Let Me Live

The Angelo Herndon case and the radical politics of free speech.

Angelo Herndon and the Radical Politics of Free Speech

The story ofhis landmark case reminds us of how powerful a popular front of socialists and liberals can be in protecting our civil liberties.

Racism has often accompanied the repression of civil liberties. In the antebellum period, the defenders of slavery criminalized teaching the enslaved to read or write; banned the voicing of antislavery sentiment in colleges; prohibited the distribution of antislavery literature through the mails; and proscribed consideration of antislavery petitions in Congress. Militant foes of abolitionism destroyed presses and assassinated editors. A mob dragged William Lloyd Garrison, the editor of The Liberator, through the streets of Boston, while another temporarily silenced abolitionism’s greatest orator, Frederick Douglass, who later remarked aptly that “slavery cannot tolerate free speech.”

Books in review

You Can’t Kill a Man Because of the Books He Reads: Angelo Herndon’s Fight for Free Speech

Buy this bookIn the long, terrible period of racist reaction that followed Reconstruction, proponents of white supremacy continued to try to stifle anti-racist dissent. In 1892, in Memphis, they destroyed the press of the indomitable anti-lynching journalist Ida B. Wells and threatened to kill her if she returned to her home there. During World War I, the federal government prosecuted and imprisoned the editor G.W. Bouldin under the Espionage Act because his newspaper published a letter that supported a protest organized by Black soldiers in response to the police beating of an African American corporal, Charles Baltimore. During the McCarthy era, racists used the Red Scare to isolate racial-justice activists on the left, such as W.E.B. Du Bois and Paul Robeson, whose passports were canceled to prevent them from offering opinions abroad that the US secretary of state deemed injurious to the country. During the Second Reconstruction in the 1950s and ’60s, white supremacists sought to squelch dissent by outing members of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in areas where a known affiliation would cause the loss of employment, the withdrawal of credit, or threats of violent retribution. White supremacists schemed to prevent civil-rights lawyers from attracting clients, to afflict news media with ruinous libel judgments, to condition funding and certification for colleges on the ejection of political mavericks, to spy on groups such as the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and to surreptitiously disrupt organizations like the Black Panther Party. More recently, anger, fear, and resentment occasioned by the elevation in the status of African Americans has fueled efforts to prohibit the teaching of “critical race theory,” to erase information in national parks about the history of slavery, and to remove “divisive” books from libraries.

Brad Snyder’s You Can’t Kill a Man Because of the Books He Reads revisits one of the more dramatic episodes in this ongoing saga of repression and resistance: the story of Angelo Herndon, a young, Black communist organizer who was prosecuted in Georgia in 1932 for attempting to incite an insurrection, sentenced to imprisonment after an egregiously unfair trial, and then freed after a nationwide campaign by civil libertarians and anti-racist activists that occasioned two trips to the Supreme Court and an important vindication of First Amendment freedoms. Snyder’s excellent book is both inspiring and sobering. It portrays vividly the exertions of a wide range of people who rallied to save Herndon. But it also reminds us of the relative recency of this judicial solicitude for the freedom of expression as well as the instability of that protection.

Angelo Herndon was born into a sharecropping family in Bullock County. Alabama, on May 6, 1914. He attained only about a sixth-grade education before poverty pushed him into work at a series of menial, back-breaking, dangerous jobs mining and shoveling coal.

In 1930, in Birmingham, Herndon attended a meeting of the Unemployed Council, a communist organization that encouraged white and Black workers to cooperate in demanding “economical equality” and an end to racial tyranny. Hooked immediately, he began reading communist tracts and attending demonstrations. He joined the Young Communist League and became a full-time organizer for the Trade Union Unity League. For seeking to educate and mobilize workers, Herndon became a target of the police and was repeatedly arrested, convicted of vagrancy, and incarcerated. In an effort to help him escape the harassment, his seasoned comrades sent him to Atlanta. His enthusiasm, however, soon prompted him to organize the demonstration that led to the landmark ruling that bears his name: Herndon v. Lowry.

In June 1932, the precocious Herndon, then just 18, printed 10,000 leaflets calling for people to protest a recent decision of the Fulton County Board of Commissioners to stop funding relief for the poor. The header of the leaflet was striking for its invocations of class, race, and gender:

WORKERS OF ATLANTA!

EMPLOYED and UNEMPLOYED—

Negro and White—ATTENTION!

MEN and WOMEN OF ATLANTA

Repudiating the Deep South’s Jim Crow etiquette, Herndon ventured boldly: “If we allow ourselves to starve while these fakers grow fat off our misery, it will be our own fault.”

On the appointed day, about 150 people gathered. A county commissioner agreed to meet, but only with the white protesters. The next day, the Fulton County Board modestly increased unemployment relief. Soon thereafter, the police detained Herndon, searched his rented room without permission or a warrant, and seized his books and pamphlets. Then they took him to a police station, where they beat him, strapped him into a fake electric chair, and tried to elicit a confession from him, though they refused to tell him why he’d been arrested. The police held Herndon incommunicado for 11 days before finally charging him with attempting to incite an insurrection.

The authorities did not allege that Herndon had engaged in violence or had prompted others to be violent or engage in any immediate lawbreaking. Instead, they staked their case on Herndon’s admitted membership in the Communist Party, his recruitment on its behalf, his dissemination of communist polemics such as George Padmore’s The Life and Struggles of Negro Toilers, and the party’s stated ambition of supplanting the US government with a communist regime that intended to create a territory in the South governed by Black folk. The theory of the Georgia prosecutors was that these actions amounted to illicit preparation for an eventual revolution.

Racism pervaded Herndon’s tribulations. The statute under which he was prosecuted was enacted in 1833 to protect “Negro slavery” from the “danger” of rebellion. Racial discrimination deformed the selection of his juries: Officials typed the names of prospective white jurors on white cards and the names of prospective Black jurors on pink or yellow ones. Herndon was indicted by an all-white grand jury and convicted by an all-white petit jury. Asked to explain the racial homogeneity of the grand jury, officials stated that they’d selected only “the most intelligent, upright citizens” and that on that basis there were simply no eligible Black people available. Such discrimination stretched far beyond Herndon’s case; no one could recall an African American serving on any jury in the county. Yet Herndon’s trial judge rejected claims of illicit racial exclusion.

Herndon’s defense team featured a rarity in 1930s Georgia: an African American attorney. Benjamin Davis Jr., the privileged son of the publisher of the Atlanta Independent newspaper, had attended Amherst and Harvard Law School, where he roomed with William Hastie (who later became the country’s first Black federal judge) and Robert C. Weaver (who later became the country’s first Black cabinet secretary). Upon Davis’s return to Atlanta from Harvard, he was something of a dandy, drawn to tailored suits and spats over patent leather shoes. But when he read a newspaper account of Herndon’s arrest, he went to the city jail and offered his legal services pro bono.

The International Labor Defense, which at the time was overseeing many civil-rights cases as well as much of the country’s legal representation for communists, liked the prospect of a Black defense counsel, especially one who wasn’t charging a fee. But Davis had never argued a criminal case before, and so the ILD tried to obtain more experienced counsel. It briefly retained a respected local white attorney but he withdrew after refusing to challenge the legitimacy of a jury selection in which only white citizens had been chosen. The ILD then turned to Atlanta’s most prominent Black attorney, A.T. Walden, but he demurred, concerned that the organization would try to dictate legal strategy.

Thus Davis, inexperience notwithstanding, became Herndon’s main trial attorney, and he endured racist threats throughout the trial. One morning, leaving his house, Davis discovered a white cross bearing the note “The Klan Rides Again. Get out of the Herndon case. This is a white man’s country.” On other occasions, spectators accosted him, making their sentiments known in unmistakable terms: “Watch yourself, or we’ll string you up.” More upsetting to Davis was the trial judge’s failure to maintain even a minimal level of decorum in the courtroom. When prosecutors referred to Herndon as a “nigger,” Davis immediately objected. The judge told the prosecutors to stop using the slur, but they continued to do so anyway with virtual impunity.

“If you don’t send this defendant to the electric chair,” one prosecutor told the jury, “we will have a Red Army marching through Georgia which will take all of the land away from the white people and give it to the Negroes!”

Herndon declared, by contrast, that the government could imprison or kill him and hundreds of other dissidents, but that repression “will never stop these demonstrations on the part of Negro and white workers who demand a decent place to live…and proper food for their kids.” Herndon’s counsel added that his client’s only “crimes” were his skin color and his daring to ask for assistance for the impoverished. As for the communist literature, Davis maintained: “You can’t kill a man because of the books he reads.”

After the jury handed down its foreordained verdict, a broad range of observers rallied around Herndon. Communists sought to use his conviction as a basis for revealing the perfidy of a capitalist system that deployed race to confuse and divide the working class. Liberal racial reformers perceived his persecution as yet another instance of naked racial oppression.

Another key contingent of supporters were the lawyers appalled by Georgia’s disregard for due process and its attempted nullification of the rights to read, speak, and organize freely. While some of these attorneys were anti-racists, others were white supremacists of the courtly, courteous, patrician variety. Uniting them was an abhorrence of government overreach, a fidelity to procedural consistency, and a respect for civil liberties. The most effective and essential of these attorneys was Carol Weiss King. A target of gross sexism and antisemitism, Weiss was a stalwart leftist who dedicated her career to the legal defense of radicals and immigrants. According to Snyder, “There was no better brief writer, legal strategist, and recruiter of talented lawyers.”

King succeeded in enlisting a slew of impressive attorneys to assist in Herndon’s defense. Whitney North Seymour was the youngest partner at the venerable law firm of Simpson Thacher & Bartlett. A graduate of Columbia Law School, an alumnus of the US solicitor general’s office (where he argued 35 cases for the United States before the Supreme Court), an up-and-coming leader of the New York State Bar, and a staunch civil libertarian, Seymour agreed to represent Herndon, but only on the condition that he would be free from interference by the communists in terms of his litigation strategy. Walter Gellhorn and Herbert Wechsler were both former law clerks to Supreme Court Justice Harlan Fiske Stone and members of the faculty at Columbia Law School. Elbert Tuttle was a past president of the Lawyers Club of Atlanta and the commander of the Fulton County American Legion Post.

Judges were also essential to saving Herndon. Two were especially pivotal: Hugh M. Dorsey and Owen Roberts. Dorsey was the judge who granted Herndon habeas corpus relief after the Supreme Court rejected his initial appeal. He ruled that the law under which Herndon had been convicted was “too vague and indefinite to provide a sufficiently ascertainable standard of guilt.” Although the Georgia Supreme Court later reversed this decision, Dorsey’s ruling kept Herndon’s federal constitutional claims alive; without his action, Herndon would likely have been condemned to a long stretch of body- and soul-destroying imprisonment.

Dorsey’s own backstory was complicated. He was a former prosecutor who rose to prominence by convicting Leo Frank, the Jewish superintendent of a pencil factory at which a 13-year-old worker, Mary Phagan, was raped and killed. Dorsey delivered a summation to the jury that spanned nine hours over three days and exploited an atmosphere suffused with anti-Jewish prejudice in order to win his conviction.

After Frank was sentenced to death, his lawyers petitioned the US Supreme Court, claiming that his trial had violated the norms of due process. The court rejected this argument 7–2, and Frank appealed to Georgia’s governor, who commuted his sentence to life imprisonment. Frank’s relief, however, was short-lived: Outraged residents of Phagan’s hometown abducted Frank from a state prison and lynched him.

Though history would judge this dark episode quite differently, Dorsey was lauded at the time by white voters for obtaining Frank’s conviction, and he successfully ran for governor and served two terms. But then a strange thing happened: He became a vocal critic of racist violence. Dorsey decried lynchings and other aggressions against African Americans, noting that “in some counties the Negro is being driven out as though he were a wild beast.” The facts, he asserted, indicted Georgia “more severely than men and God have condemned Belgium and Leopold for the Congo atrocities.”

Although Dorsey’s extraordinary rebuke put an end to his career in electoral politics, he subsequently received judicial appointments, one of which provided the platform from which he was able to resuscitate Herndon’s appeal. It was Tuttle, the Atlanta attorney, who intuited that Dorsey’s lingering feelings of guilt might incline him toward sympathy for Herndon.

In the US Supreme Court’s first review of Herndon’s conviction, the court affirmed it 6–3, with Justices Harlan Fiske Stone, Benjamin Cardozo, and Louis Brandeis in dissent. But in the court’s second review, it reversed after Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes and Associate Justice Owen Roberts changed their votes. The latter wrote the opinion for the majority; in it, he asserted that the facts adduced at trial failed to support the theory of criminal insurrection that the prosecution had set forth. “The only objectives appellant is proved to have urged,” the opinion stated, “are those having to do with unemployment and emergency relief which are void of criminality…. In these circumstances, to make membership in the [Communist Party] and solicitation of members for that party a criminal offense, punishable by death…is an unwarranted invasion of the right of freedom of speech.”

The ruling also maintained that the statute that had given rise to Herndon’s prosecution was unconstitutionally vague, amounting “to a dragnet which may enmesh any one who agitates for a change of government if a jury can be persuaded that he ought to have foreseen his words would have some effect in the future conduct of others.”

Roberts is often disparaged as the justice who switched his vote on the constitutional validity of New Deal initiatives in order to preempt proposed legislation that would have enabled President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to appoint a new justice for every incumbent who retained his seat after turning 70. Roberts’s change of heart is derided as “the switch in time that saved nine.” Yet Roberts had in fact changed his position on economic regulation before FDR announced the “court-packing” proposal.

Furthermore, in a variety of cases involving repression, Roberts had distinguished himself as an ally of freedom. He voted to overturn the conviction of Yetta Stromberg, who was prosecuted in California in 1931 for flying a red flag that was said to represent a prohibited “sign, symbol or emblem of opposition to organized government.” That same year, in Near v. Minnesota, he voted to invalidate a law that had been used to impose a prior restraint on a newspaper. Later, in 1944, with the war against Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan still raging, Roberts was one of the three dissenting justices who, to their everlasting credit, refused to uphold the constitutionality of detentions based solely on Japanese ancestry. Snyder rightly argues that Roberts’s crucial vote in Herndon was no fluke; it reflected a cultivated independence.

The subsequent stories of themany participants in the Herndon case are full of ironies, vindications, and tragedies. Herndon himself became one of the most prominent African Americans of the 1930s because of the campaign to save him. He addressed thousands at a rally in Madison Square Garden; wrote a critically acclaimed memoir, Let Me Live; and became friends with Richard Wright and Ralph Ellison. For a moment, it seemed as though he might forge a productive career as a literary activist. Herndon founded an ambitious journal, The Negro Quarterly, and also succeeded in distancing himself from the communist movement that had played such a dominant, formative role in his life. The party had supplied him with an inspiring goal; it had given him a lens through which to make sense of things; and it had provided him with comrades. But Herndon became disillusioned with his revolutionary church because of its suffocating insistence on conformity to Stalinist orthodoxies.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Herndon’s break with the party was unfortunately accompanied by a recurrent vice that eventually ruined him: a financial impropriety that devolved from simple negligence to deceit and exploitation. Snyder notes that in 1954, “Herndon’s days of playing fast and loose with other people’s money finally caught up with him” after he sold the same apartment building to five different buyers.

Charged with various crimes, Herndon inspired a headline in Jet Magazine that read “Swindle Suspect Identified as Ex-Red Angelo Herndon.” After spending several years in Joliet State Prison, Herndon rejoined the party but would never realize his promise or attain his former prominence. When he died at age 83 in December 1997, not a single newspaper published an obituary.

Sad, too, was the trajectory of Benjamin Davis. Disgusted by the mistreatment heaped upon his client, Davis became a communist himself. After Herndon’s conviction, Davis moved to New York City, where he rose to the party’s highest echelons and also succeeded in local electoral politics, winning a seat on the New York City Council representing Harlem.

But Davis also suffered a series of setbacks. His loyalty to the party line, whether praising Stalin’s show trials in the 1930s or Nikita Khrushchev’s invasion of Hungary in 1956, required betraying the best of the values he had bravely championed in his defense of Herndon.

He also suffered under the United States’ suppression of communism and left-wing activists in general. In 1948, along with 11 other top party leaders, Davis was charged with violating the Smith Act, which had criminalized advocating the overthrow of the government by force. The federal indictment was analogous to the state indictment under which Herndon had been prosecuted. But Davis received no relief from the Supreme Court: Unwilling to resist the powerful upsurge in anti-communist hysteria that gripped every aspect of American society in the early Cold War period, the court affirmed his conviction. Davis spent several years in prison, though he remained a committed communist, and was enduring the onset of yet another anti-communist prosecution when death overtook him in August 1964, at the age of 60.

Other protagonists in the case fared better. Carol Weiss King spent the remainder of her life as a crusading progressive attorney. A founder of the National Lawyers Guild, she also served as general counsel for the American Committee for the Protection of the Foreign Born. Whitney North Seymour became a president of the American Bar Association, cochaired the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, and served on the board of the American Civil Liberties Union. Herbert Wechsler pioneered the academic study of federal jurisdiction; drafted the Model Penal Code, which many states use as a template for their criminal law; was a longtime director of the American Law Institute; and successfully argued the landmark case of New York Times v. Sullivan, which created the federal constitutional doctrine that governs defamation litigation.

Elbert Tuttle delivered a score of sweeping and pioneering decisions as a judge on the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals during the Second Reconstruction. Viewed as a race traitor by white supremacists, he was praised as a hero by partisans of the civil-rights movement. In 1966, when Stokely Carmichael was charged with inciting a riot in Atlanta, Tuttle was among the judges who, citing Herndon v. Lowry, stopped the prosecution.

Snyder’s excellent excavation of the legal travails that enveloped Angelo Herndon shows that individuals committed to the vindication of civil liberties can sometimes prevail even in dire circumstances. Prompted by ardent advocates confronting the dreadful facts, the Supreme Court freed Herndon from the terrifying prospect of spending years on a chain gang and added crucial reinforcement to the essential limits on government power. A part of the legacy of that effort surfaces whenever a defendant invokes the Fifth Amendment’s due-process clause to challenge vague or improper laws or deploys the First Amendment to challenge government attempts to squelch speech because of ideological animus. As Snyder writes: “Generations of protestors from opposite sides of the political spectrum—civil rights activists and white supremacists, abortion rights and pro-life advocates, the Tea Party and Black Lives Matter, and pro-Israeli and pro-Palestinian demonstrators—stand on the shoulders of Angelo Herndon.”

But the story of what happened after Herndon’s case also serves as a reminder that no legal victory is complete or permanent. Herndon’s time in jail prior to his victory at the Supreme Court and Davis’s time in prison after his Supreme Court loss offer stark warnings. In Herndon, the court prevented Georgia from punishing as fully as it wanted one Black activist who’d had the audacity to radically challenge the class and racial status quo. By the time of that intervention, however, Herndon had already been severely punished. The intervention, moreover, did not subsequently prevent Georgia or the United States from prosecuting other dissidents on ideological grounds.

Despite judicial precedent, the specter of repression survives as an omnipresent threat to civil liberties today. Much better than a favorable court ruling is the kind of robust public opinion that precludes prosecutions violative of constitutional rights. By the time the courts get involved in the defense of civil liberties, precious freedoms have already been lost.

Time is running out to have your gift matched

In this time of unrelenting, often unprecedented cruelty and lawlessness, I’m grateful for Nation readers like you.

So many of you have taken to the streets, organized in your neighborhood and with your union, and showed up at the ballot box to vote for progressive candidates. You’re proving that it is possible—to paraphrase the legendary Patti Smith—to redeem the work of the fools running our government.

And as we head into 2026, I promise that The Nation will fight like never before for justice, humanity, and dignity in these United States.

At a time when most news organizations are either cutting budgets or cozying up to Trump by bringing in right-wing propagandists, The Nation’s writers, editors, copy editors, fact-checkers, and illustrators confront head-on the administration’s deadly abuses of power, blatant corruption, and deconstruction of both government and civil society.

We couldn’t do this crucial work without you.

Through the end of the year, a generous donor is matching all donations to The Nation’s independent journalism up to $75,000. But the end of the year is now only days away.

Time is running out to have your gift doubled. Don’t wait—donate now to ensure that our newsroom has the full $150,000 to start the new year.

Another world really is possible. Together, we can and will win it!

Love and Solidarity,

John Nichols

Executive Editor, The Nation

More from The Nation

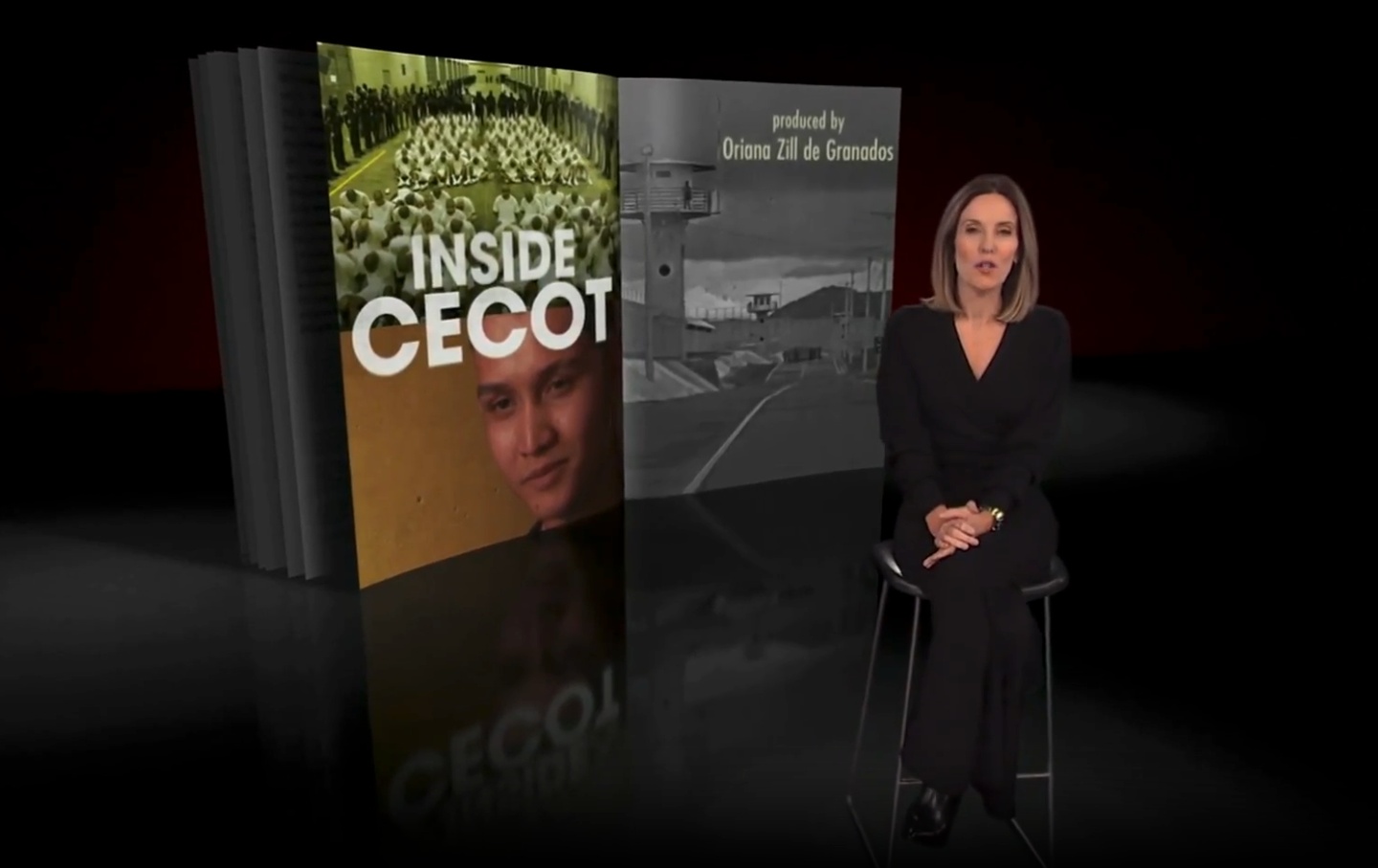

Read the CBS Report Bari Weiss Doesn’t Want You to See Read the CBS Report Bari Weiss Doesn’t Want You to See

A transcript of the 60 Minutes segment on CECOT, the notorious prison in El Salvador.

The Christmas Narrative Is About Charity and Love, Not Greed and Self-Dealing The Christmas Narrative Is About Charity and Love, Not Greed and Self-Dealing

John Fugelsang and Pope Leo XIV remind us that Christian nationalism and capitalism get in the way of the message of the season.

In Memoriam: Beautiful Writers, Influential Editors, Committed Activists In Memoriam: Beautiful Writers, Influential Editors, Committed Activists

A tribute to Nation family we lost this year—from Jules Feiffer to Joshua Clover, Elizabeth Pochoda, Bill Moyers, and Peter and Cora Weiss

Trump’s Anti-DEI Crusade Is Going to Hit White Men, Too Trump’s Anti-DEI Crusade Is Going to Hit White Men, Too

Under the Trump administration’s anti-DEI directives, colleges would be forced to abandon gender balancing, disadvantaging men.

Why We Need Kin: A Conversation With Sophie Lucido Johnson Why We Need Kin: A Conversation With Sophie Lucido Johnson

The author and cartoonist explains why we should dismantle the nuclear family and build something bigger.

Bari Weiss’s Counter-Journalistic Crusade Targets “60 Minutes” Bari Weiss’s Counter-Journalistic Crusade Targets “60 Minutes”

The new editor in chief at CBS News has shown she’s not merely stupendously unqualified—she’s ideologically opposed to the practice of good journalism.