The Most Public Intellectual

Walter Lippmann’s 20th century.

Walter Lippmann’s Phantom Publics

Arguably no American journalist wielded as much influence as Walter Lippmann did in the 20th century. But what did he do with that power?

Writing in The New Republic, the magazine Walter Lippmann helped to create, Alfred Kazin observed: “Lippmann was one of the most successful people who ever lived…. No other journalist in American history has had so much influence on events, had his hand in so many state papers, been on such equal terms with the great. No other wrote books that became such famous keys to each era in turn, was able to impart to newspaper and magazine columns, with such a magisterial air of cultivation, political intelligence of the coolest and most decisive sort.”

Books in review

Walter Lippmann: An Intellectual Biography

Buy this bookThe striking thing about this effusion is that Kazin, hardly the most generous and usually the most competitive of souls, meant it. Also, it is literally true. Proof of concept is Ronald Steel’s 1980 masterpiece, Walter Lippmann and the American Century, which prompted Kazin’s observations and is still, for my money (apologies, Robert Caro), the best and most engrossing American political biography ever written. In it, we are introduced to a brilliant and influential political journalist who, in a half-dozen different ways and arguably more, shaped the “American Century” with his bottomless energies, his powerful intellect, his gift for clear, incisive writing, and his instinctive comfort (for good and ill) in the precincts of power.

Lippmann was a unique figure in American letters, someone who towers over almost every political columnist who has plied the trade since World War I. He also towers over almost all of his peers in political philosophy, with the possible exception of John Dewey. Lippmann was the public intellectual of the 20th century: Few burnished their brainy brand of opinion-slinging in print and, occasionally, broadcast media more prolifically and seriously, or with such a depth and breadth and elegance (despite a propensity for memorable mistakes, which we’ll get to) in the public square, than he did.

Tom Arnold-Forster, a historian at Oxford University, has now scrutinized Lippmann’s life, his journalism and political thought, and his anxieties about the liberal order he helped establish, in a new intellectual biography that serves as an academic counterpart to Steel’s. Arnold-Forster has, as the saying goes, turned every page of every column, book (published text and early drafts), and surviving letter that Lippmann ever wrote. He has also summited the mountain of writing to and about him and thought hard about it all, giving us a portrait of the philosophical Lippmann in full depth and granular detail. At times, it must be said, the author’s self-proclaimed method of “ruthless historicization” can mire the reader in the weeds of Lippmann’s shifting pronouncements (pronouncing being his preferred rhetorical mode) at the expense of the broader view, and the book lacks the narrative élan of Steel’s. Yet in its rigorous fashion, it also offers a hard-to-top history of not just the man but also the liberalism that he was the most visible figurehead of over the decades.

Walter Lippmann was born on the Upper East Side of Manhattan in 1889 to a prosperous German Jewish family, though he generally regarded his Jewish identity as an irrelevance or an inconvenience. A scholastic prodigy, Lippmann went on to Harvard, where as a member of the brilliant class of 1910 (which included John Reed and T.S. Eliot) he thrived, attracting the attention of such mentors as George Santayana, William James, and even Theodore Roosevelt. Reed would introduce Lippmann, tongue not entirely in cheek, as the future president of the United States. He was, as was the fashion in those days, a socialist until graduation and slightly after, working for a bit as a secretary for the socialist mayor of Schenectady, New York, until politics as praxis paled, and then as a researcher for the famed muckraking journalist Lincoln Steffens.

More than any other profession, journalism was Lippmann’s natural destination. He was recruited by Herbert Croly, author of the influential “New Nationalism” treatise The Promise of American Life, to be one of the founding editors of The New Republic. It was the making of Lippmann, as he was the making of it. His skillful writing and editing and his keen sense for the new possibilities and necessities in American politics were crucial to making this low-circulation, high-influence journal of ideas the standard-bearer for a new liberalism that emerged from an older Progressivism.

Few magazines have punched more spectacularly above their weight than The New Republic in terms of political influence. It became an intellectual laboratory for the Progressivism of President Woodrow Wilson’s administration, and Lippmann its in-house philosopher. This brought him into contact with the highest circles of power, and when the United States entered the First World War, he crossed over to the government side as a member of something called the Inquiry, a colloquy of grandees tasked with formulating a new geopolitical posture for the country and a set of war aims to impose on the Allies. The result was the famous Fourteen Points (“open covenants of peace, openly arrived at,” among the other resonant phrases Lippmann may have coined). “A liberal manifesto for self-determination and public diplomacy,” in Arnold-Forster’s words, it was received with scarcely concealed scorn by the French and the British for its woolly-minded and politically naïve idealism. As a blueprint for peace in the postwar world, it was dead on arrival.

The experience left Lippmann with a bad taste in his mouth and a singed reputation. Having voiced his unwelcome views to anyone willing to listen, he found himself at odds with Wilson and his wartime circle. Toward the end of the war, Lippmann joined the US Army’s propaganda unit, writing leaflets urging surrender to be dropped behind the German lines. After his discharge, he remained in France to cover the Paris Peace Conference, coming to share the same dismay and disgust at its botched results that John Maynard Keynes gave memorable voice to in The Economic Consequences of the Peace.

After the war, Lippmann returned to The New Republic and published his landmark Public Opinion in 1922. The book was one of the most sustained and influential attempts to square the competing demands of democracy with the complexities of mass society and the requirements for expertise in running it. Social psychology was still in its infancy as a discipline, and Lippmann complained that “political science [is] taught in colleges as if newspapers did not exist.” The problem for a democracy under these new conditions, he wrote, was that “the real environment is altogether too big, too complex, and too fleeting for direct acquaintance.”

Lippmann understood that the vast majority of what used to be called citizens could have only a partial or obscured view of the broader reality, if they even bothered to acquire one. “The pictures in our head,” as he put it, rarely conform to that reality. Repurposing a term from typesetting, he called these pictures “stereotypes” and argued that the mass of people conduct their mental lives in uninformed and often wildly inaccurate “pseudo-environments,” a term prefiguring Daniel Boorstin’s later coinage “pseudo-events.”

Lippmann framed the problem and its possible solution this way: “I argue that representative government, either in what is ordinarily called politics, or in industry, cannot be worked successfully, no matter what the basis of election, unless there is an independent, expert organization for making the unseen facts intelligible to those who have to make the decisions.” Democratic politics, he insisted, was at odds with informed and effective governance. To remedy this situation, he floated the vague idea of entities he called “intelligence bureaus” that would be tasked with guiding the policymakers in Washington on the right path. You could argue that the modern, government-funded (at least for now) universities and the many advisory and regulatory agencies that exist (at least for now) have over time realized Lippmann’s fuzzy vision.

After eight years at The New Republic, Lippmann entered a far wider journalistic arena in 1922 when he became an editor and opinion writer for the New York World, a Pulitzer-owned paper seeking to escape its yellow-journalism past. In its pages, Lippmann addressed the problem of public opinion by taking on the task of molding it himself. He became a strong supporter of the Democratic governor of New York, Al Smith, the avatar of so-called urban liberalism in a Republican-dominated decade. In 1931, when the paper was sold, Lippmann moved over to the centrist Republican paper The New York Herald Tribune, where his column “Today and Tomorrow” ran until 1962; syndicated, it appeared in hundreds of papers nationwide with a combined circulation of 10 million. The column was a must-read item in the pinnacles of power and also for those of more middlebrow persuasion seeking guidance on the issues of the day (as James Thurber memorably depicted in a 1943 New Yorker cartoon in which a perturbed wife looks up from her paper to inform her husband, “Lippmann scares me this morning”). He became a one-man intelligence bureau, you might say, molding public opinion as effectively as and for longer than any other American journalist has.

Over the decades of Lippmann’s column for the Trib, he never strayed too far from the political center—a congenial place for its moderate Republican positions and readership. Letters praising the paper for its open-mindedness in allowing such slightly alien but still palatable viewpoints in its pages were printed with regularity. Lippmann helped to reify the Cold War in the public mind by the simple expedient of capitalizing the term in a series of 14 columns on the subject in the late 1940s. (Bernard Baruch and George Orwell had used the phrase earlier in lower case.) But Lippmann was by no means a doctrinaire cold warrior. He took sharp issue with George Kennan’s famous containment policy, preferring to hew to a realpolitik position in regard to which fights to pick and which to concede with the Stalin-led Soviet Union.

Arnold-Forster has left almost no thought of Lippmann’s unturned in amassing this intellectual biography, and a review cannot do real justice to its capaciousness. It is, however, a good deal easier (and a lot more fun) to focus on Lippmann’s mistakes, some of which were real doozies. Probably the most quoted of Lippmann’s sentences is this dismissal of Franklin Roosevelt as a candidate for president in 1932: “He is a pleasant man who, without any important qualifications for the office, would very much like to be president.” Lippmann changed his mind about FDR for a while as the New Deal took shape, but by 1936 he was endorsing Alf Landon, an oilman and the Republican governor of Kansas, for president. But his worst moment as a pundit came in 1933, when he described a speech by Adolf Hitler as “statesmanlike” and representing “the authentic voice of a genuinely civilized people.” He even suggested that the Nazi persecution of Jews was “a kind of lightning rod which protects Europe”; his longtime friend Felix Frankfurter wouldn’t speak to him after this for more than three years.

There were other blunders along the way. Earlier, Lippmann had been fully supportive of Harvard president A. Lawrence Lowell when he sought to impose a quota on Jewish students accepted at the university, inveighing against what Lippmann termed those “vulgar and pretentious Jews” who brought obloquy upon themselves; later he also supported the internment of Japanese Americans during the Second World War.

Lippmann was at odds with Lyndon Johnson over the Vietnam War, which he viewed as a geopolitical disaster, but in 1968—unnerved by the radical and unruly turn its opposition had taken—he endorsed Richard Nixon for president. And he was such a complete snob that he once boasted, “I have not the vaguest idea what Brooklyn is interested in.” (That’s the old salt-of-the-earth Brooklyn of William Bendix and Betty Smith, in case you were confused.)

For a philosopher-king of American liberalism, Lippmann ended up displaying a considerable amount of contradiction and inconsistency. In accounting for these shifts, Arnold-Forster uses a lot of phrases that feel like oxymorons, among them “liberal imperialism” and “a conservative liberal grandee.” Earlier he quotes Herbert Croly’s description of The New Republic, the place where Lippmann made his bones, as “radical without being socialistic.” You could interpret this unkindly, as a descriptor for a thinker whose liberal principles were tropic toward power politics and its perceived necessities. Certainly, no one ever described Lippmann as an idealist.

Early in the book, Arnold-Forster tosses off the term “bathetic” liberalism, one that I’ve spent a lot of time trying to figure out. I think what he means is that the liberalism that Lippmann stood for, supposedly based on democratic principles but apt to bend or discard them as the circumstances dictated, sufficed as an ideology for decades, especially in the “consensus” postwar period, but in the post-Vietnam period had lost its way and become increasingly sad and incoherent. If so, it is hard to disagree with him; the phrase certainly resonates today.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →If I may be permitted to end on a personal note: I spent a lot of time reading around in Lippmann’s columns and books, and I have some thoughts. I find him impressive on a literary and intellectual level and fantastically interesting as an actor in American political history. But as a writer and thinker, he can be arid and uninspiring and short on compassion. One of Arnold-Forster’s idées fixes is to correct the view of the Lippmann-Dewey relationship as an extended elitist/technocratic versus small-d democratic rivalry, since he finds more commonalities than divergences in their political thought. He makes a convincing enough case, but even so, Dewey still gives off far more human warmth, if considerably less intellectual clarity, and is far more persuasive on the core principles and moral imperatives of democracy than Lippmann—a top-down elitist in his bones—ever was.

I’ve looked long and hard at the photo of Lippmann on the cover of Arnold-Forster’s book, head cradled in his hand, casting a sorrowful but detached side-eye on the messy human prospect. He is emphatically not a man you’d care to share a beer with. As a liberal thinker, he represents the limits of cerebral rationalism and the politics of expertise, short on democratic faith and the instincts of the skilled political animals or “happy warriors” that the Democrats used to produce with regularity.

This all hit me with great force when I stumbled across a June 9, 1932, column by Lippmann on the hapless Bonus Marchers, World War I veterans who had descended by the thousands on Washington, DC, to try to collect early on a bonus that Congress had promised them. Lippmann expresses some pro forma sympathy for these men and their economic plight at the start. But then he warms to his real theme, which is that they completely failed to grasp the principles of compound interest in demanding early payment! They were asking for something that Congress had never granted them, you see. Lippmann’s “solution” to the whole vexing problem was to explain all this to the Bonus Marchers firmly, offer help to some of them in returning to their far-flung homes, provide “unattractive relief for those who stay on,” and refuse to admit any other marchers to the Capitol, despite any constitutional right of assembly to the contrary.

Herbert Hoover, of course, found his own solution to the problem by summoning the US Army under Douglas MacArthur to brutally expel the veterans from their makeshift encampment on the Anacostia Flats, which the Army burned down, and force them back across the river to points north and west. In the end, Lippmann supported this atrocious action, calling the Bonus Marchers “a pressure group.”

Some liberal.

More from The Nation

The Truth About Interracial Intimacy The Truth About Interracial Intimacy

In a new memoir, author Dorothy Roberts explores why interracial attraction can’t be disentangled from the larger forces of race, gender, and power that govern our world.

Bad Bunny’s Stunning Redefinition of “America” Bad Bunny’s Stunning Redefinition of “America”

His joyous, internationalist, worker-centered vision was a declaration of war against Trumpism.

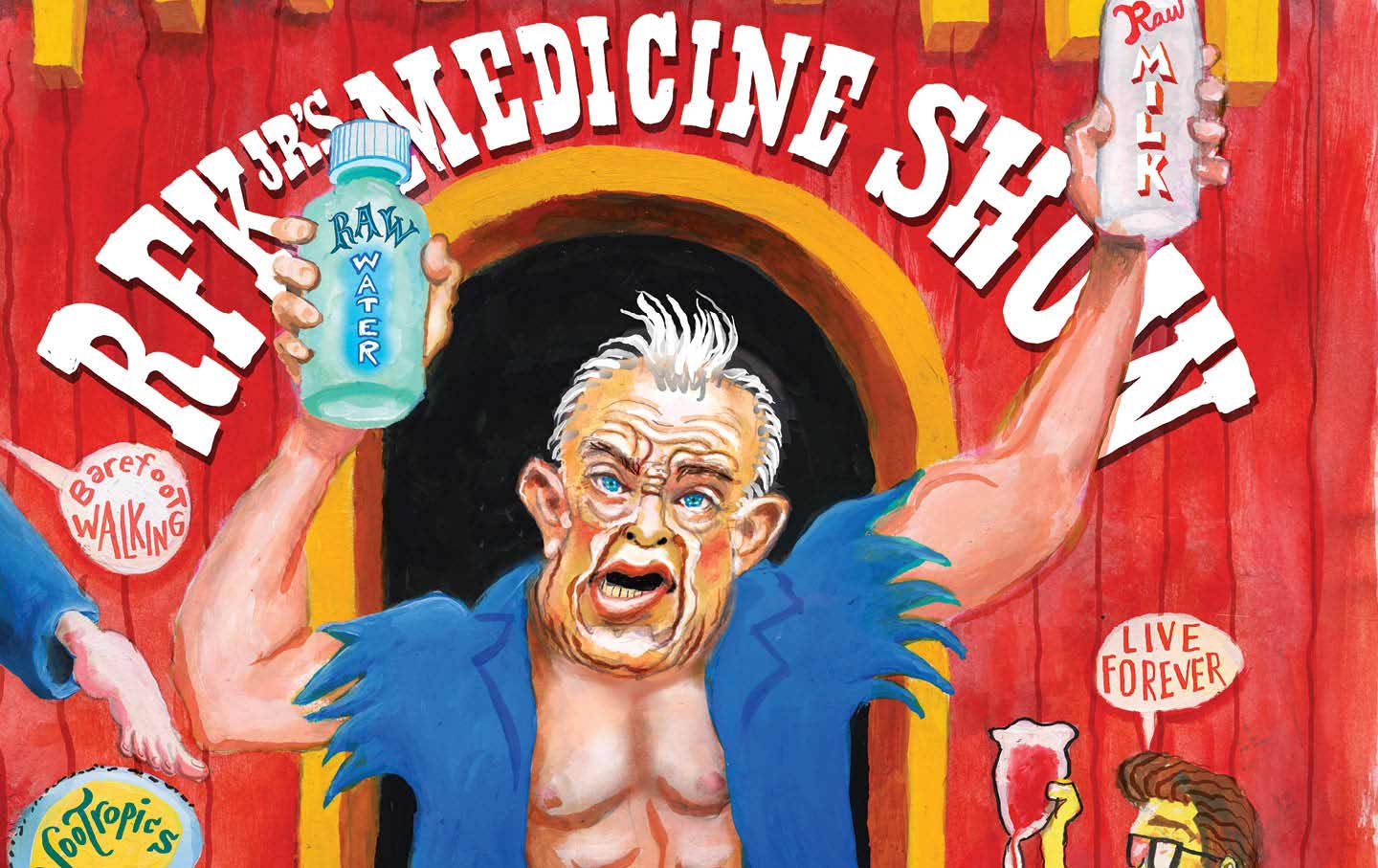

How the Far Right Won the Food Wars How the Far Right Won the Food Wars

RFK’s MAHA spectacle offers an object lesson in how the left cedes fertile political territory.

What the Pro-Choice Movement Can Learn From Those Who Overturned “Roe” What the Pro-Choice Movement Can Learn From Those Who Overturned “Roe”

The anti-abortion movement was methodical and radical at the same time. The abortion-rights movement must be too.

“Shut Up and Serve”: The Professional Tennis Players Fighting a Rigged System “Shut Up and Serve”: The Professional Tennis Players Fighting a Rigged System

An antitrust lawsuit calls the professional tennis governing bodies “cartels” that exploit players and create an intentional lack of competitive alternatives. Can players hit back...

The Real Harm of Deepfakes The Real Harm of Deepfakes

AI porn is what happens when technology liberates misogyny from social constraints.