The Chicago Teachers Union Wants to End Student Homelessness at the Bargaining Table

In its next contract, the CTU is demanding housing for up to 15,000 unhoused students.

At the high school where Kevin Moore has taught social studies for seven years, there is no way to separate Chicago’s housing crisis from teachers’ working conditions—or students’ learning conditions. Of the roughly 1,500 students at George Washington High School, on the far southeast side of the city, about 60 students are housing insecure, he said. But that number is expected to rise this year, with an increasing number of migrant newcomers temporarily staying with family or friends, deprived permanent residence, a status referred to as “doubling up.”

“If you’re a child and you don’t know what your living situation is going to be by the end of the week, much less by the end of the day, school is not going to be your top priority,” Moore, 45, said of the high school, which is 88 percent Latino. “We want to give our students the most joyful day possible,” he said, adding that it’s “difficult to do our jobs when a child is struggling, when their attention is elsewhere.”

Now, as chair of the Chicago Teachers Union’s (CTU) housing committee, Moore is trying to change that. The union, officially AFT-IFT Local 1, has made a national name for its willingness to fight—and strike—for demands that consider the broader good of the communities where teachers work and often live. With the contract representing roughly 26,000 educators in Chicago Public Schools (CPS) set to expire on June 30, the union is including bargaining proposals that address the crisis of homelessness among Chicago’s children.

Chief among them is the proposal that the city of Chicago and the board of education agree to become “partners in a pilot program to house homeless families of 5,000 students in Chicago Public Schools with plans to scale that up at the end of the pilot period to house the families of up to 15,000 homeless students,” according to one of the housing proposals, read out loud to Workday Magazine and The Nation. “We will work together with the pilot partners with the goal of eliminating homelessness for families of students in Chicago Public Schools within five years.”

The proposal calls for the board and city to “create 10,000 new affordable housing units. Residents of the city shall have access on a lottery basis, but priority for new public housing units shall be given to CPS students and families.”

Within the CPS system, there are roughly 20,000 students in temporary living situations (STLS), a term that refers to students who themselves or whose parents don’t have a lease or a mortgage. They might be doubling up or living in shelters, cars, hotels, or outside. “What better solution is there than to actually get housing?” said Jhoanna Maldonado, CTU organizer and liaison for the union’s housing committee. “Other than that, you’re just Band-Aiding the problem.”

This would not be the first time a teachers’ union used a contract to try to house students. In its 2021 to 2024 contract, the Boston Teachers Union (Local 66 AFT Massachusetts) won a measure to partner with the city and the school district on a pilot program “to house homeless families of 1,000 students in Boston schools with plans to scale that up at the end of the pilot period to house the families of up to 4,000 homeless students.” That contract states that the union “will work together with the pilot partners with the goal of eliminating homelessness for families of students in Boston schools within five years.”

The exact pathway to housing CPS students would have to be forged through the process, but teachers have no shortage of ideas. Maldonado, who was a teacher before working as an organizer for CTU, said in an interview on March 15 that there are a number of legislative initiatives that could help achieve these goals. “Support public housing, fully fund ‘Section 8’ vouchers, expand other housing programs,” she said. “How do we change policies, laws? That’s something they had refused to do in the past.”

On March 19, Chicago held a referendum over Bring Chicago Home, a measure to increase revenue for affordable housing and homeless services by an estimated $1 billion over 10 years through a progressive amendment to the city’s real estate transfer tax. The effort was supported by a broad coalition of faith groups, community and service organizations, people facing homelessness, labor, CTU, and Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson, who is himself a former CPS teacher and CTU organizer. It was fiercely opposed by real estate and developer interests, which mounted a legal challenge in an attempt to remove the measure from the ballot. While this legal effort eventually failed, “many local media outlets ran with the real estate industry’s misleading messaging, which suggested that the ballot question was removed completely,” Asha Ransby-Sporn reported for In These Times. This was in addition to a host of misinforming ads, Ransby-Sporn added, “intended to scare and confuse voters.” In some cases, landlords contacted tenants and warned them against voting for Bring Chicago Home, according to South Side Weekly reporter Jim Daley.

On the night of March 22, the Associated Press declared that the Bring Chicago Home referendum had been defeated in the polls approximately 53 percent to 47 percent, with 100 percent of precincts reporting, and mail-in ballots unable to significantly shift these numbers.

In response to this electoral outcome, Moore said the CTU’s housing proposals are more important than ever, and the union has no intention of backing down on them. “It doesn’t change our objectives,” he said. “It could energize us.”

Jackson Potter, the CTU vice president, agreed. “We knew any effort to address big and systemic issues like racism and homelessness would require struggle,” he said, in remarks made after the Associated Press called the vote. “And now the real estate industry has picked a fight we intend to win, through our contract, through legislation, through street actions, coalition-building, and growing our movement.”

The union’s housing proposals include other pathways to address the housing crisis. CTU is proposing to establish a working group to identify unused city and Board of Education–owned spaces that could be transformed into affordable housing, Moore summarized. “School buildings that were closed in 2012 and 2013, sitting there vacant, could be rehabbed and modified,” Moore said. “You could identify vacant lots in neighborhoods to identify places where housing could be built.” (Shuttered public schools have already been turned into luxury lofts in Chicago.)

There is precedent for these measures, as well. In the appendix of their 2022 to 2025 contract, the United Teachers Los Angeles won a memorandum of understanding that says the district and the union would establish a joint task force to identify vacant school district ”land parcels that could be used for the development of affordable housing for low-income students and families.” And a 2023 memorandum of understanding says the Oakland school district will work with the Oakland Education Association to identify “possible locations that could be developed into housing for unhoused and housing insecure” students. Both of these agreements were preceded by strikes.

The union is also proposing a partnership with trade unions to create a Career and Technical Education program to construct housing for STLS students. And the CTU wants a pathway for members of the community to become STLS advocates, who help housing-insecure students and their families connect with resources and maintain access to public education, and are allocated to schools based on the number of homeless students who go there. This paid position was won in the last contract for the first time, after teachers also proposed housing for all homeless students, and went on strike in 2019.

Moore said teachers have a special responsibility to curb homelessness. “In the wealthiest nation on the planet, there is definitely enough money to house everyone who needs housing. No one should go without shelter, even for one night, especially children.”

Over the years, Moore said he has known a few students who ran away from home. One, who couch surfed with friends and neighbors, was able to graduate and is in college now. But there are many other students whose housing precarity he may not be aware of. Often it is up to teachers—themselves overworked—to report any concerns to STLS advocates. “I think a lot of the students who are unhoused are doubled up, living with other families, couch surfing, bouncing from family to family member,” he said.

The union’s proposals don’t stop with housing. The CTU is calling for cost of living adjustments, improved bilingual education services, better staffing, improved case manager ratios for special education, and a movement toward greener, more climate-just schools—including removal of all lead pipes.

Bargaining proposals are aspirational documents, and in the case of the CTU, they emerged from an intensive—Moore called it “bottom-up”—process of soliciting feedback. Moore said proposals started being formulated last fall, crafted by committees that are chaired by active teachers, and also include CTU organizers. The union sent surveys to members, and discussed proposals at union meetings. “As part of a summer organizing institute, we fanned out and went to communities throughout the city,” Moore said. “We talked to CTU members and community members. Community members would tell us if they had a chance to reimagine how a school could look in their community, what would they want to see.”

Once the committees compiled their proposals, there were three rounds of proposal meetings, where the executive board, committee chairs, and leadership discussed and debated the language. On March 6, hundreds of members of the union’s House of Delegates gathered for more than six hours to debate the 142 pages of proposals that had made the cut, in a meeting that was open to any CTU member, before the proposals were finally put to a vote.

One of the next steps is negotiations. Maldonado said that, historically, the district has been reluctant to engage in serious negotiations until the union has shown willingness to strike. Teachers are hopeful it will be different this time under the Johnson administration.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →When discussing the union’s housing proposals, Moore referenced bargaining for the common good, the idea that contracts can be used to win broader social goods and that labor and community groups can—and should—work together. This concept is related to social-justice unionism, which has been present at various points in US labor history: the United Packinghouse Workers of America, which fought racist hiring practices in the 1950s and opposed racial segregation; ILWU Local 10, which refused to unload cargo delivered from apartheid South Africa; and CTU itself, which struck in 2012 in part to oppose corporate education reform.

An estimated 82 percent of the more than 68,000 people facing homelessness in Chicago are people of color, with Black communities disproportionately bearing the brunt and Latino Chicagoans also heavily affected, according to the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless. “The issue is equity,” Moore said. “The lack of affordable housing is the number-one cause of homelessness in Chicago. We’ve seen years of redlining.”

Of course, the CTU has its opponents, among them the anti-union, billionaire- and corporate-funded Illinois Policy Institute, which has sought to frame the union’s ambitious bargaining demands as examples of teacher overreach. (The think tank obtained and published some summaries of bargaining proposals.) But Moore said that communities admire the CTU for its very willingness to fight hard for its members and the neighborhoods in which they labor. “They are going to do anything to try to make us look bad and break up our union,” he said. “We have power; we’re well organized; we have support. We are fundamentally trying to reimagine and change how public education looks in Chicago. There will always be pushback against that.”

“People come at us and say, ‘Do you think housing is something we should be fighting for?’ Absolutely. We have almost 20,000 homeless students. That is unacceptable.”

More from The Nation

Yale Students Voted to Divest, but What’s Next is Unclear Yale Students Voted to Divest, but What’s Next is Unclear

The referendum calls on the school to divest its $41 billion endowment from military weapons manufacturing firms, yet the power to do so is in the hands of the board of trustees.

The “Save Chinatown” Coalition Goes on the Defensive in Philadelphia The “Save Chinatown” Coalition Goes on the Defensive in Philadelphia

The construction of a new basketball arena threatens to fill the neighborhood with more traffic and raise rents.

Human Rights for Everyone Human Rights for Everyone

December 10 is Human Rights Day, commemorating the anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), one of the world's most groundbreaking global pledges.

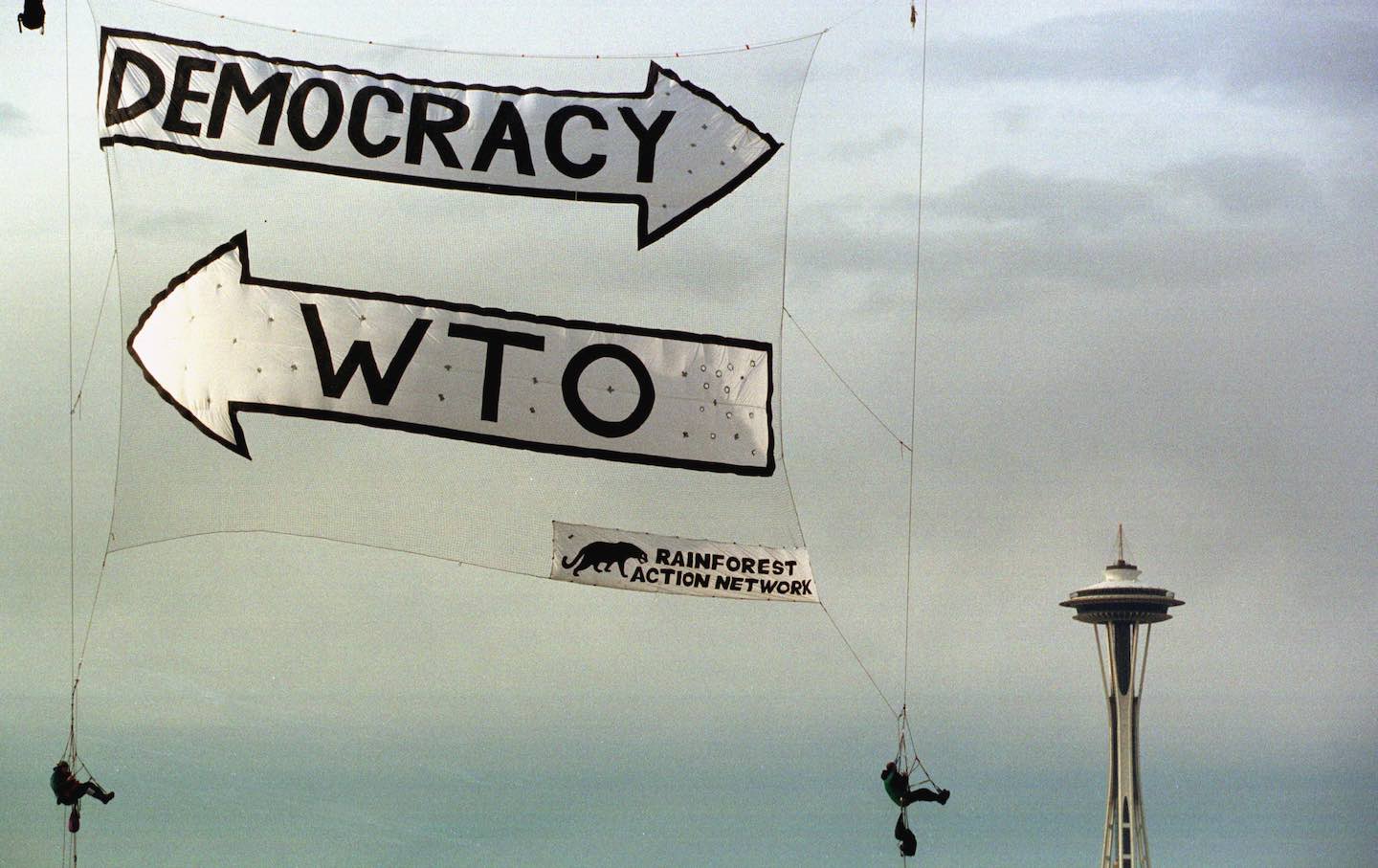

25 Years Ago, the Battle of Seattle Showed Us What Democracy Looks Like 25 Years Ago, the Battle of Seattle Showed Us What Democracy Looks Like

The protests against the WTO Conference in 1999 were short-lived. But their legacy has reverberated through American political life ever since.

Hollywood’s Vocal Actors Union Goes Silent on a Gaza Ceasefire Hollywood’s Vocal Actors Union Goes Silent on a Gaza Ceasefire

Amin El Gamal, head of SAG-AFTRA's committee on Middle Eastern and North African members, has advocated for a statement supporting a ceasefire in Gaza—so far without success

The Mirabal Sisters The Mirabal Sisters

Patria, Minerva, and María Teresa Mirabal were sisters from the Dominican Republic who opposed the dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo; they were assassinated on November 25, 1960, und...