The Long Shadow of the “Jewish Question”

After the Holocaust, Israel was hailed as the solution to an essentially antisemitic debate. Now, as another genocide unfolds—in Gaza—Jews are once again questioning the question.

In late August 1908, some 70 delegates crowded into a hall in Czernowitz, the cosmopolitan capital of Austrian Bukovina. They had come from Warsaw and Galicia and cities across Eastern Europe for the First Yiddish Language Conference. Leading writers like I.L. Peretz were present; Sholem Aleichem had wanted to attend but was kept away by illness. For five days, they argued about the nature of Jewish languages and whether the one named in the conference title—the one spoken by Eastern Europe’s Jewish masses—was a legitimate national tongue or merely a corrupted jargon of exile.

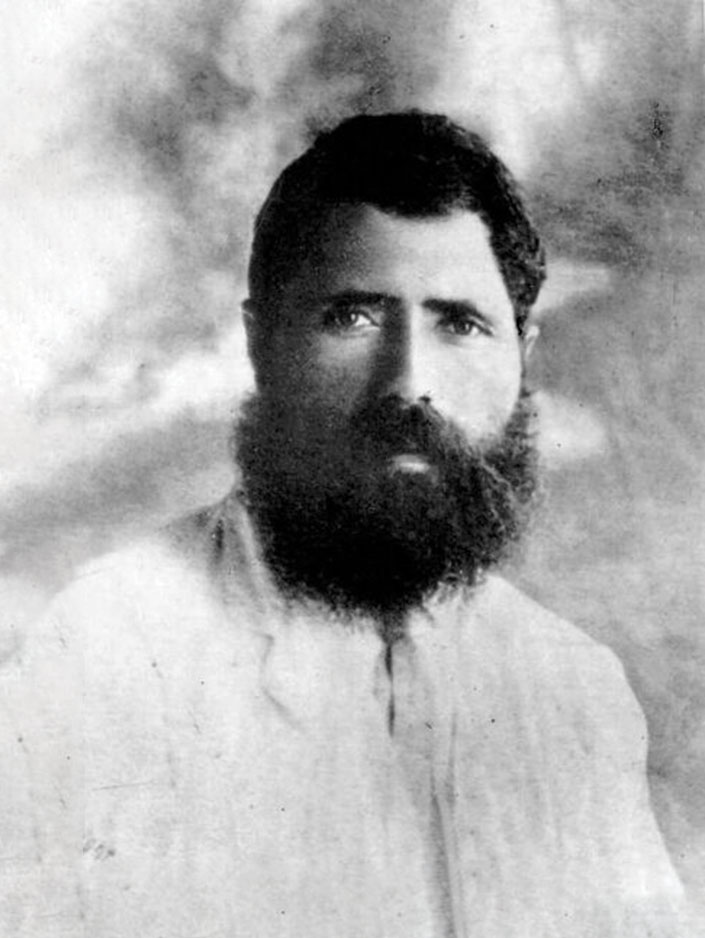

For Nathan Birnbaum, the man who had organized the gathering, this was not a matter of mere academic import; it was a question of existential significance. Born in Vienna in 1864 to an assimilated family, Birnbaum had grown up largely secular yet rejected the assumption that Jews should dissolve into the surrounding German-Austrian culture. With his determined stare and full beard projecting well below his throat, he could be easily mistaken for Theodor Herzl at the time.

The two men had, in fact, been allies for a period. Nearly two decades earlier, in 1890, Birnbaum had coined the term Zionism while editing the early Zionist journal Selbst-Emanzipation (Self-Emancipation), and he was later elected secretary-general of the Zionist Organization at the First Zionist Congress in Basel. Later, however, he would abandon the Zionist movement and, in its stead, embrace a different vision for the future of the Jewish people—one that diverged wildly from political Zionism and was the implicit focus of the Czernowitz ingathering.

Birnbaum did not believe that the Yiddish-speaking Jews scattered from the Baltics to the Black Sea were failed Europeans awaiting transformation in Palestine, as the Zionist movement argued. Rather, they were a living nation deserving recognition where they already stood. The Czernowitz conference was meant to formalize this recognition by declaring Yiddish the national language of the Jewish people, not merely one among several. Such a declaration would have been a direct challenge to the Zionist project, which was busy reviving Hebrew as the tongue of a future state and dismissing Yiddish as a debased lingo of the diaspora.

But it was not to be. The conference included some Hebraists and Zionist sympathizers who refused to abandon Hebrew. The resulting compromise declared Yiddish “a” national language rather than “the” national language, preserving a role for Hebrew and the political vision it carried. Yet even in that careful phrasing, we can see the outlines of a long-buried history: an entire countertradition to the Zionist project that Birnbaum had once helped build.

More than a century after the Cernowitz conference—after Birnbaum had turned away from Zionism and toward diaspora—the questions that propelled his transformation have returned with a fierce urgency among a small but growing cohort of Jews. Horrified by the ongoing annihilation of Gaza and the slow-motion ethnic cleansing of the West Bank, they have begun to challenge the orthodoxy that undergirds Zionism—and, with it, to entertain ideas that were unthinkable only a few years ago.

Palestinians, of course, have understood these ideas for decades. What feels like a discovery to some diaspora Jews is what Palestinians have been saying since Zionism’s logic was first enacted upon them. And yet, as Birnbaum’s story suggests, the critiques now taking shape in the corridors of Jewish life are not altogether alien to the tradition. Today’s generations simply aren’t aware of it.

This is not an accident. The words of men like Nathan Birnbaum appear in virtually no Hebrew-school curricula, and their ideas are featured in no synagogue sermons. Their absence from the story, however, is part of the story. Thinkers like Birnbaum were pushed aside because they complicated a narrative that needed to feel inevitable: that Zionism is the only viable answer to Jewish existence in the modern world.

When Birnbaum lived, this was a hotly debated notion—argued over, countered, and even opposed from Warsaw to New York. In those days, multiple visions of the Jewish future existed, competing for allegiance, and Zionism’s current form was neither inevitable nor uncontested. The alternatives were themselves sophisticated political movements, with millions of adherents who understood Jewish existence differently from the territorial nationalism that eventually prevailed. Even now, their insights remain available, if obscured, ready to be recovered by those willing to look.

To understand how all these movements came to emerge at roughly the same time and place, it’s necessary to revisit a debate then roiling Europe about the role of Jews in European societies. This debate was known as the “Jewish Question,” and it did not originate with Jews. European Christians took it up in the decades following the French Revolution, when newly emancipated Jews began claiming citizenship in countries that had confined them to ghettos for centuries. Philosophers and politicians who called themselves liberals asked whether Jews could be loyal citizens of nations while remaining a “separate” people. The question was inherently antisemitic, treating Jewish difference as an anomaly that threatened the coherent nation-states Europeans were trying to build.

By the late 19th century, Jews had internalized this framing and began to offer their own answers. Some chose baptism or cultural assimilation. Others, like Birnbaum and then Herzl, proposed nationalism. Still others insisted on socialism or religious renewal. Yet in a number of these instances, the question itself went unquestioned. Rather than rejecting the framing of the Jewish Question, political Zionism, for example, internalized it and offered territorial sovereignty as the answer. Accepting the validity of the question meant accepting that something about Jewish existence needed to be fixed. Being Jewish in the diaspora was a pathology requiring a cure in the form of a political arrangement.

Birnbaum’s answer was to invert the premise. Encountering the Yiddish-speaking masses of Eastern Europe, he later recalled, “I found them to be a people with all the signs of a living, separate nation; it became more and more clear to me that a nation that already exists does not have to be created again.” His solution for this challenge was Golus-Natsyonalizm, or diaspora nationalism. The term was a provocation. Golus, the Yiddish word for exile, had always carried negative connotations in Jewish thought, rooted in the biblical concept of galut as divine punishment for Jewish sin and exile from the promised land after the Temple’s destruction. Zionists used it to describe the shameful condition of Jewish dispersion that their movement would finally cure.

In explaining his break with the movement he had named, Birnbaum argued that “it is arbitrary to regard all cultural beginnings in the Golus simply as valuable cultural manure for just one potential culture on a soil which is not yet ours.” Jews had maintained a distinct identity across centuries without sovereignty. Rather than viewing this as a deficiency to be corrected, he proposed understanding it as a unique form of national existence. Nations did not require territory to exist. The millions of Yiddish speakers scattered across Eastern Europe already constituted a nation through their language, their institutions, and their shared culture. They did not need to go anywhere.

Birnbaum left behind no institution bearing his name, but he did leave a legacy of searching that never arrived at a destination. Within a decade after the Yiddish Language Conference, he had undergone what later Orthodox writers would describe as a baal teshuvah journey—a return to religion. He began arguing that Jewish peoplehood was primarily covenantal rather than political. Jews were God’s people before they were a nation in any modern sense. National revival without Torah was spiritually empty. Worse, it risked becoming idolatry of power.

Birnbaum turned from Zionism because he recognized that national self-assertion accepted the antisemitic premise it claimed to escape. Diaspora nationalism offered something better—cultural autonomy without displacement—but he lived long enough to suspect that it could not protect communities from destruction. What Birnbaum grasped by the end of his life was that the question itself was the trap: Asking where Jews could be accepted assumed that they were not already. The real issue was whether states could tolerate plurality, and on that question the 20th century would deliver a terrible verdict.

The Holocaust was Hitler’s answer to the Jewish Question. The Nazis called it the Endlösung der Judenfrage—literally, the final solution to the Jewish Question—and murdered 6 million Jews in pursuit of it. Communities that had endured for centuries were erased, from Warsaw to Thessaloniki. But even amid so much horror, the genocide did not convince the world to abandon the question that had proved so destructive to Jewish existence. Instead, it drove its survivors toward a different answer: territorial sovereignty.

“A Jewish people cannot be kept alive without a Jewish country,” declared David Ben-Gurion, who would become Israel’s first prime minister, at the World Zionist Conference in 1945. It was a message that he, and then many others, would continue to press.

Yet the lessons of the catastrophe were more ambiguous than the Zionist narrative allowed. The Holocaust revealed not the failure of diaspora strategies but the lethal consequences of European nationalism, the very ideology that Zionism sought to join rather than transcend. And Europe’s enthusiastic support for a Jewish state reflected something other than philosemitism. The postwar displaced-persons camps were full of Jews who could not return to their former homes because their communities had been erased, and all too many of their former neighbors did not want them rebuilt. A Jewish state in Palestine solved Europe’s Jewish problem while absolving European guilt. It redirected the surviving remnant toward the Middle East rather than demanding their reintegration into societies that had betrayed them. Zionism’s triumph owed as much to European rejection as to Jewish embrace.

At the same time, Zionism had little initial appeal for millions of Jews who lived beyond the borders of Mitteleuropa. The Jewish Question had also always been a European question, born from the specific pathology of Christian antisemitism. For Jews in the Middle East and North Africa, the question was framed differently, if it was framed at all. They faced discrimination and occasional violence, but not the same existential debate about whether Jewish existence required justification or a cure. The Israeli sociologist Yehouda Shenhav has argued that Zionism simultaneously needed and structurally marginalized these Jews. Israel required their bodies for demographic weight against Palestinians while also subjecting them to what Shenhav calls “de-Arabization,” or the forced shedding of the Arabic language and culture. Communities like the Iraqi Jews, which had been distant from political Zionism even when they harbored the traditional yearning for Zion, found themselves conscripted into a project that denied both their Arab belonging and their agency—making them, in Shenhav’s formulation, “other victims” of Zionism, alongside Palestinians.

Even among American Jews, the Zionist project met with ambivalence. Before 1967, Israel remained a small and struggling state that inspired philanthropy but little identification that could compete with their American identity. The conflict that would become known among Israelis as the Six-Day War, and among Arabs as the 1967 war, changed everything. Israel’s dramatic victory over the Arab armies created a new emotional center for American Jewish life by fusing ancient religious longing with modern military triumph and the promise of a thrilling alternative identity in ways that proved irresistible. Within a decade, support for Israel had become the organizing principle of American Jewish institutional life. The competing answers to the questions of Jewish existence that had flourished before the war receded as Israel moved to the foreground. By the 1980s, most American Jews could not remember that any alternative had ever existed.

That consensus has begun to fracture. The cracks appeared well before October 7, 2023, in the growing discomfort of younger Jews who could not reconcile what they had been taught about Jewish values with what they saw Israel doing in their name. Israel’s ongoing genocide in Gaza accelerated what was already underway. For a growing number of Jews, the question is no longer whether Israel has gone too far in this particular military campaign. The question is whether Zionism has led somewhere they can no longer follow.

This rebellion matters even if it’s statistically small because it undermines the generational project of Jewish communal support for Israel—a project that has played no small part in shoring up the state through funds, fresh immigrants, and foot soldiers. It also threatens the political architecture that American Jewish organizations spent decades constructing.

Politicians have long equated support for Israel with securing Jewish votes and donations, an assumption that has shaped everything from military aid to UN vetoes. The conflation of Jewish interests with Israeli interests was never quite accurate, but it has functioned as political reality because the major Jewish organizations enforced it and punished any deviation. This revolt offers the potential to reshape the political calculations that have underwritten American support for Israel in both parties, which is precisely why defenders of the old consensus treat every crack as an existential threat requiring immediate containment. And why retrieving the history of early dissenters matters.

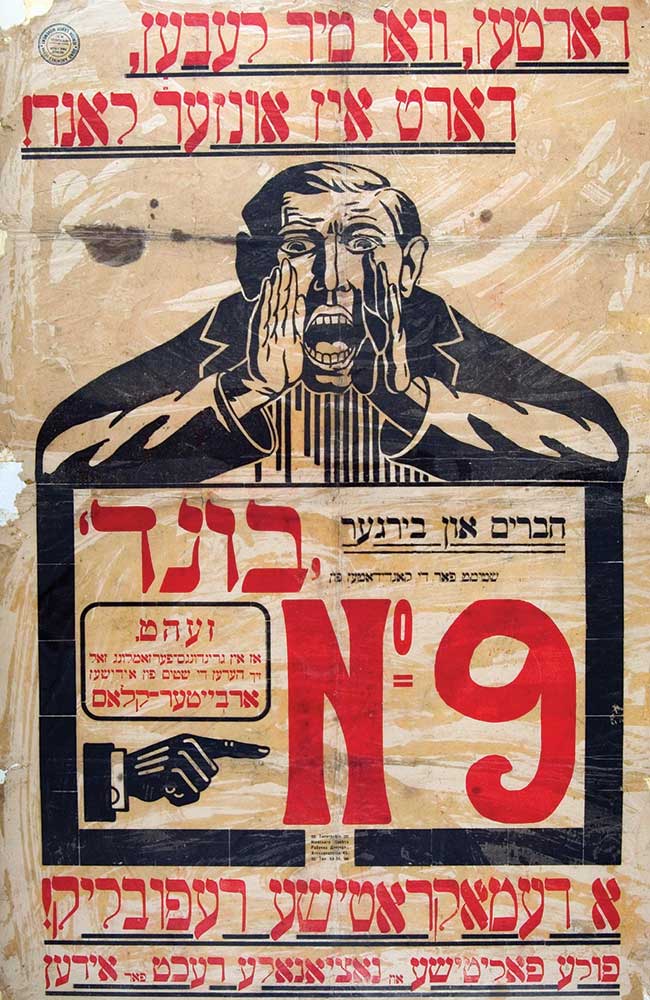

Nathan Birnbaum was not alone in recognizing where the Zionist project was heading. In the movement’s early decades, the General Jewish Labor Bund, which at one point numbered 100,000 members spread across the Pale of Settlement, rejected territorial nationalism for socialist internationalism. Orthodox rabbis denounced Zionism as a heretical attempt to force the divine hand. Reform Judaism in the United States declared that Jews were a religious community, not a nation, and wanted no part of a Jewish state. Even committed Zionists argued furiously among themselves about whether the goal was political sovereignty or cultural revival, and how those goals might be accomplished.

The Hebrew writer Yosef Haim Brenner was wrestling with these questions from within Ottoman Palestine, where he had immigrated in 1909 to work the land and participate in the Zionist project he would later come to critique. Born in present-day Ukraine in 1881, Brenner had come to Zionism through literature as much as through politics. He was drawn to the dream of reviving Hebrew as a living language capable of expressing modern Jewish consciousness. Slight and intense, with the appearance of someone who slept too little and worried too much, Brenner had already established himself as a major literary voice before arriving in Jaffa. His stories and essays transformed Hebrew from a language of prayer and sacred texts into one that could capture the ambivalence and despair of contemporary life. He had done as much as anyone to make the Zionist cultural revival possible, which made his growing critique feel like betrayal to pioneers who believed they were building something unprecedented in Palestine’s fields.

Where Birnbaum in Czernowitz saw Yiddish-speaking communities as a living nation that needed recognition rather than relocation, Brenner in Jaffa watched Zionist settlement and saw ancient patterns of exclusion in modern political form. Brenner shared the anxiety of contemporaries who saw the Zionist project as built on a volcano. In letters, he was direct about the situation in Palestine: “You want to provide refuge for an injured sparrow in a rooster’s coop?” The two men occupied opposite poles of the Jewish world—Birnbaum championed diaspora as home, while Brenner made the journey to the ancestral land—yet both arrived at the same basic recognition: A movement that accepted Jewish existence as a problem requiring solution would create a state that embodied that problem rather than transcend it.

Brenner saw the self-deception at the heart of the enterprise but didn’t live long enough to watch it play out. He was murdered in the 1921 Jaffa riots, and his death became a symbol of Zionist sacrifice, while his warnings about the violence that territorial nationalism would generate on all sides were largely forgotten.

At the same time that figures like Birnbaum and Brenner began to question where the Zionist project was heading, the Bundist movement offered yet another sophisticated alternative that history destroyed rather than defeated. Founded in Vilna in 1897, the same year as the First Zionist Congress, the General Jewish Labor Bund built what aimed to be an entire civilization within the Russian Empire and later Poland, based on the principle that Jewish workers’ liberation would come through solidarity with their neighbors rather than separation from them. Where Birnbaum emphasized cultural autonomy and Brenner wrestled with the self-deceptions of the pioneers in Palestine, the Bund insisted on class as the fulcrum of Jewish fate and identity. Jewish factory workers in Warsaw had more in common with Polish workers in the same factories than with Jewish bankers in Berlin, and class solidarity could transcend ethnic division if given structural opportunity rather than being undermined by nationalist separation.

The Bund rejected the very premise of the Jewish Question, insisting that Jews didn’t need to go anywhere or become anything other than what they were. What they needed was cultural autonomy, political representation, and economic justice where they already lived. The movement’s institutional ambitions matched its ideological ones. Yiddish schools taught Jewish children their history and culture without Zionist ideology, while theaters produced plays that spoke to contemporary Jewish life rather than biblical fantasy.

The Bundists worked vigorously throughout the early 20th century to offer a distinct vision of a Jewish future until most of them were murdered by Nazis and Soviets alike, their institutions destroyed and their leaders executed. Vanishingly few lived to see what came next. In the decades that followed, the erasure of these alternatives came to serve a political purpose: Their destruction was recast as proof of their failure, while Israel’s survival became proof of Zionism’s success. The logic was circular but effective: Zionism’s competitors had been eliminated, which meant Zionism must have been right all along. To suggest otherwise was not only to engage in folly but to flirt with antisemitism.

These days, some Jews have begun suggesting otherwise and doing so in the name of Jewish tradition itself.

The most unexpected institutional expression of this recovery may be the revival of the American Council for Judaism. Most American Jews have never heard of it, in part because the organization’s opponents worked to ensure it would be forgotten. “They tried to cover the footprints of the folks that they exiled from the tent,” Rabbi Andy Kahn, who now leads the reconstituted ACJ, told me. The organization was founded in 1942 by 36 Reform rabbis who believed that their movement, in embracing Zionism, was abandoning its founding principles. (The Union for Reform Judaism officially endorsed Zionism in 1937.) They specifically pointed to the 1885 Pittsburgh Platform, which included the declaration that Jews “consider ourselves no longer a nation, but a religious community.” For more than half a century, this was mainstream Reform theology. The ACJ grew to 14,000 members by 1948 before collapsing after the 1967 war.

Then came the genocide in Gaza. In September 2024, the ACJ revamped its board and appointed Kahn as executive director. “The ACJ is being reconstituted as it is now because it was the last gasp of a mode of Reform Judaism that was completely crushed under the heel of Zionism in America,” Kahn explains. Kahn had served as associate rabbi at Temple Emanu-El in New York from 2018 to 2023, the same congregation where a group of Reform rabbis had founded the ACJ eight decades earlier. His path from one of American Judaism’s most prestigious pulpits to leading its most marginal institution traces the transformation underway. “This generation has now realized—and been told pretty explicitly by the people in highest power in the Reform movement—that there’s no space for us in the movement,” Kahn says. “If we want something, we’re going to have to make our own way.”

In April 2025, Kahn publicly declined an invitation to speak at Emanu-El’s anniversary service because Israeli President Isaac Herzog was listed as a speaker. For Kahn, the goal is not simply opposition, but the construction of something beyond the current impasse. “There’s no way out of the Zionist hegemonic claim to American Judaism that isn’t through it,” he says. “So you can’t just pretend like it’s not there.” He adds, “You do have to process it and move beyond it. But that has to be the goal. The goal can’t be staying here and just fighting Zionists forever. The goal has to be a much wider horizon of a Judaism that is beyond that.”

The shift extends beyond the United States. In the United Kingdom, Na’amod has built a movement that has grown from roughly 200 members to more than 700 since October 2023. “A lot of the people who have joined in the last few years, myself included, are kind of newer to this side of activism, to this particular issue, but felt moved to join,” says a Na’amod organizer who declined to be named for fear of retribution. They gather for Shabbat dinners and organize protests against Israel’s occupation of Palestinian land outside the Foreign Office. Founded in 2018 after Israeli soldiers shot unarmed Palestinian protesters at the Gaza fence, the group recited Kaddish in Parliament Square for the Palestinian dead and has since gained what one sociologist called “influence disproportionate to their size.”

The theological grounding for this work echoes Birnbaum’s diaspora nationalism. The Na’amod representative described a workshop on the Shema, the twice-daily prayer that constitutes Judaism’s central declaration of faith, that reframed her understanding of Jewish life. “It was that Judaism is something we carry around us and that we create around us. It’s not something that is in the land,” she says. “It’s not something that we need from a place.” Birnbaum would have agreed that Jewish existence never required territorial sovereignty because the tradition itself is portable, sustained by practice, text, and community rather than borders.

Meanwhile, in 2024, the Jewish Council of Australia formed to explicitly challenge the claim that established Zionist organizations spoke for all Jews. When the council called for sanctions on Israel and an end to military ties, it framed its position as emerging from rather than contradicting its members’ Jewishness. “Opposing this genocide is an expression of our Jewishness and an honouring of our ancestors who were themselves the victims of genocide,” they wrote, articulating what increasing numbers of diaspora Jews have come to believe.

The December 2025 attack on a Hanukkah celebration at Bondi Beach, which killed 15 people in the deadliest antisemitic violence in Australian history, tested this position under the most extreme circumstances. The Jewish Council condemned the massacre unequivocally while rejecting “weaponising the Bondi massacre to push bigotry, hatred and division.” Max Kaiser, a cofounder of the council, called the remarks by Australia’s antisemitism envoy linking pro-Palestinian protests to the shooting “highly irresponsible.” The council’s position—that genuine antisemitism must be fought without abandoning solidarity with Palestinians—represents the critical ground these new Jewish formations are trying to hold: rejecting both the violence done to Jews and the instrumentalization of that violence to silence criticism of Israel.

While these movements are similar, what unites them is not a single political program but a shared refusal to let the Israeli state define what Jewish identity means. They are recovering, whether consciously or not, something Birnbaum understood when he moved from Zionism to diaspora nationalism to religious anti-Zionism. Each of his phases represented a different answer to what Jews owed the world and what the world owed Jews, and each took seriously the possibility that territorial sovereignty might not be the answer at all.

These groups also recognize the binding role of tradition in building organized institutions that embody different answers to the question of what Jewish life should look like. The congregation Tzedek Chicago celebrates Sukkot by gathering oak and sumac leaves from local trees rather than the four species traditionally grown in Israel. The substitution is deliberate. Rabbi Brant Rosen calls this approach “Diasporism,” a conscious immersion in local culture that treats the land where Jews actually live as home rather than as exile.

Jewish Voice for Peace, another group in the United States that has gained significant sway and members in recent years, speaks of constructing a “Judaism beyond Zionism,” meaning synagogues, study groups, and ritual communities whose identity does not depend on an attachment to any state. The practical implications extend beyond liturgy. These groups argue that thriving diaspora life is not a deficiency awaiting a territorial cure but a legitimate form of Jewish existence that predates and will outlast the current crisis—and is, in fact, necessary to resolving it.

Israel’s existence was meant to have resolved the centuries-old debate about whether Jews could thrive as a distinct people in a world of nation-states. But as the last decades have made painfully evident, territorial sovereignty has offered no escape from nationalism’s violence; it simply shifted its terrain.

On November 29, 1947, the United Nations General Assembly adopted Resolution 181(II), titled “Future Government of Palestine.” The document emerged from the Ad Hoc Committee on the Palestinian Question, which proposed to partition the land into separate Jewish and Arab states. At the precise moment when Europe’s great powers declared the Jewish Question answered, they formally created another. The resolution offered an answer to a problem Palestinians had not created and didn’t seek. Palestinians have always known the two questions were inseparable. Most Jews refused to see it.

Palestinians did not require a UN resolution to understand what they were experiencing. Zionism’s answer to the Jewish Question was their catastrophe. When Israel declared independence in 1948, the event Palestinians call the Nakba displaced roughly 750,000 people from their homes. What one people celebrated as statehood, another experienced as destruction.

Some Jews understood this connection from Zionism’s earliest stirrings. Birnbaum recognized that a movement built on the idea that Jewish existence required justification would produce a state that demanded justification from others. But in recent decades, most diaspora Jews have refused to hold both histories in view. It has proven easier to treat Israel as one story and Palestine as another.

The genocide in Gaza has made that separation impossible. In claiming to resolve Jewish vulnerability, Zionism produced Palestinian dispossession, and now the two questions are permanently bound together, helixed by the violent history that joined them. This is what the movements emerging across the diaspora have begun to understand, even when they cannot always articulate it. The fates of the two peoples are now intertwined, which means any honest reckoning with one question requires reckoning with the other.

The Palestinians killed in Gaza are not collateral damage in Israel’s self-defense but the latest victims of a question that should never have been asked. Every bomb that falls on Rafah demonstrates that the cure is also the disease. A movement that accepted the premise of Jewish abnormality and sought statehood as a remedy has produced a state that enacts abnormality upon others.

What Birnbaum finally grasped was that the question itself was the trap. To ask how Jews could be acceptable was to accept that they required justification. The same logic now confronts Palestinians who are asked to prove their worthiness for rights that should need no proof. The Jews walking away from Zionism are rejecting both frames. They are proposing an identity that doesn’t need to be defended through domination. The answer to what it means to be Jewish need not come at Palestinian expense.

Your support makes stories like this possible

From Minneapolis to Venezuela, from Gaza to Washington, DC, this is a time of staggering chaos, cruelty, and violence.

Unlike other publications that parrot the views of authoritarians, billionaires, and corporations, The Nation publishes stories that hold the powerful to account and center the communities too often denied a voice in the national media—stories like the one you’ve just read.

Each day, our journalism cuts through lies and distortions, contextualizes the developments reshaping politics around the globe, and advances progressive ideas that oxygenate our movements and instigate change in the halls of power.

This independent journalism is only possible with the support of our readers. If you want to see more urgent coverage like this, please donate to The Nation today.

More from The Nation

Gaza Is Still Here Gaza Is Still Here

Despite a “ceasefire,” Israel’s killing has not ended. Neither has the determination of the Palestinian people to survive.

The Ghosts of Colonialism Haunt Our Batteries The Ghosts of Colonialism Haunt Our Batteries

With its cobalt and lithium mines, Congo is powering a new energy revolution. It contains both the worst horrors of modern metal extraction—and the seeds of a more moral economics...

The Repeating History of US Intervention in Venezuela The Repeating History of US Intervention in Venezuela

A look back at The Nation’s 130 years of articles about Venezuela reveals that the more things change, the more they stay the same.

Inside Ukraine’s Underground Maternity Wards Inside Ukraine’s Underground Maternity Wards

Four years after Russia launched its full-scale invasion, Ukrainian health workers are shoring up maternity care to protect the most vulnerable—and preserve Ukrainian id...

How Heidi Reichinnek Saved Germany’s Left How Heidi Reichinnek Saved Germany’s Left

The co-leader of Die Linke helped rescue the party and make it into a political force. But can she beat back Germany’s ascendant far right?

“We Are All Passengers on the Titanic” “We Are All Passengers on the Titanic”

An interview with Grigory Yavlinsky.