50 Years After “the Other 9/11”: Remembering the Chilean Coup

Some personal reflections on history, memory, and the survival of democracies.

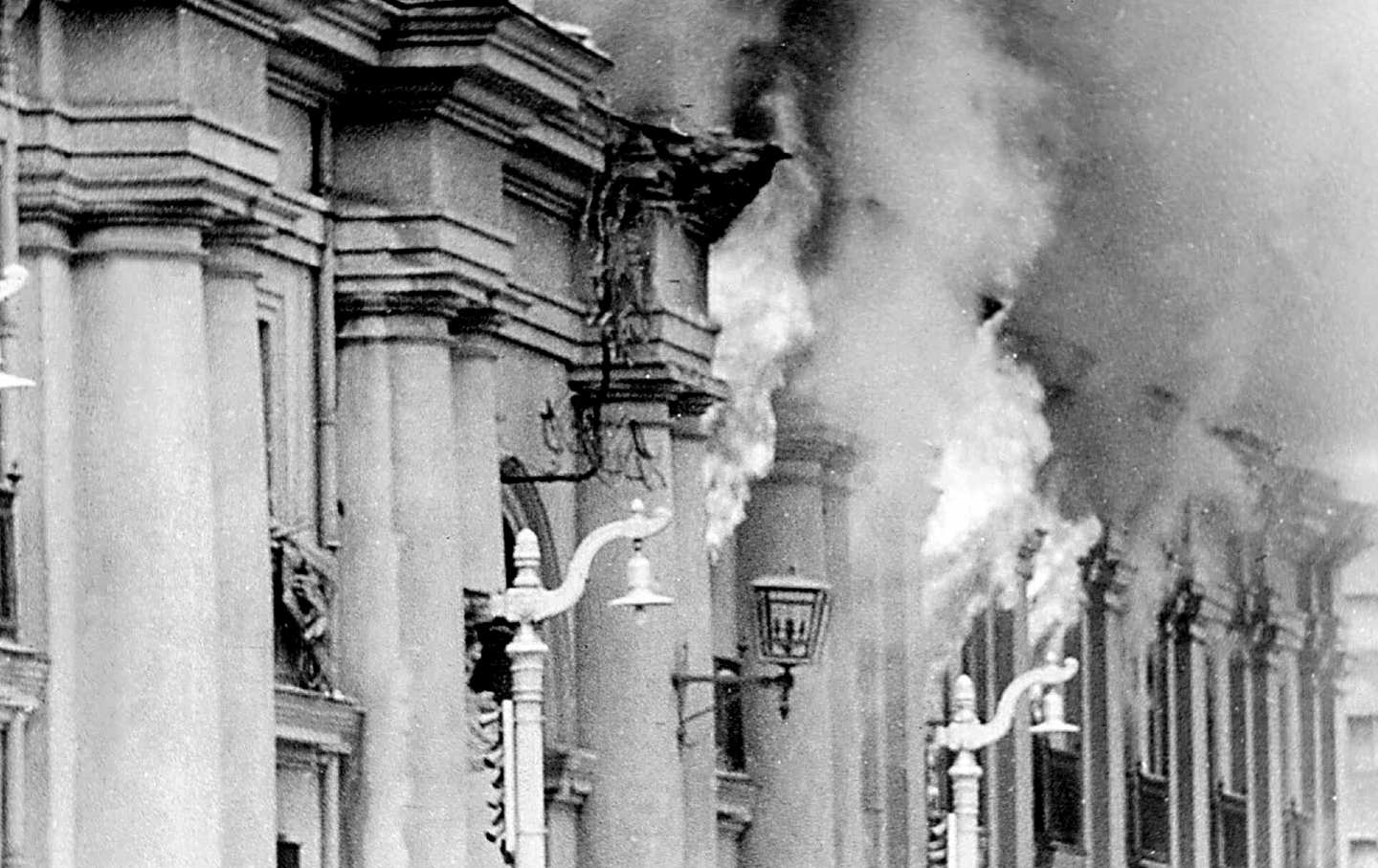

At precisely 13:50 on September 11, 1973, Gen. Javier Palacios sent a succinct message of six words from the Presidential Palace of La Moneda in Santiago de Chile to his superiors in the Armed Forces who had, that very morning, launched a coup d’état against the democratically elected government of President Salvador Allende.

Misión cumplida. Moneda tomada. Presidente muerto.

“Mission accomplished. La Moneda has been secured. The president is dead.”

Palacios—in charge of the troops assaulting the building where Allende and a small contingent of his staff and bodyguards had resisted the demands for his resignation—was signaling the end of one of the most fascinating social and political experiments of the 20th century: the attempt by Allende and his Unidad Popular coalition of left-wing parties to build socialism without resorting to violence.

The violence that Allende had tried to avoid was visited ferociously on the building where he had taken his last stand in defense of dignity and democracy. And if the military had dared to bomb La Moneda from the air and set it ablaze with tanks from the ground, what would they not do to the Chileans (I was one of them) who were fervent followers of Allende? His many supporters—and their vulnerable bodies—soon found out.

In a country where, just the day before, we had enjoyed unrestricted freedom of assembly and expression and could boast about our long-functioning parliament, independent judiciary, and a military that did not intervene in politics, we found ourselves ruthlessly hunted down. I was lucky enough, like thousands of my compatriots, to find my way into exile, dragging along my wife and young child, but innumerable others suffered massive waves of detention, torture, execution—and even more were thrown out of their jobs and blackballed for life. The cruelest torment befell men and women who, kidnapped by security agents, became “desaparecidos,” never to be seen or heard of again.

I am still haunted today by these violations, those broken and twisted and unfinished lives. I cannot walk the streets of Santiago without constantly being reminded, 50 years later, of the pain perpetrated on the friends I lost and continue to mourn, and of the compañeros whose names and stories I never knew but who marched with me on our common quest for a better land.

That was our sin. To have participated, during the thousand days of Allende’s government, in a process of national liberation and popular empowerment that had recovered for the nation its natural resources, implemented an agrarian reform that gave peasants the land their ancestors had toiled on for centuries, made workers and employees responsible for the factories and banks where they labored, and created a volcanic cultural transformation that brought millions of extremely inexpensive books to penurious readers.

Because Allende’s unique experiment—the first time in history that a revolution did not resort to armed struggle to impose its views or eliminate its adversaries—had captured the world’s imagination, our defeat, and the savage repression that followed it, wielded an outsize influence far beyond the borders of what could be expected from a small, remote country at the far edge of the Southern Hemisphere.

Foremost among these global consequences was how our downfall forced left-wing and progressive forces abroad to rethink their strategy for taking power—particularly in Europe. By early 1974, Enrico Berlinguer, the head of the mighty Italian Communist Party, declared that that the lethal outcome of the Chilean peaceful revolution proved that radical reforms required a vast majority behind them, which meant alliances with the middle classes and their representatives. This analysis was later adopted by the Spanish and French Communist parties, leading to Spain’s transition to democracy after Franco and the socialist François Mitterrand’s tenure as president of France. Others on the left, like the Sandinistas in Nicaragua or the guerrillas in Colombia, reached the opposite conclusion: Only by engaging in protracted armed struggle could real change be guaranteed.

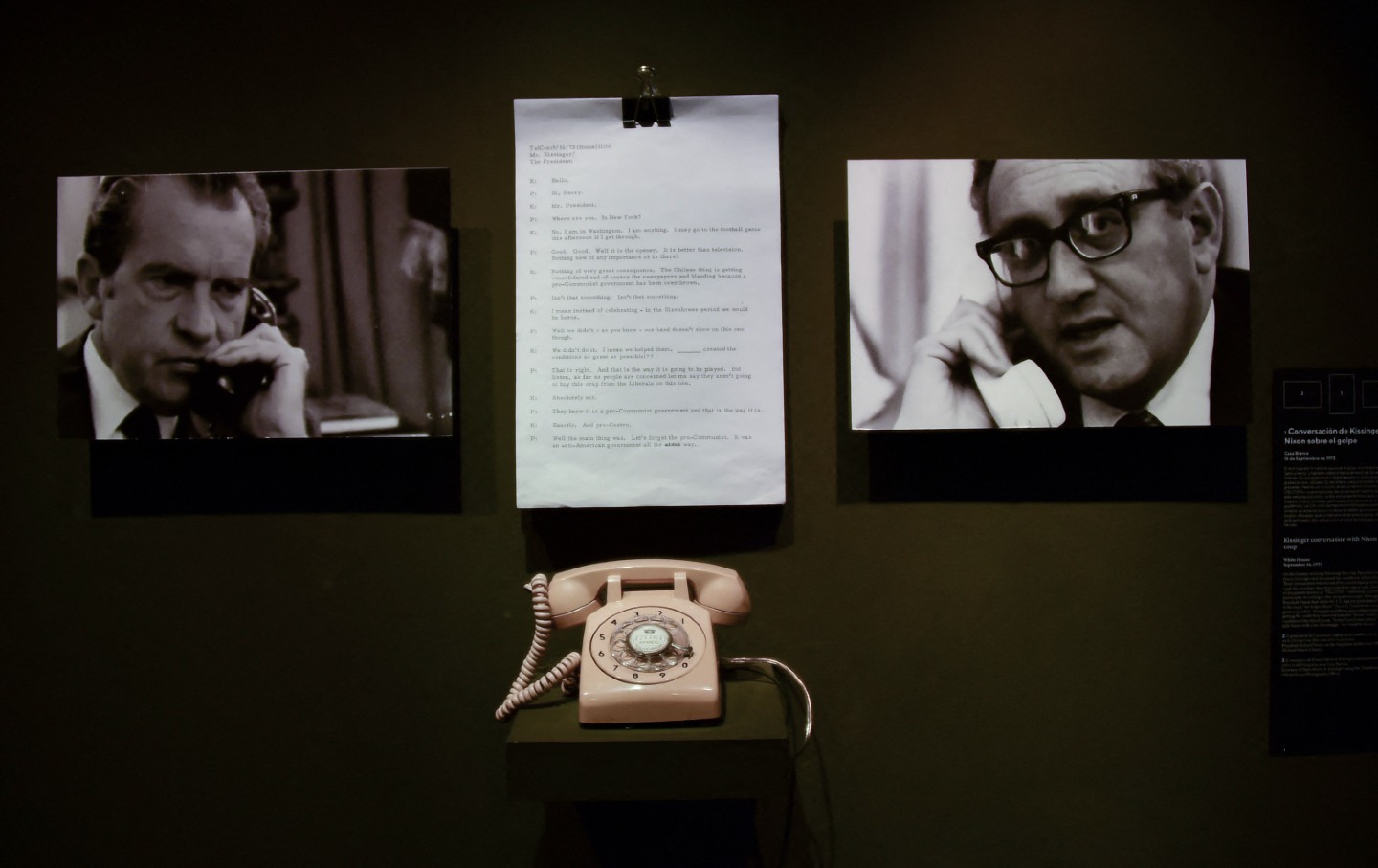

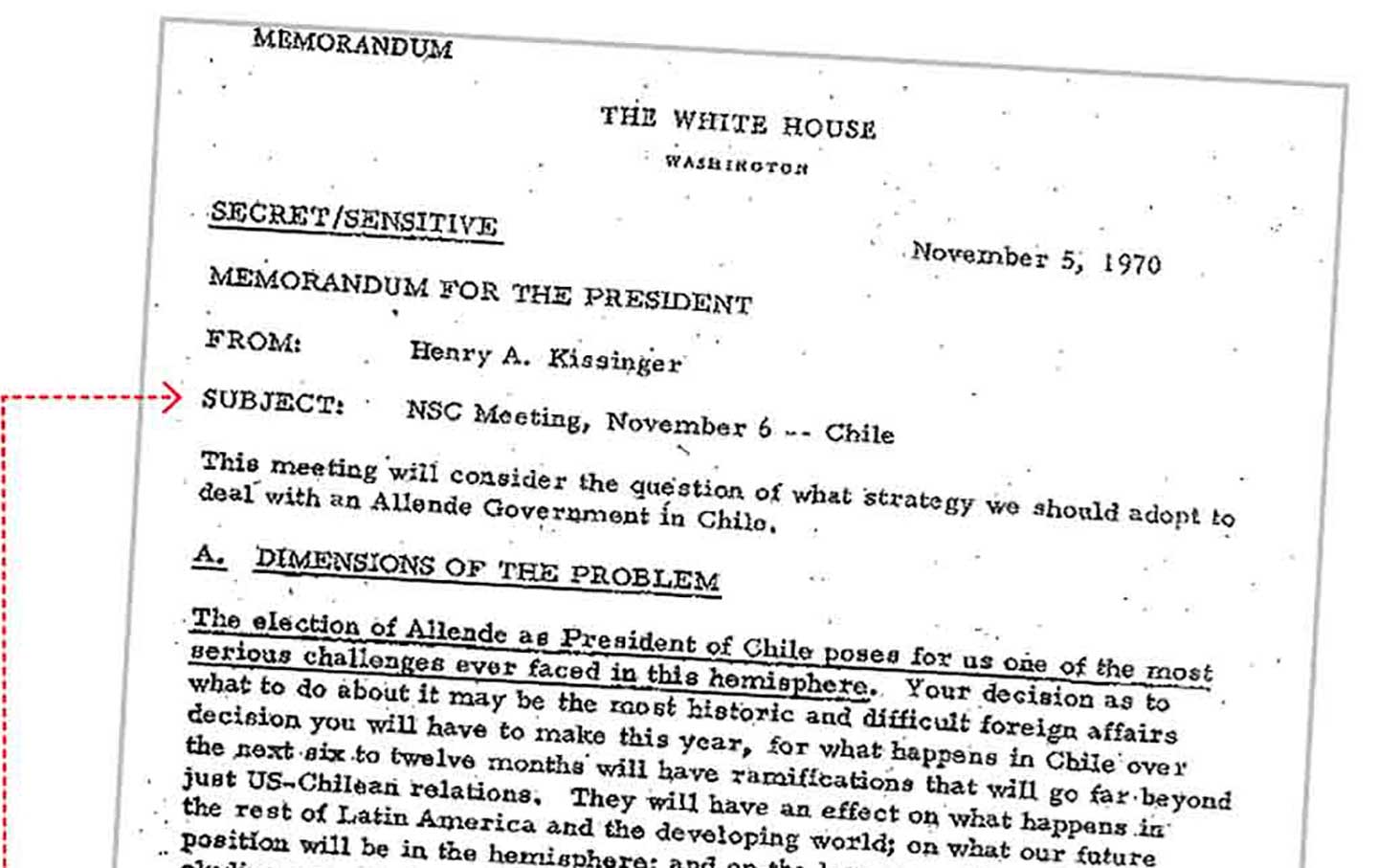

Chile’s coup also had a lasting impact in the United States—not because it shifted revolutionary tactics (there were hardly any revolutionaries) but in how it shaped American foreign policy. Washington had, under Nixon and Kissinger, destabilized the economy of Chile and conspired to overthrow a legitimately elected head of state, fearful that if Allende succeeded, other nations would follow his stirring example of trying to effect radical transformation through the ballot box. A series of amendments in Congress restricted security and military aid to the Pinochet dictatorship. And then came the bombshell investigation by the Church Committee in 1975 that revealed the dirty tactics of the CIA in Chile and led to laws that disallowed aid to governments with appalling human rights abuses. Public consciousness about the atrocities in Chile was a significant factor in making support for human rights—or at least giving lip service to it—one of the cornerstones of American foreign policy.

In other ways, however, the coup and its aftermath exercised a far less benign influence on the United States.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Pinochet’s reign of terror, destined to quash the slightest hint of opposition or criticism, allowed the military—and the right-wing civilians who had instigated the coup and then benefited from the ensuing policies—to turn Chile into a laboratory for neoliberalism: a series of measures that privatized the economy, imposed austerity on an unwilling populace, and trusted an unbridled free market to magically solve all the ills of society. The experiments in Chile were soon exported to other countries like Ronald Reagan’s United States (though Margaret Thatcher came first).

Chile today—33 years after democracy was restored—is still struggling with the legacy of those policies that have inflicted tremendous distress on our citizens. Just one example, among so many: Everywhere I go in my country, I am confronted with disheartening stories of elderly pensioners who cannot make ends meet, left destitute by the dictatorship’s privatization of social security—a situation that, as in constraints in education, health, and Indigenous rights, we still seem powerless to fix.

And yet, to focus only on how the weight of the past presses down on us, limiting our future choices, does not let the whole story of these 50 years emerge.

The way in which Chile’s people finally managed to get rid of our dictator is an inspiration to the world. We defeated Pinochet and the fear he had instilled in every inhabitant of the country in a 1988 referendum that he was supposed to win, given his overwhelming control of the main levers of the economy, the loyalty of dreaded security forces, and the complaisance of the mainstream media. This victory was possible because we Allendistas were able to recognize and criticize our own shortcomings and mistakes—a key step if we were to forge a wide coalition in favor of democracy, joining together with the Christian Democrats who had opposed our president and had welcomed, however reluctantly, the coup. At this time in history when illiberalism is on the rise and so many nations are tempted by authoritarian and demagogic alternatives, Chile is an example of how, with the right political strategy that unifies all in favor of more freedom, courageous and enlightened citizens can refuse to be daunted by the dark forces arrayed against them.

Equally important as a model was our successful transition to democracy in 1990 at a moment when so many countries (socialist ones like those in the Soviet bloc—and right-wing ones like those in South Korea and South Africa) were undergoing similar problems. Also exemplary was how Chile dealt with the crimes committed during the 17 years of despotic rule. Given the lies, denials, and cover-ups during that period, it was crucial to establish what had really happened beyond the shadow of any doubt. For that, a Truth Commission was tasked with this investigation, which resulted in a damning 900-page final report, made all the more stunning by its having been ratified and signed by eminent conservative figures who had supported the previous regime. The commission limited itself to cases ending in death and did not name the perpetrators. But this compromise—necessary in a country where Pinochet retained his position as commander in chief of the army—fostered a national consensus about the need to never again repeat such fratricidal horror. And years later, spurred on by Pinochet’s detention in London in 1998 on charges of crimes against humanity (he escaped a trial by feigning dementia), many of the most egregious human rights offenders in the military and security forces were sentenced to long terms in prison.

Even so, despite these advances, we have not yet healed. The most open wound is undoubtedly the lack of progress in finding the remains of more than a thousand of our compatriots who were disappeared—among them several dear friends whose graves I cannot visit. President Gabriel Boric, a young left-wing admirer of Allende, has made finding those bodies a priority as the country commemorates the 50th anniversary of the coup. He understands that the ongoing tragedy of families unable to mourn exemplifies the way in which the coup is not over for too many in a land of countless victims. During the months I spend every year in Chile, not a day goes by without some outrage from the past saturating me. One morning, it’s a group of rabid neighbors protesting the erection of a memorial in front of the airport from where planes left to cast prisoners into the sea weighed down by railway tracks. The next day, over lunch, an old friend tells me of his efforts to get the university to publicly repudiate the false charges brought against him when he was a student leader in 1973—and that led to his expulsion from the career he had chosen. A day later, I pass by a house where my wife and I had a delicious dinner prepared by Brazilian refugees sometime in 1972—and that after the coup was taken over by the secret police and turned into a torture center. And on and on and on it goes.

One would have hoped that this milestone, half a century after the whirlwind devastation of our democracy, might have provided some relief from these lacerations, some agreement among Chileans of all persuasions, not only to lament the shocking abuses of the military regime but also to resolutely condemn the coup itself. No such concord has been forthcoming in a land more polarized than ever. Indeed, recent extensive electoral victories suggest that José Antonio Kast, an outspoken Pinochet enthusiast, might well be Chile’s next president. Kast, along with many ultraconservatives, justifies the coup as having been the only way to save the country from chaos and communism. According to a current poll, 36 percent of Chileans believe that Pinochet was right to overthrow Allende.

It is clear, then, that the battle for memory and interpretation that fiercely commenced the very day of the coup—when some Chileans celebrated and drank champagne while their compatriots were being forced to gag on their own piss in some dank cellar—will continue unabated into the near and perhaps the far future.

And yet, 80 percent of Chileans alive today have no experience of the coup or the Allende years. When they remember the military takeover, what image will prevail?

I wager it will be the iconic photo of La Moneda burning, with huge billows of smoke emerging from the besieged building. Perhaps the majority will see that picture as a warning that democracy is precarious and can be slowly undermined and then, one day, destroyed, even in countries with long traditions of adherence to the rule of law—a warning that other nations across the world should heed and meditate upon.

Is that, then, how September 11, 1973, will ultimately be remembered, as a day when our attempt at national liberation was reduced to rubble, a day overwhelmed by desolation and anguish? Is that the best way to remember what the coup wrought, dwelling on an endless dirge of grief, bleeding outrages into the present?

Or will some other memory persist?

Because inside that Presidential Palace in flames, a man is awaiting death. Allende must know that he will pay with his life for the catastrophe into which he has led his people. But that is not the message he sends to the world in his final hours. Not a word about his personal failings or remorse. What matters, in this moment that defines him and his legacy forever, is his decision not to surrender to the usurpers but to resist to the end.

Others “will overcome,” he says, “this gray and bitter moment when treason tries to impose itself.” He is passing the torch of struggle and solidarity, stating his certainty that the dream of a just society will not die with him. That president whom I loved like a father affirms his faith in Chile and its destiny. Tengo fe en Chile y su destino. And, then, his farewell: “These are my last words and I am certain that my sacrifice will not be in vain.”

It is my hope that enough people in Chile now and more than enough for generations to come will listen, that this is what they will remember, along with the rest of the world, about that day when Allende and democracy died in my damaged land.

More from The Nation

Exclusive: With My Father, Salvador Allende, in His Final Hours Exclusive: With My Father, Salvador Allende, in His Final Hours

An excerpt from 11 de Septiembre: Esa semana (11th of September: That Week)

Chile: The Secrets the US Government Continues to Hide Chile: The Secrets the US Government Continues to Hide

Fifty years after the military coup that brought down Salvador Allende and installed the Pinochet dicatorship, there are still top secret documents on the US role that must be dec...

Kissinger’s Bloody Paper Trail in Chile Kissinger’s Bloody Paper Trail in Chile

The secret memo in which he plotted the murder of Chilean democracy.

Chile’s Battle for Memory: A Report From the Latest Front Chile’s Battle for Memory: A Report From the Latest Front

The fight over a memorial to my friend Carlos Berger and other victims of the Caravan of Death reveals that there are still many in Chile who resist the lessons of our country’s tr...

Stumbling on Chilean Stones—and Chilean History Stumbling on Chilean Stones—and Chilean History

Chile has a new leader and a bright future. But a country in which 44 percent of the electorate voted for an admirer of Pinochet is in need of as many obstacles to forgetting as po...

Chile’s “New Left” Brings Hope Chile’s “New Left” Brings Hope

With capital already taking flight and the rise of the far right, Gabriel Boric’s administration isn’t in for an easy ride.