What Caused Democrats’ No-Show Problem in 2024?

New data sheds light on the policy preferences of nonvoting Democrats in the last election. It may disappoint some progressives.

Democrats are still trying to figure out what went wrong in the 2024 election. Did the party swing too far to the left or not far enough? Was the Democrats’ defeat due to a failure to turnout base voters or a failure to persuade swing voters?

Answers to these questions typically fall on factional lines. Center-Left analysts, like Nate Cohn or David Shor, favor the “persuasion” theory. They have long argued that Democrats failed because of the party’s inability to convince non-Democrats to vote for them, chiefly because their messaging and political positions were too progressive. Moderation or placing a greater emphasis on bread-and-butter economic issues is their suggested medicine.

On the other side, progressives like The Nation’s Waleed Shahid and Kali Holloway have argued that Trump’s victory is owed to Democratic voter malaise. Because the party didn’t give their base anything to be excited about, Democrats stayed home. As Holloway concluded, “The people who really decided the 2024 election are the ones who didn’t vote at all.” These commentators’ preferred solution is to energize the base with more progressive appeals.

So who’s right? It’s complicated. But new data from the Cooperative Election Study (CES) can get us closer to an answer. The CES is a high-quality survey with a sample-size large enough (60,000 respondents) to permit fine-grained comparisons between subgroups in the US adult population. With it, we’re able to get a clearer picture of who voted and how they felt about the issues.

To begin, it seems likely that the plurality of nonvoters in the 2024 presidential election were indeed Democrats, as the political scientist Jake Grumbach and his coauthors have recently shown. Here is a point for the progressives.

But while “energize the base” advocates are right that more Democrats stayed home than Republicans, they assume that these nonvoters abstained because Democrats didn’t run a sufficiently progressive campaign. To get a sense of whether Democrats who sat out the 2024 presidential election might have been moved to participate if the party had offered a more left-wing policy agenda, we can compare the policy preferences and demographics of voting and nonvoting self-identified Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents.

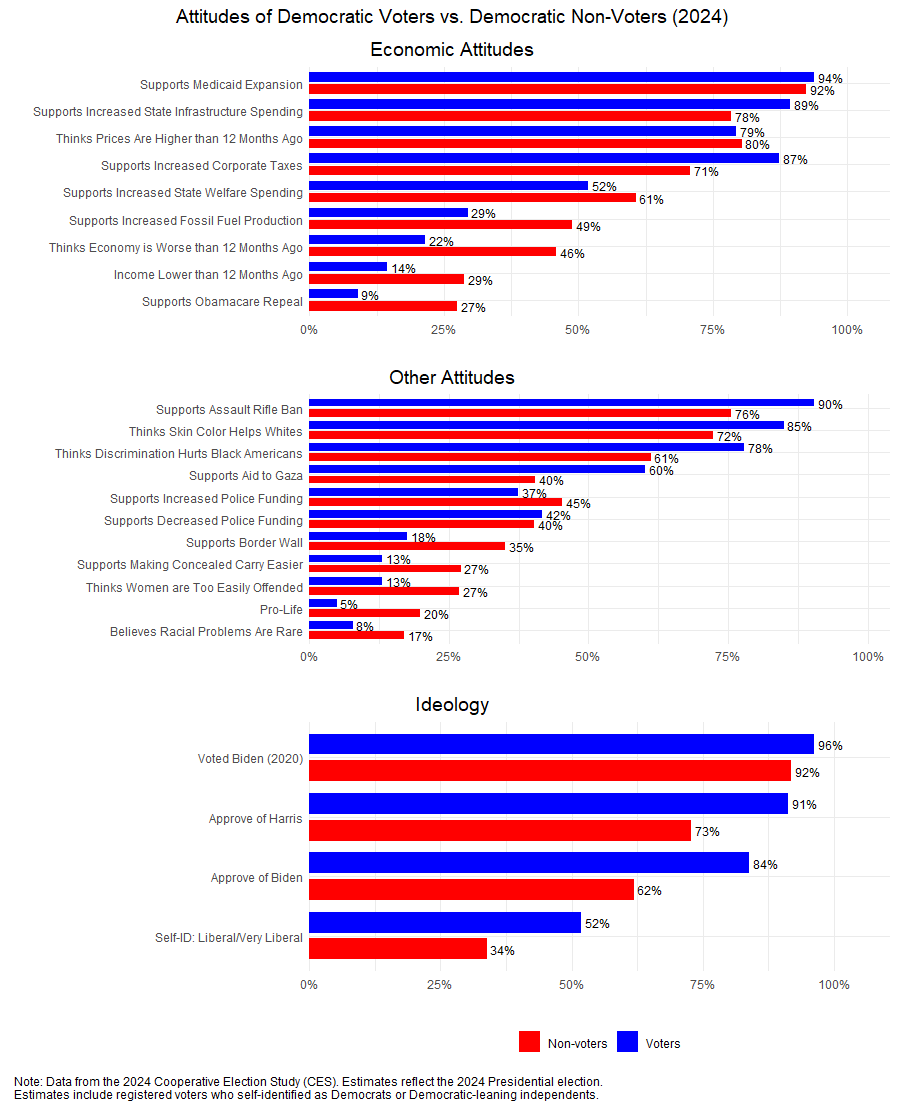

Contrary to what left-wing optimists had hoped, Democratic nonvoters in 2024 appear to have been less progressive than Democrats who voted. For instance, Democratic nonvoters were 14 points less likely to support banning assault rifles, 20 points less likely to support sending aid to Gaza, 17 points less likely to report believing that slavery and discrimination make it hard for Black Americans, 17 points more likely to support building a border wall with Mexico, 20 points more likely to support the expansion of fossil fuel production, and, sadly for economic populists, 16 points less likely to support corporate tax hikes (though this group still favored corporate tax hikes by a three to one margin). Overall, nonvoting Democrats were 18 points less likely to self-identify as “liberal” or “very liberal.” Here is a point for the centrists.

But wait, does all this mean that nonvoting Democrats stayed home in 2024 because Democrats’ policies were too progressive? Not necessarily; while the CES data gives us the ability to judge issue preferences, we can’t use it to determine issue salience. That is, we don’t know which issues were most important to voters nor even if candidates’ issue positions were important factors in nonvoters’ decision to sit out the election.

We should also be careful not to extrapolate too much about the implications of these results for whether Democrats should or should not have moderated their policy positions in different areas, since nonvoting Democrats overwhelmingly supported a range of views typically associated with progressives—such as support for banning assault rifles, believing that skin color gives whites an advantage, support for Medicaid expansion and infrastructure spending, and support for corporate tax hikes.

What we can say based on the CES data, however, is that it appears unlikely that the average nonvoting Democrat would have decided to vote if Democrats had prioritized more progressive-issue positions on the campaign trail.

But can we draw any conclusions about what might have energized nonvoting Democrats?

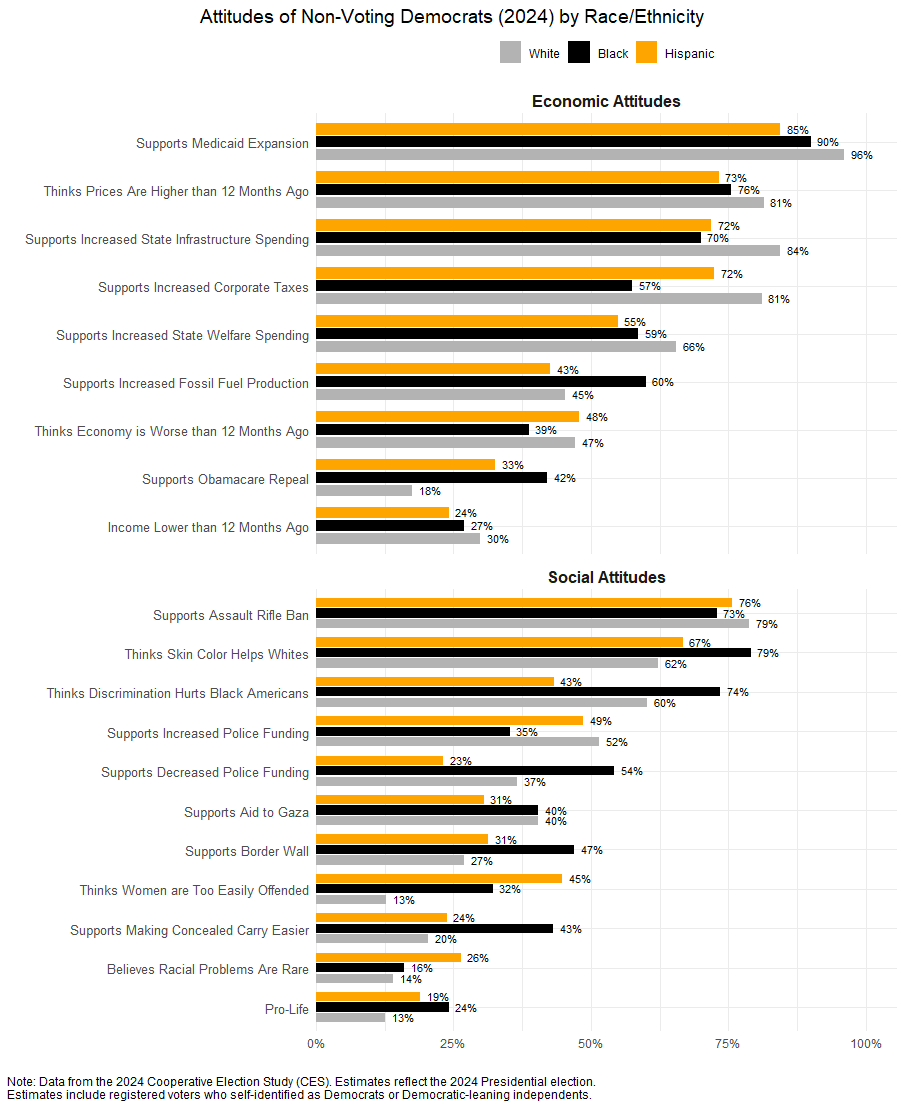

Based on the CES data, two things jump out: First, they were more likely to be non-white. Only 39 percent of Democratic nonvoters identified as white, while 28 percent identified as Black, and 20 percent as Latino. This means that, compositionally, the more conservative profile of nonvoting Democrats (compared to voting Democrats) cannot be attributed to a whiter electorate. This again cuts against progressive claims that non-white Democrats are especially moved by more liberal appeals.

We compared the attitudes of nonvoting white Democrats to those of nonvoting Black and Latino Democrats.These results should be taken with caution. Because the number of nonvoting Black and Latino Democrats is relatively small, there’s a lot of uncertainty around the estimates. That said, some of the gaps between groups are large and consistent enough to suggest real differences in how nonvoting white, Black, and Latino Democrats think about key economic and social issues.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →One of the clearest divides between groups shows up on questions about race, inequality, and policing. While most nonvoters regardless of race or ethnicity agreed that racism remains a problem, Black nonvoters were much more likely than others to see it as a serious barrier to opportunity. These differences also show up in views on policing: White and Latino nonvoters were considerably more supportive of increasing police funding than Black nonvoters (and less supportive of decreasing police spending).

Another consistent pattern is that Black and Latino nonvoters tend to be more socially conservative than white nonvoters across a range of issues. They were more likely to agree with statements like “women are too easily offended” and more supportive of restrictions on abortion (though relatively few Democratic nonvoters of any racial/ethnicity group fell into this category). This conservatism also shows up in views on guns and immigration. Black nonvoters were the most supportive of making it easier to carry concealed weapons and were also the most likely to support building a border wall.

These divides shouldn’t be overstated. But, at the very least, we can say that there is little evidence that nonvoting Black or Latino Democrats are consistently more socially liberal than nonvoting white Democrats. Further, these figures suggest that any attempt to mobilize nonvoting Democrats must grapple with the ideological heterogeneity within their base. Messaging and outreach efforts that fail to navigate these tensions will struggle to bring the party’s most disengaged constituents into the electorate.

The second thing to notice about the demographics of Democratic nonvoters: They were overwhelmingly working class and relatively economically precarious. Democratic nonvoters were nearly twice as likely (60 percent vs. 32 percent) to have a household income of less than $50,000 per year, they were nearly three times less likely to hold a four-year college degree (47 percent vs. 17 percent), twice as likely to be gig workers (31 percent vs. 15 percent), and only half as likely to be union members (27 percent vs. 14 percent). Further, nonvoting Democrats were more than twice as likely as voting Democrats to report feeling the economy is worse now than a year ago (46 percent vs. 22 percent) or that their incomes had recently decreased. And, perhaps not surprisingly given their economic precarity, Democratic nonvoters were substantially more likely than voters to support increased state welfare spending (61 percent vs. 52 percent). These class characteristics show nonvoting Democrats’ economic attitudes in a clearer light. In fact, if Democrats could have done anything to reach more of their base in 2024, then, it seems most likely that they could’ve done so by offering a compelling economic narrative about how they were going to improve the well-being of working Americans.

It’s true that Democrats need to energize their base voters, but our analysis suggests that they’re unlikely to do so successfully through a strategy of blanket progressive appeals to an ideologically diverse base. Instead, Democrats need to persuade nonvoters with a clear and credible message about how the party plans to improve the economic lives of working people. Nonvoting Democrats in 2024 were disproportionately low-income, less educated, and more likely to report financial anxiety. Many of them expressed strong support for progressive economic policies like raising corporate taxes, expanding Medicaid, and increasing public investment in infrastructure. These results are consistent with a range of other survey evidence that has shown that working-class Americans—who make up the vast majority of Democratic nonvoters—are solidly in favor of a wide range of progressive economic policies, including some that fall well to the left of mainstream of Democrats’ economic policy proposals such as creating a federal jobs guarantee and putting workers on corporate boards of directors.

In short, while there is no one-size-fits-all message that would have brought all nonvoting Democrats to the polls, there is strong evidence that a focus on economic appeals is the most promising path forward. That doesn’t mean Democrats should ignore social issues or abandon their core values. But it does mean that to win back the disengaged, the party must do more to convince working-class Americans—across all races and ethnicities—that it will make their lives better.

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation