with abortion funds’ but were focused on the health care needs of black women. “We realized that abortion was not the only issue that was confronting black women,” she told The Nation. “We also knew that…abortion may have been legal, but it was out of reach for most low-income women, owing to the Hyde Amendment.”

The activism against Hyde ramped up again in 2010, after Barack Obama signed a landmark health care law that excluded public funding for abortion. All Above All, led by a coalition that included NNAF, was launched in 2013 to draw attention to how Hyde and related bans have all but blocked abortion access for Native Americans, federal employees, prisoners, detained immigrants, and Medicaid recipients in most states. Two years later, Representative Barbara Lee (D-CA) introduced the Each Woman Act to end Hyde. In 2016 the Democratic Party’s platform called for the amendment’s repeal for the first time. This year, the leading Democratic presidential candidates, including Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, have done likewise, and Joe Biden was forced to reverse his long-standing support for Hyde after intense criticism. The Each Woman Act has collected 171 House cosponsors, although it has yet to be voted on in the House or Senate.

All of this points to a shift in public opinion driven by grassroots activists who have long known they could never fill the gap created by Hyde. “There are some people who mistakenly think that for abortion funds, our goal is to be out here funding every abortion,” said Laurie Bertram Roberts, the executive director of the Mississippi Reproductive Freedom Fund. “That would be great if we could, but guess what? That’s the government’s job.”

After the 2016 election, as the threat of an anti-choice majority on the Supreme Court loomed, members of NNAF gathered in Oakland, California, to prepare. “We literally took out a map and looked at where clinics are, what their gestational limits are, where we saw travel patterns being, where we have funds,” Hernandez said. The groups decided to focus on improving regional networks for patients, who were increasingly compelled to travel across state lines for abortions. From 2012 to 2017, 276,000 women terminated their pregnancies outside their home state, according to an Associated Press analysis. In New York, NYAAF began to track an increase in out-of-state visits. In fiscal year 2017, the group told The Nation, 35 percent of the people who received funds from the group traveled to New York from out of state; the following year, that number rose to 39 percent. That increase and the prospect of an even steeper rise if Roe v. Wade is overturned have prompted NYAAF to ramp up its advocacy, supporting legislation to protect abortion access and launching its historic campaign to get the city to directly fund abortions.

In Texas, abortion funds faced a much darker political landscape. State lawmakers introduced bills to ban most abortions and even to impose the death penalty on those who have them. In more liberal Austin, City Council members approached the Lilith Fund to ask how they could help. “As an abortion fund, anything that really gives people concrete access is going to be our priority,” said Cristina Parker, Lilith’s communications director. So the group asked for funding. The City Council allocated $150,000 to help Austin residents with the travel, housing, and child care costs associated with abortion, hitting back at a new state law that bars the city from funding abortion providers directly. Parker said the resolution was a “direct strike” against the Hyde Amendment, whose creator, the late Republican congressman Henry Hyde, once famously lamented, “I would certainly like to prevent, if I could legally, anybody having an abortion, a rich woman, a middle-class woman, or a poor woman. Unfortunately, the only vehicle available is the…Medicaid bill.”

On September 30, the 43rd anniversary of the amendment’s passage, Parker and dozens of others who supported the Austin City Council’s resolution gathered to celebrate their victory. “We don’t get too many victories…so it feels really good,” she said. Among those in attendance were members of the Austin chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America. With a growing membership spurred by the campaigns of Sanders and Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY), DSA chapters in Austin and elsewhere have channeled their growing political power into supporting abortion funds, which they see as natural allies. “They really do fit in with our idea of a socialist vision,” said Laura Colaneri, a member of the steering committee for the DSA’s socialist feminist working group. “They’re there for each other with emotional support and community support, not just monetary support.” Nationwide, she continued, DSA chapters raised more than $137,000 during NNAF’s annual bowlathon fundraiser this year.

In Chicago, the DSA chapter helped rally support for a state law requiring private insurance to cover abortion, two years after the Chicago Abortion Fund successfully pressed Republican Governor Bruce Rauner to sign a bill approving such coverage under Medicaid. The Medicaid law “changed everything,” said the CAF’s Megan Jeyifo. But coverage for the procedure hasn’t been a cure-all in Illinois or in the 15 other states that use state money to fund abortions through Medicaid, including New York, California, Washington, Oregon, and Alaska. Abortion funds in those states still scramble to help patients who are undocumented immigrants, can’t enroll in Medicaid in time for the procedure, have travel needs or high insurance deductibles, or have private insurance that doesn’t cover abortion. But Medicaid coverage has relieved some of the pressure. “We are able to connect so many more people to care,” Jeyifo wrote in an e-mail, “but there are also many still falling through the cracks.”

As the federal outlook darkens, such state-level efforts to expand access have caught on. Last year there were more measures enacted nationwide to expand reproductive health access than to restrict it, and this past June, Maine became the latest state to require Medicaid and private insurance coverage of abortion.

The year before the 2016 election, a new kind of pregnancy center opened in then-Governor Mike Pence’s Indiana. The group, All-Options, started as an emotional-support hotline for people with unintended pregnancies. In 2015 it opened a storefront in Bloomington as a counterpoint to the anti-choice crisis pregnancy centers, which use misinformation to dissuade patients from seeking abortions. What All-Options envisioned was a truly comprehensive pregnancy center, a one-stop shop for free diapers and day care referrals where patients could get funding and support for abortion. “Our movement is so on the defensive, and today more so than when we opened the center,” said Parker Dockray, the group’s executive director. “We don’t offer as many visions of what we would like to see, what we think is possible, something that’s inspiring and gives people a direction to think about: ‘This is what it could look like.’”

At the national level, Hernandez has sought to move the funds into closer alignment with reproductive justice values by fostering leadership from people of color and those who have received funding from the groups. About a third of the funds have paid staff, which she said is a priority as NNAF broadens its work and prepares for a future of even more restricted access.

Among the groups to embrace the reproductive justice framework is Alabama’s Yellowhammer Fund. This year it plans to open a reproductive-justice resource center in Birmingham, offering formula, diapers, and car seats, as well as sex education and condoms. Recently, Yellowhammer received a call from a doula whose patient was at risk of losing custody of her baby because she didn’t have a crib. The fund bought her one. “That’s reproductive justice, and those are the kinds of things we want to do,” said the fund’s Amanda Reyes. Thanks to the recent surge in donations, Yellowhammer can afford to meet these aspirations. It used to have a weekly abortion funding budget of $650, about what a first-trimester abortion costs. Since June, it has increased that to $9,000, she told The Nation in October. (The group’s approach isn’t always popular within the movement; Yellowhammer and the Mississippi Reproductive Freedom Fund have faced criticism that they should be spending more directly on abortions.)

Perhaps no abortion fund has embodied the sweeping vision of reproductive justice more than the Mississippi Reproductive Freedom Fund, which provides diapers, other baby supplies, and groceries and helps more people than just those seeking abortions. When The Nation reached the MRFF’s Laurie Bertram Roberts in early October, she said the fund’s van—normally used to drive patients to abortion clinics across the South—was also being used to drive people arrested in a series of recent Immigration and Customs Enforcement raids to their court appearances. “I don’t think there’s anything more RJ [reproductive justice] than making sure parents are with their kids, right?” she said. “That’s just as RJ as making sure someone who doesn’t want to parent doesn’t have to be a parent.” She has been encouraged by the victories in New York City and Austin, she said, but in conservative Mississippi, a public funding campaign would have to start with expanding Medicaid coverage in the state, where about 12 percent of the population is uninsured. “We should have full access to free health care—period, full stop,” she said. “Abortion funding is like a stopgap until we get there.

“The goal,” she added, “is for us to not have to do this anymore at all.”