Protest Matters—but We Cannot Forsake the Vote

At the Freedom Rising Conference, faith leaders gather to confront the “existential threat to democracy” posed by Trump.

The Rev. Jacqui Lewis speaks at the Freedom Rising Conference in New York City.

(Angela Dykshorn)Latosha Brown almost canceled her speech at last weekend’s Freedom Rising Conference in New York because, she confessed, she was “in excruciating pain.” And not the physical kind.

Brown is a cofounder of Black Voters Matter, a nonprofit whose work four years ago was foundational to the legislative record that President Joe Biden is touting as one reason to reelect him this November. Black Voters Matter’s 2020 efforts were particularly pivotal in Georgia, where its funding of grassroots outreach helped boost Black voter turnout to record levels. When Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossof won narrow victories there, it gave Democrats control of the US Senate and thus the ability to pass the Inflation Reduction Act, the Infrastructure Investment, and Jobs Act, and other popular pieces of legislation.

But Brown “could not make myself get out of bed this morning,” she said from a podium at the Marble Collegiate Church in downtown Manhattan. Eyes shining with tears, she added, “I’m deeply grieving. My only child, of 29 years, I lost my only child a year ago. Last year, I was in a daze, in a fog…. But now I feel the sting of it.”

It took three or four phone calls from her partner, Brown continued, before she could rouse herself to deliver closing remarks to the second day of Freedom Rising, an annual interracial conference of faith leaders and progressive activists from across the United States. She decided to share her personal story, she told the conference, “because I want us to be honest about what we’re feeling in this moment,” which is “such a dark time in our political history.”

Organized by a team led by the Rev. Jacqui Lewis, the head pastor of New York’s Middle Church, Freedom Rising is now in its 18th year. The Middle Church describes itself as “a multicultural, multiethnic, intergenerational movement of spirit and justice, powered by fierce, revolutionary love, with room for all.” Its two-word slogan is “Just Love,” Lewis told the conference, “and the double-entendre is intentional.”

This year’s Freedom Rising focused on the 2024 elections and what Brown and Lewis both called the “existential threat to democracy” posed by Donald Trump and his supporters.

To build a people’s movement in this “challenging and intense time,” Brown suggested remembering that abolitionist Harriet Tubman guided enslaved people to freedom by relying on the North Star. A funny thing about stars, Brown said, is that while stars are always in the sky, human beings can’t always see them. “You can only see the stars when it’s night,” she said.

“In this dark moment in America’s history,” she continued, her voice rising, “we are the stars. We are the light that is supposed to lead others to the light.”

But are others willing to be led?

The prevailing narrative from the mainstream media is that many Black and other people of color as well as many young people are reluctant to vote for Biden in November. They don’t like how he has handled the war in Gaza, the climate emergency, or any number of other issues. The fact that shunning Biden could bring back Trump, who would almost certainly be worse on those issues (and many others), is said not to move these voters. In close elections, as 2024 is projected to be, even a small decline in voter turnout within these demographic groups could sink Biden.

“I’m honest with young folks: Voting itself is not going to bring Black liberation,” Brown said in an interview after her speech. “We tell young people, ‘This is a moment to use your agency, to create the best possible circumstance in which to organize and build power going forward.’ Young people on my own staff say that I’ve changed their minds by shifting their focus from elections as a choice between two candidates to using voting as a strategic tool to advance their long-term interests. If you connect the power of voting to the issues that young people care about, they do respond. They will vote for their own power.”

Deth Im, the director of faith leadership strategies for the nonprofit Faith in Action, learned a similar lesson after the mass uprising in Ferguson, Missouri, sparked by the police shooting of Black teenager Michael Brown on August 9, 2014. In the three preceding elections in Ferguson, Im told the conference, Black voter turnout had been 8 percent, 9 percent, and 11 percent. The 2015 election was a very different story. After a coalition including Faith in Action, Black Lives Matter, Metropolitan Congregations United, and others registered 3,287 new voters, Black voter turnout soared to 30 percent. Three Black candidates were elected to the Ferguson City Council, the first time a Black person had served on that body.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →“Protest matters, but we cannot forsake the vote,” Im said.

For its part, Black Voters Matter is working in 20 states in 2024 and spending serious money. “We’ve given away over $36 million over the past five years to community-based, Black-led groups,” Brown told me. “This year, we expect to give away $27 million.”

Black Voters Matter’s money goes to locally based organizations that are already active in their communities, working on issues those communities care about and planning to stay active long after Election Day. This approach differs from the transactional model applied by traditional get-out-the-vote efforts, which tend to bring in outsiders who focus on turning out as many voters as possible on Election Day but then disappear until the next vote four years later. That one-and-done approach can leave people feeling used, feeding cynicism about voting as a vehicle for change.

The grassroots organizations Black Voters Matter funds often employ conventional methods of electoral outreach: knocking on doors, getting people registered to vote, driving them to the polls, distributing food and water to folks waiting in line to vote. But they use such activities to form relationships with the people they’re organizing, relationships that can over time help communities develop a shared vision of the social changes those people want to see. As Deepak Bhargava and Stephanie Luce explain in Practical Radicals, building relationships and articulating a shared vision set the stage for using voting, pressure campaigns, and other forms of civic engagement to generate the lasting political power needed to achieve such change.

“Voting isn’t about a popularity contest. It’s about power,” Brown said. “Someone is going to be elected. It’s about voting for whoever is going to be best for reducing harm to your community.” Recalling the special election in 2017 that made Doug Jones the first Democrat to represent deep-red Alabama in the US Senate in 20 years, Brown said, “Our slogan was, ‘It’s not about the Democrats, it’s not about the Republicans, it’s about us.’ We drove record turnout, and that remains our framework for organizing, because it works.”

Brown, Im, Lewis, and the scores of other faith leaders and activists at the Freedom Rising conference were united in the conviction that Trump must be defeated in November. At the same time, they were outspoken that stopping Trump is far from sufficient and that voting is only one tool for achieving the change they want to see, from ending mass incarceration to providing universal healthcare to assuring human rights for all regardless of race, gender, and sexual orientation, to ending US support for unjust wars, and stopping the overheating of the planet.

“We’re standing on the precipice of catastrophe,” Lewis told the conference. Apparently unwilling to utter Trump’s name, Lewis coined a dismissive nickname for the former president: O-Boy, as in Orange Boy. “If the O-Boy is elected, we’re gonna have a fight on our hands,” she said. “And if Biden is reelected, we’re gonna have a fight on our hands. It’s just going to be a different fight.”

More from The Nation

The “Save Chinatown” Coalition Goes on the Defensive in Philadelphia The “Save Chinatown” Coalition Goes on the Defensive in Philadelphia

The construction of a new basketball arena threatens to fill the neighborhood with more traffic and raise rents.

Human Rights for Everyone Human Rights for Everyone

December 10 is Human Rights Day, commemorating the anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), one of the world's most groundbreaking global pledges.

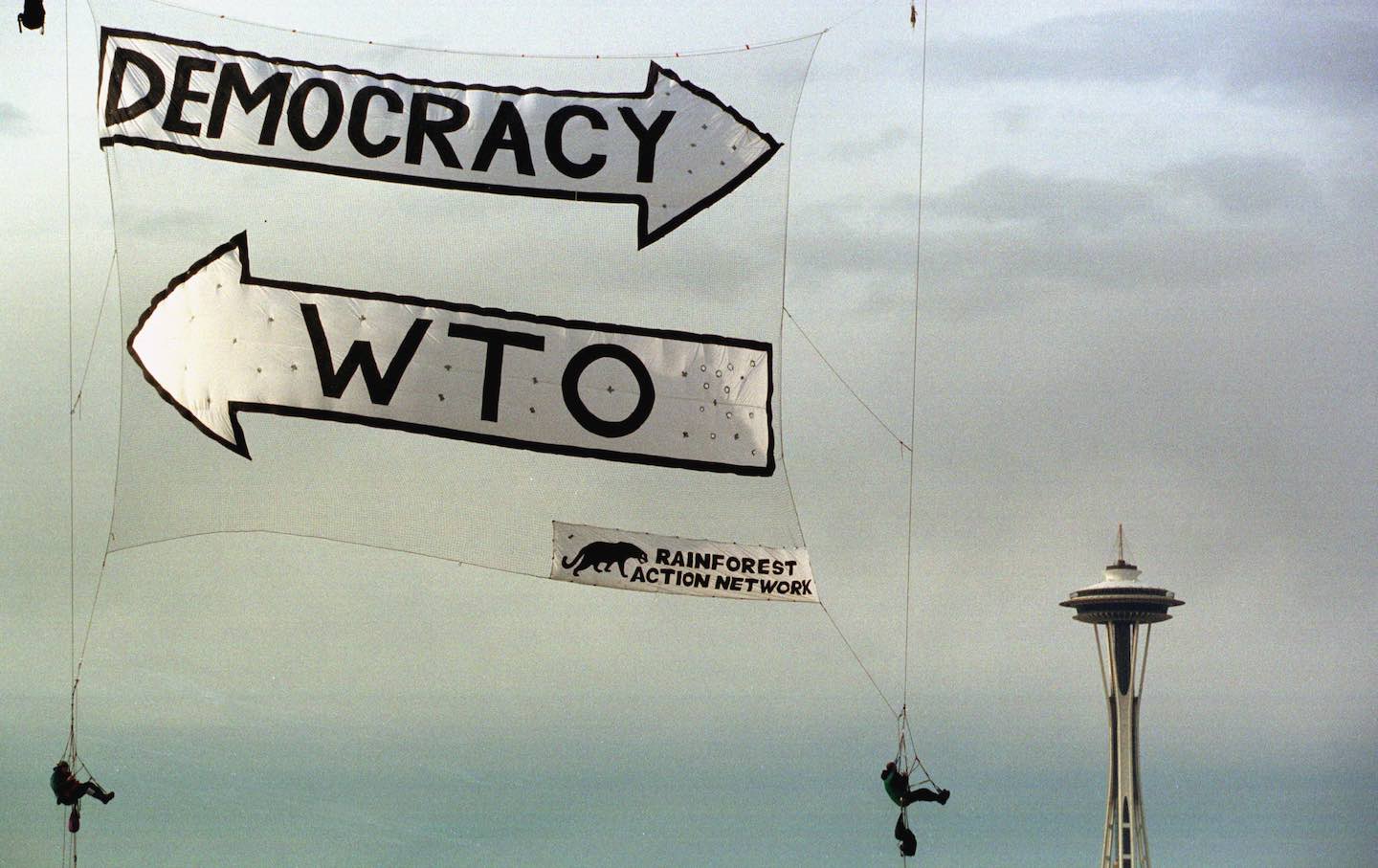

25 Years Ago, the Battle of Seattle Showed Us What Democracy Looks Like 25 Years Ago, the Battle of Seattle Showed Us What Democracy Looks Like

The protests against the WTO Conference in 1999 were short-lived. But their legacy has reverberated through American political life ever since.

Hollywood’s Vocal Actors Union Goes Silent on a Gaza Ceasefire Hollywood’s Vocal Actors Union Goes Silent on a Gaza Ceasefire

Amin El Gamal, head of SAG-AFTRA's committee on Middle Eastern and North African members, has advocated for a statement supporting a ceasefire in Gaza—so far without success

The Mirabal Sisters The Mirabal Sisters

Patria, Minerva, and María Teresa Mirabal were sisters from the Dominican Republic who opposed the dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo; they were assassinated on November 25, 1960, und...

What Will a Peace Movement Look Like Under Trump’s Second Presidency? What Will a Peace Movement Look Like Under Trump’s Second Presidency?

An all-hands-on-deck approach to the coming world of Donald Trump and crew is distinctly in order.