These Journalists Saw Israel Kill Their Colleagues. But They Refuse to Be Silenced.

The strike that killed Anas al-Sharif nearly claimed the lives of these other reporters—including al-Sharif’s cousin.

Mourners carry the body of the journalists slain in an Israeli air strike the day before, on August 11, 2025, in Gaza City.

(Yousef Al Zanoon / Anadolu via Getty Images)On August 10, 2025, an Israeli missile struck what was meant to be a space of safety—a media tent for Al Jazeera journalists outside Al-Shifa Hospital in Gaza City.

The attack killed six journalists and photojournalists, almost all of whom had been working for Al Jazeera. They were: Anas al-Sharif, 28; Mohammed Qreiqa, 33; Ibrahim Zaher, 25; Mohammed Nofal, 29; Moamen Aliwa, 23; and Mohammed al-Khalidi, 37.

With over 240 journalists killed since October 2023, this ongoing genocide has become the deadliest ever for the press. But behind those numbers are people—people who have left behind family, friends, and colleagues. Three of those colleagues are Ayman al-Hassi, Mohammed Qita, and Mohammed al-Sharif, who is Anas Al-Sharif’s cousin. They narrowly avoided being killed themselves in the August 10 attack.

For them, the blast shattered the fragile boundary between grief and duty. Their stories speak to the unbearable decisions they’re forced to make: rush to aid fallen friends or stay behind the lens; break down; or press on.

I spoke to al-Hassi, Qita, and Mohammed al-Sharif about their horrific experiences of the attack and how they are coping in its aftermath.

“Between Saving and Witnessing”

“Ifound myself facing two impossible choices: rescue my colleagues or document what was happening. I chose documentation, because civilians and medics were already trying to save them, but if we did not film, the world would not know.”

These are the words of Ayman al-Hessi, 32, a photojournalist who narrowly avoided death that night. Just half an hour before the missile struck, he had gone home to play with his daughter.

As he drove back toward al-Shifa, the sound of an explosion froze him. His phone rang: colleagues told him that the journalists’ tent had been struck. He sped toward the hospital, crashing his car into a wall in panic, before reaching and seeing the scene.

He recalls: “The tent was still burning. I saw the martyrs laid out on the ground. Moamen Aliwa was slumped killed on a chair. Beside him, Ahmad al-Harazin, the logistical man, was gravely injured. Then I saw Anas, Mohammed Qreiqa, Ibrahim Zaher, and Mohammed Nofal lying motionless. The wall behind the tent was full of shrapnel. It was the most devastating strike I had ever seen.”

For 45 minutes, al-Hessi filmed the aftermath: the wounded carried out, the martyrs wrapped, the cries of relatives who arrived at al-Shifa’s overcrowded gates. “At one point, I broke down. I sat in a corner, sobbed, and cried intensely. But then I returned to my camera since there is no choice for me unless I document the Israeli crimes against my people in Gaza,” he says.

His decision reflects the impossible dilemma Gaza’s journalists face. “We do not love danger or seek death,” al-Hessi explains. “We are human beings with families and dreams. But we cannot abandon our people. If we do not show the truth, no one will.”

“The Night Truth Was Burned”

Mohammed Qita, 30, a freelance journalist, was in a nearby tent when the missile hit. Seeking a better internet connection, he had just stepped outside when the explosion ripped through the air.

“Suddenly, everything collapsed into fire and screams. I heard my colleague Mohammed al-Khaldi shouting at me to escape from the back door. Minutes later, he passed away due to his injuries,” Mohammed says. “My instinct told me to run, but my heart pulled me back. I realized Anas was inside.”

Qita’s powerful video records his cries of “Anas! Anas!” as he staggers back into the blazing fire. The first body he saw was that of Mohammed Qreiqa, burning: “I tried to put out the flames with my bare hands. I knew he was gone, but I couldn’t let him die twice.”

Then came the unbearable sight of al-Sharif, whose body was thrown outside the tent by the explosion’s impact: “I collapsed. I could not process it. Then I saw Moamen, killed on his chair, and Mohammed Nofal, his body without a head.”

In his attempts to save colleagues, Qita suffered burns to his hands and shrapnel wounds in his back, one nearly paralyzing him. But his deepest scars are not physical. “The real injury,” he says, “is the helplessness of seeing your friends burn while you are powerless. That extinguishes your soul.”

Even so, Qita insists on returning to work: “The camera is no longer a tool. It is a will left by my friends. We cannot let their voices die.”

“An Attack on the Witness”

Mohammad Al-Sharif, 29, a correspondent for Al Jazeera Mubasher and a cousin of Anas Al-Sharif, was at the site minutes after the missile fell. “The scene was unspeakable, colleagues lying on the ground, killed. I felt grief deeper than words can express. But I also felt the weight of responsibility: if we stop, Gaza will lose its voice,” he says.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Anas and Mohammed were born in the same year in Jabalia in the north of Gaza, grew up together, and entered journalism side by side. “Anas was not only my cousin; he was my brother,” he says. “He was courageous, even after surviving multiple assassination attempts and after his father was killed in a strike on their home in Jabalia on December 11, 2023. He kept reporting, even under daily threats from the Israeli army. His last stories on the famine in Gaza moved the world; they forced aid trucks in. That was his victory.”

Mohammed described his cousin as “the voice of Gaza.” His coverage of a starving woman collapsing in the street, tears streaming down his face as he narrated, was a moment of raw humanity that pushed global outrage. “He showed that journalism is not just about recording, but it is about feeling, about carrying people’s pain,” Mohammed says.

These martyred journalists had dreams, families, and loved ones who now live with the pain of their absence. Anas left behind his children, Sham and Salah, his wife, Bayan, and his mother. Qreiqa followed his mother, who was executed by the occupation forces during a raid on Al-Shifa Hospital in March 2024, leaving behind his wife Hala and their children, Zein, Zeina, and Sanad. Mohammed Nofal left behind six sisters, his brother Ibrahim—a cameraman for Al Jazeera English—and his father, Riyad Nofal. He is now reunited with his brother Omar, who was killed at the beginning of this genocidal war, and his mother, who was martyred in June 2025.

Likewise, Khalidi, Aliwa, and Ibrahim Zaher left behind parents whose hearts now carry the weight of loss and longing, entrusting their sons with the memory of fathers who once told the truth with their cameras and words.

The stories of Ayman al-Hessi, Mohammed Qita, and Mohammad al-Sharif reflect the heart and resilience of the Gaza journalists who are still alive.

Each time they raise their cameras, they’re not only capturing moments but honoring voices that were silenced too soon. They keep going, because if they don’t, who will speak for Gaza?

Or, as Anas al-Sharif said so often: “The coverage continues.”

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

Brace Yourselves for Trump’s New Monroe Doctrine Brace Yourselves for Trump’s New Monroe Doctrine

Trump's latest exploits in Latin America are just the latest expression of a bloody ideological project to entrench US power and protect the profits of Western multinationals.

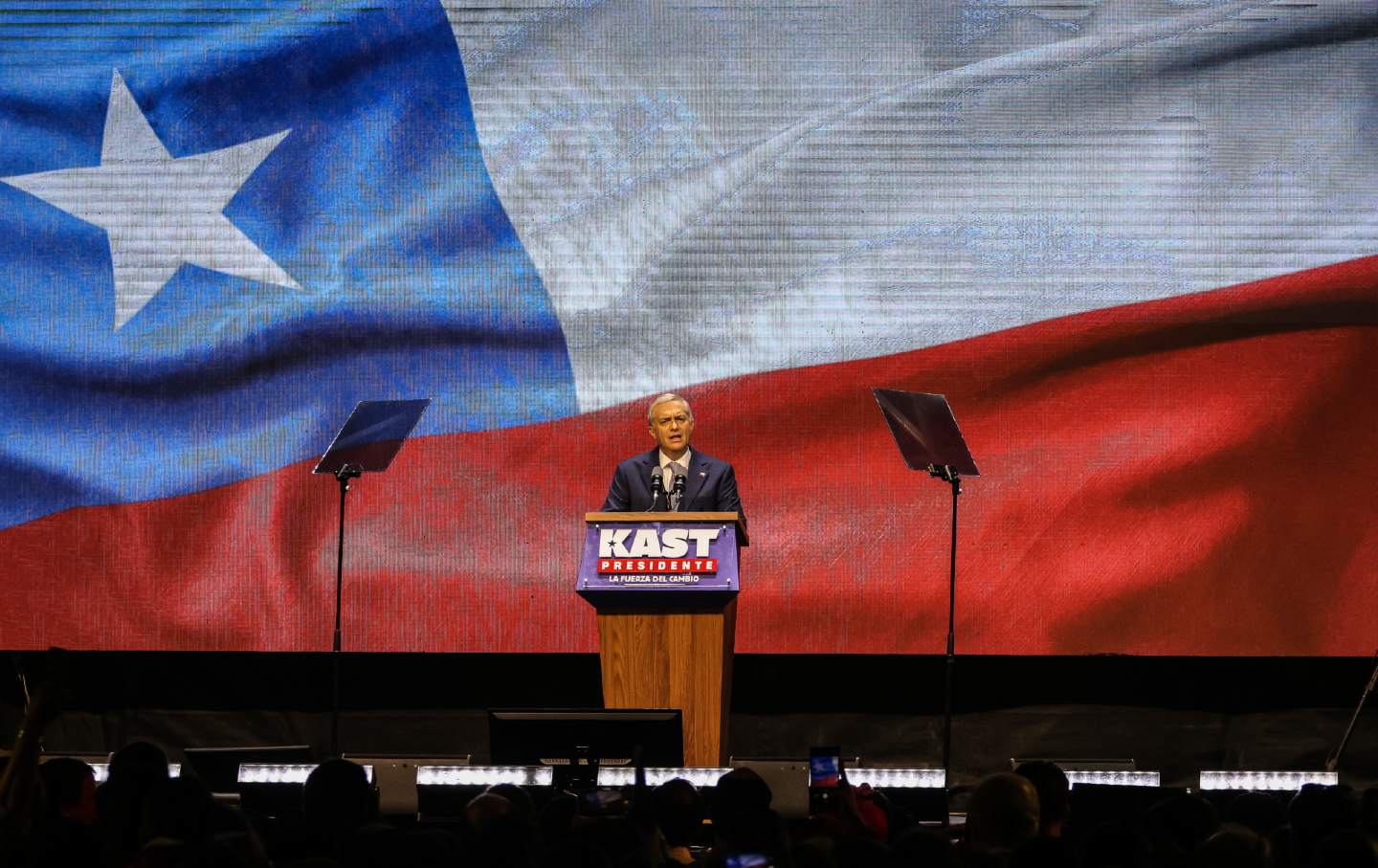

Chile at the Crossroads Chile at the Crossroads

A dramatic shift to the extreme right threatens the future—and past—for human rights and accountability.

The New Europeans, Trump-Style The New Europeans, Trump-Style

Donald Trump is sowing division in the European Union, even as he calls on it to spend more on defense.

The United States’ Hidden History of Regime Change—Revisited The United States’ Hidden History of Regime Change—Revisited

The truculent trio—Trump, Hegseth, and Rubio—do Venezuela.

Mahmood Mamdani’s Uganda Mahmood Mamdani’s Uganda

In his new book Slow Poison, the accomplished anthropologist revisits the Idi Amin and Yoweri Museveni years.

The US Is Looking More Like Putin’s Russia Every Day The US Is Looking More Like Putin’s Russia Every Day

We may already be on a superhighway to the sort of class- and race-stratified autocracy that it took Russia so many years to become after the Soviet Union collapsed.