The Power Sweepstakes

Uganda and the contradictions of decolonization

Mahmood Mamdani’s Uganda

In his new book Slow Poison, the accomplished anthropologist revisits the Idi Amin and Yoweri Museveni years.

Idi Amin in Kampala, 1975.

(Jean-Claude Francolon / Getty)

As a wandering freelance reporter in West Africa at the end of the 1970s, I followed the lurid spectacle of Jean-Bédel Bokassa, a former sergeant major in France’s African colonial army. A veteran with the Free French Forces during the liberation of France from German occupation in 1945, Bokassa returned home to his native Central Africa shortly afterward and rose with irresistible swiftness after it achieved independence in 1960. By 1964, he was the commander in chief of his country’s 500-man army and its first colonel. Two years later, he overthrew the Central African Republic’s civilian president and embarked on a long period of erratic and power-hungry rule.

Books in review

Slow Poison: Idi Amin, Yoweri Museveni, and the Making of the Ugandan State

Buy this bookThis culminated in Bokassa’s self-proclamation as the country’s president for life, and then even more grandiosely in 1977 as imperial majesty of a newly renamed realm that he dubbed the Central African Empire. Throughout this rise, Bokassa’s superpower had been knowing how to ingratiate himself with the French. He granted France—as well as the United States, the Netherlands, and Israel—control of Central Africa’s diamond trade. He also hosted private game-hunting outings with France’s then-president, Valéry Giscard d’Estaing. In fact, their relations became so close that Giscard d’Estaing called Bokassa “a friend and family member.”

France, in turn, helped underwrite Bokassa’s lavish coronation as the newly minted emperor of a poor country. It was reputed to cost a third of the national budget, and French artists and jewelers helped with designs for the ceremony and regalia, said to be modeled after Napoleon’s. The French Navy orchestra even helped support the band that played at the crowning.

Bokassa’s utility to France soon proved to have a limit, though. His government’s violent suppression of student riots caused France to weaken its support for a regime that it had so recently propped up. And when Bokassa responded by flirting with new foreign allies, including Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi, France backed a successful coup to overthrow him in September 1979.

Soon afterward, the French pictorial weekly Paris Match ran an explosive report claiming that Bokassa was a cannibal, including photos that purported to show the refrigerator where he stored the bodies of victims awaiting consumption. This was just months before I moved to West Africa fresh out of college in December 1979, but it initiated another kind of education for me: one about the readiness—or, better, zeal—of the Western press to traffic in the worst stereotypes of African primitivism and savagery on the flimsiest of pretexts.

Bokassa was by no means a wise or even passingly good leader, but the story about his cannibalism seems to have been nothing more than that: a narrative promoted by France after it decided to disencumber itself of him and then eagerly spread by the international media. Although Bokassa was eventually tried publicly for a variety of crimes in Central Africa, he was never convicted of the consumption of human flesh. When I interviewed him in the capital, Bangui, in 1996, he serenely rebutted the accusation and said, “I would prefer not to pass judgment on my own rule. That is for the Central African people, and I would invite you to ask them about me.” Years later, even though the taint from this never-proven charge persisted in the West, he was posthumously rehabilitated in his own country, where he was called a “son of the nation” and recognized as a “builder.”

Recently, I was reminded of Bokassa while reading a serious and compelling contrarian depiction of an equally infamous African leader of the same era: Uganda’s Idi Amin. Like Bokassa, Amin was a power-hungry opportunist who reveled in the theatrical and sometimes absurdly comic possibilities of authoritarian leadership in a newly independent but skeletal state. As Bokassa had been with France, Amin was initially a protégé of his country’s former colonizer, Britain, and then became a thorn in its side. By a remarkable coincidence—or was it?—he, too, was slandered as a cannibal during London’s concerted effort to overthrow him for what were mostly geopolitical reasons.

Amin and the Ugandan dictator who succeeded him, Yoweri Museveni, are the twin subjects of a new book, Slow Poison, an extraordinary work of postcolonial history by the eminent Ugandan American scholar Mahmood Mamdani. Mamdani declares his book’s biggest challenge at the very outset, when he asks the reader to shed media-driven preconceptions about Amin as a cartoonish and tyrannical buffoon, even a sort of African Hitler, albeit one whom Western portrayals have rendered in comic tones steeped in the worst racial stereotypes of Africans. Mamdani immediately makes clear how high the stakes are in this revisionism, not only by challenging the prevailing Western narrative about Amin but also by undermining what has become a stock depiction of his treatment of the country’s South Asian population, whose mass expulsion he ordered in 1972. Here, the standard narrative has been one of Black racism coupled with rampant brutality and venality.

Mamdani’s credentials on this subject go far beyond the merely academic. His own ethnically Indian family were members of this expelled class, and the author himself later returned to the Uganda that he has always considered home. Amin, he writes, “invited his adversaries to underestimate him, even to think of him as a buffoon. His rhetoric included Hitlerite proclamations (including actual praise of Hitler), but that was not the same as committing Hitlerite atrocities. The Asian expulsion is said to have been a Hitlerite act. Yet, as we shall see, even as Amin ethnically cleansed Uganda of Asians and expropriated them, he did everything in his power to spare Asian lives.”

Getting us to reconsider Museveni, the book’s other central figure, is a more subtle challenge, but by no means a simple one, given the decades of support the United States has provided to Amin’s successor, a corrupt and unprincipled, dyed-in-the-wool authoritarian who seems bent on fulfilling the Bokassa dream of ruling his country for life. Yet taken together, Mamdani’s bracingly contrarian portraits of Amin and Museveni provide strong grounds for a long-overdue reappraisal of the two men, not on the basis of the geopolitical needs and racial fantasies of the West, but in light of their own records.

Mamdani begins his book with a careful examination of how Amin overcame difficult origins. He hailed from a loose and disadvantaged multiethnic cluster in the north of Uganda known as the Nubi. Driven by the shabby, pseudoscientific notions that were common in the 19th and early 20th centuries, Frederick (Lord) Lugard, a major figure in British colonial history, had identified the Nubi as “the best material for soldiery in Africa,” and Amin soon entered this profession. In 1939, at the age of 11, he began working in the kitchen on a seafaring ship serving the King’s African Rifles, a British colonial army. By the age of 18, Amin had been inducted into the Rifles. According to one account, this was the result of a chance encounter: Working as a bellboy at the Imperial Hotel in Kampala, Amin approached a Scottish officer and declared his interest in becoming a colonial soldier. “All right, jump in the truck,” the officer is said to have responded, noticing the then-17-year-old’s strapping physique and facial scars typical of Lugard’s description of this martial race.

After completing a training course in 1957, Amin was catapulted to the rank of affande, or officer, in 1959, the highest then available to an African. That very day, he exhibited the kind of defiant attitude toward domination by whites that would long characterize him: “Amin walked past the sergeants’ mess, where he was expected to go as a Black officer,” Mamdani writes, “and instead strode straight into the ‘Whites Only’ officers’ mess in the 1st Battalion and ordered a drink.” When the bartender refused to serve him, “Amin pulled him over the counter and landed a sharp right on the Englishman’s chin. The room full of white officers were shocked into hushed silence. In a few days, the authorities scrapped the rule and the officers’ mess was desegregated.”

Amin soon distinguished himself in other ways that impressed the British, notably in his use of brutality in the late-colonial counterinsurgency campaigns that he was assigned to against the pro-independence Mau Mau uprising in neighboring Kenya and elsewhere. “Terror, he was taught, was a legitimate weapon so long as you achieved your assigned objective,” Mamdani notes, and mastering this lesson assured Amin’s continued rise. In 1961, the British promoted him to lieutenant, the highest rank of any African in the army, and the following year to captain, just three months before Uganda’s independence.

Just as Bokassa had been for France, the British-trained Amin became an attractive solution for London in maintaining its neocolonial control over Uganda. The country’s early post-independence leader, Milton Obote, had turned toward socialism and dictatorial rule in the late 1960s, a time of rampant corruption and food shortages. But when Amin seized power in 1971, overthrowing Obote’s government while Obote was attending a Commonwealth conference in Singapore, he promptly toed the British line on foreign policy, notably in calling for “reconciliation” with the apartheid government of South Africa.

This fueled widespread and lasting speculation that Britain had helped organize or at least supported Amin’s takeover. Others, too, had motives. Mamdani’s book supports the long-standing view that Israel played an important role, either alone or in loose concert with Britain. As I documented in my own book The Second Emancipation, Israel maintained a highly active foreign policy in Africa in the 1960s. Its interest in Uganda, according to Mamdani, was due to its “periphery doctrine,” under which Israel sought to build partnerships with states bordering the Arab world.

As the southern neighbor of Arab-dominated Sudan, Uganda fit this bill, and Mamdani builds a case that during his time as commander of the Ugandan Army under Obote, Amin ferried Israeli supplies to a rebel group in South Sudan known as the Anyanya. Mamdani also notes that Israeli intelligence operatives later warned Amin of Obote’s plans to sideline him and then actively advised Amin on how to seize power. These circumstances, if not proof in themselves, certainly favor a conspiratorial view. Either way, once he was in power, Amin did appear more open to British and Israeli interests than he might have been otherwise. When he made his first overseas trip, it was to Israel, and around this time he also rejected criticisms by other African nations of Britain’s arms sales to South Africa. Those vehemently opposed, he said, should “give priority to putting their own house in order.”

But while it seems likely that Amin’s rise to power was aided by Britain and Israel, his relations with both countries fell apart with remarkable swiftness. The proximate cause from the Ugandan side seems to have been Amin’s frustrations with the limited arms supplies and other military support they provided to secure his rule and thwart a threatened invasion from Tanzania, where Obote had established himself along with a significant portion of the Ugandan Army.

By early 1972, Amin had radically retooled his foreign policy, completing a rapprochement with Arab states that had been engineered by Libya and denouncing British support for minority white rule in southern Africa. That March, Israel announced the withdrawal of its military experts from Uganda, after which Israeli diplomats and businesspeople were asked to leave the country. “From here on, Israel would look for ways to effect a regime change in Uganda,” Mamdani writes.

Press reports at the time began to depict Amin as a gullible dupe of Gaddafi. In Mamdani’s portrayal, though, however unsavory his rule became, Amin was no ignoramus, but rather a shrewd and deliberate politician who reveled in turning the tables on his antagonists. He incorporated the Anyanya into his own army to defend against Obote. He won support from the Arab world to replace much of what he had lost from Israel. And he made a particular sport of humiliating the British, just as colonial rule had demeaned Africans.

Bokassa had wounded France’s amour propre by revealing how susceptible its politicians were to the corrupting blandishments of supposedly inferior Africans. France went so far as to order the destruction of the entire print run of a Bokassa memoir in which he claimed to have arranged sex with local girls for Giscard d’Estaing during their safaris together. Likewise, Amin’s revenge took other, more theatrical forms. In 1972, for example, during a British economic crisis, he asked his countryfolk to donate whatever they could to the former colonizer. People came to the airstrip designated for this aid with goats, chickens, maize flour, and groundnuts. In 1975, when Britain sent its foreign secretary to Uganda to secure the release of a citizen who had criticized Amin as a “village tyrant,” the British official was forced, Mamdani writes, “to ‘bow’ to enter a ‘hut’ with a low entrance, a gesture Amin had televised and broadcast.”

After Amin’s downfall, Britain’s then–foreign secretary, David Owen, likened him to Pol Pot for the alleged scale of the bloodletting in his country, but Mamdani finds scant basis for this comparison. He notes that the single largest atrocity committed under Amin, a barracks massacre during the overthrow of Obote, implicated both the British and the Israelis, whom he says encouraged it. Although Amin’s regime engaged in plenty of corruption, Mamdani contends that Amin was not personally venal, and that his government, though often slapdash, was not bereft of merit. Although Amin exempted himself from its judgment, he created one of the world’s first truth commissions to investigate the growing number of civilian “disappearances” in Uganda, and he saw to it that the expulsion of South Asians from the country was “orderly and humane, without a free-for-all of theft by the military.”

Mamdani’s portrait of Museveni stands in sharp contrast to his portrait of Amin. Museveni had entered the power sweepstakes in Uganda in the early 1970s as the head of one of the military insurgencies aiming to overthrow Amin. In the end, a larger group led by the former president, Obote, who was strongly backed by Tanzania and Britain, prevailed. But after claiming that Obote had rigged the national elections in 1980, Museveni and his fighters returned to the fray, plunging the country into a renewed civil war that they ultimately won. My first visit to Uganda was during the terrifying final months of Obote’s rule in 1984, when extrajudicial executions and disappearances were rife. Mamdani, then unknown to me, was a university instructor, someone deeply plugged in to the turbulent political scene in the capital and the surrounding region.

When the Museveni-led insurgency finally seized power in 1986, Museveni espoused a vaguely progressive third-worldism—but Mamdani, who knew him in these early days and has encountered him repeatedly since, says that any idealism Museveni might have possessed quickly gave way to a strategy of unprincipled survivalism. He emerges in Mamdani’s book as a kind of East African Machiavelli whose politics gradually boiled down to a simple essence: Stay on the right side of the United States by servicing its regional national-security needs and embracing its global economic strategies in general. Whereas Amin had incarnated the rebellious former acolyte, aiming his calculated taunts at the West, Museveni instead played the good pupil, someone who repeatedly ingratiated himself with the West in order to secure his own interests and those of his closest followers.

After gaining power, Museveni initially sought economic help from the socialist world. But when this was not forthcoming, he wholeheartedly embraced—in a turnabout as dramatic as Amin’s shift in foreign policy—a program of structural adjustment and privatization of public assets pushed by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. This helped enrich the people in Museveni’s circle of power but enfeebled the state itself, turning its ministries into “ghost institutions” and weakening their role in many basic services, such as healthcare and education. Had this led to an economic takeoff, as the so-called Washington Consensus predicted, it might have been an acceptable outcome, but divestment in this case proved instead to be a dead end for national development.

Lacking the means to develop his country further, Museveni busied himself as a regional warlord instead. This began, Mamdani writes, with his crucial support for the Tutsi rebel forces that seized power in neighboring Rwanda following the anti-Tutsi genocide there in 1994. Since then, Museveni has repeatedly turned to the armed pillaging of Congo, Uganda’s western neighbor, and its vast resources. This began alongside Rwanda and Uganda’s successful joint efforts to invade Congo and overthrow its longtime dictator, Mobutu Sese Seko, in a war that I covered for The New York Times. Informed speculation has long held that this war was prosecuted with the encouragement and support of the United States.

Rwanda and Uganda invaded Congo a second time in 1998 to overthrow Mobutu’s successor, Laurent-Désiré Kabila, who quickly shifted from being a pawn of his neighbors to a truculent and independent-minded actor. Along the way, however, something unexpected happened: The invaders fell out violently over a division of the spoils, which consisted of their much larger neighbor’s rich stores of gold, diamonds, and coltan, a scarce mineral vital to the manufacture of cell phones.

Bit by bit, by fomenting instability in the region, Museveni had begun to turn into a nuisance for some Washington policymakers. The Ugandan Constitution limited the presidency to two terms, and in the 2000s, Mamdani notes, citing the work of the journalist Helen Epstein, that the US ambassador, Jimmie Kolker, told Museveni to withdraw his forces from Congo and prepare a credible transition at home. “Retire from office in 2006,” Kolker reportedly said, “and we’ll help find you lucrative work as a UN negotiator.”

But the ever-resourceful Museveni found a way to reinvent himself once again. To elude any constraints on his behavior at home, Mamdani continues, Museveni “offered to join the global War on Terror in return for an assurance of impunity.” In practice, this has meant becoming America’s expeditionary proxy, which began with an offer to help the United States in its war against the Islamic militants of al-Shabaab in Somalia.

By this time, Museveni had presided over not only the looting of Congo and the perpetuation of strife there, but also his government’s pilfering of money contributed by the United States to George W. Bush’s President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), as well as from a global fund to combat other diseases. Among those implicated, Mamdani notes, were Museveni’s brother, Salim Saleh, and Saleh’s wife.

The most recent instance of Museveni’s bending to the needs of Washington in order to preempt any scrutiny of his self-perpetuating rule came late this summer when he signaled to the Trump administration that Uganda would accept people deported from the United States, irrespective of where they came from.

Had the United States taken Museveni at his word, none of this would have come as a surprise. Mamdani writes that the Ugandan leader felt so confident in his approach to power—and in his support from the West—that he publicly stated, in 2022, that “there was nothing wrong with official corruption so long as the beneficiaries kept the loot within the country.”

When Museveni took over as Uganda’s president, he announced in his inaugural address, “The problem of Africa in general and Uganda in particular is not the people but the leaders who want to overstay in power.” Now he seems to be openly testing the proposition that establishing family rule over Uganda—think Central Africa’s Bokassa without an imperial coronation—will face no serious opposition overseas so long as the state can continue to find new ways to service the needs of the United States or the West more generally. Museveni’s 51-year-old son, Muhoozi Kainerugaba, who is commander of the armed forces, has made plain his intention to succeed his eightysomething father. In a post on X in July, he said, “In the name of Jesus Christ my God, I shall be President of this country after my father!” The Wall Street Journal reported that Kainerugaba had taken to social media that month to brag about the torture of Edward Ssebuufu, the bodyguard of Uganda’s main opposition leader. Ssebuufu said that he was beaten in the groin with a baton, waterboarded, and electroshocked. Kainerugaba has trained at the US Army’s Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and the British Royal Military Academy Sandhurst.

The final contrast that Mamdani draws between Amin and Museveni involves their treatment of ethnicity, a topic that traverses nearly all of his writing and scholarship on Africa.

Mamdani has long contended that many of the entrenched divisions between ethnic and linguistic groups (often reductively referred to “tribes”) on the African continent today were manufactured by the colonizers for the purposes of administrative convenience and control. Yet no matter how recent or artificial its origins, this legacy has bedeviled many African nations from the earliest days of independence. The deadliest example is the civil war that Nigeria experienced. But at one time or another, such divisions and grievances based on notions of tribe have plagued the politics of much of sub-Saharan Africa in the postcolonial era.

This was also the case in Uganda, where Obote, Amin, and Museveni, in different ways, all mobilized support along ethnic lines. Embracing a racially based nationalism and, at times, pan-Africanism, Amin sought to paper over the differences between Uganda’s British-defined tribes, and yet he did so, in part, by casting the country’s South Asian citizens as an alien “tribe” to be expelled from the new Uganda. Mostly the descendants of people who had been brought to the country as indentured servants by the British, they served as an obvious target for Amin’s racial populism, and in 1972, he expelled Uganda’s South Asian citizens and then seized and redistributed their property.

This was a dark period in Uganda’s postcolonial history, which Mamdani narrates with precision and detail. That he can write about such a traumatic episode with objectivity and scant emotion is remarkable, for Mamdani was one of the Ugandans expelled from the country by Amin. By a historical fluke, Mamdani was born in India, where his father (who was born in modern-day Tanzania) had gone to study. But in every other way, Mamdani had a normal Ugandan Indian upbringing in Kampala.

Indeed, when Uganda became independent in 1962, the young Mamdani went to the United States on a scholarship to become an engineer and help his country on its march toward the construction of a new nation. Studying at the University of Pittsburgh, he also became politicized there. Mamdani relates a chance encounter with recruiters for the Freedom Rides conducted by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and describes how he volunteered on the spot to travel with others by bus to Alabama to demonstrate on behalf of voting rights and an end to the segregation imposed on African Americans in the South.

Along with his experiences in his native Uganda, this seems to have further put Mamdani on a course toward an internationalist, anti-imperialist progressivism. But upon returning to Uganda, he found a very different country: Just as Mamdani was settling back into his life there, Amin embarked on his campaign against the country’s South Asian population.

The story of Amin’s expulsion of Ugandans of Indian and Pakistani descent received enormous coverage in the West at the time, and this injustice became a principal justification for Britain in its drive to overthrow him. But as rigorous as Mamdani is in his treatment of this topic, and despite his own close proximity to this part of the story, he is no less careful to note that no matter what one makes of Amin’s misrule, what followed was at least as troubling, even if it never captivated the imagination or the attention of the international press. For in the aftermath of Amin’s overthrow, another kind of misrule took hold in Uganda, one bent strongly toward the appeasement of Western interests in East Africa while skimping on the public-welfare needs of Uganda’s citizens and rigging the country’s electoral system to eliminate any real competition.

The British had helped create Amin and opened up the space for him to eventually take power. When they wearied of him, they then supported his overthrow, much as France had done with Bokassa. But it was the United States, after Museveni finally took over, that gradually became the most important foreign architect and sponsor of a regional order in East Africa. Unable to cobble together a coalition of ethnic groups to perpetuate himself in office, Museveni pursued a continuation of the British colonial divide-and-rule strategy. Remarkably, as Mamdani writes, this has meant creating ever more tribal identities in Uganda, exploding established groups into finer and finer subgroups, each with its own local political and property rights, in order to sustain his rule. By promoting a narcissism of small differences on a district-by-district basis, Museveni has, Mamdani posits, made it all the more difficult for any figure with national credibility to emerge and challenge his power.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →By the end of Slow Poison, one realizes much more than the narrow fact of the Western media’s frequently ideologically driven treatment of Africa, which has a shallowness far beyond its coverage of most other parts of the world. This is only the first—or the most immediate—target of the bold revisionism that Mamdani’s history offers. More important is the way the author reveals how Africa policy in Washington, and in former imperial capitals like London and Paris, remains dominated by short-term calculations and impulses—quick, cheap fixes that pay little heed to understanding the countries these Western power centers easily manipulate and that make little genuine effort to take into account the needs of their populations or, indeed, of democracy.

This was as true of Britain’s promotion of Amin during his rise to power and France’s support for Bokassa in Central Africa, each in an earlier era, as it has been of the United States’ unstinting but see-no-evil support for Museveni. And it holds just as well for Western support of rulers in any number of other African states. Rwanda under Paul Kagame is perhaps the best current example. There, Washington and its European allies have supported a ruthless and domineering authoritarian in the belief that by ruling over his country tightly, Kagame offers the best insurance policy against a resumption of chaos and widespread violence.

Ultimately, though, the lesson one derives from Slow Poison is that authoritarians who perpetuate personal power inevitably hollow out their countries’ institutions and create vacuums when they die or are overthrown. Any stability they seem to provide is illusory. Someday, Kagame will disappear, and in the inevitable void, then what? In the case of Museveni, by steadily heightening the importance of ethnic identity, he seems to have been piling up the gunpowder that may only take a small spark to ignite someday. If that turns out to be the case, so much for the convenience of the Western local proxy or strongman.

More from The Nation

Jared Kushner’s “Plan” for Gaza Is an Abomination Jared Kushner’s “Plan” for Gaza Is an Abomination

Kushner is pitching a “new,” gleaming resort hub. But scratch the surface, and you find nothing less than a blueprint for ethnic cleansing.

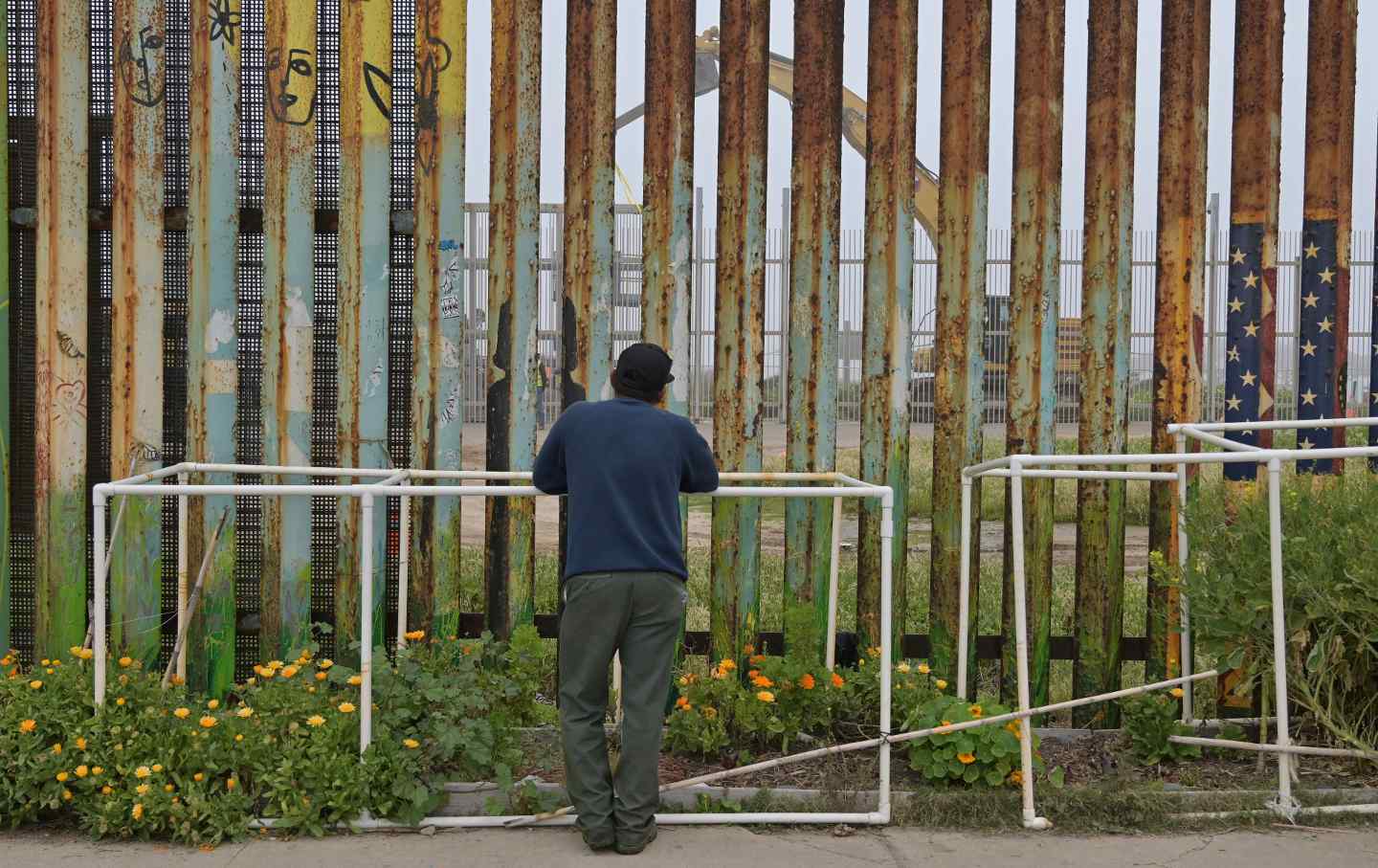

I’ve Covered Migration and Borders for Years. This Is What I’ve Learned. I’ve Covered Migration and Borders for Years. This Is What I’ve Learned.

Borders are both crime scenes and crimes, with nationalism the motive.

Gaza Is a Crime Scene, Not a Real Estate Opportunity Gaza Is a Crime Scene, Not a Real Estate Opportunity

The Trump administration’s plan for a New Gaza has nothing to do with peace and rebuilding, and everything to do with erasure.

Mark Carney Knows the Old World Is Dying. But His New World Isn’t Good Enough. Mark Carney Knows the Old World Is Dying. But His New World Isn’t Good Enough.

The Canadian prime minister offered a radical analysis of the collapse of the liberal world order. His response to that collapse is unacceptably conservative.

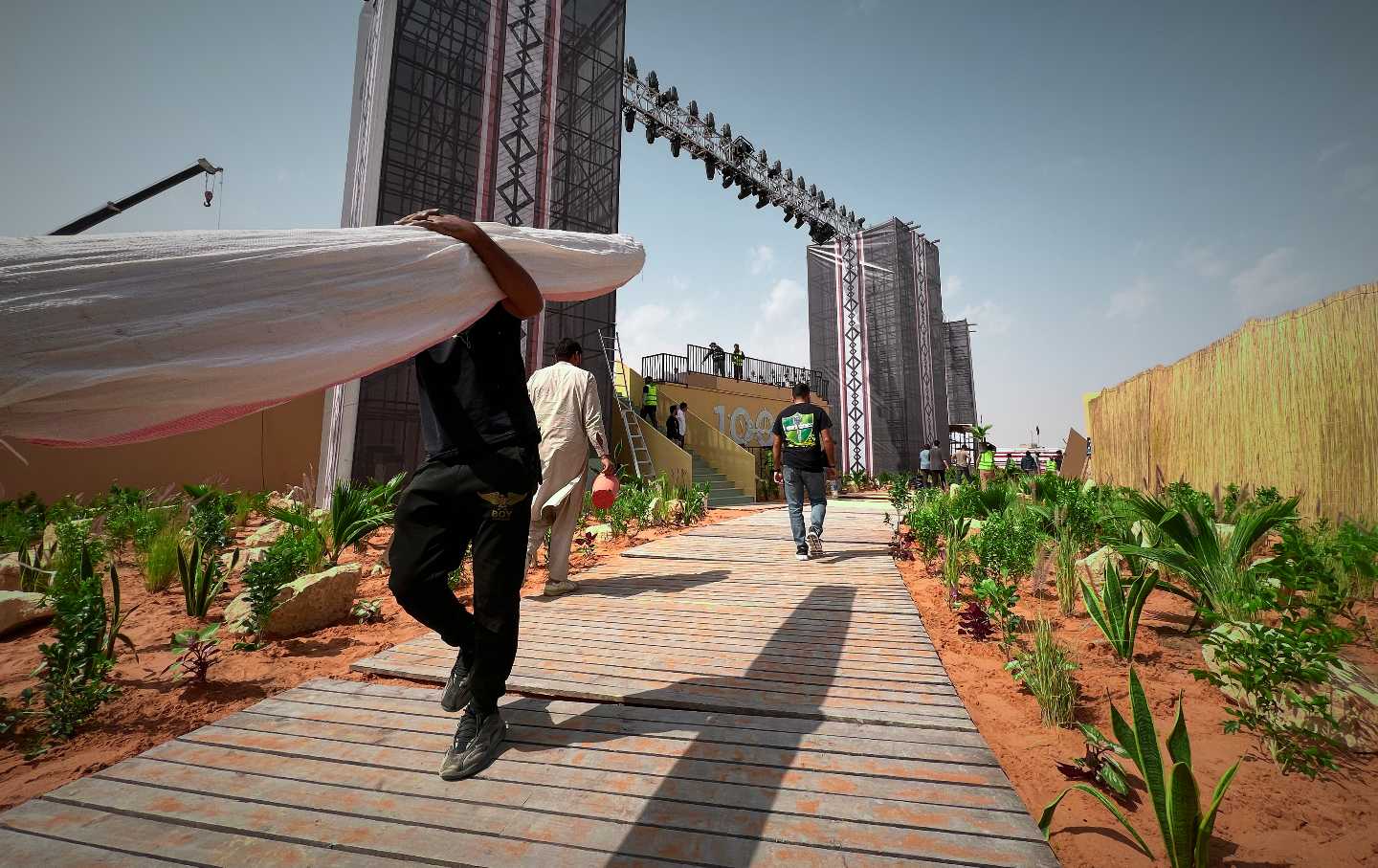

The Line, a Saudi Megaproject, Is Dead The Line, a Saudi Megaproject, Is Dead

It was always doomed to unravel, but the firms who lent their name to this folly should be held accountable.